Polish Righteous Among the Nations

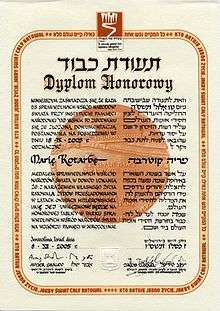

| Medals and diplomas awarded at a ceremony in the Polish Senate on 17 April 2012 | |

|

There are 6,532 Polish men and women recognized as Righteous by the State of Israel |

| Righteous Among the Nations |

|---|

| Notable individuals |

| By country |

The citizens of Poland have the world's highest count of individuals who have been recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations for saving Jews from extermination during the Holocaust in World War II. There are 6,532 Polish men and women recognized as Righteous to this day, over a quarter of the total number of 24,811[1] awards.

It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of Poles concealed and aided hundreds of thousands of their Polish-Jewish neighbors.[2][3] Many of these initiatives were carried out by individuals, but there also existed organized networks of Polish resistance which were dedicated to aiding Jews – most notably, the Żegota organization.

In German-occupied Poland the task of rescuing Jews was especially difficult and dangerous. All household members were punished by death if a Jew was found concealed in their home or on their property.[4] It is estimated that the number of Poles who were killed by the Nazis for aiding Jews was as high as tens of thousands, 704 of whom were posthumously honored with medals.[2][5][6]

Activities

Before World War II, Poland's Jewish community had numbered between 3,300,000[7] and 3,500,000 persons – about 10 percent of the country's total population. During World War II, Germany's Nazi regime sent millions of deportees from every European country to the concentration camps it set up in the General Government in occupied Poland.[8] Soon after war had broken out, the Germans began their extermination of Polish Jews, ethnic Polish, Romani, Russians, Czech, and others minorities of Poland. Most were quickly rounded up and imprisoned in ghettos, which they were forbidden to leave.

As it became apparent that, not only were conditions in the ghettos terrible (hunger, diseases, etc.), but that the Jews were being singled out for extermination at Nazi concentration camps, they increasingly tried to escape and hide in order to survive the war.[9] Many Polish Gentiles concealed hundreds of thousands of their Jewish neighbors. Many of these efforts arose spontaneously from individual initiatives, but there were also organized networks dedicated to aiding the Jews.[10]

Most notably, in September 1942 a Provisional Committee to Aid Jews (Tymczasowy Komitet Pomocy Żydom) was founded on the initiative of Polish novelist Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, of the famous artistic and literary Kossak family. This body soon became the Council for Aid to Jews (Rada Pomocy Żydom), known by the codename Żegota, with Julian Grobelny as its president and Irena Sendler as head of its children's section.[11][12]

It is not exactly known how many Jews were helped by Żegota, but at one point in 1943 it had 2,500 Jewish children under its care in Warsaw alone. At the end of the war, Sendler attempted to locate their parents but nearly all of them had died at Treblinka. It is estimated that about half of the Jews who survived the war (thus over 50,000) were aided in some shape or form by Żegota.[13]

In numerous instances, Jews were saved by the entire communities, with everyone engaged,[14] such as in the villages of Markowa[15] and Głuchów near Łańcut,[16] Główne, Ozorków, Borkowo near Sierpc, Dąbrowica near Ulanów, in Głupianka near Otwock,[17] Teresin near Chełm,[18] Rudka, Jedlanka, Makoszka, Tyśmienica, and Bójki in Parczew-Ostrów Lubelski area,[19] and Mętów, near Głusk. Numerous families who concealed their Jewish neighbors paid the ultimate price for doing so.[15] Most notably, several hundred Poles were massacred in Słonim. In Huta Stara near Buczacz, all Polish Christians and the Jewish countrymen they protected were burned alive in a church.[20]

Risk

| Warning of death penalty for saving Jews | |

|---|---|

|

NOTICE

Concerning: According to this decree, those knowingly helping these Jews by providing shelter, supplying food, or selling them foodstuffs are also subject to the death penalty. This is a categorical warning to the non-Jewish population against: Dr. Franke |

After the occupation of Poland, the Nazis separated the ghettos, with ethnic Poles on the "Aryan side" and the Jews on the "Jewish side". Anyone from the Aryan side found assisting those on the Jewish side in obtaining food was subject to the death penalty.[21][22] Capital punishment of entire families, for aiding Jews, was the most draconian such Nazi practice against any nation in occupied Europe.[4][23][24] On 10 November 1941, the death penalty was expanded by Hans Frank to apply to Poles who helped Jews "in any way: by taking them in for the night, giving them a lift in a vehicle of any kind" or "feed[ing] runaway Jews or sell[ing] them foodstuffs". The law was made public by posters distributed in all major cities. Polish rescuers were fully conscious of the dangers facing them and their families, not only from the Germans, but also from betrayers (see:szmalcownik) within the local population.[25]

The Nazis implemented another law, forbidding Poles from buying from Jewish shops under penalty of death.[26]

Over 700 Polish "Righteous Among the Nations" received their medals of honor posthumously, having been murdered by the Germans for aiding or sheltering their Jewish neighbors.[5] Estimates of the number of Poles who were killed for aiding Jews range in the tens of thousands.[2][5]

Gunnar S. Paulsson, in his work on history of the Jews of Warsaw, has demonstrated that, despite the much harsher conditions, Warsaw's Polish residents managed to support and conceal the same percentage of Jews as did the residents of cities in safer, supposedly less antisemitic countries of Western Europe.[27]

Numbers

There are 6,532 officially recognized Polish Righteous—the highest count among nations of the world. At a 1979 international historical conference dedicated to Holocaust rescuers, J. Friedman said in reference to Poland: "If we knew the names of all the noble people who risked their lives to save the Jews, the area around Yad Vashem would be full of trees and would turn into a forest."[3]

Hans G. Furth holds that the number of Poles who helped Jews is greatly underestimated and there might have been as many as 1,200,000 Polish rescuers.[3] Władysław Bartoszewski, a wartime member of Żegota, estimates that "at least several hundred thousand Poles... participated in various ways and forms in the rescue action."[2] Recent research supports estimates that about a million Poles were involved in such rescue efforts,[2] "but some estimates go as high as 3 million"[2] (the total prewar population of Polish citizens, including Jews, was estimated at 35,100,000, including 23,900,000 ethnic Poles).[7]

How many people in Poland rescued Jews? Of those that meet Yad Vashem's criteria – perhaps 100,000. Of those that offered minor forms of help – perhaps two or three times as many. Of those who were passively protective – undoubtedly the majority of the population. — Gunnar S. Paulsson [28]

Scholars still disagree on exact numbers. Father John T. Pawlikowski (a Servite priest from Chicago)[29] remarked that the hundreds of thousands of rescuers strike him as inflated.[30]

Misconceptions

The Republic of Poland was a multicultural country before World War II, with almost a third of its population originating from the minority groups: 13.9% Ukrainians; 10% Jews; 3.1% Belarusians; 2.3% Germans and 3.4% percent Czechs, Lithuanians and Russians. A number of ethnically German men from Poland joined the Nazi formations already in 1940.[31] The presence of sizeable German and pro-German minorities constituted a grave danger for the Catholic Poles who attempted to help ghettoised Jews.[32]

The local population in Soviet occupied eastern Poland prior to German Operation Barbarossa of 1941, had witnessed the repressions and mass deportation of up to 1.5 million ethnic Poles to Siberia, conducted by the NKVD,[33] with some of the local Jews collaborating with them and forming armed militias. There were also incidents of Jewish Communists betraying Polish victims to the NKVD.[34][35] The Anti-Semitic attitudes in those areas had been exploited by the Nazi Einsatzgruppen who induced anti-Jewish pogroms on the order of Reinhard Heydrich.[36][37] A total of 31 deadly pogroms were carried out throughout the region in conjunction with indigenous auxiliary police.[38] The Ukrainian People's Militia spread terror across dozens of cities with the blessings of the SS,[39] including Lwów (Lemberg), Tarnopol, Stanisławów, Łuck, Drohobycz, as well as Dubno, Kołomyja, Kostopol, Sarny, Złoczów and numerous other towns.[40] Further north-west, during the massacre in Jedwabne, a group of ethnic Poles in the presence of German gendarmerie and the SS men of Einsatzgruppe B under Schaper set fire to a barn with over 300 Jews burned to death.[35]

There were also a number of criminal or opportunistic locals of various ethnicities,[41][42] known as szmalcownicy, who blackmailed the Jews in hiding and their Polish rescuers or turned them over to the Germans for financial gains. Official collaboration did not exist in Poland as it did in other countries such as France (see World War II collaboration and Poland for details). As Paulsson notes, "a single hooligan or blackmailer could wreak severe damage on Jews in hiding, but it took the silent passivity of a whole crowd to maintain their cover."[27]

The fact that the Polish Jewish community was decimated during World War II, coupled with well-known collaboration stories, has contributed to a stereotype of the Polish population having been passive in regard to, or even supportive of, Jewish suffering.[28][43] Also, the postwar portrayals of Holocaust perpetrators based on court testimonies greatly contribute to this multifaceted distortion in perspective, because the German policemen remained silent till the end about Polish help to Jews and their own brutal punishment for such help.[44]

Notable persons

|

|

See also

- Zofia Baniecka: With her mother, she rescued over 50 Jews in their Warsaw apartment between 1941–1944

- History of the Jews in 20th-century Poland

- Holocaust in Poland

- "Polish death camp" controversy

Notes

- ↑ "About the Righteous: Statistics". The Righteous Among The Nations. Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. 2013-01-01. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Richard C. Lukas, Out of the Inferno: Poles Remember the Holocaust University Press of Kentucky 1989 – 201 pages. Page 13; also in Richard C. Lukas, The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles Under German Occupation, 1939–1944, University Press of Kentucky 1986 – 300 pages.

- 1 2 3 Furth, Hans G. (1999). "One million Polish rescuers of hunted Jews?". Journal of Genocide Research 1 (2): 227–232. doi:10.1080/14623529908413952.

- 1 2 “Righteous Among the Nations” by country at Jewish Virtual Library

- 1 2 3 Holocaustforgotten Web site. Righteous of the World: Polish citizens killed while helping Jews During the Holocaust

- ↑ Gunnar S. Paulsson. Secret City. The Hidden Jews of Warsaw, 1940–1945. Yale University Press, 2002.

- 1 2 London Nakl. Stowarzyszenia Prawników Polskich w Zjednoczonym Królestwie [1941] ,Polska w liczbach. Poland in numbers. Zebrali i opracowali Jan Jankowski i Antoni Serafinski. Przedmowa zaopatrzyl Stanislaw Szurlej.

- ↑ Piper, Franciszek Piper. "The Number of Victims" in Gutman, Yisrael & Berenbaum, Michael. Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, Indiana University Press, 1994; this edition 1998, p. 62.

- ↑ Martin Gilbert. The Righteous: The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust. Macmillan, 2003. pp 101.

- ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1997). "Assistance to Jews". Poland's Holocaust. McFarland & Company. p. 117. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

- ↑ John T. Pawlikowski, Polish Catholics and the Jews during the Holocaust, in, Google Print, p. 113 in Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, Rutgers University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8135-3158-6

- ↑ Andrzej Sławiński, Those who helped Polish Jews during WWII. Translated from Polish by Antoni Bohdanowicz. Article on the pages of the London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Last accessed on 14 March 2008.

- ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1997). "Assistance to Jews". Poland's Holocaust. McFarland & Company. p. 118. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

- ↑ (Polish) Dariusz Libionka, "Polska ludność chrześcijańska wobec eksterminacji Żydów—dystrykt lubelski," in Dariusz Libionka, Akcja Reinhardt: Zagłada Żydów w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej–Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, 2004), p.325.

- 1 2 The Righteous and their world. Markowa through the lens of Józef Ulma, by Mateusz Szpytma, Institute of National Remembrance

- ↑ (Polish) Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Wystawa „Sprawiedliwi wśród Narodów Świata”– 15 czerwca 2004 r., Rzeszów. "Polacy pomagali Żydom podczas wojny, choć groziła za to kara śmierci – o tym wie większość z nas." (Exhibition "Righteous among the Nations." Rzeszów, 15 June 2004. Subtitled: "The Poles were helping Jews during the war – most of us already know that.") Last actualization 8 November 2008.

- ↑ (Polish) Jolanta Chodorska, ed., "Godni synowie naszej Ojczyzny: Świadectwa," Warsaw, Wydawnictwo Sióstr Loretanek, 2002, Part Two, pp.161–62. ISBN 83-7257-103-1

- ↑ Kalmen Wawryk, To Sobibor and Back: An Eyewitness Account (Montreal: The Concordia University Chair in Canadian Jewish Studies, and The Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies, 1999), pp.66–68, 71.

- ↑ Bartoszewski and Lewinówna, Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak, 1969, pp.533–34.

- ↑ Moroz and Datko, Męczennicy za wiarę 1939–1945, pp.385–86 and 390–91. Stanisław Łukomski, “Wspomnienia,” in Rozporządzenia urzędowe Łomżyńskiej Kurii Diecezjalnej, no. 5–7 (May–July) 1974: p.62; Witold Jemielity, “Martyrologium księży diecezji łomżyńskiej 1939–1945,” in Rozporządzenia urzędowe Łomżyńskiej Kurii Diecezjalnej, no. 8–9 (August–September) 1974: p.55; Jan Żaryn, “Przez pomyłkę: Ziemia łomżyńska w latach 1939–1945.” Conversation with Rev. Kazimierz Łupiński from Szumowo parish, Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej, no. 8–9 (September–October 2002): pp.112–17. In Mark Paul, Wartime Rescue of Jews. Page 252.

- ↑ Donald L. Niewyk, Francis R. Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust, Columbia University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-231-11200-9, Google Print, p.114

- ↑ Antony Polonsky, 'My Brother's Keeper?': Recent Polish Debates on the Holocaust, Routledge, 1990, ISBN 0-415-04232-1, Google Print, p.149

- ↑ Holocaust Survivors and Remembrance Project: Poland

- ↑ Robert D. Cherry, Annamaria Orla-Bukowska, Rethinking Poles and Jews: Troubled Past, Brighter Future, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, ISBN 0-7425-4666-7, Google Print, p.5

- ↑ Mordecai Paldiel, The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews, page 184. Published by KTAV Publishing House Inc.

- ↑ Iwo Pogonowski, Jews in Poland, Hippocrene, 1998. ISBN 0-7818-0604-6. Page 99.

- 1 2 Unveiling the Secret City H-Net Review: John Radzilowski

- 1 2 3 Gunnar S. Paulsson, "The Rescue of Jews by Non-Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland,” published in The Journal of Holocaust Education, volume 7, nos. 1 & 2 (summer/autumn 1998): pp.19–44. Reprinted in: "Collective Rescue Efforts of the Poles," p. 256. Quoted in: "Wartime Rescue of Jews by the Polish Catholic Clergy. The Testimony of Survivors," at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008) compiled by Mark Paul, with selected bibliography; the Polish Educational Foundation in North America, Toronto 2007

- ↑ Margaret Monahan Hogan, ed. (2011). "Remembering the Response of the Catholic Church" (PDF file, direct download 1.36 MB). History 1933 – 1948. What we choose to remember. University of Portland. pp. 85–97. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ John T. Pawlikowski. Polish Catholics and the Jews during the Holocaust. In: Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, Rutgers University Press, 2003.

- ↑ Wojciech Roszkowski (4 November 2008). "Historia: Godzina zero". Tygodnik.Onet.pl weekly. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ The Erwin and Riva Baker Memorial Collection (2001). Yad Vashem Studies. Wallstein Verlag. pp. 57–. ISSN 0084-3296.

- ↑ Jerzy Jan Lerski, Piotr Wróbel, Richard J. Kozicki, Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996, ISBN 0-313-26007-9, Google Print, 538

- ↑ Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski, "Jedwabne: The Politics of Apology", presented at the Panel Jedwabne – A Scientific Analysis, Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America, Inc., 8 June 2002, Georgetown University, Washington DC.

- 1 2 Tomasz Strzembosz, “Inny obraz sąsiadów” at the Wayback Machine (archived June 10, 2001)

- ↑ Christopher R. Browning, Jurgen Matthaus, The Origins of the Final Solution, page 262 Publisher University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8032-5979-4

- ↑ Michael C. Steinlauf. Bondage to the Dead. Syracuse University Press, p. 30.

- ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998), Poland's Holocaust. McFarland, page 209. ISBN 0786403713.

- ↑ Dr. Frank Grelka (2005). Ukrainischen Miliz. Die ukrainische Nationalbewegung unter deutscher Besatzungsherrschaft 1918 und 1941/42 (Viadrina European University: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag). pp. 283–284. ISBN 3447052597. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

RSHA von einer begrüßenswerten Aktivitat der ukrainischen Bevolkerung in den ersten Stunden nach dem Abzug der Sowjettruppen.

- ↑ Р. П. Шляхтич, ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х частинах Ін-т історії України НАН України (OUN in 1941: Documents in 2 volumes). Institute of History of Ukraine. Kiev: Ukraine National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 2006, pp. 426-427. ISBN 966-02-2535-0. Abstract, with links to PDF files.

- ↑ Emanuel Ringelblum, Joseph Kermish, Shmuel Krakowski, Polish-Jewish relations during the Second World War – Page 226 Quote from chapter "The Idealists": "Informing and denunciation flourish throughout the country, thanks largely to the Volksdeutsche. Arrests and round-ups at every step and constant searches..."

- ↑ Matthew J. Gibney, Randall Hansen, Immigration and Asylum, page 202. Quote: "[ethnic Ukrainians] assisted the German security police in arrests and executions of [..] Jewish civilians."

- ↑ Robert D. Cherry, Annamaria Orla-Bukowska, Rethinking Poles and Jews, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, ISBN 0-7425-4666-7, Google Print, p.25

- ↑ Christopher R. Browning (1998) [1992]. "Arrival in Poland" (PDF file, direct download 7.91 MB complete). Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Penguin Books. p. 158 (PDF, 185). Retrieved July 12, 2014.

Also: PDF cache archived by WebCite.

- 1 2 3 4 Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous" (a-v) at the Wayback Machine (archived March 1, 2008)

- ↑ W. Bartoszewski and Z. Lewinowna, Appeal by the Polish Underground Association For Aid to the Jews, Yad Vashem Remembrance Authority, 2004.

- ↑ Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous. Those Who Risked Their Lives" (b-v); Władysław Bartoszewski at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ Yad Vashem Remembrance Authority 2008, The Righteous: Anna Borkowska, Poland

- ↑ ""Saving Jews: Polish Righteous" (b-v): Banasiewicz family including Franciszek, Magdalena, Maria, Tadeusz and Jerzy". Web.archive.org. 6 February 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous. Those Who Risked Their Lives" (b-v); Bradlo family at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ Kystyna Danko, Poland; International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation

- ↑ Anna Poray, ibidem (d–v); Dobraczyński, Jan at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ About Maria Fedecka at www.mariafedecka.republika.pl, 2005

- ↑ Anna Poray, ibidem (f-v); Maria Fedecki at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008), 2004.

- ↑ Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous" (f-v); Mieczysław Fogg at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ Anna Poray, "Saving Jews" (g-v): Andrzej Garbuliński, Polish Righteous at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ The Righteous Among the Nations, Yad Vashem

- ↑ Mordecai Paldiel, "Churches and the Holocaust: unholy teaching, good samaritans, and reconciliation" p.209-210, KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 2006, ISBN 0-88125-908-X, ISBN 978-0-88125-908-7

- ↑ Cypora (Jablon) Zonszajn in Siedlce, Poland. Photo Archives, #71475. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Zofia Glazer. Retrieved 5 November 2015. The particulars of the story of rescue was confirmed using source in the Polish written by Jolanta Waśkiewicz in Warsaw.

- ↑ Sylwia Kesler, Halina and Julian Grobelny as Righteous Among the Nations

- ↑ Curtis M. Urness, Sr. & Terese Pencak Schwartz, Irene Gut Opdyke: She Hid Polish Jews Inside a German Officers' Villa, at Holocaust Forgotten.com

- ↑ Holocaust Memorial Center, 1988 – 2007, Opdyke, Irene; Righteous Gentile

- ↑ Anna Poray, ibidem (w-v); Henryk Iwanski alias Bystry, at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008) Armia Krajowa mayor.

- ↑ Stefan Jagodzinski at the www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- ↑ Anna Poray, ibidem (cover page) at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ Poles Honoured by Israel, Warsaw Life news agency

- ↑ Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous. Those Who Risked Their Lives" (k-v); Aleksander Kamiński at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ Michael T. Kaufman, Jan Karski warns the West about Holocaust, The New York Times, 15 July 2000

- ↑ Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous. Those Who Risked Their Lives" (k-v); Jan Karski at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ Yad Vashem Remembrance Authority, The Tree in Honor of Zegota, 2008

- ↑ "Maria Kotarba at www.auschwitz.org.pl" (PDF). Auschwitz.org.pl. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2008, The Righteous Among the Nations, 28 June 2003

- ↑ Peggy Curran, "Pole to be honoured for sheltering Jews from Gestapo," Reprinted by the Canadian Foundation of Polish-Jewish Heritage, Montreal Chapter. Station Cote St.Luc, C. 284, Montreal QC, Canada H4V 2Y4. First published: Montreal Gazette, 5 August 2003, and: Montreal Gazette, 10 December 1994.

- ↑ "Jerzy Jan Lerski. Short bio based on biography featured in ''Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945''". Web.ku.edu. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ March of the Living International, The Warsaw Ghetto

- ↑ Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous. Those Who Risked Their Lives" (a-v): Igor Newerly at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ ""Saving Jews: Polish Righteous" (n-v); Wacław Nowiński". Web.archive.org. 6 February 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ David M. Crowe, The Holocaust: Roots, History, and Aftermath. Published by Westview Press. Page 180.

- ↑ Wartime Rescue of Jews, edited and compiled by Mark Paul at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008) Polish Educational Foundation in North America, Toronto 2007. "Collective Rescue Efforts of the Poles", (pdf file: 1.44 MB).

- ↑ Stefania and her younger sister Helena Podgorska, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C., 2008

- ↑ Anna Poray, (ibidem, p-v) Three Puchalski families: Jan Puchalski (1879–1946), Anna (1894–1994), and Stanisław (1920–2000), the Polish Righteous at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ www.mateusz.pl – interview with Konrad Rudnicki (Polish)

- ↑ Polish righteous: Rodzina Szczygłów (Szczygieł family), with daughter Joanna Załucka. Museum of the History of Polish Jews. (Polish) (English) Also in: 1). "Jewish Holocaust Survivor Is Reunited with Her Christian Rescuer For First Time Since 1944," Rugged Elegance. 2). Yiddishe Mamas: The Truth About the Jewish Mother, Marnie Winston-Macauley, pp. 299–300, Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2007, ISBN 0-7407-6376-8

- ↑ Monika Scislowska, Associated Press, 12 May 2008, "Irena Sendler, Holocaust hero dies at 98". Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ Grzegorz Łubczyk, FKCh "ZNAK" 1999–2008, Henryk Slawik – Our Raoul Wallenberg, Trybuna 120 (3717), 24 May 2002, p. Aneks 204, p. A, F.

- ↑ Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, „Sprawiedliwi wśród Narodów Świata” – Warszawa, 7 stycznia 2004

- ↑ Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous" (t-v); Józef Tkaczyk at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ "Sunday – Catholic Magazine". Sunday.niedziela.pl. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ↑ FKCh "ZNAK" – 1999–2008, Righteous from Wroclaw (incl. Professor Rudolf Wiegl) at the Wayback Machine (archived March 25, 2007) 24 July 2003, from the Internet Archive

- ↑ Anna Poray, ibidem (w-v); Henryk Wolinski alias Waclaw at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

- ↑ Anna Poray, ibidem (z-v); Zagorski Jerzy & Maria at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008). 2004

- ↑ Yad Vashem Remembrance Authority, 2008, Hiding in Zoo Cages; Jan & Antonina Zabinski, Poland

- ↑ Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous" (z-v); Jan & Antonina Zabinski, Poland at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008)

External links

- Polish Righteous at Museum of The History of Polish Jews

- Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous. Those Who Risked Their Lives," at the Wayback Machine (archived February 6, 2008) with photographs and bibliography, 2004. List of Poles recognized as "Righteous among the Nations" by Israel's Yad Vashem (31 December 1999), with 5,400 awards including 704 of those who paid with their lives for saving Jews.

- (Polish) Piotr Zychowicz, Do Izraela z bohaterami: Wystawa pod Tel Awiwem pokaże, jak Polacy ratowali Żydów, Rp.pl, 18 November 2009

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||