Riesz function

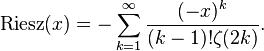

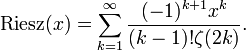

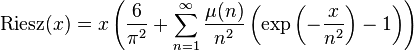

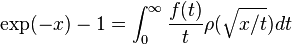

In mathematics, the Riesz function is an entire function defined by Marcel Riesz in connection with the Riemann hypothesis, by means of the power series

If we set  we may define it in terms of the coefficients of the Laurent series development of the hyperbolic (or equivalently, the ordinary) cotangent around zero. If

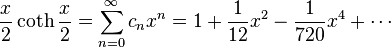

we may define it in terms of the coefficients of the Laurent series development of the hyperbolic (or equivalently, the ordinary) cotangent around zero. If

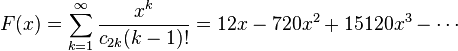

then F may be defined as

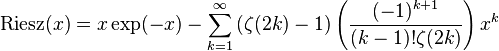

The values of ζ(2k) approach one for increasing k, and comparing the series for the Riesz function with that for  shows that it defines an entire function. Alternatively, F may be defined as

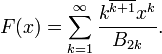

shows that it defines an entire function. Alternatively, F may be defined as

denotes the rising factorial power in the notation of D. E. Knuth and the number Bn are the Bernoulli number. The series is one of alternating terms and the function quickly tends to minus infinity for increasingly negative values of x. Positive values of x are more interesting and delicate.

denotes the rising factorial power in the notation of D. E. Knuth and the number Bn are the Bernoulli number. The series is one of alternating terms and the function quickly tends to minus infinity for increasingly negative values of x. Positive values of x are more interesting and delicate.

Riesz criterion

It can be shown that

for any exponent e larger than 1/2, where this is big O notation; taking values both positive and negative. Riesz showed that the Riemann hypothesis is equivalent to the claim that the above is true for any e larger than 1/4.[1] In the same paper, he added a slightly pessimistic note too: «Je ne sais pas encore decider si cette condition facilitera la vérification de l'hypothèse».

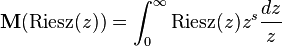

Mellin transform of the Riesz function

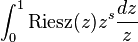

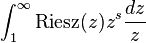

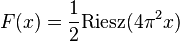

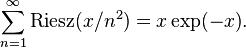

The Riesz function is related to the Riemann zeta function via its Mellin transform. If we take

we see that if  then

then

converges, whereas from the growth condition we have that if

then

then

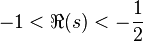

converges. Putting this together, we see the Mellin transform of the Riesz function is defined on the strip  .

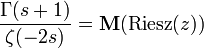

On this strip, we have

.

On this strip, we have

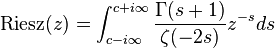

From the inverse Mellin transform, we now get an expression for the Riesz function, as

where c is between minus one and minus one-half. If the Riemann hypothesis is true, we can move the line of integration to any value less than minus one-fourth, and hence we get the equivalence between the fourth-root rate of growth for the Riesz function and the Riemann hypothesis.

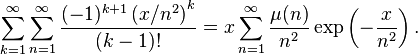

J. garcia (see references) gave the integral representation of  using Borel resummation as

using Borel resummation as

and

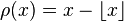

and  is the fractional part of 'x'

is the fractional part of 'x'

Calculation of the Riesz function

The Maclaurin series coefficients of F increase in absolute value until they reach their maximum at the 40th term of -1.753×1017. By the 109th term they have dropped below one in absolute value. Taking the first 1000 terms suffices to give a very accurate value for

for

for  . However, this would require evaluating a polynomial of degree 1000 either using rational arithmetic with the coefficients of large numerator or denominator, or using floating point computations of over 100 digits. An alternative is to use the inverse Mellin transform defined above and numerically integrate. Neither approach is computationally easy.

. However, this would require evaluating a polynomial of degree 1000 either using rational arithmetic with the coefficients of large numerator or denominator, or using floating point computations of over 100 digits. An alternative is to use the inverse Mellin transform defined above and numerically integrate. Neither approach is computationally easy.

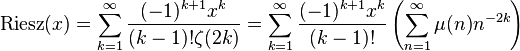

Another approach is to use acceleration of convergence. We have

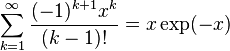

Since ζ(2k) approaches one as k grows larger, the terms of this series approach

. Indeed, Riesz noted that:

. Indeed, Riesz noted that:

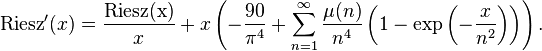

Using Kummer's method for accelerating convergence gives

with an improved rate of convergence.

Continuing this process leads to a new series for the Riesz function with much better convergence properties:

Here μ is the Möbius mu function, and the rearrangement of terms is justified by absolute convergence. We may now apply Kummer's method again, and write

the terms of which eventually decrease as the inverse fourth power of n.

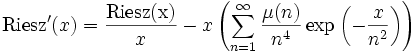

The above series are absolutely convergent everywhere, and hence may be differentiated term by term, leading to the following expression for the derivative of the Riesz function:

which may be rearranged as

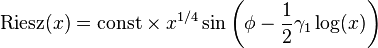

Marek Wolf in[2] assuming the Riemann Hypothesis has shown that for large x:

where  is the imaginary part

of the first nontrivial zero of the zeta function,

is the imaginary part

of the first nontrivial zero of the zeta function,  and

and  . It agrees with the general theorems

about zeros of the Riesz function proved in 1964 by Herbert Wilf.[3]

. It agrees with the general theorems

about zeros of the Riesz function proved in 1964 by Herbert Wilf.[3]

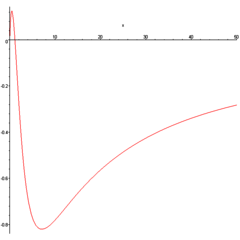

Appearance of the Riesz function

A plot for the range 0 to 50 is given above. So far as it goes, it does not indicate very rapid growth and perhaps bodes well for the truth of the Riemann hypothesis.

Notes

- ↑ M. Riesz, «Sur l'hypothèse de Riemann», Acta Mathematica, 40 (1916), pp.185-90.». For English translation look here

- ↑ M. Wolf, "Evidence in favor of the Baez-Duarte criterion for the Riemann Hypothesis", Computational Methods in Science and Technology, v.14 (2008) pp.47-54

- ↑ H.Wilf, " On the zeros of Riesz' function in the analytic theory of numbers", Illinois J. Math., 8 (1964), pp. 639-641

References

- Titchmarsh, E. C., The Theory of the Riemann Zeta Function, second revised (Heath-Brown) edition, Oxford University Press, 1986, [Section 14.32]