Milk shark

| Milk shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Superorder: | Selachimorpha |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Rhizoprionodon |

| Species: | R. acutus |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhizoprionodon acutus (Rüppell, 1837) | |

| |

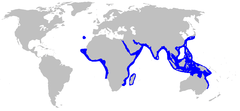

| Range of the milk shark | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Carcharias aaronis Hemprich & Ehrenberg, 1899 | |

The milk shark (Rhizoprionodon acutus) is a species of requiem shark, and part of the family Carcharhinidae, whose common name comes from an Indian belief that consumption of its meat promotes lactation. The largest and most widely distributed member of its genus, the milk shark typically measures 1.1 m (3.6 ft) long, and can be found in coastal tropical waters throughout the eastern Atlantic and the Indo-Pacific regions. Occurring from the surface to a depth of 200 m (660 ft), this species is common near beaches and in estuaries, and has been recorded swimming up rivers in Cambodia. Juveniles are known to inhabit tidal pools and seagrass meadows. The milk shark has a slender body with a long, pointed snout and large eyes, and is a nondescript gray above and white below. This shark can be distinguished from similar species in its range by the long furrows at the corners of its mouth, and seven to 15 enlarged pores just above them.

Among the most abundant sharks within its range, the milk shark feeds primarily on small bony fishes, but also takes cephalopods and crustaceans. In turn, it often falls prey to larger sharks and possibly marine mammals. In common with other members of its family, this species is viviparous, with the developing embryos sustained by a placental connection. Females give birth to one to eight young either during a defined breeding season or throughout the year, depending on location. The reproductive cycle is usually annual, but may be biennial or triennial. Large numbers of milk sharks are caught by artisanal and commercial fisheries in many countries for meat, fins, and fishmeal. Despite this, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed this species as being of Least Concern, because its wide distribution and relatively high productivity seemingly allow present levels of exploitation to be sustained.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The German naturalist Eduard Rüppell published the first scientific description of the milk shark, as Carcharias acutus (the specific epithet means "sharp" in Latin), in his 1837 Fische des Rothen Meeres (Fishes of the Red Sea). It has since been listed under several different genera, including Carcharhinus and Scoliodon, before finally being placed in the genus Rhizoprionodon via synonymization with the type species, R. crenidens.[2][3] As Rüppell did not mention a type specimen, in 1960, Wolfgang Klausewitz designated a 44 cm (17 in)-long male caught off Jeddah, Saudi Arabia as the lectotype for this species.[2]

The common name "milk shark" comes from a belief held in India that eating this shark's meat enhances lactation.[3] Other names for this species include fish shark, grey dog shark, little blue shark, Longmans dogshark, milk dog shark, sharp-nosed (milk) shark, Walbeehm's sharp-nosed shark, and white-eye shark.[4] A 1992 phylogenetic analysis by Gavin Naylor, based on allozymes, found that the milk shark is the most basal of the four Rhizoprionodon species examined.[5] The extinct R. fischeuri, known from Middle Miocene (16–12 Ma) deposits in southern France and Portugal, may be the same as R. acutus.[6]

Distribution and habitat

The milk shark has the widest distribution of any Rhizoprionodon species.[1] In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, it is found from Mauritania to Angola, as well as around Madeira and in the Gulf of Taranto off southern Italy.[7] In the Indian Ocean, it occurs from South Africa and Madagascar northward to the Arabian Peninsula, and eastward to South and Southeast Asia. In the Pacific Ocean, this species occurs from China and southern Japan, through the Philippines and Indonesia, to New Guinea and northern Australia.[2] The milk shark likely once had a contiguous distribution by way of the Tethys Sea, until during the Miocene epoch, when eastern Atlantic sharks were isolated from Indo-Pacific sharks by the collision of Asia and Africa.[6]

Occurring close to shore from the surf zone to a depth of 200 m (660 ft), the milk shark favors turbid water off sandy beaches and occasionally enters estuaries.[2][8] In Shark Bay, Western Australia, juvenile milk sharks inhabit seagrass meadows composed of Amphibolis antarctica and Posidonia australis.[9] Although some sources state this species avoids low salinities,[2][3] it has been reported several times from fresh water in Cambodia, as far upstream as the Tonlé Sap.[10] Milk sharks may be found anywhere in the water column from the surface to the bottom.[11] Off KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, its numbers fluctuate annually with a peak in summer, suggesting some form of seasonal movement.[3]

Description

The largest member of its genus, off West Africa the milk shark has been reported to reach 1.78 m (5.8 ft) and 22 kg (49 lb) for males, and 1.65 m (5.4 ft) and 17 kg (37 lb) for females,[12] though there is uncertainty regarding the species identity of these specimens.[4] Even if accepted, these figures are considered exceptional and most individuals do not exceed 1.1 m (3.6 ft) in length.[2] Generally, females are heavier and attain a greater maximum size than males.[13]

The milk shark has a slender build with a long, pointed snout, large, round eyes with nictitating membranes (protective third eyelids), and no spiracles. On each side of the head behind the corner of the jaw, there are usually seven to 15 enlarged pores. The nostrils are small, as are the adjacent triangular skin flaps. There are long furrows at the corners of the mouth on both the upper and lower jaws. The tooth rows number 24–25 in both jaws. The upper teeth are finely serrated and strongly oblique; the lower teeth have a similar shape, though the serrations are smaller and the tips curve gently upward.[2][8] The teeth of juveniles are smooth-edged.[14]

The broad, triangular pectoral fins originate below the third or fourth gill slits, and are no longer than the front margin of the first dorsal fin. The anal fin is about twice as long as the second dorsal fin and preceded by long ridges. The first dorsal fin originates over the pectoral fin free rear tips, and the much smaller second dorsal fin originates over the last third of the anal fin base. The dorsal fins do not have a ridge between them. The lower lobe of the caudal fin is well-developed and the upper lobe has a ventral notch near the tip. This shark is plain gray, brown-gray, or purple-gray above, and white below. The leading edge of the first dorsal fin and the trailing edge of the caudal fin may be dark, and the trailing edges of the pectoral fins may be light.[2][8]

Biology and ecology

One of the most (if not the most) abundant near-shore sharks within its range, the milk shark feeds mainly on small benthic and schooling bony fishes. Occasionally squid, octopus, cuttlefish, crabs, shrimp, and gastropods are also taken.[2] In Shark Bay, the most important prey are silversides, herring, smelt-whitings, and wrasses; this is also the only local shark species that preys on the Waigeo seaperch (Psammoperca waigiensis), found in seagrass beds avoided by other sharks. In the Gulf of Carpentaria, it feeds mainly on halfbeaks, herring, and mullets, and is also a major predator of penaeid prawns. Smaller sharks eat proportionately more cephalopods and crustaceans, switching to fish as they grow older.[9][15]

Many predators feed on the milk shark, including larger sharks such as the blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus) and Australian blacktip shark (Carcharhinus tilstoni), and possibly also marine mammals.[14] Off KwaZulu-Natal, the decimation of large sharks by the use of gillnets to protect beaches has led to a recent increase in milk shark numbers.[16] A known parasite of this species is the copepod Pseudopandarus australis.[17] There is some evidence that male and female milk sharks segregate from each other.[13]

Life history

Like other requiem sharks, the milk shark is viviparous; females usually have a single functional ovary (on the left) and two functional uteruses divided into separate compartments for each embryo.[13] The details of its life history vary across different parts of its range. Females generally produce young every year, though some give birth every other year or even every third year.[13][18] Mating and parturition take place in spring or early summer (April to July) off western and southern Africa,[12][13][19] and in winter off India,[2] Alternately, off Oman parturition occurs year-round with a peak in spring.[11] Parturition also occurs continuously in Australian waters; in the Herald Bight of Shark Bay, the number of newborns peaks in April and again in July.[20][21] One proposed explanation for the lack of reproductive seasonality in these subpopulations is a lengthier and/or more complex reproductive cycle than has been detected (such as a period of dormancy in embryonic development, though there is presently no evidence of this occurring). Females do not store sperm internally.[11]

The litter size ranges from one to eight, with two to five being typical, increasing with female size.[2][19] In Omanese waters, females on average outnumber males in a litter by more than 2:1, and all-female litters are not uncommon.[11] Similar but less extreme sex imbalances have also been reported from litters of milk sharks off Senegal and eastern India.[13][22] The reason for this imbalance is unknown, and it has not been observed in related species such as the Atlantic sharpnose shark (R. terraenovae).[11] Gestation of the embryos takes around a year and proceeds in three phases. In the first phase, lasting two months to an embryonic length of 63–65 mm (2.5–2.6 in), the embryo relies on yolk for sustenance and gas exchange occurs across its surface integument and possibly also the yolk sac. During the second phase, which also lasts for two months to an embryonic length of 81–104 mm (3.2–4.1 in), the external gill filaments develop and the yolk sac begins to be resorbed, the embyo ingesting histotroph (a nutritious substance secreted by the mother) in the meantime. In the third phase, lasting six to eight months, the depleted yolk sac is converted into a placental connection through which the fetus receives nourishment until birth.[13]

Young sharks are typically born at a length of 32.5–50.0 cm (12.8–19.7 in) and weigh 127–350 g (0.280–0.772 lb).[13] There is an atypical record of a female, caught off Mumbai, carrying a fetus only 23.7 cm (9.3 in) long that was already nearly fully developed, long before gestation was complete.[23] Pregnant females make use of inshore nursery areas to give birth, taking advantage of the warmer waters and abundant food; known nursery areas include the Banc d'Arguin National Park off Mauritania, and Cleveland Bay and Herald Bight off Australia.[19][20][21] In Herald Bight, large groups of small milk sharks can be found in shallow tidal pools, as well as in seagrass beds where they are sheltered from predators by the dense, tall vegetation. The sharks move out of these coastal embayments when they mature.[21]

Males and female milk sharks mature at lengths of 84–95 cm (33–37 in) and 89–100 cm (35–39 in) respectively off West Africa,[13] 68–72 cm (27–28 in) and 70–80 cm (28–31 in) respectively off southern Africa,[24] and 63–71 cm (25–28 in) and 62–74 cm (24–29 in) respectively off Oman. These discrepancies in maturation size may be a result of regional variation or incidental selection from heavy fishing pressure.[11] The growth rate for milk sharks off Chennai have been calculated as 10 cm (3.9 in) in the first year, 9 cm (3.5 in) in the second year, 7 cm (2.8 in) in the third year, 6 cm (2.4 in) in the fourth year, 5 cm (2.0 in) in the fifth year, and 3–4 cm (1.2–1.6 in) per year from then on.[22] The age at maturation is thought to be 2–3 years, and the maximum lifespan is at least 8 years.[1]

Human interactions

The milk shark is harmless to humans because of its small size and teeth.[14] Caught using longlines, gillnets, trawls, and hook-and-line, this shark is marketed fresh or dried and salted for human consumption, and is also used for shark fin soup and fishmeal.[1][14] Its abundance makes it a significant component of artisanal and commercial fisheries across its range. Off northern Australia, it ranks among the most common sharks caught in trawls, and comprises 2% and 6% of the annual gillnet and longline catches, respectively.[1] This species is also one of the most commercially important sharks caught off Senegal, Mauritania, Oman, and India.[25] Some sport fishers regard it as a game fish.[14]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature has listed the milk shark under Least Concern; despite being heavily fished, it has a wide distribution and remains fairly common. The reproductive characteristics of this species suggests it is capable of withstanding a somewhat high level of exploitation, though not as much as the grey sharpnose shark (R. oligolinx) or Australian sharpnose shark (R. taylori).[1] In the 1980s and early 1990s, stock assessments of the milk shark off India's Verval coast concluded catches by gillnet and trawl fisheries were below the maximum sustainable level. However, these studies were based on methodologies that have subsequently been proven unreliable for shark populations. Moreover, fishing pressure in the region has increased substantially since the assessments were conducted.[14][25]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Simpfendorfer, C.A. (2003). Rhizoprionodon acutus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved September 10, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization. pp. 525–526. ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Van der Elst, R. (1993). A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa (third ed.). Struik. p. 46. ISBN 1-86825-394-5.

- 1 2 Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2009). "Rhizoprionodon acutus" in FishBase. September 2009 version.

- ↑ Naylor, G.J.P. (1992). "The phylogenetic relationships among requiem and hammerhead sharks: inferring phylogeny when thousands of equally most parsimonious trees result". Cladistics 8 (4): 295–318. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1992.tb00073.x.

- 1 2 Carrier, J.C., J.A. Musick and M.R. Heithaus (2004). Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives. CRC Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-8493-1514-X.

- ↑ Compagno, L.J.V., M. Dando and S. Fowler (2005). Sharks of the World. Princeton University Press. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-0-691-12072-0.

- 1 2 3 Randall, J.E. and J.P. Hoover (1995). Coastal Fishes of Oman. University of Hawaii Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-8248-1808-3.

- 1 2 White, W.T., M.E. Platell and I.C. Potter (March 2004). "Comparisons between the diets of four abundant species of elasmobranchs in a subtropical embayment: implications for resource partitioning". Marine Biology 144 (3): 439–448. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1218-1.

- ↑ Rainboth, W.J. (1996). Fishes of the Cambodian Mekong. Food and Agriculture Organization. p. 51. ISBN 92-5-103743-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Henderson, A.C., J.L. McIlwain, H.S. Al-Oufi and A. Ambu-Ali (June 2006). "Reproductive biology of the milk shark Rhizoprionodon acutus and the bigeye houndshark Iago omanensis in the coastal waters of Oman". Journal of Fish Biology 68 (6): 1662–1678. doi:10.1111/j.0022-1112.2006.01011.x.

- 1 2 Cadenat, J. and J. Blache (1981). "Requins de Méditerranée et d'Atlantique (plus particulièrement de la côte occidentale d'Afrique)". ORSTOM 21: 1–330.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Capape, C., Y. Diatta, M. Diop, O. Guelorget, Y. Vergne and J. Quignard (2006). "Reproduction in the milk shark, Rhizoprionodon acutus (Ruppell, 1837) (Chondrichthyes: Carcharhinidae), from the coast of Senegal (eastern tropical Atlantic)". Acta Adriatica 47 (2): 111–126.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bester, C. Biological Profiles: Milk Shark. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on September 10, 2009.

- ↑ Salini, J.P., S.J.M. Blaber and D.T. Brewer (1990). "Diets of piscivorous fishes in a tropical Australian estuary, with special reference to predation on penaeid prawns". Marine Biology 105 (3): 363–374. doi:10.1007/BF01316307.

- ↑ Heemstra, E. and P. Heemstra (2004). Coastal Fishes of Southern Africa. NISC and SAIAB. p. 62. ISBN 1-920033-01-7.

- ↑ Cressey, R. and C. Simpfendorfer (1988). "Pseudopandarus australis, a new species of pandarid copepod from Australian sharks". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 101 (2): 340–345.

- ↑ Devadoss, P. (1988). "Observations on the breeding and development of some sharks". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India 30: 121–131.

- 1 2 3 Valadou, B., J. Brethes and C.A.O. Inejih (December 31, 2006). "Biological and ecological data of five elasmobranch species from the waters of the Banc d'Arguin National Park (Mauritania)". Cybium 30 (4): 313–322.

- 1 2 Simpfendorfer, C.A. and N.E. Milward (August 1993). "Utilisation of a tropical bay as a nursery area by sharks of the families Carcharhinidae and Sphyrnidae". Environmental Biology of Fishes 37 (4): 337–345. doi:10.1007/BF00005200.

- 1 2 3 White, W.T. and I.C. Potter (October 2004). "Habitat partitioning among four elasmobranch species in nearshore, shallow waters of a subtropical embayment in Western Australia". Marine Biology 145 (5): 1023–1032. doi:10.1007/s00227-004-1386-7.

- 1 2 Krishnamoorthi, B. and I. Jagadis (1986). "Biology and population dynamics of the grey dogshark, Rhizoprionodon (Rhizoprionodon) acutus (Ruppell), in Madras waters". Indian Journal of Fisheries 33 (4): 371–385.

- ↑ Setna, S.B. and P.N.Sarandghar (1949). "Breeding habits on Bombay elasmobranchs". Records of the Indian Museum 47: 107–124.

- ↑ Bass, A.J., J.D. D’Aubrey and N. Kistnasamy (1975). "Sharks of the east coast of southern Africa. III. The families Carcharhinidae (excluding Mustelus and Carcharhinus) and Sphyrnidae". Investigative Report of the Oceanographic Research Institute of South Africa 33: 1–100.

- 1 2 Fowler, S.L., R.D. Cavanagh, M. Camhi, G.H. Burgess, G.M. Cailliet, S.V. Fordham, C.A. Simpfendorfer, and J.A. Musick (2005). Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. p. 92–93, 146–147. ISBN 2-8317-0700-5.