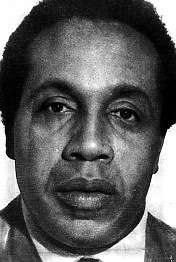

Richie Roberts

| Richard M. Roberts | |

|---|---|

| Born |

November 28, 1937 Bronx, New York, United States |

| Nationality | U.S.-American |

| Occupation |

Criminal Defense Attorney (1975-2015) former Detective (1963-1971), former Assistant Prosecutor (1971-1975), former Head of Narcotics Task Force, Federal Bureau of Narcotics (1973-1975), |

| Known for | Prosecution of drug kingpin Frank Lucas |

Richard M. "Richie" Roberts (born March 17, 1937) is an American defense attorney licensed to practice law in the state of New Jersey. Roberts was a former law enforcement officer who worked as a detective in the Essex County Prosecutor's Office and Federal Bureau of Narcotics. After completing a law degree at Seton Hall University and passing the bar examination, Roberts served as an Assistant Prosecutor in the Essex County Prosecutor's Office.

Roberts is recognized for his role in the investigation, arrest, and prosecution of Harlem "drug kingpin" Frank Lucas, who operated a heroin smuggling and distribution ring in the New York City neighborhood. In addition to bringing down Lucas's operation, Roberts's investigation also uncovered police corruption connected with the drug trade . Lucas's criminal enterprise and the investigation by Roberts was the subject of the 2007 film American Gangster starring actor Denzel Washington (as Lucas) and Australian actor Russell Crowe (as Roberts). After Lucas was incarcerated, Roberts entered private practice as an attorney specializing in criminal defense, and was retained by Lucas as defense counsel.

Biography

Life and career

Roberts was born in the Bronx, in New York City on November 28, 1937. His family was Jewish. Roberts was raised by his grandparents in the Bronx until he moved to Newark, New Jersey with his parents when he was eight years old. He graduated from Newark's Weequahic High School, where he was a star football and baseball player.[1]

After high school, Roberts served for six years in the United States Marine Corps and attained the rank of Sergeant before being discharged from the service in 1961.[1] He attended Upsala College (now defunct) in East Orange, New Jersey, but failed during his senior year as a result of poor attendance.[1] Roberts later completed his undergraduate work at Rutgers University.

In 1963, Roberts was employed as a Detective by the Essex County Prosecutor's Office in Essex County, New Jersey where for several years he was involved in undercover organized crime investigations.[1] Attending night classes, he received a Juris Doctor degree from Seton Hall University School of Law and passed the Bar Examination in New Jersey in August 1971.[1] After being licensed as an attorney, Roberts was made an Assistant Prosecutor in the Essex County Prosecutor's Office. Shortly after, he was tapped to head a special Narcotics Task Force overseen by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.[1] Roberts remained with the prosecutor's office until 1975.[2]

After working as a prosecutor for over 10 years, Roberts became a criminal defense attorney in 1981.[3] After leaving the prosecutor's office, Roberts was briefly affiliated with the firm of Harkavy, Goldman & Caprio, but soon established his own firm.[1] As of 2012, Roberts still works in the area of criminal defense. The first person he defended was Frank Lucas.[4] During private practice, Roberts has defended many homicide cases and was involved in New Jersey's first Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) case.[3] He has also been a guest speaker to conferences held by several police and private groups.[3] He was a co-managing partner of Roberts-Saluti, LLC a Criminal & Civil Litigation firm with offices in Newark, New Jersey, however partner Gerald M. Saluti,Jr., has been suspended from the practice of law as of February 28, 2014. See, http://drblookupportal.judiciary.state.nj.us/SearchResults.aspx?type=search (with partner Gerald M. Saluti, Esq.)[3] Mr. Roberts is the subject of numerous lawsuits and Judgments and Liens in excess of $850,000.00 See, https://njcourts.judiciary.state.nj.us/web15/JudgmentWeb/jsp/judgmentCaptcha.faces & http://njcourts.judiciary.state.nj.us/web15z/ACMSPA/ Mr. Roberts is the subject of numerous Disciplinary Review Board decisions. See, http://drblookupportal.judiciary.state.nj.us/SearchResults.aspx?type=search. Richard M. Roberts was suspended from the practice of law indefinitely on November 24, 2015 for failing to pay a New Jersey Supreme Court Fee Arbitration Award. On December 4, 2015 he was suspended from the practice of law for a second time for 3-months. See, http://drblookupportal.judiciary.state.nj.us/SearchResults.aspx?type=docket_no&docket_no=14-345.

Investigating Frank Lucas and "Blue Magic"

As the head of a Federal Bureau of Narcotics task force, Roberts is best known for his role in the investigation, arrest, and prosecution of Frank Lucas (b. 1930), an African-American drug kingpin who operated a heroin smuggling and distribution ring from Harlem in New York City in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This legacy is bolstered by the recent film American Gangster, however crime historian Ron Chepesiuk states that Roberts "was a minor figure in the Lucas investigation; the idea that Roberts was the key official in bringing Lucas down is Hollywood's imagination."[5] Even Roberts has stated that his character in the film is more of a composite of several investigators' work and not an accurate portrayal of him.[6]

Lucas was a petty criminal until he became associated with Harlem crime lord Ellsworth "Bumpy" Johnson (1905-1968).[7] After Johnson's death, Lucas sought advancement by bypassing the Italian Mafia's control of the New York City heroin trade and obtained his heroin direct from Asia's Golden Triangle, often travelling to Bangkok, Thailand and utilizing military personnel to transport narcotics. Lucas frequently boasted that he smuggled heroin back to the United States using the coffins of American servicemen killed in the Vietnam War.[6][7] However, this claim has been denied by his associate in Southeast Asia, Leslie "Ike" Atkinson (who was nicknamed "Sergeant Smack" by the Drug Enforcement Administration investigators). Atkinson claimed that the drugs were transported in furniture as well as the coffins. However, not in with the bodies, but in holed out portions on the bottom.[8][9]

Lucas, and his associates (largely drawn from family and close friends), sold heroin under the name "Blue Magic", and claimed that it was 98-100% pure when shipped from Thailand.[7][10] However, it was cut with mannite and quinine and resulted in a final product that was only 10 percent pure when it hit the streets.[7] However, this was much better than the rival "brands," which were lucky to be at 5 percent purity and likely less.[7] By bypassing the trafficking middlemen, using innovative shipping, and providing a higher quality product, Lucas was able to dominate the market through the sale of heroin at inexpensive prices.. Lucas claimed that he earned US$ 1 million a day selling heroin from his base of operations on 116th Street in Manhattan, although this was later believed to be an exaggeration.[7][10] Interestingly enough, Roberts disclosed on the WBGO 88.3 public radio program, Conversations With Allan Wolper that heroin dealers in New York area were claiming their drugs were "Blue Magic," hoping to take advantage of the publicity generated by American Gangster.[11]

In January 1975, Lucas's residence in Teaneck, New Jersey was raided by a task force consisting of agents from Group 22 of the federal Drug Enforcement Administration and detectives from New York Police Department's Organized Crime Control Bureau (OCCB).[12] In 1976, Lucas was convicted of drug trafficking and distribution offenses and sentenced to 70 years in prison (a consecutive 40-year federal prison sentence and 30-year New Jersey state prison sentence).[13] After cooperation in the prosecution of over 100 other drug-related cases, Lucas was offered placement in the federal witness protection program, and in 1981 after 5 years in prison custody, his sentence was reduced to "time served" with lifetime parole supervision.[13] After violating parole with a minor drug distribution offense, Lucas (who was defended by Roberts) was returned to prison and was released in 1991.[14][15]

Depictions in Media

The story of Roberts' investigation and prosecution of Frank Lucas was adapted into the 2007 film American Gangster, starring Academy Award-winning actors Denzel Washington portraying Lucas and Russell Crowe portraying Roberts. The film grossed more than US$127 million[16] and was met with generally positive reviews.[17] However, several persons involved with the actual events regarding the investigation and prosecution (including Lucas and Roberts) have criticized the film as a largely fictional and exaggerated portrayal that contained inaccuracies and fabrication.[18]

The film portrays Roberts as being mired in a personal child custody battle and that this aspect of his personal life was compromised by his dogged investigation of Lucas. This was entirely fabricated as Roberts never had a child.[18] Roberts also criticized the portrayal of Lucas by describing it as "almost noble".[18]

Comparatively, Sterling Johnson, Jr., a federal judge who served as a special narcotics prosecutor and assisted the arrest and trial of Lucas, described the film as "one percent reality and ninety-nine percent Hollywood." In addition, Johnson described the real life Lucas as "illiterate, vicious, violent, and everything Denzel Washington was not."[19] Former Drug Enforcement Administration agents filed a lawsuit against Universal Studios saying that the events in the film were fictionalized and that the film defamed them and hundreds of other agents.[20]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Waldron, Mary. "American Hero: Richard Richie Roberts". Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ↑ Jones, Richard G. "A New Jersey Crime Story’s Hollywood Ending", The New York Times (1 November 2007). Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Roberts-Saluti Attorneys at Law - Our Team. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ↑ William Kleinknecht, From Foes to Friends and Now on to Fame, The Star-Ledger, October 5, 2006.

- ↑ Chepesiuk, Ron. Superfly: The True, Untold Story of Frank Lucas, American Gangster.

- 1 2 American Gangster True Story - The real Frank Lucas, Richie Roberts. Chasingthefrog.com. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Return of Superfly" New York Magazine, 14 August 2000.

- ↑ Cable News Network (CNN). "Is 'American Gangster' really all that 'true'?" 22 January 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008. (Archived March 3, 2008 at the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ Chepesiuk, Ron. "New Criminologist Special - Frank Lucas, 'American Gangster,' and the Truth Behind the Asian Connection". 17 January 2008.

- 1 2 Jacobson, Mark. "A Conversation Between Frank Lucas and Nicky Barnes". New York Magazine 25 October 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ↑ "Richie Roberts Describes His Life That Is Portrayed In American Gangster" 16 November 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2014

- ↑ Chepesiuk, Ron and Gonzalez, Anthony."The Raid in Teaneck" in Crime Magazine (2007).

- 1 2 "U.S. Jury Convicts Heroin Informant". The New York Times. 25 August 1984.

- ↑ "Drug Dealer Gets New Prison Term". The New York Times. 11 September 1984.

- ↑ Oswald, Janelle. "The Real American Gangster". The Voice. 9 December 2007.

- ↑ ABC News, Reuters. "American Gangster lawsuit dismissed" 18 February 2008.

- ↑ "American Gangster". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- 1 2 3 Susannah Cahalan. ""Ganging Up on Movie's 'Lies'". The New York Post (4 November 2007). Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ↑ Coyle, Jake. "Is 'American Gangster' really all that 'true'?". Toronto Star. (17 January 2008).

- ↑ WPRI. "DEA agents sue over 'American Gangster'". 8 February 2008.

Further reading

- Interview by Charlie Rose of Frank Lucas, Ritchie Roberts and others

- Article about Richie Roberts at lawcrossing.com (engl.)

- Unlikely friendship piques Hollywood interest

- A New Jersey Crime Story’s

http://drblookupportal.judiciary.state.nj.us/SearchResults.aspx?type=docket_no&docket_no=14-345