Roman Catholicism in Scotland

Roman Catholicism in Scotland (Scottish Gaelic: An Eaglais Chaitligeach), overseen by the Scottish Bishops' Conference, is part of the worldwide Roman Catholic church, the Christian church headed by the Pope. After being firmly established in Scotland for nearly a millennium, Roman Catholicism was outlawed following the Scottish Reformation in 1560. Catholic Emancipation in 1793 helped Roman Catholics regain civil rights. In 1878, the Roman Catholic hierarchy was formally restored.[1] Throughout these changes, several pockets in Scotland retained a significant pre-Reformation Roman Catholic population, including parts of Banffshire, the Hebrides, and more northern parts of the Scottish Highlands.

In 1716, Scalan seminary was established in the Highlands and rebuilt in the 1760s by Bishop John Geddes, a well-known figure in the Edinburgh of the Enlightenment period. When Robert Burns wrote to a correspondent that "the first [that is, finest] cleric character I ever saw was a Roman Catholick," he was referring to Bishop Geddes.[2] Scottish Gaeldom has been both Roman Catholic and Protestant in modern times. A number of Scottish Gaelic areas now are mainly Roman Catholic, including Barra, South Uist, and Moidart. The poet and novelist Angus Peter Campbell writes frequently about Roman Catholicism in his work. (See also the "Religion of the Yellow Stick".)

In the 2011 census, 16% of the population of Scotland described themselves as being Roman Catholic, compared with 32% affiliated with the Church of Scotland.[3] Many Roman Catholics in Scotland are the descendants of Irish immigrants and of Highland migrants who moved to Scotland's cities and towns during the 19th century, when there was a potato famine in Ireland, and older Scottish Highland minorities. However, there are significant numbers of Italian, Lithuanian[4] and Polish descent, with more recent Polish immigrants again boosting the numbers of continental Roman Catholic Europeans in Scotland. Owing to immigration (overwhelmingly white European), it is estimated that, in 2009, there were about 850,000 Catholics in a country of 5.1 million.[5] Between 1994 and 2002, Roman Catholic attendance in Scotland declined 19% to just over 200,000.[6] By 2008, the Roman Catholic Bishops' Conference of Scotland estimated that 184,283 attended Mass regularly.[7]

History

Establishment

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now lowland Scotland from Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of Britannia.[8] It is presumed to have survived among the Brythonic enclaves in the south of modern Scotland, but retreated as the pagan Anglo-Saxons advanced.[9] Scotland was largely converted by Irish-Scots missions associated with figures such as St Columba from the fifth to the seventh centuries. These missions tended to found monastic institutions and collegiate churches that served large areas.[10] Partly as a result of these factors, some scholars have identified a distinctive form of Celtic Christianity, in which abbots were more significant than bishops, attitudes to clerical celibacy were more relaxed and there was some significant differences in practice with Roman Christianity, particularly the form of tonsure and the method of calculating Easter, although most of these issues had been resolved by the mid-seventh century.[11][12] After the reconversion of Scandinavian Scotland from the tenth century, Christianity under papal authority was the dominant religion of the kingdom.[13]

Medieval Catholicism

In the Norman period the Scottish church underwent a series of reforms and transformations. With royal and lay patronage, a clearer parochial structure based around local churches was developed.[14] Large numbers of new foundations, which followed continental forms of reformed monasticism, began to predominate and the Scottish church established its independence from England, developed a clearer diocesan structure, becoming a "special daughter of the see of Rome", but lacking leadership in the form of archbishops.[15] In the Late Middle Ages the problems of schism in the Catholic Church allowed the Scottish Crown to gain greater influence over senior appointments and two archbishoprics had been established by the end of the fifteenth century.[16] While some historians have discerned a decline of monasticism in the Late Middle Ages, the mendicant orders of friars grew, particularly in the expanding burghs, to meet the spiritual needs of the population. New saints and cults of devotion also proliferated. Despite problems over the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death in the fourteenth century, and some evidence of heresy in this period, the church in Scotland remained relatively stable before the Reformation in the sixteenth century.[16]

Scottish Reformation

That remained the case until the Scottish Reformation in the mid-16th century, when the Church in Scotland broke with the papacy and adopted a Calvinist confession in 1560. At that point, the celebration of the Roman Catholic mass was outlawed.[17] Although officially illegal, Roman Catholicism survived in parts of Scotland. The hierarchy of the Church played a relatively small role and the initiative was left to lay leaders. Where nobles or local lairds offered protection it continued to thrive, as with Clanranald on South Uist, or in the north-east where the Earl of Huntly was the most important figure. In these areas Catholic sacraments and practices were maintained with relative openness.[18] Members of the nobility were probably reluctant to pursue each other over matters of religion because of strong personal and social ties. An English report in 1600 suggested that a third of nobles and gentry were still Catholic in inclination.[19] In most of Scotland, Catholicism became an underground faith in private households, connected by ties of kinship. This reliance on the household meant that women often became important as the upholders and transmitters of the faith, such as in the case of Lady Fernihurst in the Borders. They transformed their households into centres of religious activity and offered places of safety for priests.[18]

Because the reformed kirk took over the existing structures and assets of the Church, any attempted recovery by the Catholic hierarchy was extremely difficult. After the collapse of Mary's cause in the civil wars in the 1570s, and any hope of a national restoration of the old faith, the hierarchy began to treat Scotland as a mission area. The leading order of the Counter-reformation, the newly founded Jesuits, initially took relatively little interest in Scotland as a target of missionary work. Their effectiveness was limited by rivalries between different orders at Rome. The initiative was taken by a small group of Scots connected with the Crichton family, who had supplied the bishops of Dunkeld. They joined the Jesuit order and returned to attempt conversions. Their focus was mainly on the court, which led them to into involvement in a series of complex political plots and entanglements. The majority of surviving Scottish lay followers were largely ignored.[18] Some were to convert to Roman Catholicism, as did John Ogilvie (1569–1615), who went on to be ordained a priest in 1610, later being hanged for proselytism in Glasgow and often thought of as the only Scottish Catholic martyr of the Reformation era.[20] Nevertheless, Roman Catholicism's illegal status had a devastating impact on The Church's fortunes, although a significant congregation did continue to adhere, especially in the more remote Gaelic-speaking areas of the Highlands and Islands.[21]

Decline from the 17th century

Numbers probably reduced in the seventeenth century and organisation deteriorated.[22] The aftermath of the failed Jacobite risings in 1715 and 1745 further damaged the Roman Catholic cause in Scotland.[22]

The Pope appointed Thomas Nicolson as the first Vicar Apostolic over the mission in 1694.[23] The country was organised into districts and by 1703 there were thirty-three Catholic clergy.[24] In 1733 it was divided into two vicariates, one for the Highland and one for the Lowland, each under a bishop. A Roman Catholic seminary in Scalan in Glenlivet was the preliminary centre of education for Catholic priests in the area. It was illegal, and it was burned to the ground on several occasions by soldiers sent from beyond The Highlands.[25] Beyond Scalan there were six attempts to found a seminary in the Highlands between 1732 and 1838, all suffering financially under Catholicism's illegal status.[23] Clergy entered the country secretly and although services were illegal they were maintained.[24]

Exact numbers of communicants are uncertain, given the illegal status of Catholicism. In 1755 it was estimated that there were some 16,500 communicants, mainly in the north and west.[24] In 1764, "the total Catholic population in Scotland would have been about 33,000 or 2.6% of the total population. Of these 23,000 were in the Highlands".[26] Another estimate for 1764 is of 13,166 Catholics in the Highlands, perhaps a quarter of whom had emigrated by 1790,[27] and another source estimates Roman Catholics as perhaps 10% of the population.[27]

Impact of the Clearances

While the landlords responsible for the Highland Clearances did not target people for ethnic or religious reasons,[28] there is evidence of anti-Catholicism in the thoughts of some who were responsible for the clearances.[29][30][31][32][33][34][35] In particular, large numbers of Catholics emigrated from the Western Highlands in the period 1770 to 1810 and there is evidence that anti Catholic sentiment (along with famine, poverty and rising rents) was a contributory factor in that period.[36][37] Noteworthy figures in the late stages of the specifically Catholic clearances and emigration from Scotland include Bishop Alexander Macdonnell, who, against the odds, made possible a settlement in Ontario, Canada, of an army regiment, and their families, after its disbandment.[38][39]

Large-scale Catholic immigration

During the 19th century, Irish immigration substantially increased the number of Roman Catholics in the country, especially in the West of Scotland. Later Italian, Polish, and Lithuanian immigrants reinforced those numbers.

The Roman Catholic hierarchy was re-established in 1878, at the beginning of his pontificate, by Pope Leo XIII. As of late 2013, Archbishop Leo Cushley held the senior Roman Catholic bishopric in Scotland – that of Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh – following the resignation of Cardinal Keith O'Brien.

Sectarian tensions

Mass immigration saw the emergence of sectarian tensions. In 1923, the Church of Scotland produced a highly controversial (and since repudiated) report, entitled The Menace of the Irish Race to our Scottish Nationality, accusing the largely immigrant Roman Catholic population of subverting Presbyterian values and of causing drunkenness, crime and financial imprudence. John White, one of the leading figures in the Church of Scotland at the time, called for a "racially pure" Scotland, declaring "Today there is a movement throughout the world towards the rejection of non-native constituents and the crystallization of national life from native elements."[40]

Such officially hostile attitudes started to wane considerably from the 1930s and '40s onward, especially when the established church leaders learned of what was happening in eugenics-conscious Nazi Germany and of the dangers of a national or folk-church. Germans who were ethnically Slavic or Jewish were not considered "true" Germans or members of the German Volk.[41][42]

Denominational concord, social change and ongoing communal divisions

In 1986, the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland expressly repudiated the sections of the Westminster Confession directly attacking Roman Catholicism.[43] In 1990, both the Church of Scotland and the Roman Catholic Church were founder members of the ecumenical bodies Churches Together in Britain and Ireland and Action of Churches Together in Scotland; relations between denominational leaders are now very cordial. Unlike the relationship between the hierarchies of the different churches, however, some communal tensions remain.

The association between football and displays of sectarian behaviour by some fans has been a source of embarrassment and concern to the management of certain clubs. The bitter rivalry between Celtic and Rangers in Glasgow, known as the Old Firm, is known worldwide for its sectarian divide. Celtic was founded by Irish Catholic immigrants and Rangers is traditionally supported by Unionists and Protestants. Sectarian tensions can still be very real, though perhaps diminished compared with past decades. Perhaps the greatest psychological breakthrough was when Rangers signed Mo Johnston (a Roman Catholic) in 1989. Celtic, on the other hand have never had a policy of not signing players due to their religion, and some of the club's greatest figures have been Protestants.[44][45]

From the 1980s the UK government passed several acts that had provision concerning sectarian violence. These included the Public Order Act 1986, which introduced offences relating to the incitement of racial hatred, and the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, which introduced offences of pursuing a racially aggravated course of conduct that amounts to harassment of a person. The 1998 Act also requiring courts to take into account where offences are racially motivated, when determining sentence. In the twenty-first century the Scottish Parliament legislated against sectarianism. This included provision for religiously aggravated offences in the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003. The Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 strengthened statutory aggravations for racial and religiously motivated crimes. The Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012, criminalised behaviour which is threatening, hateful or otherwise offensive at a regulated football match including offensive singing or chanting. It also criminalised the communication of threats of serious violence and threats intended to incite religious hatred.[46]

The Roman Catholic community in Scotland was once largely working-class. In recent years, the situation has changed markedly: many Roman Catholics can be found in what were called the professions, and it is now unremarkable for Roman Catholics to be occupying posts in the judiciary or in national politics. In 1999. the Rt Hon Dr John Reid MP became the first Roman Catholic to hold the office of Secretary of State for Scotland. His succession by the Rt Hon Helen Liddell MP in 2001 attracted considerably more media comment that she was the first woman to hold the post than that she was the second Roman Catholic. Also notable was the recent appointment of Louise Richardson to the University of St. Andrews as its Principal and Vice-Chancellor. St. Andrews is the third oldest university of the English-speaking world. Richardson, a Roman Catholic, was born in Ireland and is a naturalised United States citizen. She is the first woman to hold that office and first Roman Catholic to hold it since the Reformation.[47]

It is notable that the Roman Catholic church recognises the separate identities of Scotland and of England and Wales. The denomination in Scotland is thus governed by its own hierarchy and Bishops' Conference, not under the control of English bishops. In recent years, for example, there have been times when it was especially the Scottish Roman Catholic bishops who took the floor in the United Kingdom to argue for Roman Catholic social and moral teaching. Interestingly, the presidents of the Bishops' Conferences of England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland do meet formally to discuss "mutual concerns", though they are separate national entities. "Closer cooperation between the presidents can only help the Church's work", a spokesman noted recently.[48]

Organisation

There are two Roman Catholic archbishops and six bishops in Scotland:

Furthermore, the UK troops in Scotland are pastorally served by the Military Ordinariate for Great-Britain and the Ukrainian catholics (Byzantine Rite) by the Ukrainian Catholic Diocese of the Holy Family of London, both shared with England and Wales and exempt, i.e. directly subject to the Hole See.

Recent years

Since 1982 the proportion of Scottish Catholics dropped 18%, baptisms dropped 39% and Catholic church marriages dropped 63%. The number of priests also dropped.[49] Between the 2001 Census and the 2011 Census the proportion of Catholics remained steady while that of other Christians, notably the Church of Scotland dropped.[50][51][52]

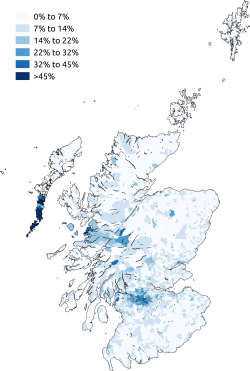

In 2001, Catholics were a minority in each of Scotland's 32 council areas but in a few parts of the country their numbers rivalled those of the official Church of Scotland. The most Catholic part of the country is composed of the western Central Belt council areas near Glasgow. In Inverclyde, 38.3% of persons responding to the 2001 Scottish Census reported themselves to be Catholic compared to 40.9% as adherents of the Church of Scotland. North Lanarkshire also already had a large Catholic minority at 36.8% compared to 40.0% in the Church of Scotland. Following in order were West Dunbartonshire (35.8%), Glasgow City (31.7%), Renfrewshire (24.6%), East Dunbartonshire (23.6%), South Lanarkshire (23.6%) and East Renfrewshire (21.7%).

In 2011, Catholics outnumbered adherents of the Church of Scotland in several council areas, including North Lanarkshire, Inverclyde, West Dunbartonshire and the most populous one: Glasgow City.[53] Between the two censuses, numbers in Glasgow with no religion rose significantly while those noting their affiliation to the Church of Scotland dropped significantly so that the latter fell below that with an affiliation to Roman Catholicism.[54]

At a smaller geographic scale, one finds that the two most Catholic parts of Scotland are: (1) the southern-most islands of the Western Isles, especially Barra and South Uist, populated by Gaelic-speaking Scots of long-standing; and (2) the eastern suburbs of Glasgow, especially around Coatbridge, populated mostly by the descendants of Irish immigrants.[55]

According to the 2011 census, Catholics comprise 16% of the overall population, making it the second largest church after the Church of Scotland (32%).[56]

In recent years the Catholic Church in Scotland has suffered from poor publicity connected to attacks made against secular and liberal values by senior clergy. Joseph Devine, Bishop of Motherwell, came under fire after describing the "gay lobby" as "the opposition" who were responsible for mounting "a giant conspiracy" to shape public policy.[57] Criticism has also been levelled at perceived intransigence on joint faith schools over threats to withdraw acqueisence if guarantees of separate staff rooms, toilets, gyms, visitor and pupil entrances were not met.[58] In 2003 a Catholic church spokesman branded sex education as "pornography" and Cardinal O'Brien claimed plans to give sex education to pre-school children amounted to "state-sponsored sexual abuse of minors."[59]

Roughly half of Catholic parishes in west Scotland may close because of a priest shortage and over half are closing in the Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh.[60][61]

In early 2013, Scotland's most senior cleric, Cardinal Keith O'Brien resigned after allegations of sexual misconduct were made against him and partially admitted.[62] Subsequently, allegations were made that several other cases of alleged sexual misconduct took place involving other priests.[63]

Catholic sexual abuse cases in Europe have included Scotland and the standing of the Church has been damaged.

See also

- Bishops' Conference of Scotland

- Catholic Church by country

- Catholic Church hierarchy

- Catholic Church in England and Wales

- Lists of patriarchs, archbishops, and bishops

- Catholicism in the Western Isles

- Roman Catholic Church in Ireland

- Roman Catholicism in the United Kingdom

- Scottish Catholic Observer

References

- ↑ Archdiocese of Edinburgh www.archdiocese-edinburgh.com. Retrieved 21 February 2009

- ↑ Michael Martin, "Sae let the Lord be thankit," The Tablet, 27 June 2009, 20.

- ↑ "Census reveals huge rise in number of non-religious Scots (From Herald Scotland)". Heraldscotland.com. 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ↑ "Legacies – Immigration and Emigration – Scotland – Strathclyde – Lithuanians in Lanarkshire". BBC. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ Andrew Collier "Scotland's confident Catholics" Tablet 10 January 2009, 16

- ↑ Tad Turski (1 February 2011). "Statistics". Dioceseofaberdeen.org. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "How many Catholics are there in Britain?". BBC News. 15 September 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ B. Cunliffe, The Ancient Celts (Oxford, 1997), ISBN 0-14-025422-6, p. 184.

- ↑ O. Davies, Celtic Spirituality (Paulist Press, 1999), ISBN 0-8091-3894-8, p. 21.

- ↑ O. Clancy, "The Scottish provenance of the 'Nennian' recension of Historia Brittonum and the Lebor Bretnach " in: S. Taylor (ed.), Picts, Kings, Saints and Chronicles: A Festschrift for Marjorie O. Anderson (Dublin: Four Courts, 2000), pp. 95–6 and A. P. Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0100-7, pp. 82–3.

- ↑ C. Evans, "The Celtic Church in Anglo-Saxon times", in J. D. Woods, D. A. E. Pelteret, The Anglo-Saxons, synthesis and achievement (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1985), ISBN 0-88920-166-8, pp. 77–89.

- ↑ C. Corning, The Celtic and Roman Traditions: Conflict and Consensus in the Early Medieval Church (Macmillan, 2006), ISBN 1-4039-7299-0.

- ↑ A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 67–8.

- ↑ A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 109–117.

- ↑ P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1-84384-096-0, pp. 26–9.

- 1 2 J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 76–87.

- ↑ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 120–1.

- 1 2 3 J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1455-9, pp. 232.

- ↑ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, p. 133.

- ↑ James Buckley, Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt, Trent Pomplun, eds, The Blackwell Companion to Catholicism (London: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), ISBN 1444337327, p. 164.

- ↑ John Prebble, Culloden (Pimlico: London, 1961), p. 50.

- 1 2 J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5 (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 416–7.

- 1 2 M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, p. 365.

- 1 2 3 J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 298–9.

- ↑ J. Prebble, (1961) Culloden (London: Pimlico, 1963), p. 50.

- ↑ Toomey, Kathleen (1991) Emigration from the Scottish Catholic bounds 1770–1810 and the role of the clergy, PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, http://hdl.handle.net/1842/6795, Chapter 1.

- 1 2 Lynch, Michael,Scotland, A New History (Pimlico: London, 1992), p. 367.

- ↑ G. Dawson and S. Farber, Forcible Displacement Throughout the Ages: Towards an International Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Forcible Displacement (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2012), ISBN 9004220542, p. 31.

- ↑ Prebble, John (1961) Culloden, Pimlico, London pp. 49–51, 325–326.

- ↑ "Appreciation: John Prebble'". The Guardian. 9 February 2001. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ↑ "The Cultural Impact of the Highland Clearances". Noble, Ross BBC History. 7 July 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ↑ "Toiling in the Vale of Tears: Everyday life and Resistance in South Uist, Outer Hebrides, 1760–1860". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. June 1999. JSTOR 20852924

- ↑ Prebble, John (1969) The Highland Clearances, Penguin, London p. 137.

- ↑ Kelly, Bernard William (1905) The Fate of Glengarry: or, The Expatriation of the Macdonells, an historico-biographical study, James Duffy & Co. Ltd, Dublin pp. 6–11, 18–31, 43–45.

- ↑ Rea, J.E. (1974) Bishop Alexander MacDonell and The Politics of Upper Canada, Ontario Historical Society, Toronto pp. 2–7, 9–10.

- ↑ Richards, Eric (2008). "Chapter 4, Section VI: Emigration". The Highland Clearances: People, Landlords and Rural Turmoil. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. p. 81.

- ↑ Toomey, Kathleen (1991) Emigration from the Scottish Catholic bounds 1770–1810 and the role of the clergy, PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

- ↑ Kelly, Bernard William (1905) The Fate of Glengarry: or, The Expatriation of the Macdonells, an historico-biographical study, James Duffy & Co. Ltd, Dublin

- ↑ Rea, J.E. (1974) Bishop Alexander MacDonell and The Politics of Upper Canada, Ontario Historical Society, Toronto

- ↑ Duncan B. Forrester "Ecclesia Scoticana – Established, Free, or National?" Theology March/April 1999, 80–89

- ↑ Kevin Spicer Nazi Priests (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, published in association with Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington [D.C.], 2008), 12–28, 74–75,95–6,114–24,164–68,175–6,182–92,202,231

- ↑ Kevin Spicer Resisting the Third Reich (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2004), 139, 149, 175–8.

- ↑ E. Kelly, "Challenging Sectarianism in Scotland: The Prism of Racism", Scottish Affairs Vol 42 (First Series), Issue 1, 2003, pp. 32–56, ISSN 0966-0356.

- ↑ "Celtic Football Club". Celticfc.net. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ↑ "Celtic Football Club". Celticfc.net. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ↑ "Action to tackle hate crime and sectarianism", The Scottish Government, retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Bonner "In Scotland, New Leadership Crumbles Old Barrier" The New York Times 28 March 2009, 5.

- ↑ "Groundbreaking meeting for presidents," The Tablet, 13 June 2009, 38.

- ↑ Strength of the Catholic Church in Scotland

- ↑ Religious Gruops Demographics

- ↑ Census reveals huge rise in number of non-religious scots

- ↑ number of scottish catholics on the rise

- ↑ Religion by council area, Scotland, 2011

- ↑ Table 2 Changes in religion in Glasgow between 2001 and 2011

- ↑ Scotland's Census Results On-Line (SCROL)

- ↑ "Census reveals huge rise in number of non-religious Scots," Brian Donnelly, Herald Scotland, 13 September 2013

- ↑ "Catholic bishop hits out at 'gay conspiracy' to destroy Christianity – News". The Scotsman (Edinburgh). 12 March 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Bishop rejects plans for seven new joint-campus mixed-faith schools – Education". The Scotsman (Edinburgh). 23 July 2004. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Church labels sex education 'pornography' – Education". The Scotsman (Edinburgh). 23 September 2004. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ Archbishop urges faithful to resist pessimism ahead of parish closures

- ↑ Time for good deeds from the dying Catholic church

- ↑ Pigott, Robert (2013-02-25). "BBC News – Cardinal Keith O'Brien resigns as Archbishop". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ↑ Catherine Deveney (7 April 2013). "Catholic priests unmasked: 'God doesn't like boys who cry' | World news | The Observer". London: Guardian. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

External links

- Bishops' Conference of Scotland

- Facts about Catholics in Scotland

- Catholic Encyclopedia's article on Scotland

- Scottish Catholic Observer

- National Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE (selection of archive films relating to Roman Catholicism in Scotland)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||