Residuated lattice

In abstract algebra, a residuated lattice is an algebraic structure that is simultaneously a lattice x ≤ y and a monoid x•y which admits operations x\z and z/y loosely analogous to division or implication when x•y is viewed as multiplication or conjunction respectively. Called respectively right and left residuals, these operations coincide when the monoid is commutative. The general concept was introduced by Ward and Dilworth in 1939. Examples, some of which existed prior to the general concept, include Boolean algebras, Heyting algebras, residuated Boolean algebras, relation algebras, and MV-algebras. Residuated semilattices omit the meet operation ∧, for example Kleene algebras and action algebras.

Definition

In mathematics, a residuated lattice is an algebraic structure L = (L, ≤, •, I) such that

- (i) (L, ≤) is a lattice.

- (ii) (L, •, I) is a monoid.

- (iii) For all z there exists for every x a greatest y, and for every y a greatest x, such that x•y ≤ z (the residuation properties).

In (iii), the "greatest y", being a function of z and x, is denoted x\z and called the right residual of z by x, thinking of it as what remains of z on the right after "dividing" z on the left by x. Dually the "greatest x" is denoted z/y and called the left residual of z by y. An equivalent more formal statement of (iii) that uses these operations to name these greatest values is

(iii)' for all x, y, z in L, y ≤ x\z ⇔ x•y ≤ z ⇔ x ≤ z/y.

As suggested by the notation the residuals are a form of quotient. More precisely, for a given x in L, the unary operations x• and x\ are respectively the lower and upper adjoints of a Galois connection on L, and dually for the two functions •y and /y. By the same reasoning that applies to any Galois connection, we have yet another definition of the residuals, namely,

- x•(x\y) ≤ y ≤ x\(x•y), and

- (y/x)•x ≤ y ≤ (y•x)/x,

together with the requirement that x•y be monotone in x and y. (When axiomatized using (iii) or (iii)' monotonicity becomes a theorem and hence not required in the axiomatization.) These give a sense in which the functions x• and x\ are pseudoinverses or adjoints of each other, and likewise for •x and /x.

This last definition is purely in terms of inequalities, noting that monotonicity can be axiomatized as x•y ≤ (x∨z)•y and similarly for the other operations and their arguments. Moreover any inequality x ≤ y can be expressed equivalently as an equation, either x∧y = x or x∨y = y. This along with the equations axiomatizing lattices and monoids then yields a purely equational definition of residuated lattices, provided the requisite operations are adjoined to the signature (L, ≤, •, I) thereby expanding it to (L, ∧, ∨, •, I, /, \). When thus organized, residuated lattices form an equational class or variety, whose homomorphisms respect the residuals as well as the lattice and monoid operations. Note that distributivity x•(y∨z) = (x•y) ∨ (x•z) and x•0 = 0 are consequences of these axioms and so do not need to be made part of the definition. This necessary distributivity of • over ∨ does not in general entail distributivity of ∧ over ∨, that is, a residuated lattice need not be a distributive lattice. However it does do so when • and ∧ are the same operation, a special case of residuated lattices called a Heyting algebra.

Alternative notations for x•y include x◦y, x;y (relation algebra), and x⊗y (linear logic). Alternatives for I include e and 1'. Alternative notations for the residuals are x → y for x\y and y ← x for y/x, suggested by the similarity between residuation and implication in logic, with the multiplication of the monoid understood as a form of conjunction that need not be commutative. When the monoid is commutative the two residuals coincide. When not commutative, the intuitive meaning of the monoid as conjunction and the residuals as implications can be understood as having a temporal quality: x•y means x and then y, x → y means had x (in the past) then y (now), and y ← x means if-ever x (in the future) then y (at that time), as illustrated by the natural language example at the end of the examples.

Examples

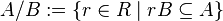

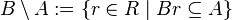

One of the original motivations for the study of residuated lattices was the lattice of ideals of a ring. Given a ring R, the ideals of R, denoted Id(R), forms a complete lattice with set intersection acting as the meet operation and "ideal addition" acting as the join operation. The monoid operation • is given by "ideal multiplication", and the element R of Id(R) acts as the identity for this operation. Given two ideals A and B in Id(R), the residuals are given by

It is worth noting that {0}/B and B\{0} are respectively the left and right annihilators of B. This residuation is related to the conductor (or transporter) in commutative algebra written as (A:B)=A/B. One difference in usage is that B need not be an ideal of R: it may just be a subset.

Boolean algebras and Heyting algebras are commutative residuated lattices in which x•y = x∧y (whence the unit I is the top element 1 of the algebra) and both residuals x\y and y/x are the same operation, namely implication x → y. The second example is quite general since Heyting algebras include all finite distributive lattices, as well as all chains or total orders forming a complete lattice, for example the unit interval [0,1] in the real line, or the integers and ± .

.

The structure (Z, min, max, +, 0, −, −) (the integers with subtraction for both residuals) is a commutative residuated lattice such that the unit of the monoid is not the greatest element (indeed there is no least or greatest integer), and the multiplication of the monoid is not the meet operation of the lattice. In this example the inequalities are equalities because − (subtraction) is not merely the adjoint or pseudoinverse of + but the true inverse. Any totally ordered group under addition such as the rationals or the reals can be substituted for the integers in this example. The nonnegative portion of any of these examples is an example provided min and max are interchanged and − is replaced by monus, defined (in this case) so that x-y = 0 when x ≤ y and otherwise is ordinary subtraction.

A more general class of examples is given by the Boolean algebra of all binary relations on a set X, namely the power set of X2, made a residuated lattice by taking the monoid multiplication • to be composition of relations and the monoid unit to be the identity relation I on X consisting of all pairs (x,x) for x in X. Given two relations R and S on X, the right residual R\S of S by R is the binary relation such that x(R\S)y holds just when for all z in X, zRx implies zSy (notice the connection with implication). The left residual is the mirror image of this: y(S/R)x holds just when for all z in X, xRz implies ySz.

This can be illustrated with the binary relations < and > on {0,1} in which 0 < 1 and 1 > 0 are the only relationships that hold. Then x(>\<)y holds just when x = 1, while x(</>)y holds just when y = 0, showing that residuation of < by > is different depending on whether we residuate on the right or the left. This difference is a consequence of the difference between <•> and >•<, where the only relationships that hold are 0(<•>)0 (since 0<1>0) and 1(>•<)1 (since 1>0<1). Had we chosen ≤ and ≥ instead of < and >, ≥\≤ and ≤/≥ would have been the same because ≤•≥ = ≥•≤, both of which always hold between all x and y (since x≤1≥y and x≥0≤y).

The Boolean algebra 2Σ* of all formal languages over an alphabet (set) Σ forms a residuated lattice whose monoid multiplication is language concatenation LM and whose monoid unit I is the language {ε} consisting of just the empty string ε. The right residual M\L consists of all words w over Σ such that Mw ⊆ L. The left residual L/M is the same with wM in place of Mw.

The residuated lattice of all binary relations on X is finite just when X is finite, and commutative just when X has at most one element. When X is empty the algebra is the degenerate Boolean algebra in which 0 = 1 = I. The residuated lattice of all languages on Σ is commutative just when Σ has at most one letter. It is finite just when Σ is empty, consisting of the two languages 0 (the empty language {}) and the monoid unit I = {ε} = 1.

The examples forming a Boolean algebra have special properties treated in the article on residuated Boolean algebras.

In natural language residuated lattices formalize the logic of "and" when used with its noncommutative meaning of "and then." Setting x = bet, y = win, z = rich, we can read x•y ≤ z as "bet and then win entails rich." By the axioms this is equivalent to y ≤ x→z meaning "win entails had bet then rich", and also to x ≤ z←y meaning "bet entails if-ever win then rich." Humans readily detect such non-sequiturs as "bet entails had win then rich" and "win entails if-ever bet then rich" as both being equivalent to the wishful thinking "win and then bet entails rich." Humans do not so readily detect that Peirce's law ((P→Q)→P)→P is a tautology, giving an interesting situation where humans exhibit more proficiency with nonclassical reasoning than classical.

Residuated semilattice

A residuated semilattice is defined almost identically for residuated lattices, omitting just the meet operation ∧. Thus it is an algebraic structure L = (L, ∨, •, 1, /, \) satisfying all the residuated lattice equations as specified above except those containing an occurrence of the symbol ∧. The option of defining x ≤ y as x∧y = x is then not available, leaving only the other option x∨y = y (or any equivalent thereof).

Any residuated lattice can be made a residuated semilattice simply by omitting ∧. Residuated semilattices arise in connection with action algebras, which are residuated semilattices that are also Kleene algebras, for which ∧ is ordinarily not required.

See also

References

- Ward, Morgan, and Robert P. Dilworth (1939) "Residuated lattices," Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 45: 335-54. Reprinted in Bogart, K, Freese, R., and Kung, J., eds. (1990) The Dilworth Theorems: Selected Papers of R.P. Dilworth Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Nikolaos Galatos, Peter Jipsen, Tomasz Kowalski, and Hiroakira Ono (2007), Residuated Lattices. An Algebraic Glimpse at Substructural Logics, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-444-52141-5.