Riemann curvature tensor

| General relativity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|

Fundamental concepts |

||||||

|

||||||

In the mathematical field of differential geometry, the Riemann curvature tensor or Riemann–Christoffel tensor (after Bernhard Riemann and Elwin Bruno Christoffel) is the most common method used to express the curvature of Riemannian manifolds. It associates a tensor to each point of a Riemannian manifold (i.e., it is a tensor field), that measures the extent to which the metric tensor is not locally isometric to that of Euclidean space. The curvature tensor can also be defined for any pseudo-Riemannian manifold, or indeed any manifold equipped with an affine connection.

It is a central mathematical tool in the theory of general relativity, the modern theory of gravity, and the curvature of spacetime is in principle observable via the geodesic deviation equation. The curvature tensor represents the tidal force experienced by a rigid body moving along a geodesic in a sense made precise by the Jacobi equation.

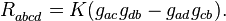

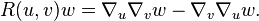

The curvature tensor is given in terms of the Levi-Civita connection  by the following formula:

by the following formula:

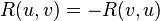

where [u,v] is the Lie bracket of vector fields. For each pair of tangent vectors u, v, R(u,v) is a linear transformation of the tangent space of the manifold. It is linear in u and v, and so defines a tensor. Occasionally, the curvature tensor is defined with the opposite sign.

If  and

and  are coordinate vector fields then

are coordinate vector fields then ![[u,v]=0](../I/m/7e1a8512f323229a42f899d06f32992c.png) and therefore the formula simplifies to

and therefore the formula simplifies to

The curvature tensor measures noncommutativity of the covariant derivative, and as such is the integrability obstruction for the existence of an isometry with Euclidean space (called, in this context, flat space). The linear transformation  is also called the curvature transformation or endomorphism.

is also called the curvature transformation or endomorphism.

The curvature formula can also be expressed in terms of the second covariant derivative defined as:[1]

which is linear in u and v. Then:

Thus in the general case of non-coordinate vectors u and v, the curvature tensor measures the noncommutativity of the second covariant derivative.

Geometrical meaning

Informally

Imagine walking around the bounding white line of a tennis court with a stick held out in front of you. When you reach the first corner of the court, you turn to follow the white line, but you keep the stick held out in the same direction, which means you are now holding the stick out to your side. You do the same when you reach each corner of the court. When you get back to where you started, you are holding the stick out in exactly the same direction as you were when you started (no surprise there).

Now imagine you are standing on the equator of the earth, facing north with the stick held out in front of you. You walk north up along a line of longitude until you get to the north pole. At that point you turn right, ninety degrees, but you keep the stick held out in the same direction, which means you are now holding the stick out to your left. You keep walking until you get to the equator. There, you turn right again (and so now you have to hold the stick pointing out behind you) and walk along the equator until you get back to where you started from. But here is the thing: the stick is pointing back along the equator from where you just came, not north up to the pole how it was when you started!

The reason for the difference is that the surface of the earth is curved, whereas the surface of a tennis court is flat, but it is not quite that simple. Imagine that the tennis court is slightly humped along its centre-line so that it is like part of the surface of a cylinder. If you walk around the court again, the stick still points in the same direction as it did when you started. This is a consequence of that the tennis court still has zero Gaussian curvature (such as for the surface of a sheet of paper that is bent but not stretched) and the Gauss–Bonnet theorem.

The Riemann curvature tensor is a way to capture a measure of the intrinsic curvature. When you write it down in terms of its components (like writing down the components of a vector), it consists of a multi-dimensional array of sums and products of partial derivatives (some of those partial derivatives can be thought of as akin to capturing the curvature imposed upon someone walking in straight lines on a curved surface).

Formally

When a vector in a Euclidean space is parallel transported around a loop, it will again point in the initial direction after returning to its original position. However, this property does not hold in the general case. The Riemann curvature tensor directly measures the failure of this in a general Riemannian manifold. This failure is known as the non-holonomy of the manifold.

Let xt be a curve in a Riemannian manifold M. Denote by τxt : Tx0M → TxtM the parallel transport map along xt. The parallel transport maps are related to the covariant derivative by

for each vector field Y defined along the curve.

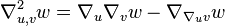

Suppose that X and Y are a pair of commuting vector fields. Each of these fields generates a one-parameter group of diffeomorphisms in a neighborhood of x0. Denote by τtX and τtY, respectively, the parallel transports along the flows of X and Y for time t. Parallel transport of a vector Z ∈ Tx0M around the quadrilateral with sides tY, sX, −tY, −sX is given by

This measures the failure of parallel transport to return Z to its original position in the tangent space Tx0M. Shrinking the loop by sending s, t → 0 gives the infinitesimal description of this deviation:

where R is the Riemann curvature tensor.

Coordinate expression

Converting to the tensor index notation, the Riemann curvature tensor is given by

where  are the coordinate vector fields. The above expression can be written using Christoffel symbols:

are the coordinate vector fields. The above expression can be written using Christoffel symbols:

(see also the list of formulas in Riemannian geometry).

The Riemann curvature tensor is also the commutator of the covariant derivative of an arbitrary covector  with itself:[2][3]

with itself:[2][3]

since the connection  is torsionless, which means that the torsion tensor

is torsionless, which means that the torsion tensor  vanishes.

vanishes.

This formula is often called the Ricci identity.[4] This is the classical method used by Ricci and Levi-Civita to obtain an expression for the Riemann curvature tensor.[5] In this way, the tensor character of the set of quantities  is proved.

is proved.

This identity can be generalized to get the commutators for two covariant derivatives of arbitrary tensors as follows

This formula also applies to tensor densities without alteration, because for the Levi-Civita (not generic) connection one gets:[4]

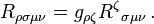

It is sometimes convenient to also define the purely covariant version by

Symmetries and identities

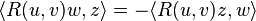

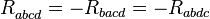

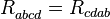

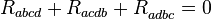

The Riemann curvature tensor has the following symmetries:

Here the bracket  refers to the inner product on the tangent space induced by the metric tensor. The last identity was discovered by Ricci, but is often called the first Bianchi identity or algebraic Bianchi identity, because it looks similar to the Bianchi identity below. (Also, if there is nonzero torsion, the first Bianchi identity becomes a differential identity of the torsion tensor.)

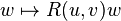

These three identities form a complete list of symmetries of the curvature tensor, i.e. given any tensor which satisfies the identities above, one can find a Riemannian manifold with such a curvature tensor at some point. Simple calculations show that such a tensor has

refers to the inner product on the tangent space induced by the metric tensor. The last identity was discovered by Ricci, but is often called the first Bianchi identity or algebraic Bianchi identity, because it looks similar to the Bianchi identity below. (Also, if there is nonzero torsion, the first Bianchi identity becomes a differential identity of the torsion tensor.)

These three identities form a complete list of symmetries of the curvature tensor, i.e. given any tensor which satisfies the identities above, one can find a Riemannian manifold with such a curvature tensor at some point. Simple calculations show that such a tensor has  independent components.

independent components.

Yet another useful identity follows from these three:

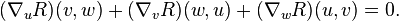

On a Riemannian manifold one has the covariant derivative  and the Bianchi identity (often called the second Bianchi identity or differential Bianchi identity) takes the form:

and the Bianchi identity (often called the second Bianchi identity or differential Bianchi identity) takes the form:

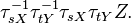

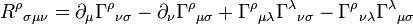

Given any coordinate chart about some point on the manifold, the above identities may be written in terms of the components of the Riemann tensor at this point as:

- Skew symmetry

- Interchange symmetry

- First Bianchi identity

- This is often written

- where the brackets denote the antisymmetric part on the indicated indices. This is equivalent to the previous version of the identity because the Riemann tensor is already skew on its last two indices.

- Second Bianchi identity

- The semi-colon denotes a covariant derivative. Equivalently,

- again using the antisymmetry on the last two indices of R.

The algebraic symmetries are also equivalent to saying that R belongs to the image of the Young symmetrizer corresponding to the partition 2+2.

Special cases

- Surfaces

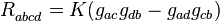

For a two-dimensional surface, the Bianchi identities imply that the Riemann tensor can be expressed as

where  is the metric tensor and

is the metric tensor and  is a function called the Gaussian curvature and a, b, c and d take values either 1 or 2. The Riemann tensor has only one functionally independent component. The Gaussian curvature coincides with the sectional curvature of the surface. It is also exactly half the scalar curvature of the 2-manifold, while the Ricci curvature tensor of the surface is simply given by

is a function called the Gaussian curvature and a, b, c and d take values either 1 or 2. The Riemann tensor has only one functionally independent component. The Gaussian curvature coincides with the sectional curvature of the surface. It is also exactly half the scalar curvature of the 2-manifold, while the Ricci curvature tensor of the surface is simply given by

- Space forms

A Riemannian manifold is a space form if its sectional curvature is equal to a constant K. The Riemann tensor of a space form is given by

Conversely, except in dimension 2, if the curvature of a Riemannian manifold has this form for some function K, then the Bianchi identities imply that K is constant and thus that the manifold is (locally) a space form.

See also

- Introduction to mathematics of general relativity

- Decomposition of the Riemann curvature tensor

- Curvature of Riemannian manifolds

Notes

- ↑ Lawson, H. Blaine, Jr.; Michelsohn, Marie-Louise (1989). Spin Geometry. Princeton U Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-691-08542-0.

- ↑ Synge J.L., Schild A. (1949). Tensor Calculus. first Dover Publications 1978 edition. pp. 83; 107. ISBN 978-0-486-63612-2.

- ↑ P. A. M. Dirac (1996). General Theory of Relativity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01146-X.

- 1 2 Lovelock, David; Rund, Hanno (1989) [1975]. Tensors, Differential Forms, and Variational Principles. Dover. p. 84,109. ISBN 978-0-486-65840-7.

- ↑ Ricci, Gregorio; Levi-Civita, Tullio (March 1900), "Méthodes de calcul différentiel absolu et leurs applications" (PDF), Mathematische Annalen (Springer) 54 (1–2): 125–201, doi:10.1007/BF01454201

References

- Besse, A.L. (1987), Einstein manifolds, Springer

- Kobayashi, S.; Nomizu, K. (1963), Foundations of differential geometry, vol. 1, Interscience

- Misner, Charles W.; Thorne, Kip S.; Wheeler, John A. (1973), Gravitation, W. H. Freeman, ISBN 0-7167-0344-0

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![R(u,v)w=\nabla_u\nabla_v w - \nabla_v \nabla_u w - \nabla_{[u,v]} w](../I/m/d1aa621fc7af204a1dc4a2a247129ad5.png)

![\left.\frac{d}{ds}\frac{d}{dt}\tau_{sX}^{-1}\tau_{tY}^{-1}\tau_{sX}\tau_{tY}Z\right|_{s=t=0} = (\nabla_X\nabla_Y - \nabla_Y\nabla_X - \nabla_{[X,Y]})Z = R(X,Y)Z](../I/m/29dde1c5fbbdf767ba683c40e3b6ebee.png)

![R_{a[bcd]}^{}=0,](../I/m/d521c7a46d666647116f179ca8fc3023.png)

![R_{ab[cd;e]}^{}=0](../I/m/cbab855528513cf1e7bb0a0a6096c158.png)