Robust measures of scale

In statistics, a robust measure of scale is a robust statistic that quantifies the statistical dispersion in a set of numerical data. The most common such statistics are the interquartile range (IQR) and the median absolute deviation (MAD). These are contrasted with conventional measures of scale, such as sample variance or sample standard deviation, which are non-robust, meaning greatly influenced by outliers.

These robust statistics are particularly used as estimators of a scale parameter, and have the advantages of both robustness and superior efficiency on contaminated data, at the cost of inferior efficiency on clean data from distributions such as the normal distribution. To illustrate robustness, the standard deviation can be made arbitrarily large by increasing exactly one observation (it has a breakdown point of 0, as it can be contaminated by a single point), a defect that is not shared by robust statistics.

IQR and MAD

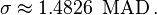

The most familiar robust measures of scale are the interquartile range (IQR) and the median absolute deviation (MAD). The IQR is the difference between the 75th percentile and the 25th percentile of a sample; this is the 25% trimmed range, an example of an L-estimator. Other trimmed ranges, such as the interdecile range (10% trimmed range) can also be used. The MAD is the median of the absolute values of the differences between the data values and the overall median of the data set; for a Gaussian distribution, MAD is related to σ as  (The derivation can be found here.)

(The derivation can be found here.)

Estimation

Robust measures of scale can be used as estimators of properties of the population, either for parameter estimation or as estimators of their own expected value.

For example, robust estimators of scale are used to estimate the population variance or population standard deviation, generally by multiplying by a scale factor to make it an unbiased consistent estimator; see scale parameter: estimation. For example, dividing the IQR by 2√2 erf−1(1/2) (approximately 1.349), makes it an unbiased, consistent estimator for the population variance if the data follow a normal distribution.

In other situations, it makes more sense to think of a robust measure of scale as an estimator of its own expected value, interpreted as an alternative to the population variance or standard deviation as a measure of scale. For example, the MAD of a sample from a standard Cauchy distribution is an estimator of the population MAD, which in this case is 1, whereas the population variance does not exist.

Efficiency

These robust estimators typically have inferior statistical efficiency compared to conventional estimators for data drawn from a distribution without outliers (such as a normal distribution), but have superior efficiency for data drawn from a mixture distribution or from a heavy-tailed distribution, for which non-robust measures such as the standard deviation should not be used.

For example, for data drawn from the normal distribution, the MAD is 37% as efficient as the sample standard deviation, while the Rousseeuw–Croux estimator Qn is 88% as efficient as the sample standard deviation.

Absolute pairwise differences

Rousseeuw and Croux[1] propose alternatives to the MAD, motivated by two weaknesses of it:

- It is inefficient (37% efficiency) at Gaussian distributions.

- it computes a symmetric statistic about a location estimate, thus not dealing with skewness.

They propose two alternative statistics based on pairwise differences: Sn and Qn, defined as:

where  is a constant depending on

is a constant depending on  .

.

These can be computed in O(n log n) time and O(n) space.

Neither of these requires location estimation, as they are based only on differences between values. They are both more efficient than the MAD under a Gaussian distribution: Sn is 58% efficient, while Qn is 82% efficient.

For a sample from a normal distribution, Sn is approximately unbiased for the population standard deviation even down to very modest sample sizes (<1% bias for n = 10). For a large sample from a normal distribution, 2.219144465985075864722Qn is approximately unbiased for the population standard deviation. For small or moderate samples, the expected value of Qn under a normal distribution depends markedly on the sample size, so finite-sample correction factors (obtained from a table or from simulations) are used to calibrate the scale of Qn.

The biweight midvariance

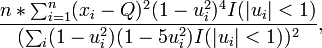

Like Sn and Qn, the biweight midvariance aims to be robust without sacrificing too much efficiency. It is defined as

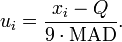

where I is the indicator function, Q is the sample median of the Xi, and

Its square root is a robust estimator of scale, since data points are downweighted as their distance from the median increases, with points more than 9 MAD units from the median having no influence at all.

Simultaneous estimation of location and scale

Mizera & Müller (2004) propose a robust depth-based estimator for location and scale simultaneously.[2]

References

- ↑ Rousseeuw, Peter J.; Croux, Christophe (December 1993), "Alternatives to the Median Absolute Deviation", Journal of the American Statistical Association (American Statistical Association) 88 (424): 1273–1283, doi:10.2307/2291267, JSTOR 2291267

- ↑ Mizera, I.; Müller, C. H. (2004), "Location-scale depth", Journal of the American Statistical Association 99 (468): 949–966, doi:10.1198/016214504000001312.