Resistance thermometer

Resistance thermometers, also called resistance temperature detectors (RTDs), are sensors used to measure temperature by correlating the resistance of the RTD element with temperature. Most RTD elements consist of a length of fine coiled wire wrapped around a ceramic or glass core. The element is usually quite fragile, so it is often placed inside a sheathed probe to protect it. The RTD element is made from a pure material, typically platinum, nickel or copper. The material has a predictable change in resistance as the temperature changes and it is this predictable change that is used to determine temperature.

They are slowly replacing the use of thermocouples in many industrial applications below 600 °C, due to higher accuracy and repeatability.[1]

R vs T relationship of various metals

Common RTD sensing elements constructed of platinum, copper or nickel have a repeatable resistance versus temperature relationship (R vs T) and operating temperature range. The R vs T relationship is defined as the amount of resistance change of the sensor per degree of temperature change.[2] The relative change in resistance (temperature coefficient of resistance) varies only slightly over the useful range of the sensor.

Platinum was proposed by Sir William Siemens as an element for resistance temperature detector at the Bakerian lecture in 1871:[3] it is a noble metal and has the most stable resistance-temperature relationship over the largest temperature range. Nickel elements have a limited temperature range because the amount of change in resistance per degree of change in temperature becomes very non-linear at temperatures over 572 °F (300 °C). Copper has a very linear resistance-temperature relationship, however copper oxidizes at moderate temperatures and cannot be used over 302 °F (150 °C).

Platinum is the best metal for RTDs because it follows a very linear resistance-temperature relationship and it follows the R vs T relationship in a highly repeatable manner over a wide temperature range. The unique properties of platinum make it the material of choice for temperature standards over the range of -272.5 °C to 961.78 °C, and is used in the sensors that define the International Temperature Standard, ITS-90. Platinum is chosen also because of its chemical inertness.

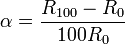

The significant characteristic of metals used as resistive elements is the linear approximation of the resistance versus temperature relationship between 0 and 100 °C. This temperature coefficient of resistance is called alpha, α. The equation below defines α; its units are ohm/ohm/°C.

the resistance of the sensor at 0 °C

the resistance of the sensor at 0 °C the resistance of the sensor at 100 °C

the resistance of the sensor at 100 °C

Pure platinum has an alpha of 0.003925 ohm/ohm/°C in the 0 to 100 °C range and is used in the construction of laboratory grade RTDs. Conversely two widely recognized standards for industrial RTDs IEC 60751 and ASTM E-1137 specify an alpha of 0.00385 ohms/ohm/°C. Before these standards were widely adopted several different alpha values were used. It is still possible to find older probes that are made with platinum that have alpha values of 0.003916 ohms/ohm/°C and 0.003902 ohms/ohm/°C.

These different alpha values for platinum are achieved by doping; basically carefully introducing impurities into the platinum. The impurities introduced during doping become embedded in the lattice structure of the platinum and result in a different R vs. T curve and hence alpha value.

Calibration

To characterize the R vs T relationship of any RTD over a temperature range that represents the planned range of use, calibration must be performed at temperatures other than 0 °C and 100 °C. This is necessary to meet calibration requirements, although RTD's are considered to be linear in operation it must be proven that they are accurate with regard to the temperatures they will actually be used (see details in Comparison calibration option). Two common calibration methods are the fixed point method and the comparison method.

- Fixed point calibration, used for the highest accuracy calibrations, uses the triple point, freezing point or melting point of pure substances such as water, zinc, tin, and argon to generate a known and repeatable temperature. These cells allow the user to reproduce actual conditions of the ITS-90 temperature scale. Fixed point calibrations provide extremely accurate calibrations (within ±0.001 °C). A common fixed point calibration method for industrial-grade probes is the ice bath. The equipment is inexpensive, easy to use, and can accommodate several sensors at once. The ice point is designated as a secondary standard because its accuracy is ±0.005 °C (±0.009 °F), compared to ±0.001 °C (±0.0018 °F) for primary fixed points.

- Comparison calibrations, commonly used with secondary SPRTs and industrial RTDs, the thermometers being calibrated are compared to calibrated thermometers by means of a bath whose temperature is uniformly stable. Unlike fixed point calibrations, comparisons can be made at any temperature between –100 °C and 500 °C (–148 °F to 932 °F). This method might be more cost-effective since several sensors can be calibrated simultaneously with automated equipment. These electrically heated and well-stirred baths use silicone oils and molten salts as the medium for the various calibration temperatures.

Element types

There are five main categories of RTD sensors: thin film, wire-wound, and coiled elements. While these types are the ones most widely used in industry there are some places where other more exotic shapes are used, for example carbon resistors are used at ultra low temperatures (-173 °C to -273 °C).[4]

- Carbon resistor elements are widely available and are very inexpensive. They have very reproducible results at low temperatures. They are the most reliable form at extremely low temperatures. They generally do not suffer from significant hysteresis or strain gauge effects.

- Strain free elements use a wire coil minimally supported within a sealed housing filled with an inert gas. These sensors are used up to 961.78 °C and are used in the SPRT’s that define ITS-90. They consist of platinum wire loosely coiled over a support structure so the element is free to expand and contract with temperature. They are very susceptible to shock and vibration as the loops of platinum can sway back and forth causing deformation.

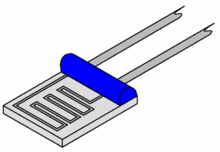

- Thin film elements have a sensing element that is formed by depositing a very thin layer of resistive material, normally platinum, on a ceramic substrate. This layer is usually just 10 to 100 angstroms (1 to 10 nanometers) thick.[5] This film is then coated with an epoxy or glass that helps protect the deposited film and also acts as a strain relief for the external lead-wires. Disadvantages of this type are that they are not as stable as their wire wound or coiled counterparts. They also can only be used over a limited temperature range due to the different expansion rates of the substrate and resistive deposited giving a "strain gauge" effect that can be seen in the resistive temperature coefficient. These elements work with temperatures to 300 °C without further packaging but can operate up to 600°C when suitably encapsulated in glass or ceramic. Nowadays there are special high temperature RTD elements which can be used up to 900°C with the right encapsulation.

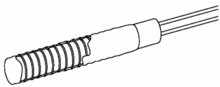

- Wire-wound elements can have greater accuracy, especially for wide temperature ranges. The coil diameter provides a compromise between mechanical stability and allowing expansion of the wire to minimize strain and consequential drift. The sensing wire is wrapped around an insulating mandrel or core. The winding core can be round or flat, but must be an electrical insulator. The coefficient of thermal expansion of the winding core material is matched to the sensing wire to minimize any mechanical strain. This strain on the element wire will result in a thermal measurement error. The sensing wire is connected to a larger wire, usually referred to as the element lead or wire. This wire is selected to be compatible with the sensing wire so that the combination does not generate an emf that would distort the thermal measurement. These elements work with temperatures to 660 °C.

- Coiled elements have largely replaced wire-wound elements in industry. This design has a wire coil which can expand freely over temperature, held in place by some mechanical support which lets the coil keep its shape. This “strain free” design allows the sensing wire to expand and contract free of influence from other materials; in this respect it is similar to the SPRT, the primary standard upon which ITS-90 is based, while providing the durability necessary for industrial use. The basis of the sensing element is a small coil of platinum sensing wire. This coil resembles a filament in an incandescent light bulb. The housing or mandrel is a hard fired ceramic oxide tube with equally spaced bores that run transverse to the axes. The coil is inserted in the bores of the mandrel and then packed with a very finely ground ceramic powder. This permits the sensing wire to move while still remaining in good thermal contact with the process. These elements work with temperatures to 850 °C.

The current international standard which specifies tolerance, and the temperature-to-electrical resistance relationship for platinum resistance thermometers (PRTs) is IEC 60751:2008; ASTM E1137 is also used in the United States. By far the most common devices used in industry have a nominal resistance of 100 ohms at 0 °C, and are called Pt100 sensors ('Pt' is the symbol for platinum, 100 for the resistance in ohm at 0 °C). It is also possible to get Pt1000 sensors where 1000 is for the resistance in ohm at 0 °C. The sensitivity of a standard 100 ohm sensor is a nominal 0.385 ohm/°C. RTDs with a sensitivity of 0.375 and 0.392 ohm/°C as well as a variety of others are also available.

Function

Resistance thermometers are constructed in a number of forms and offer greater stability, accuracy and repeatability in some cases than thermocouples. While thermocouples use the Seebeck effect to generate a voltage, resistance thermometers use electrical resistance and require a power source to operate. The resistance ideally varies nearly linearly with temperature per the Callendar Van-Dusen equation.

The platinum detecting wire needs to be kept free of contamination to remain stable. A platinum wire or film is supported on a former in such a way that it gets minimal differential expansion or other strains from its former, yet is reasonably resistant to vibration. RTD assemblies made from iron or copper are also used in some applications. Commercial platinum grades are produced which exhibit a temperature coefficient of resistance 0.00385/°C (0.385%/°C) (European Fundamental Interval).[6] The sensor is usually made to have a resistance of 100 Ω at 0 °C. This is defined in BS EN 60751:1996 (taken from IEC 60751:1995). The American Fundamental Interval is 0.00392/°C,[7] based on using a purer grade of platinum than the European standard. The American standard is from the Scientific Apparatus Manufacturers Association (SAMA), who are no longer in this standards field. As a result the "American standard" is hardly the standard even in the US.

Lead wire resistance can also be a factor; adopting three- and four-wire, instead of two-wire, connections can eliminate connection lead resistance effects from measurements (see below); three-wire connection is sufficient for most purposes and almost universal industrial practice. Four-wire connections are used for the most precise applications.

Advantages and limitations

The advantages of platinum resistance thermometers include:

- High accuracy

- Low drift

- Wide operating range

- Suitability for precision applications.

Limitations: RTDs in industrial applications are rarely used above 660 °C. At temperatures above 660 °C it becomes increasingly difficult to prevent the platinum from becoming contaminated by impurities from the metal sheath of the thermometer. This is why laboratory standard thermometers replace the metal sheath with a glass construction. At very low temperatures, say below -270 °C (or 3 K), because there are very few phonons, the resistance of an RTD is mainly determined by impurities and boundary scattering and thus basically independent of temperature. As a result, the sensitivity of the RTD is essentially zero and therefore not useful.

Compared to thermistors, platinum RTDs are less sensitive to small temperature changes and have a slower response time. However, thermistors have a smaller temperature range and stability.

RTDs vs thermocouples

The two most common ways of measuring industrial temperatures are with resistance temperature detectors (RTDs) and thermocouples. Choice between them is usually determined by four factors.

- temperature: If process temperatures are between −200 to 500 °C (−328.0 to 932.0 °F), an industrial RTD is the preferred option. Thermocouples have a range of −180 to 2,320 °C (−292.0 to 4,208.0 °F),[8] so for temperatures above 500 °C (932 °F) they are the only contact temperature measurement device.

- response time: If the process requires a very fast response to temperature changes—fractions of a second as opposed to seconds (e.g. 2.5 to 10 s)—then a thermocouple is the best choice. Time response is measured by immersing the sensor in water moving at 1 m/s (3 ft/s) with a 63.2% step change.

- size : A standard RTD sheath is 3.175 to 6.35 mm (0.1250 to 0.2500 in) in diameter; sheath diameters for thermocouples can be less than 1.6 mm (0.063 in).

- accuracy and stability requirements: If a tolerance of 2 °C is acceptable and the highest level of repeatability is not required, a thermocouple will serve. RTDs are capable of higher accuracy and can maintain stability for many years, while thermocouples can drift within the first few hours of use.

Construction

These elements nearly always require insulated leads attached. At temperatures below about 250 °C PVC, silicone rubber or PTFE insulators are used. Above this, glass fibre or ceramic are used. The measuring point, and usually most of the leads, require a housing or protective sleeve, often made of a metal alloy which is chemically inert to the process being monitored. Selecting and designing protection sheaths can require more care than the actual sensor, as the sheath must withstand chemical or physical attack and provide convenient attachment points.

Wiring configurations

Two-wire configuration

The simplest resistance thermometer configuration uses two wires. It is only used when high accuracy is not required, as the resistance of the connecting wires is added to that of the sensor, leading to errors of measurement. This configuration allows use of 100 meters of cable. This applies equally to balanced bridge and fixed bridge system.

For a balanced bridge the usual setting is with R2=R3 and R1 around the middle of the range of the RTD. So for example, if we are going to measure between 0ºC and 100ºC, RTD resistance will range from 100 ohm to 138,5 ohm. We would choose R1=120 ohm. In that way we get a small measured voltage in the bridge.

Three-wire configuration

In order to minimize the effects of the lead resistances, a three-wire configuration can be used. Using this method the two leads to the sensor are on adjoining arms. There is a lead resistance in each arm of the bridge so that the resistance is cancelled out, so long as the two lead resistances are accurately the same. This configuration allows up to 600 meters of cable.

As in the case with the 2-wire connection the usual setting is with R2=R3 and R1 around the middle of the range of the RTD.

Four-wire configuration

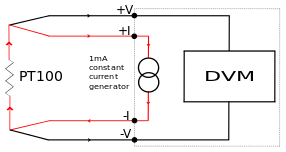

The four-wire resistance configuration increases the accuracy of measurement of resistance. Four-terminal sensing eliminates voltage drop in the measuring leads as a contribution to error. To increase accuracy further, any residual thermoelectric voltages generated by different wire types or screwed connections are eliminated by reversal of the direction of the 1 mA current and the leads to the DVM (Digital Voltmeter). The thermoelectric voltages will be produced in one direction only. By averaging the reversed measurements, the thermoelectric error voltages are cancelled out.

Classifications of RTDs

The highest accuracy of all PRTs is the Standard platinum Resistance Thermometers (SPRTs). This accuracy is achieved at the expense of durability and cost. The SPRTs elements are wound from reference grade platinum wire. Internal lead wires are usually made from platinum while internal supports are made from quartz or fused silica. The sheaths are usually made from quartz or sometimes Inconel depending on temperature range. Larger diameter platinum wire is used, which drives up the cost and results in a lower resistance for the probe (typically 25.5 ohms). SPRTs have a wide temperature range (-200 °C to 1000 °C) and are approximately accurate to ±0.001 °C over the temperature range. SPRTs are only appropriate for laboratory use.

Another classification of laboratory PRTs is Secondary Standard platinum Resistance Thermometers (Secondary SPRTs). They are constructed like the SPRT, but the materials are more cost-effective. SPRTs commonly use reference grade, high purity smaller diameter platinum wire, metal sheaths and ceramic type insulators. Internal lead wires are usually a nickel-based alloy. Secondary SPRTs are limited in temperature range (-200 °C to 500 °C) and are approximately accurate to ±0.03 °C over the temperature range.

Industrial PRTs are designed to withstand industrial environments. They can be almost as durable as a thermocouple. Depending on the application industrial PRTs can use thin film elements or coil wound elements. The internal lead wires can range from PTFE insulated stranded nickel plated copper to silver wire, depending on the sensor size and application. Sheath material is typically stainless steel; higher temperature applications may demand Inconel. Other materials are used for specialized applications.

History

The application of the tendency of electrical conductors to increase their electrical resistance with rising temperature was first described by Sir William Siemens at the Bakerian Lecture of 1871 before the Royal Society of Great Britain. The necessary methods of construction were established by Callendar, Griffiths, Holborn and Wein between 1885 and 1900.

Standard resistance thermometer data

Temperature sensors are usually supplied with thin-film elements. The resistance elements are rated in accordance with BS EN 60751:2008 as:

| Tolerance Class | Valid Range |

|---|---|

| F 0.3 | -50 to +500 °C |

| F 0.15 | -30 to +300 °C |

| F 0.1 | 0 to +150 °C |

Resistance thermometer elements can be supplied which function up to 1000 °C. The relation between temperature and resistance is given by the Callendar-Van Dusen equation,

Here,

is the resistance at temperature T,

is the resistance at temperature T,

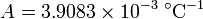

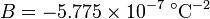

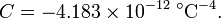

is the resistance at 0 °C, and the constants (for an alpha=0.00385 platinum RTD) are

is the resistance at 0 °C, and the constants (for an alpha=0.00385 platinum RTD) are

Since the B and C coefficients are relatively small, the resistance changes almost linearly with the temperature.

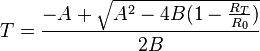

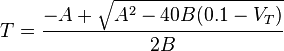

For positive temperature, if we resolve the quadratic equation we obtain the following relationship between temperature and resistance:

If we now consider a four-wire configuration with a 1mA precision current source,[9] we obtain the following relationship between temperature and measured voltage

Values for various popular resistance thermometers

| Temperature in °C |

ITS-90 Pt100[10] in Ω |

Pt100 in Ω |

Pt1000 in Ω |

PTC in Ω |

NTC in Ω |

NTC in Ω |

NTC in Ω |

NTC in Ω |

NTC in Ω |

| Typ: 404 | Typ: 501 | Typ: 201 | Typ: 101 | Typ: 102 | Typ: 103 | Typ: 104 | Typ: 105 | ||

| −50 | 79.901192 | 80.31 | 803.1 | 1032 | |||||

| −45 | 81.925089 | 82.29 | 822.9 | 1084 | |||||

| −40 | 83.945642 | 84.27 | 842.7 | 1135 | 50475 | ||||

| −35 | 85.962913 | 86.25 | 862.5 | 1191 | 36405 | ||||

| −30 | 87.976963 | 88.22 | 882.2 | 1246 | 26550 | ||||

| −25 | 89.987844 | 90.19 | 901.9 | 1306 | 26083 | 19560 | |||

| −20 | 91.995602 | 92.16 | 921.6 | 1366 | 19414 | 14560 | |||

| −15 | 94.000276 | 94.12 | 941.2 | 1430 | 14596 | 10943 | |||

| −10 | 96.001893 | 96.09 | 960.9 | 1493 | 11066 | 8299 | |||

| −5 | 98.000470 | 98.04 | 980.4 | 1561 | 31389 | 8466 | |||

| 0 | 99.996012 | 100.00 | 1000.0 | 1628 | 23868 | 6536 | |||

| 5 | 101.988430 | 101.95 | 1019.5 | 1700 | 18299 | 5078 | |||

| 10 | 103.977803 | 103.90 | 1039.0 | 1771 | 14130 | 3986 | |||

| 15 | 105.964137 | 105.85 | 1058.5 | 1847 | 10998 | ||||

| 20 | 107.947437 | 107.79 | 1077.9 | 1922 | 8618 | ||||

| 25 | 109.927708 | 109.73 | 1097.3 | 2000 | 6800 | 15000 | |||

| 30 | 111.904954 | 111.67 | 1116.7 | 2080 | 5401 | 11933 | |||

| 35 | 113.879179 | 113.61 | 1136.1 | 2162 | 4317 | 9522 | |||

| 40 | 115.850387 | 115.54 | 1155.4 | 2244 | 3471 | 7657 | |||

| 45 | 117.818581 | 117.47 | 1174.7 | 2330 | 6194 | ||||

| 50 | 119.783766 | 119.40 | 1194.0 | 2415 | 5039 | ||||

| 55 | 121.745943 | 121.32 | 1213.2 | 2505 | 4299 | 27475 | |||

| 60 | 123.705116 | 123.24 | 1232.4 | 2595 | 3756 | 22590 | |||

| 65 | 125.661289 | 125.16 | 1251.6 | 2689 | 18668 | ||||

| 70 | 127.614463 | 127.07 | 1270.7 | 2782 | 15052 | ||||

| 75 | 129.564642 | 128.98 | 1289.8 | 2880 | 12932 | ||||

| 80 | 131.511828 | 130.89 | 1308.9 | 2977 | 10837 | ||||

| 85 | 133.456024 | 132.80 | 1328.0 | 3079 | 9121 | ||||

| 90 | 135.397232 | 134.70 | 1347.0 | 3180 | 7708 | ||||

| 95 | 137.335456 | 136.60 | 1366.0 | 3285 | 6539 | ||||

| 100 | 139.270697 | 138.50 | 1385.0 | 3390 | |||||

| 105 | 141.202958 | 140.39 | 1403.9 | ||||||

| 110 | 143.132242 | 142.29 | 1422.9 | ||||||

| 150 | 158.459633 | 157.31 | 1573.1 | ||||||

| 200 | 177.353177 | 175.84 | 1758.4 |

See also

References

- ↑ Sensor Technology Series: Biomedical Sensors, retrieved 2009-09-18

- ↑ Sensor Technology Series: Biomedical Sensors, retrieved 2009-09-18

- ↑ Siemens, William (1871). "On the Increase of Electrical Resistance in Conductors with Rise of Temperature, and Its Application to the Measure of Ordinary and Furnace Temperatures; Also on a Simple Method of Measuring Electrical Resistances". The Bakerian Lecture (Royal Society). Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ↑ Carbon Resistors (PDF), retrieved 2011-11-16

- ↑ RTD Element Types (PDF), retrieved 2011-11-16

- ↑ http://www.instrumentationservices.net/hand-held-thermometers.php

- ↑ http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/electric/restmp.html

- ↑ http://www.omega.com/temperature/Z/pdf/z241-245.pdf

- ↑ Precision Low Current Source, retrieved 2015-05-20

- ↑ Strouse, G.F. (2008). Standard Platinum Resistance Thermometer Calibrations from the Ar TP to the Ag FP. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology.

![R_T = R_0 \left[ 1 + AT + BT^2 + CT^3 (T-100) \right] \; (-200\;{}^{\circ}\mathrm{C} < T < 0\;{}^{\circ}\mathrm{C}),](../I/m/fb3b98a47690c02e31344ca7c6ac8c25.png)

![R_T = R_0 \left[ 1 + AT + BT^2 \right] \; (0\;{}^{\circ}\mathrm{C} \leq T < 850\;{}^{\circ}\mathrm{C}).](../I/m/9a8ee16cacd873b4592af95df3dddfc1.png)