Robert McNamara

| Robert McNamara | |

|---|---|

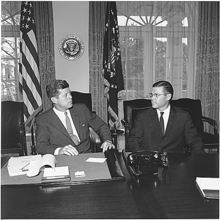

Official portrait photograph (1961) | |

| 8th United States Secretary of Defense | |

|

In office January 21, 1961 – February 29, 1968 | |

| President | |

| Deputy | |

| Preceded by | Thomas S. Gates Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Clark M. Clifford |

| 5th President of the World Bank Group | |

|

In office April 1968 – June 1981 | |

| Preceded by | George David Woods |

| Succeeded by | Alden W. Clausen |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Robert Strange McNamara June 9, 1916 San Francisco, California |

| Died |

July 6, 2009 (aged 93) Washington, D.C. |

| Resting place |

Arlington National Cemetery Arlington, Virginia |

| Political party | Republican[1][2] |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

Robert Craig McNamara Kathleen McNamara Spears Margaret Elizabeth Pastor (née McNamara) |

| Alma mater |

UC Berkeley (BA) Harvard Business School (MBA) |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

| Awards | |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Service/branch | U.S. Army Air Forces |

| Years of service | 1940–46 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

|

| |

Robert Strange McNamara (June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, during which time he played a major role in escalating the United States involvement in the Vietnam War.[4] Following that, he served as President of the World Bank from 1968 to 1981. McNamara was responsible for the institution of systems analysis in public policy, which developed into the discipline known today as policy analysis.[5] McNamara consolidated intelligence and logistics functions of the Pentagon into two centralized agencies: the Defense Intelligence Agency and the Defense Supply Agency.

Prior to his public service, McNamara was one of the "Whiz Kids" who helped rebuild Ford Motor Company after World War II and briefly served as Ford's President before becoming Secretary of Defense. A group of advisors he brought to the Pentagon inherited the "Whiz Kids" moniker.

McNamara remains the longest serving Secretary of Defense, having remained in office over seven years.

Early life and career

Robert McNamara was born in San Francisco, California.[3] His father was Robert James McNamara, sales manager of a wholesale shoe company, and his mother was Clara Nell (Strange) McNamara.[6][7] His father's family was Irish and in about 1850, following the Great Irish Famine, had emigrated to the U.S., first to Massachusetts and later to California.[8] He graduated from Piedmont High School in Piedmont in 1933, where he was president of the Rigma Lions boys club[9] and earned the rank of Eagle Scout. McNamara attended the University of California in Berkeley and graduated in 1937 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics with minors in mathematics and philosophy. He was a member of Phi Gamma Delta fraternity,[10] was elected to Phi Beta Kappa his sophomore year, and earned a varsity letter in crew. McNamara was also a member of the UC Berkeley's Order of the Golden Bear which was a fellowship of students and leading faculty members formed to promote leadership within the student body. He then attended Harvard Business School and earned an MBA in 1939.

After business school, McNamara worked a year for the accounting firm Price Waterhouse in San Francisco, then returned to Harvard in August 1940 to teach accounting in the business school and became the highest paid and youngest assistant professor at that time. Following his involvement there in a program to teach analytical approaches used in business to officers of the United States Army Air Forces, he entered the USAAF as a captain in early 1943, serving most of World War II with its Office of Statistical Control. One major responsibility was the analysis of U.S. bombers' efficiency and effectiveness, especially the B-29 forces commanded by Major General Curtis LeMay in India, China, and the Mariana Islands.[11] McNamara established a statistical control unit for XX Bomber Command and devised schedules for B-29s doubling as transports for carrying fuel and cargo over The Hump. He left active duty in 1946 with the rank of lieutenant colonel and with a Legion of Merit.

President of Ford Motor Company

In 1946, Charles "Tex" Thornton, a colonel under whom McNamara had served, put together a group of officers from his AAF Statistical Control operation to go into business together. Thornton had seen an article in Life magazine portraying Ford as being in dire need of reform. Henry Ford II, himself a World War II veteran from the Navy, hired the entire group of 10, including McNamara.

The "Whiz Kids", as they came to be known, helped the money-losing company reform its chaotic administration through modern planning, organization and management control systems. Whiz Kids origins: Because of their youth, combined with asking lots of questions, Ford employees initially and disparagingly, referred to them as the "Quiz Kids". In a remarkable "turning of the tables", these Quiz Kids rebranded themselves as the "Whiz Kids" and backed-up their new moniker with performance driven results. Starting as manager of planning and financial analysis, he advanced rapidly through a series of top-level management positions.

McNamara was a force behind the wildly popular Ford Falcon sedan, introduced in the fall of 1959—a small, simple and inexpensive-to-produce counter to the large, expensive vehicles prominent in the late 1950s. McNamara placed a high emphasis on safety: the Lifeguard options package introduced the seat belt (a novelty at the time) and a dished steering wheel which helped to prevent the driver from being impaled on the steering column.[12]

After the Lincoln line's very large 1958, 1959, and 1960 models proved unpopular, McNamara pushed for smaller versions, such as the 1961 Lincoln Continental — now an icon among 1960s automobiles.

On November 9, 1960, McNamara became the first president of Ford Motor Company from outside the Ford family. He received credit for the company's postwar success.

Secretary of Defense

After his election in 1960, President-elect John F. Kennedy first offered the post of Secretary of Defense to former secretary Robert A. Lovett; Lovett declined but recommended McNamara. Kennedy then sent Sargent Shriver to approach him regarding either the Treasury or the Defense cabinet post less than five weeks after McNamara had become president at Ford. McNamara immediately rejected the Treasury position but eventually accepted Kennedy's invitation to serve as Secretary of Defense.

According to Special Counsel Ted Sorensen, Kennedy regarded McNamara as the "star of his team, calling upon him for advice on a wide range of issues beyond national security, including business and economic matters."[13] McNamara became one of the few members of the Kennedy Administration to work and socialize with Kennedy, and he became so close to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy that he served as a pallbearer at the younger Kennedy's funeral in 1968.[14] McNamara's specialty was to statistically analyze the efficiency of fighting the protracted Vietnam War, including how to maximize the use of defoliants, bombs, and cannon.[15]

Initially, the basic policies outlined by President Kennedy in a message to Congress on March 28, 1961, guided McNamara in the reorientation of the defense program. Kennedy rejected the concept of first-strike attack and emphasized the need for adequate strategic arms and defense to deter nuclear attack on the United States and its allies. U.S. arms, he maintained, must constantly be under civilian command and control, and the nation's defense posture had to be "designed to reduce the danger of irrational or unpremeditated general war". The primary mission of U.S. overseas forces, in cooperation with allies, was "to prevent the steady erosion of the Free World through limited wars". Kennedy and McNamara rejected massive retaliation for a posture of flexible response. The U.S. wanted choices in an emergency other than "inglorious retreat or unlimited retaliation", as the president put it. Out of a major review of the military challenges confronting the U.S. initiated by McNamara in 1961 came a decision to increase the nation's "limited warfare" capabilities. These moves were significant because McNamara was abandoning President Dwight D. Eisenhower's policy of massive retaliation in favor of a flexible response strategy that relied on increased U.S. capacity to conduct limited, non-nuclear warfare.

The Kennedy administration placed particular emphasis on improving ability to counter communist "wars of national liberation", in which the enemy avoided head-on military confrontation and resorted to political subversion and guerrilla tactics. As McNamara said in his 1962 annual report, "The military tactics are those of the sniper, the ambush, and the raid. The political tactics are terror, extortion, and assassination." In practical terms, this meant training and equipping U.S. military personnel, as well as such allies as South Vietnam, for counterinsurgency operations.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, McNamara served as a member of EXCOMM and played a large role in the Administration's handling and eventual defusing of the Cuban Missile Crisis. He was a strong proponent of the blockade option over a missile strike and helped persuade the Joint Chiefs of Staff to agree with the blockade option.

Increased attention to conventional strength complemented these special forces preparations. In this instance he called up reserves and also proceeded to expand the regular armed forces. Whereas active duty strength had declined from approximately 3,555,000 to 2,483,000 between 1953 (the end of the Korean War) and 1961, it increased to nearly 2,808,000 by June 30, 1962. Then the forces leveled off at around 2,700,000 until the Vietnam military buildup began in 1965, reaching a peak of nearly 3,550,000 by mid-1968, just after McNamara left office.[16]

Other steps

McNamara took other steps to increase U.S. deterrence posture and military capabilities. He raised the proportion of Strategic Air Command (SAC) strategic bombers on 15-minute ground alert from 25% to 50%, thus lessening their vulnerability to missile attack. In December 1961, he established the United States Strike Command (STRICOM). Authorized to draw forces when needed from the Strategic Army Corps (STRAC), the Tactical Air Command, and the airlift units of the Military Air Transport Service and the military services, Strike Command had the mission "to respond swiftly and with whatever force necessary to threats against the peace in any part of the world, reinforcing unified commands or... carrying out separate contingency operations." McNamara also increased long-range airlift and sealift capabilities and funds for space research and development. After reviewing the separate and often uncoordinated service efforts in intelligence and communications, McNamara in 1961 consolidated these functions in the Defense Intelligence Agency and the Defense Communications Agency (the latter originally established by Secretary Gates in 1960), having both report to the secretary of defense through the JCS. The end effect was to remove the Intelligence function from the control of the military and to put it under the control of the Secretary of Defense. In the same year, he set up the Defense Supply Agency to work toward unified supply procurement, distribution, and inventory management under the control of the Secretary of Defense rather than the uniformed military.

McNamara's institution of systems analysis as a basis for making key decisions on force requirements, weapon systems, and other matters occasioned much debate. Two of its main practitioners during the McNamara era, Alain C. Enthoven and K. Wayne Smith, described the concept as follows: "First, the word 'systems' indicates that every decision should be considered in as broad a context as necessary... The word 'analysis' emphasizes the need to reduce a complex problem to its component parts for better understanding. Systems analysis takes a complex problem and sorts out the tangle of significant factors so that each can be studied by the method most appropriate to it." Enthoven and Smith said they used mainly civilians as systems analysts because they could apply independent points of view to force planning. McNamara's tendency to take military advice into less account than had previous secretaries and to override military opinions contributed to his unpopularity with service leaders. It was also generally thought that Systems Analysis, rather than being objective, was tailored by the civilians to support decisions that McNamara had already made.

The most notable example of systems analysis was the Planning, Programming and Budgeting System (PPBS) instituted by United States Department of Defense Comptroller Charles J. Hitch. McNamara directed Hitch to analyze defense requirements systematically and produce a long-term, program-oriented Defense budget. PPBS evolved to become the heart of the McNamara management program. According to Enthoven and Smith, the basic ideas of PPBS were: "the attempt to put defense program issues into a broader context and to search for explicit measures of national need and adequacy"; "consideration of military needs and costs together"; "explicit consideration of alternatives at the top decision level"; "the active use of an analytical staff at the top policymaking levels"; "a plan combining both forces and costs which projected into the future the foreseeable implications of current decisions"; and "open and explicit analysis, that is, each analysis should be made available to all interested parties, so that they can examine the calculations, data, and assumptions and retrace the steps leading to the conclusions." In practice, the data produced by the analysis was so large and so complex that while it was available to all interested parties, none of them could challenge the conclusions.[17]

Among the management tools developed to implement PPBS were the Five Year Defense Plan (FYDP), the Draft Presidential Memorandum (DPM), the Readiness, Information and Control Tables, and the Development Concept Paper (DCP). The annual FYDP was a series of tables projecting forces for eight years and costs and manpower for five years in mission-oriented, rather than individual service, programs. By 1968, the FYDP covered ten military areas: strategic forces, general purpose forces, intelligence and communications, airlift and sealift, guard and reserve forces, research and development, central supply and maintenance, training and medical services, administration and related activities, and support of other nations.

The DPM—intended for the White House and usually prepared by the systems analysis office—was a method to study and analyze major defense issues. Sixteen DPMs appeared between 1961 and 1968 on such topics as strategic offensive and defensive forces, NATO strategy and force structure, military assistance, and tactical air forces. OSD sent the DPMs to the services and the JCS for comment; in making decisions, McNamara included in the DPM a statement of alternative approaches, force levels, and other factors. The DPM in its final form became a decision document. The DPM was hated by the JCS and uniformed military in that it cut their ability to communicate directly to the White House. The DPMs were also disliked because the systems analysis process was so heavyweight that it was impossible for any service to effectively challenge its conclusions.

The Development Concept Paper examined performance, schedule, cost estimates, and technical risks to provide a basis for determining whether to begin or continue a research and development program. But in practice, what it proved to be was a cost burden that became a barrier to entry for companies attempting to deal with the military. It aided the trend toward a few large non-competitive defense contractors serving the military. Rather than serving any useful purpose, the overhead necessary to generate information that was often in practice ignored resulted in increased costs throughout the system.

The Readiness, Information, and Control Tables provided data on specific projects, more detailed than in the FYDP, such as the tables for the Southeast Asia Deployment Plan, which recorded by month and quarter the schedule for deployment, consumption rates, and future projections of U.S. forces in Southeast Asia.

ABM

Toward the end of his term McNamara also opposed an anti-ballistic missile (ABM) system proposed for installation in the U.S. in defense against Soviet missiles, arguing the $40 billion "in itself is not the problem; the penetrability of the proposed shield is the problem."[18] Under pressure to proceed with the ABM program after it became clear that the Soviets had begun a similar project, McNamara finally agreed to a "light" system which he believed could protect against the far smaller number of Chinese missiles. However, he never believed it was wise for the United States to move in that direction because of psychological risks of relying too much on nuclear weaponry and that there would be pressure from many directions to build a larger system than would be militarily effective.[19]

He always believed that the best defense strategy for the U.S. was a parity of mutually assured destruction with the Soviet Union. An ABM system would be an ineffective weapon as compared to an increase in deployed nuclear missile capacity.

Cost reductions

McNamara's staff stressed systems analysis as an aid in decision making on weapon development and many other budget issues. The secretary believed that the United States could afford any amount needed for national security, but that "this ability does not excuse us from applying strict standards of effectiveness and efficiency to the way we spend our defense dollars.... You have to make a judgment on how much is enough." Acting on these principles, McNamara instituted a much-publicized cost reduction program, which, he reported, saved $14 billion in the five-year period beginning in 1961. Although he had to withstand a storm of criticism from senators and representatives from affected congressional districts, he closed many military bases and installations that he judged unnecessary to national security. He was equally determined about other cost-saving measures.[20]

Due to the nuclear arms race, the Vietnam War buildup and other projects, total obligational authority (TOA) increased greatly during the McNamara years. Fiscal year TOA increased from $48.4 billion in 1962 to $49.5 billion in 1965 (before the major Vietnam increases) to $74.9 billion in 1968, McNamara's last year in office (though he left office in February). Not until FY 1984 did DoD's total obligational authority surpass that of FY 1968 in constant dollars.

Program consolidation

One major hallmark of McNamara's cost reductions was the consolidation of programs from different services, most visibly in aircraft acquisition, believing that the redundancy created waste and unnecessary spending. McNamara directed the Air Force to adopt the Navy's F-4 Phantom and A-7 Corsair combat aircraft, a consolidation that was quite successful. Conversely, his actions in mandating a premature across-the-board adoption of the untested M16 rifle proved catastrophic when the weapons began to fail in combat. McNamara tried to extend his success by merging development programs as well, resulting in the TFX dual service F-111 project. It was to combine Navy requirements for an Fleet Air Defense (FAD) aircraft[21] and Air Force requirements for a tactical bomber. His experience in the corporate world led him to believe that adopting a single type for different missions and service would save money. He insisted on the General Dynamics entry over the DOD's preference for Boeing because of commonality issues. Though heralded as a fighter that could do everything (fast supersonic dash, slow carrier and short airfield landings, tactical strike, and even close air support), in the end it involved too many compromises to succeed at any of them. The Navy version was drastically overweight and difficult to land, and eventually canceled after a Grumman study showed it was incapable of matching the abilities of the newly revealed Soviet MiG-23 and MiG-25 aircraft. The F-111 would eventually find its niche as a tactical bomber and electronic warfare aircraft with the Air Force.

However, many analysts believe that even though the TFX project itself was a failure, McNamara was ahead of his time as the trend in fighter design has continued toward consolidation — the F-16 Falcon and F/A-18 Hornet emerged as multi-role fighters, and most modern designs combine many of the roles the TFX would have had. In many ways, the Joint Strike Fighter is seen as a rebirth of the TFX project, in that it purports to satisfy the needs of three American Air arms (as well as several foreign customers), fulfilling the roles of strike fighter, carrier-launched fighter, V/STOL, and close air support (and drawing many criticisms similar to those leveled against the TFX).

Vietnam War

During President John F. Kennedy's term, while McNamara was Secretary of Defense, America's troops in Vietnam increased from 900 to 16,000 advisers,[22] who were not supposed to engage in combat but rather to train the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. The number of combat advisers in Vietnam when Kennedy died vary depending upon source. The first military adviser deaths in Vietnam occurred in 1957 or 1959 under the Eisenhower Administration, which had infiltrated Vietnam, through the efforts of Stanley Sheinbaum, with an unknown number of CIA operatives and other special forces in addition to almost 700 advisers.[23][24]

The Truman and Eisenhower administrations had committed the United States to support the French and native anti-Communist forces in Vietnam in resisting efforts by the Communists in the North to unify the country, though neither administration established actual combat forces in the war. The U.S. role—initially limited to financial support, military advice and covert intelligence gathering—expanded after 1954 when the French withdrew. During the Kennedy administration, the U.S. military advisory group in South Vietnam steadily increased, with McNamara's concurrence, from 900 to 16,000.[22] U.S. involvement escalated after the Gulf of Tonkin incidents in August 1964, involving an attack on a U.S. Navy destroyer by North Vietnamese naval vessels.[25]

But declassified records from the Lyndon Johnson Library indicated that McNamara misled Johnson on the attack on a U.S. Navy destroyer by withholding calls against executing airstrikes from US Pacific Commanders. Instead, McNamara issued the strike orders without informing Johnson of the hold calls, constituting a usurping of the president’s constitutional power of decision on the use of military force.[26] McNamara was also instrumental in presenting the event to Congress and the public as justification for escalation of the war against the communists. The Vietnam War came to claim most of McNamara's time and energy. In 1995, McNamara met with former North Vietnam Defense Minister Vo Nguyen Giap who told his American counterpart that the Aug. 4 attack never happened, a conclusion McNamara came to accept.[27]

President Johnson ordered retaliatory air strikes on North Vietnamese naval bases and Congress approved almost unanimously the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, authorizing the president "to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the U.S. and to prevent further aggression." Regardless of the particulars of the incident, the larger issue would turn out to be the sweeping powers granted by the resolution. It gave Johnson virtually unfettered authority to expand retaliation for a relatively minor naval incident into a major land war involving 500,000 American soldiers. "The fundamental issue of Tonkin Gulf involved not deception but, rather, misuse of power bestowed by the resolution," McNamara wrote later.[28]

In 1965, in response to stepped up military activity by the Viet Cong in South Vietnam and their North Vietnamese allies, the U.S. began bombing North Vietnam, deployed large military forces and entered into combat in South Vietnam. McNamara's plan, supported by requests from top U.S. military commanders in Vietnam, led to the commitment of 485,000 troops by the end of 1967 and almost 535,000 by June 30, 1968. The casualty lists mounted as the number of troops and the intensity of fighting escalated. McNamara put in place a statistical strategy for victory in Vietnam. He concluded that there were a limited number of Viet Cong fighters in Vietnam and that a war of attrition would destroy them. He applied metrics (body counts) to determine how close to success his plan was.

Although he was a prime architect of the Vietnam War and repeatedly overruled the JCS on strategic matters, McNamara gradually became skeptical about whether the war could be won by deploying more troops to South Vietnam and intensifying the bombing of North Vietnam, a claim he would publish in a book years later. He also stated later that his support of the Vietnam War was given out of loyalty to administration policy. He traveled to Vietnam many times to study the situation firsthand and became increasingly reluctant to approve the large force increments requested by the military commanders.

McNamara said that the Domino Theory was the main reason for entering the Vietnam War. In the same interview he stated, "Kennedy hadn't said before he died whether, faced with the loss of Vietnam, he would [completely] withdraw; but I believe today that had he faced that choice, he would have withdrawn."[29]

Social equity

To commemorate President Harry S Truman's signing an order to end segregation in the military McNamara issued Directive 5120.36 on July 26, 1963. This directive, Equal Opportunity in the Armed Forces, dealt directly with the issue of racial and gender discrimination in areas surrounding military communities. The directive declared, "Every military commander has the responsibility to oppose discriminatory practices affecting his men and their dependents and to foster equal opportunity for them, not only in areas under his immediate control, but also in nearby communities where they may live or gather in off-duty hours." (para. II.C.)[30] Under the directive, commanding officers were obligated to use the economic power of the military to influence local businesses in their treatment of minorities and women. With the approval of the Secretary of Defense, the commanding officer could declare areas off-limits to military personnel for discriminatory practices.[31]

Departure

McNamara wrote of his close personal friendship with Jackie Kennedy, and how she demanded that he stop the killing in Vietnam.[32] As McNamara grew more and more controversial after 1966 and his differences with the President and the Joint Chiefs of Staff over Vietnam strategy became the subject of public speculation, frequent rumors surfaced that he would leave office. In an early November 1967 memorandum to Johnson, McNamara's recommendation to freeze troop levels, stop bombing North Vietnam and for the U.S. to hand over ground fighting to South Vietnam was rejected outright by the President. McNamara's recommendations amounted to his saying that the strategy of the United States in Vietnam which had been pursued to date had failed. McNamara later stated he "never heard back" from Johnson regarding the memo. Largely as a result, on November 29 of that year, McNamara announced his pending resignation and that he would become President of the World Bank. Other factors were the increasing intensity of the anti-war movement in the U.S., the approaching presidential campaign in which Johnson was expected to seek re-election, and McNamara's support—over the objections of the Joint Chiefs of Staff—of construction along the 17th parallel separating South and North Vietnam of a line of fortifications running from the coast of Vietnam into Laos. The President's announcement of McNamara's move to the World Bank stressed his stated interest in the job and that he deserved a change after seven years as Secretary of Defense, longer than any of his predecessors or successors.

Others give a different view of McNamara's departure from office. For example, Stanley Karnow in his book Vietnam: A History strongly suggests that McNamara was asked to leave by the President. McNamara himself expressed uncertainty about the question.[33]

McNamara left office on February 29, 1968; for his efforts, the President awarded him both the Medal of Freedom[34] and the Distinguished Service Medal.

Shortly after McNamara departed the Pentagon, he published The Essence of Security, discussing various aspects of his tenure and position on basic national security issues. He did not speak out again on defense issues or Vietnam until after he left the World Bank.

World Bank President

McNamara served as head of the World Bank from April 1968 to June 1981, when he turned 65.[35] In his 13 years at the Bank, he introduced key changes, most notably, shifting the Bank's focus toward targeted poverty reduction. He negotiated, with the conflicting countries represented on the Board, a growth in funds to channel credits for development, in the form of health, food, and education projects. He also instituted new methods of evaluating the effectiveness of funded projects. One notable project started during McNamara's tenure was the effort to prevent river blindness.[35]

The World Bank currently has a scholarship program under his name.[36]

As World Bank President, McNamara declared at the 1968 Annual Meeting of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group that countries permitting birth control practices would get preferential access to resources.

Post-World Bank activities and assessments

In 1982, McNamara joined several other former national security officials in urging that the United States pledge not to use nuclear weapons first in Europe in the event of hostilities; subsequently he proposed the elimination of nuclear weapons as an element of NATO's defense posture.

In 1993, Washington journalist Deborah Shapley published a 615-page biography of Robert McNamara entitled Promise and Power: the Life and Times of Robert McNamara. The last pages of her book made clear that while Ms. Shapley deeply admired certain aspects of McNamara the man, and the public servant, she had seen first-hand his need to manipulate the truth, as well as to tell it. Shapley concluded her book with these words: "For better and worse McNamara shaped much in today's world – and imprisoned himself. A little-known nineteenth century writer, F.W. Boreham, offers a summation: `We make our decisions. And then our decisions turn around and make us.'"

McNamara's memoir, In Retrospect, published in 1995, presented an account and analysis of the Vietnam War from his point of view. According to his lengthy New York Times obituary, "[h]e concluded well before leaving the Pentagon that the war was futile, but he did not share that insight with the public until late in life. In 1995, he took a stand against his own conduct of the war, confessing in a memoir that it was 'wrong, terribly wrong.'" In return, he faced a "firestorm of scorn" at that time.[3]

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara is a 2003 Errol Morris documentary consisting mostly of interviews with Robert McNamara and archival footage. It went on to win the Academy Award for Documentary Feature. The particular structure of this personal account is accomplished with the characteristics of an intimate dialog. As McNamara explains, it is a process of examining the experiences of his long and controversial period as the United States Secretary of Defense, as well as other periods of his personal and public life.[37] In this documentary he referred to the Vietnam War and he said, "None of our allies supported us. Not Japan, not Germany, not Britain or France. If we can't persuade nations with comparable values of the merit of our cause, we'd better reexamine our reasoning." (However, 60,000 Australians & 3,500 New Zealanders fought in the Vietnam War, where respectively 500 & 37 died, and 3,000 & 187 were wounded.[38][39])

The most striking part of the dialog is that he claims the Vietnam War was the result of the catastrophic failure of the American and Vietnamese leaderships to understand each other's intentions. The North Vietnamese were fighting an anti-colonial war of independence and the United States was fighting the Cold War. But the United States had no intention of colonizing Vietnam or even exerting the sort of control over it that the Soviet Union exerted over Eastern European countries. And Vietnam saw communist China largely as another threat to it, not an ally in a global war against capitalism. When McNamara visited Vietnam as part of the documentary, he asked his former counterpart about Chinese support for the north, and his counterpart asked if he had ever read a history textbook because China and Vietnam had been fighting each other for a thousand years.

His acknowledgement that the firebombing of Tokyo with General LeMay would have rightfully been considered a war crime had the US lost the war is also striking, especially given his own involvement in this action. Yet he stops short of expressing remorse given that he believed at the time that the action would save many American lives. The documentary contrasts the attitude of General Curtis LeMay, who believed that almost anything was justifiable in the name of military efficiency, with McNamara's more nuanced and indeed conflicted attitude.

The eleven lessons explored in the documentary are:

- Empathize with your enemy

- Rationality will not save us

- There's something beyond oneself

- Maximize efficiency

- Proportionality should be a guideline in war

- Get the data

- Belief and seeing are both often wrong

- Be prepared to reexamine your reasoning

- In order to do good, you may have to engage in evil

- Never say never

- You can't change human nature.

McNamara maintained his involvement in politics in his later years, delivering statements critical of the Bush administration's 2003 invasion of Iraq.[40] On January 5, 2006, McNamara and most living former Secretaries of Defense and Secretaries of State met briefly at the White House with President Bush to discuss the war.[41]

McNamara has been portrayed or fictionalized in several films[note 1] and in at least one popular video game.[note 2] Simon & Garfunkel's 1966 album, "Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme" contained a song entitled A Simple Desultory Philippic (or How I Was Robert McNamara'd into Submission).

Personal life

McNamara married Margaret Craig, his teenage sweetheart, on August 13, 1940. She was an accomplished cook, and Robert's favorite dish was reputed to be her beef bourguignon.[42] Margaret McNamara, a former teacher, used her position as a Cabinet spouse to launch a reading program for young children, Reading Is Fundamental, which became the largest literacy program in the country. She died of cancer in 1981.

The couple had two daughters and a son. The son Robert Craig McNamara, who as a student objected to the Vietnam War, is now a walnut and grape farmer in California.[43] He is the owner of Sierra Orchards in Winters, California. Daughter Kathleen McNamara Spears is a forester with the World Bank.[44] The second daughter is Margaret Elizabeth Pastor.[3]

In the Errol Morris documentary, McNamara reports that both he and his wife were stricken with polio shortly after the end of World War II. Although McNamara had a relatively short stay in the hospital, his wife's case was more serious and it was concern over meeting her medical bills that led to his decision to not return to Harvard but to enter private industry as a consultant at Ford Motor Company.

When working at Ford Motor Company, McNamara resided in Ann Arbor, Michigan, rather than the usual auto executive domains of Grosse Pointe, Birmingham, and Bloomfield Hills. He and his wife sought to remain connected with a university town (the University of Michigan) after their hopes of returning to Harvard after the war were put on hold.

In 1961, he was named Alumnus of the Year by the University of California, Berkeley.[45]

On September 29, 1972, a passenger on the ferry to Martha's Vineyard recognized McNamara on board and attempted to throw him into the ocean. McNamara declined to press charges. The man remained anonymous, but was interviewed years later by author Paul Hendrickson,[46] who quoted the attacker as saying, "I just wanted to confront (McNamara) on Vietnam."

After his wife's death, McNamara dated Katharine Graham, with whom he had been friends since the early 1960s. Graham died in 2001.

In September 2004, McNamara wed Diana Masieri Byfield, an Italian-born widow who had lived in the United States for more than 40 years. It was her second marriage. She was married for more than three decades to Ernest Byfield, a former OSS officer and Chicago hotel heir whose mother, Gladys Tartiere, leased her 400 acres (1.6 km2), Glen Ora estate in Middleburg, Virginia to John F. Kennedy during his presidency.[47][48]

McNamara was, at the end of his life, a life trustee on the Board of Trustees of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), a trustee of the Economists for Peace and Security, a trustee of the American University of Nigeria, and an honorary trustee for the Brookings Institution.

McNamara died in his sleep, at his home in Washington, D.C., early in the morning, at 5:30 a.m. on July 6, 2009, at the age of 93.[49][50] He is buried at the Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.

See also

- List of California Institute of Technology trustees

- List of Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- American University of Nigeria, Yola, Nigeria

- List of United States political appointments that crossed party lines

- Project Dye Marker

- The Fog of War

- List of Eagle Scouts

Works

- (1968) The Essence of Security: Reflections in Office. New York, Harper & Row, 1968; London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1968. ISBN 0-340-10950-5.

- (1973) One hundred countries, two billion people: the dimensions of development. New York, Praeger Publishers, 1973. ASIN B001P51NUA[51]

- (1981) The McNamara years at the World Bank: major policy addresses of Robert S. McNamara, 1968-1981; with forewords by Helmut Schmidt and Léopold Senghor. Baltimore: Published for the World Bank by the Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-8018-2685-3.

- (1985) The challenges for sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: 1985.

- (1986) Blundering into disaster: surviving the first century of the nuclear age. New York: Pantheon Books, 1986. ISBN 0-394-55850-2 (hardcover); ISBN 0-394-74987-1 (pbk.).

- (1989) Out of the cold: new thinking for American foreign and defense policy in the 21st century. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989. ISBN 0-671-68983-5.

- (1992) The changing nature of global security and its impact on South Asia. Washington, DC: Washington Council on Non-Proliferation, 1992.

- (1995) In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. (with Brian VanDeMark.) New York: Times Books, 1995. ISBN 0-8129-2523-8; New York: Vintage Books, 1996. ISBN 0-679-76749-5.

- (1999) Argument without end: in search of answers to the Vietnam tragedy. (Robert S. McNamara, James G. Blight, and Robert K. Brigham.) New York: Public Affairs, 1999. ISBN 1-891620-22-3 (hc).

- (2001) Wilson’s ghost: reducing the risk of conflict, killing, and catastrophe in the 21st century. (Robert S. McNamara and James G. Blight.) New York: Public Affairs, 2001. ISBN 1-891620-89-4.

Notes

- ↑ The Missiles of October; Thirteen Days; Path to War; Transformers: Dark of the Moon

- ↑ In Call of Duty: Black Ops McNamara and Presidents John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon make common cause with Fidel Castro against attacking zombies.

References

- ↑ Six for the Kennedy Cabinet, Time, December 26, 1960.

- ↑ "Missile Gaps and Other Broken Promises". The New York Times. February 10, 2009. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Weiner, Tim (July 6, 2009). "Robert S. McNamara, Architect of a Futile War, Dies at 93 - Obituary". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ↑ "Robert S. McNamara, Architect of a Futile War, Dies at 93". The New York Times. July 7, 2009.

- ↑ Radin, Beryl (2000), Beyond Machiavelli : Policy Analysis Comes of Age. Georgetown University Press.

- ↑ network.nationalpost.com, Vietnam-era U.S. Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara dead: report,, 6 July 2009, retrieved 6 July 2009

- ↑ sg.msn.com, Former US defense secretary McNamara dies, 6 July 2009, retrieved 6 July 2009

- ↑ booknotes.org, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (interview), 23 April 1995, retrieved 31 December 2011

- ↑ 1933 Piedmont High Clan-O-Log

- ↑ http://www.phigam.org, Robert McNamara (California at Berkeley 1937) Passes Ad Astra, 6 July 2009, retrieved 9 July 2009

- ↑ Rich Frank: Downfall, Random House, 1999.

- ↑ AmericanHeritage.com, The Outsider

- ↑ Sorensen, Ted. Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History.

- ↑ McNamara, Robert S. In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam.

- ↑ Karnow (1997), p. 271

- ↑ Defenselink.mil

- ↑ Amadae, SM (2003). Rationalizing Capitalist Democracy: The Cold War Origins of Rational Choice Liberalism. Chapter 1: Chicago University Press. pp. 27–82. ISBN 0-226-01654-4.

- ↑ McNamara, Robert S. (1968), The Essence of Security: Reflections in Office, p. 64

- ↑ McNamara, Robert S. (1968), The Essence of Security: Reflections in Office, p. 164

- ↑ Archived January 12, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ General Dynamics-Grumman F-111B

- 1 2 "Vietnam War". Swarthmore College Peace Collection. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Military Assistance Advisory Group wikipedia

- ↑ MacKenzie, Angus,Secrets: The CIA's War at Home,University of California Press, 1997

- ↑ Hanyok article (page 177)

- ↑ "Robert S. McNamara and the Real Tonkin Gulf Deception".

- ↑ McNamara, In Retrospect, p. 128.

- ↑ McNamara, In Retrospect, p. 142

- ↑ Transcript of the film The Fog of War

- ↑ The Secretary of the Army's Senior Review Panel on Sexual Harassment p 127

- ↑ While the directive was passed in 1963, it was not until 1967 that the first non-military establishment was declared off-limits. In 1970 the requirement that commanding officers first obtain permission from the Secretary of Defense was lifted. Heather Antecol and Deborah Cobb-Clark, Racial and Ethnic Harassment in Local Communities. October 4, 2005. p 8

- ↑ McNamara, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, 1995, p. 257-258.

- ↑ In The Fog of War he recounts saying to a friend, "Even to this day, Kay, I don't know whether I quit or was fired?" (See transcript)

- ↑ Blight, James. The fog of war: lessons from the life of Robert S. McNamara. p. 203. ISBN 0-7425-4221-1.

- 1 2 "Pages from World Bank History - Bank Pays Tribute to Robert McNamara". Archives. World Bank. March 21, 2003. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ↑ "Robert S. McNamara Fellowships Program". Scholarships. World Bank. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ↑ Blight, James G.; Lang, Janet M. (2007). "Robert Mcnamara: Then & Now". Dædalus 136 (1): 120–131. JSTOR 20028094.

- ↑ Australian War Memorial: The Vietnam War 1962 - 75 http://www.awm.gov.au/atwar/vietnam.asp

- ↑ The Vietnam War | NZHistory, New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Doug Saunders (2004-01-25). "'It's Just Wrong What We're Doing'". Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Sanger, David E. (2006-01-06). "Visited by a Host of Administrations Past, Bush Hears Some Chastening Words". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ Who's Who in the Kitchen, 1961 - Reprint 2013. p. 10.

- ↑ "2001 Award of Distinction Recipients — College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences". University of California, Davis. 2007-11-19. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

Craig McNamara is owner of Sierra Orchards, a diversified farming operation producing walnuts and grape rootstock. He is a California Agricultural Leadership Program graduate, American Leadership Forum senior fellow and College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Dean's Advisory Council member. McNamara helped structure a biologically integrated orchard system that became the model for UC/SAREP (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program) and created the FARMS Leadership Program, introducing rural and urban high school students to sustainable farming, science and technology. He was one of 10 U.S. representatives at the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome.

- ↑ "Kathleen McNamara Weds J. S. Spears". New York Times. January 1, 1987. p. 16. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ↑ "List of Alumni of the Year"

- ↑ Hendrickson, Paul: The Living and the Dead: Robert McNamara and Five Lives of a Lost War. Vintage, 1997. ISBN 0-679-78117-X.

- ↑ Roxanne Roberts (2004-09-07). "Wedding Bells for Robert McNamara". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Obituaries; Gladys R. Tartiere, Philanthropist, Dies". The Washington Post - ProQuest Archiver. 1993-05-03.

- ↑ Page, Susan (6 July 2009). "Ex-Defense secretary Robert McNamara dies at 93". USA Today.

- ↑ "Robert S. McNamara, Former Defense Secretary, Dies at 93". New York Times, July 6, 2009.

- ↑ Google Books

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert McNamara |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert McNamara. |

- Robert McNamara on the JFK and LBJ White House Tapes

- AP Obituary in The Washington Post

- The Economist obituary

- Robert McNamara - Daily Telegraph obituary

- McNamara's Evil Lives On by Robert Scheer, The Nation, July 8, 2009

- McNamara and Agent Orange

- Biography of Robert Strange McNamara (website)

- Historical Office US Department of Defense

- Interview about the Cuban Missile Crisis for the WGBH series

- Interview about nuclear strategy

- Annotated bibliography for Robert McNamara from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Oral History Interviews with Robert McNamara, from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Booknotes interview with McNamara on In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, April 23, 1995.

- Booknotes interview with Deborah Shapley on Promise and Power: The Life and Times of Robert McNamara, March 21, 1993.

- Booknotes interview with Paul Hendrickson on The Living and the Dead: Robert McNamara and Five Lives of a Lost War, October 27, 1996.

- "Robert McNamara". Find a Grave. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- Conversations with History: Robert S. McNamara, from the University of California Television (UCTV)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas S. Gates Jr. |

U.S. Secretary of Defense Served under: John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson 1961–1968 |

Succeeded by Clark Clifford |

| Non-profit organization positions | ||

| Preceded by George David Woods |

President of the World Bank 1968–1981 |

Succeeded by Alden W. Clausen |

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|