Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing a commercially successful steamboat called Clermont. That steamboat went with passengers from New York City to Albany and back again, a round trip of 300 miles, in 62 hours. In 1800, he was commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte to design the "Nautilus", which was the first practical submarine in history.[1] He is also credited with inventing some of the world's earliest naval torpedoes for use by the British Royal Navy.[2]

Fulton became interested in steam engines and using them on steamboats in 1777 when he was around age 12 and visited state delegate William Henry of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who himself had earlier learned about inventor James Watt, (1736-1819), and his Watt steam engine on a visit to England.

Early life

Robert Fulton was born on a farm in Little Britain, Pennsylvania, on November 14, 1765. He had at least three sisters – Isabella, Elizabeth, and Mary, and a younger brother, Abraham. He then married Harriet Livingston and had four children, Julia, Mary, Cornelia, and Robert. His father, Robert, had been a close friend to the father of painter Benjamin West, (1738-1820). Fulton later met West in England and they became friends.[3]

Fulton stayed in Philadelphia for six years, where he painted portraits and landscapes, drew houses and machinery, and was able to send money home to help support his mother. In 1785 he bought a farm at Hopewell Township in Washington County for £80 Sterling and moved his mother and family into it. While in Philadelphia, he met Benjamin Franklin, (1705/1706-1790), then known not only for his political and writing abilities but his scientific and inventing knowledge, and other prominent figures. At age 23 he decided to visit Europe.

Education and work

Fulton came to England in 1786, carrying several letters of introduction to Americans abroad from the individuals he had met in Philadelphia. He had already corresponded with Benjamin West, and West took Fulton into his home, where Fulton lived for several years. Fulton gained many commissions painting portraits and landscapes, which allowed him to support himself, but he continually experimented with mechanical inventions.[3]

He became caught up in the enthusiasm of the "Canal Mania" and in 1793 began developing his ideas for tub-boat canals with inclined planes instead of locks. He obtained a patent for this idea in 1794 and also began working on ideas for the steam power of boats. He published a pamphlet about canals and patented a dredging machine and several other inventions. In 1794 he moved to Manchester to gain practical knowledge of English canal engineering. Whilst there he became friendly with Robert Owen, the cotton manufacturer and early socialist. Owen agreed to finance the development and promotion of his designs for inclined planes and earth-digging machines and was instrumental in introducing him to a canal company where he was awarded a sub-contract. However, this practical experience was not a success and he gave up the contract after a short time.[4]

In 1797 he went to Paris where his fame as an inventor was well known. In Paris, then along with London, the scientific centers of the 18th Century world, Fulton studied languages French, and German, along with mathematics and chemistry. He began to design torpedoes and submarines. In Paris, Fulton met James Rumsey, (1743-1792), who sat for a portrait in West's studio, where Fulton was an apprentice. Rumsey was an inventor from Virginia who ran his own first steamboat up the Potomac River near Shepherdstown, then in Virginia in 1786. As early as 1793, Fulton proposed plans for steam-powered vessels to both the United States and British governments, and in England he met the Duke of Bridgewater (Francis Egerton), (1736-1803), whose canal, the first to be constructed in Britain, was being used for trials of a steam tug. Fulton became very enthusiastic about the canals and in 1796 wrote a treatise on canal construction, suggesting improvements to locks and other features. Working for the Duke of Bridgewater between 1796 and 1799, he had a boat constructed in the Duke's timber yard, under the supervision of Benjamin Powell. After installation of the machinery supplied by the engineers Bateman and Sherratt of Salford, the boat was duly christened "Bonaparte" in honour of Fulton having served under Napoleon. After expensive trials, because of the configuration of the design,it was feared the paddles may damage the clay lining of the canal and the experiment was eventually abandoned. In 1801 the Duke, impressed by the "Charlotte Dundas" constructed by William Symington, (1764-1831), decided to order eight of such vessels for his canal, but when he died in 1803, the order was cancelled. Symington had successfully tried steamboats in 1788, and it seems probable that Fulton was aware of these developments.

The first successful trial run of a steamboat had been made several years earlier by inventor John Fitch, (1743-1798), on the Delaware River on August 22, 1787, in the presence of delegates from the Constitutional Convention, then observing and taking a break from its summer-long sessions at Independence Hall. It was propelled by a bank of oars on either side of the boat. The following year Fitch launched a 60-foot (18 m) boat powered by a steam engine driving several stern mounted oars. These oars paddled in a manner similar to the motion of a swimming duck's feet. With this boat he carried up to thirty passengers on numerous round-trip voyages on the upper Delaware River between Philadelphia and Burlington, New Jersey.

Fitch was granted a patent on August 26, 1791, after a battle with Rumsey, who had created a similar invention. Unfortunately the newly created Patent Commission did not award the broad monopoly patent that Fitch had asked for, but a patent of the modern kind, for the new design of Fitch's steamboat. It also awarded patents to Rumsey and John Stevens, (1749-1838), for their steamboat designs, and the loss of a monopoly caused many of Fitch's investors to leave his company. While his boats were mechanically successful, Fitch failed to pay sufficient attention to construction and operating costs and was unable to justify the economic benefits of steam navigation. It was Fulton who would turn Fitch's idea into a more profitable proposition decades later.

In 1797, Fulton went to France, where Claude de Jouffroy (1751-1832), had made a working paddle steamer in 1783, and commenced experimenting with submarine torpedoes and torpedo boats. Fulton is the exhibitor of the first panorama painting to be shown in Paris, which was complete by 1800 "Vue de Paris depuis les Tuilerie" painted by Pierre Prévost, (1764-1823), Jean Mouchet and Denis Fontaine. The street where his panorama was shown is still called "'Rue des Panoramas'" (Panorama Street) today.[5]

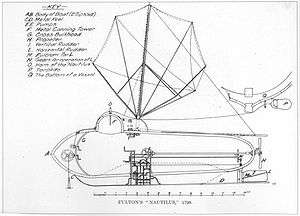

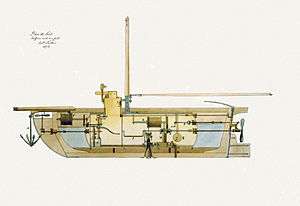

Fulton designed the first working submarine, the "Nautilus" between 1793 and 1797, while living in France. When tested his submarine went underwater for 17 minutes in 25 feet of water. He asked the government to subsidize its construction but he was turned down twice. Eventually he approached the Minister of Marine himself and in 1800 was granted permission to build.[6] The shipyard Perrier in Rouen built it and it sailed first in July 1800 on the Seine River in the same city.

In France, Fulton also met Robert R. Livingston, (1746-1813), who was appointed U.S. Ambassador to France in 1801, who was also of a scientifically curious mind, and they decided to build a steamboat together and try running it on the Seine. Fulton experimented with the water resistance of various hull shapes, made drawings and models, and had a steamboat constructed. At the first trial the boat ran perfectly, but the hull was later rebuilt and strengthened, and on August 9, 1803, this boat steamed up the River Seine, but sank. The boat was 66 feet (20.1 m) long, 8 feet (2.4 m) beam, and made between 3 and 4 miles per hour (4.8 and 6.4 km/h) against the current.

In 1804, Fulton switched allegiance and moved to England, where he was commissioned by the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, (1759-1806), to build a range of weapons for use by the Royal Navy during Napoleon's invasion scares. Among his inventions were the world's first modern naval "torpedoes" (modern "mines"), which were tested, along with several other of his inventions, during the 1804 Raid on Boulogne, but met with limited success. Although he continued to develop his inventions with the British until 1806, the decisive naval victory by Admiral Horatio Nelson at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar greatly reduced the risk of French invasion, and Fulton found himself being increasingly ignored.[2]

In 1806, Fulton returned to America and married Harriet Livingston, the niece of Robert Livingston and daughter of Walter Livingston. They had four children: Robert, Julia, Mary and Cornelia. In 1807, Fulton and Livingston together built the first commercial steamboat, the "North River Steamboat" (later known as the "Clermont"), which carried passengers between New York City and upstream to the state capital Albany, New York. The Clermont was able to make the 150-mile trip in 32 hours. From 1811 until his death, Fulton was appointed by the Governor of New York, a member of the Erie Canal Commission.

Fulton's final design was the floating battery "Demologos" the world's first steam-driven warship built for the United States Navy for the War of 1812. The heavy vessel was not completed until after his death and was renamed the "Fulton" in his honor.

From October 1811 to January 1812, Fulton, along with Livingston and Nicholas Isaac Roosevelt (1787-1854), worked together on a joint project to build and travel from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on their specially designed and built a new steamboat "New Orleans" solid enough for a long trip down the mid-western Ohio River, with stops at Wheeling, Virginia, Cincinnati, Ohio, past the "Falls of the Ohio" at Louisville, Kentucky, to near Cairo, Illinois and the juncture with the Mississippi River, past St. Louis and follow the "Big Muddy" as it was acquiring the nickname, all the way down past Memphis, Tennessee and Natchez, Mississippi to the city of New Orleans on the Gulf of Mexico coast, this just a decade after the United States had acquired the Louisiana Territory from France and the rivers were not well settled, mapped or protected. By achieving this first breaking voyage and also proving the ability of the boat to reverse and go back upstream, changed the entire transportation outlook for the American heartland.

Fulton was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1814.[7]

Fulton died in 1815 in New York City from tuberculosis (then known as "consumption"). He had been walking home on the frozen Hudson River when one of his friends, Addis Emmet, fell through the ice. In the attempt to rescue his friend, Fulton got soaked with icy water and on the journey home he caught pneumonia. When he got home his sickness worsened. He contracted consumption and died at 49 years old. He is buried in the Trinity Church Cemetery for Trinity Church (Episcopal) at Wall Street in New York City, alongside other famous Americans such as former U.S. Secretaries of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton and Albert Gallatin. His descendants include former Major League Baseball pitcher Cory Lidle.[8]

Posthumous honors

In 1816, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania donated a marble statue of Fulton to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol. Fulton was also honored for his development of steamship technology in New York City's Hudson-Fulton Celebration of the Centennial in 1909. A replica of his first steam-powered steam vessel, the "Clermont", was built for the occasion.

Many places in the U.S. are named for Robert Fulton, including:

- Fulton Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- Fulton Elementary School, Fulton Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania[9]

- Fulton Steamboat Inn, hotel in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- Robert Fulton School, Philadelphia

- Fulton Elementary School, Dubuque, Iowa

- Robert Fulton Fire Company, Fulton Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- Robert Fulton Highway, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- Fulton Opera House, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

- Robert Fulton Drive in Columbia, Howard County, Maryland

- Robert Fulton Drive in Reston, Virginia

- Fulton Avenue in Sacramento, California

- Fulton Neighborhood in Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Fulton Street in Brooklyn, New York

- BMT Fulton Street Line subway line

- IND Fulton Street Line subway line

- Fulton Street in Manhattan

- Fulton Center in Manhattan

- Fulton Street (New York City Subway) subway station

- Fulton Street in Massapequa Park, New York

- Fulton Street in New Orleans, Louisiana

- Fulton Street in Alcoa, Tennessee

- Fulton Street in San Francisco, California

- Fulton Street in Anaheim, California

- Fulton County, Ohio

- Fulton County, Indiana

- Fulton County, Kentucky

- Fulton County, Illinois

- Fulton County, Pennsylvania

- Fulton County, New York

- Fulton, Mississippi

- Fulton, Missouri[10]

- Fulton, Arkansas

- Fulton, Oswego County, New York

- Fulton, Schoharie County, New York

- Fulton Chain Lakes, New York

- Fultonham, Ohio

- Fultonville, New York

- Fulton Hall, State Quad, University at Albany, (State University of New York at Albany)

- Fulton Park, New York City

Five ships of the United States Navy have borne the name "U.S.S. Fulton" in honor of Robert Fulton.

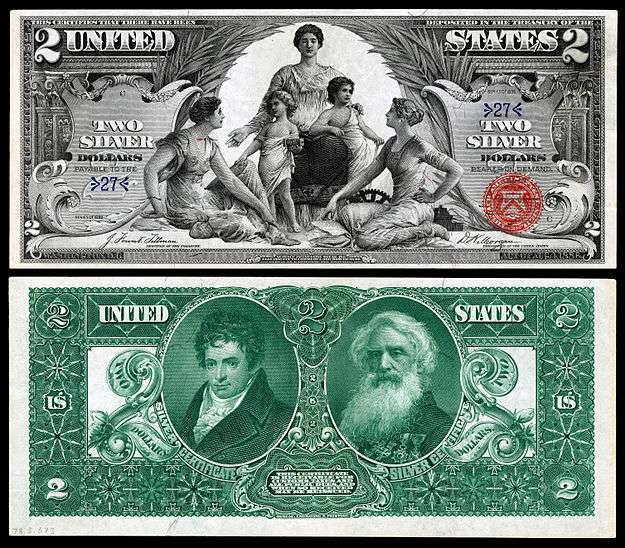

from the United States Treasury

Bronze statues of Fulton and Christopher Columbus represent commerce on the balustrade of the galleries of the Main Reading Room in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. They are two of 16 historical figures, each pair representing one of the 8 pillars of civilization.

In 2006, he was inducted into the "National Inventors Hall of Fame" in Alexandria, Virginia.[11]

In popular culture

A probably largely fictionalised account of Fulton's role was produced by BBC children's television. In the first season, "Triton" (1968), two British naval officers, Captain Belwether and Lieutenant Lamb, are involved in spying on Fulton while he is working for the French. In the second season, "Pegasus" (1969), they are surprised to find themselves working with him after he changed sides.

20th Century-Fox in 1940 released the film 'Little Old New York, a highly fictional telling of Fulton's life from his arrival in New York to the first sailing of the Clermont. British actor Richard Greene stars as Fulton with Brenda Joyce as Harriet Livingston. Much attention is given to Alice Faye and Fred MacMurray as wharf friends who help Fulton realize his dream amid problem after problem. It was based on a play by Rida Johnson Young. The views of an 1807 New York harbor are particularly elaborate and convincing.

In the children's TV series "TUGS" a steam powered ferry is named the Fulton Ferry, named after the Fulton Ferry Company, founded by Fulton in 1814.

A Robert Fulton cartoon character appears in the Casper the Friendly Ghost short film titled "Red, White, and Boo."

Author James McGee used Fulton's experiments in early submarine warfare (against wooden warships) as a major plot element in his novel "Ratcatcher".

"Invasion", ISBN 9780340961155, the tenth novel in the "Kydd", early 19th Century/"Napoleonic Wars" naval warfare series by Julian Stockwin, also uses Fulton and his submarine as an important plot element.

In the George and Ira Gershwin song, "They All Laughed", in a listing of concepts the public initially thought of as folly, "Fulton and his steamboat, Hershey and his chocolate bar" are cited.

Additionally, he is referenced in The Beach Boys rock group song "Steamboat" (Dennis Wilson/Jack Rieley) from the 1973 record album "Holland".

In the "Simpsons" television series episode, "The Wettest Stories Ever Told", when Marge, playing a Tahitian ruler, mentions Fulton in the line, "Tell me, has Robert Fulton invented the steamboat yet?" as they have no communication with the outside world, Jimbo's character replies "Any day now", referring to Fulton's "Clermont", ironically and erroneously suggesting that news of Fulton's invention has actually reached her and others already, despite his steamboat not being invented until 1807.

Gallery

-

Fulton presents his steamship to Bonaparte in 1803

-

Submarine design in cross section by Robert Fulton, 1806

-

Portrait

-

Robert Fulton's tombstone at Trinity Church (Episcopal) in New York City

-

Fulton sculpture by Caspar Buberl at the Brooklyn Museum, 1872

-

The marble statue by Howard Roberts in Statuary Hall of the United States Capitol, 1878-83.

-

Hudson-Fulton Celebration commemorative stamp, 1909 issue.

-

200th Anniversary commemorative stamp, 1965 issue, based on the Houdon bust.

Publications

- Torpedo war, and submarine explosions published 1810.

- A Treatise on the Improvement of Canal Navigation, 1796. From the University of Georgia Libraries in DjVu & layered PDF formats.

- A Treatise on the Improvement of Canal Navigation 1796. From Rare Book Room.

See also

References

- ↑ American Treasures of the Library of Congress: "Fulton's Submarine"

- 1 2 Best, Nicholas (2005). Trafalgar: The Untold Story of the Greatest Sea Battle in History. London: Phoenix. ISBN 0-7538-2095-1.

- 1 2 Buckman, David Lear (1907). Old Steamboat Days on The Hudson River. The Grafton Press. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010.

- ↑ Graham Boyes - The Peak Forest Canal - ISBN 9780901461 59 9

- ↑ Alice Crary Sutcliffe, Robert Fulton and the "Clermont", page 63 .

- ↑ Burgess, Robert Forrest (1975). Ships Beneath the Sea. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-008958-7.

- ↑ "MemberListF". American Antiquarian Society.

- ↑ "Lidle dies after plane crashes into NYC high-rise". ESPN.com.

- ↑ "The School District of Lancaster".

- ↑ Eaton, David Wolfe (1916). How Missouri Counties, Towns and Streams Were Named. The State Historical Society of Missouri. p. 267.

- ↑ National Inventors Hall of Fame

Sources

- This article contains content first published in 1909 as Old Steamboat Days on The Hudson River.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Fulton. |

- Robert Fulton Birthplace

- Photos of Fulton's Birthplace

- An article on Fulton and the War of 1812

- William Symington

- CHAPTER XIII: ROBERT FULTON in Great Fortunes, and How They Were Made (1871), by James D. McCabe, Jr., Illustrated by G. F. and E. B. Bensell, a Project Gutenberg eBook.

- 1911 Britannica biography

- Buckman, David Lear (1907). Old Steamboat Days on The Hudson River. The Grafton Press.

- Examples of art by Robert Fulton at the Art Renewal Center

- Robert H Thurston, A history of the growth of the steam-engine. Chapter V The Modern Steam Engine

- Iles, George (1912), Leading American Inventors, New York: Henry Holt and Company, pp. 40–75

- Booknotes interview with Kirkpatrick Sale on The Fire of His Genius: Robert Fulton and the American Dream, November 25, 2001.

- Collection of Robert Fulton manuscripts - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

| ||||||

|