Republika Srpska

| Republika Srpska Република Српска |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Моја Република[1] Moja Republika My Republic |

||||||

_-_colored.svg.png) Location of the Republika Srpska (orange) and Brčko District (green) within Bosnia and Herzegovina.a

|

||||||

| Capital | Sarajevo (Istočno Sarajevo)[2] (de jure) Banja Luka (de facto) | |||||

| Largest city | Banja Luka | |||||

| Official languages | Serbian, Bosnian and Croatianb | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary system | |||||

| • | President | Milorad Dodik | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Željka Cvijanović | ||||

| Legislature | People's Assembly | |||||

| Formation | ||||||

| • | Proclaimed | 9 January 1992 | ||||

| • | Recognized as part of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

14 December 1995 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 24,857 km2 9,597 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | n/a | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2013 census | 1,326,991 d[3] | ||||

| • | Density | 53,3/km2 155/sq mi |

||||

| Currency | Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark (BAM) | |||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Calling code | +387 | |||||

| b. | The Constitution of Republika Srpska avoids naming the languages, instead listing them as "the language of the Serb people, the language of the Bosniak people and the language of the Croat people." (because there is no consensus whether this is the same language or three different languages) [4] | |||||

| c. | Including refugees abroad. | |||||

| d. | Excluding Republika Srpska's 48% of the Brčko District | |||||

The Republika Srpska (Serbian Cyrillic: Република Српскa, pronounced [repǔblika sr̩̂pskaː]) is an administrative entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is one of two administrative entities, the other being the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[5] The de jure capital of Republika Srpska is Sarajevo, the de facto capital is Banja Luka.

Name

In the Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian languages, Republika Srpska means "Serb Republic". The second word is a nominalized adjective derived by adding the suffix -ska to srb-, the root of the noun Srbin, meaning Serb. The -ps- sequence rather than -bs- is a result of voicing assimilation. Although the name Republika Srpska is sometimes glossed as Serb Republic[6] or Bosnian Serb Republic (Serbian: Republika Bosanskih Srba / Република Босанских Срба),[7] and the government of Republika Srpska uses the semi-Anglicized term Republic of Srpska in English translations of official documents, western news sources such as the BBC,[8] The New York Times,[9] and The Guardian[10] generally refer to the entity as the Republika Srpska.

In a July 2014 interview for Press, Dragoslav Bokan claimed that he, Goran Marić, and Sonja Karadžić (daughter of Radovan Karadžić) came up with the name Srpska as requested of them by Velibor Ostojić, then-Minister of Information of the entity.[11]

History

In a session on 14–15 October 1991, the Parliament of Bosnia approved the "Memorandum on Sovereignty", as had already been done by Slovenia and Croatia. The memorandum was adopted despite opposition from 83 Serb deputies, belonging to the Serb Democratic Party (most of the Serb parliamentary representatives) as well as the Serbian Renewal Movement and the Union of Reform Forces, who regarded the move as illegal.[12][13]

On 24 October 1991, the Serb deputies formed the Assembly of the Serb People in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Skupština srpskog naroda u Bosni i Hercegovini) to be the highest representative and legislative body of the Bosnian Serb population,[14][15] ending the tripartite coalition.

The Union of Reform Forces soon ceased to exist but its members remained in the assembly as the Independent Members of Parliament Caucus. The assembly undertook to address the achievement of equality between the Serbs and other peoples and the protection of the Serbs' interests, which they contended had been jeopardized by decisions of the Bosnian parliament.[14] On 9 January 1992, the assembly proclaimed the Republic of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Republika srpskog naroda Bosne i Hercegovine), declaring it part of Yugoslavia.[16]

On 28 February 1992 the assembly adopted the Constitution of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (the name adopted instead of the previous Republika srpskog naroda Bosne i Hercegovine), which would include districts, municipalities, and regions where Serbs were the majority and also those where they had allegedly become a minority because of persecution during World War II. The republic was part of Yugoslavia and could enter into union with political bodies representing other peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[17]

The Bosnian parliament, without its Serb deputies, held a referendum on the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 29 February and 1 March 1992, but most Serbs boycotted it since the assembly had previously (9–10 November 1991) held a plebiscite in the Serb regions, 96% having opted for membership of the Yugoslav federation formed by Serbia and Montenegro.[18]

The referendum had a 64% turnout and 92.7% or 99% (according to different sources) voted for independence.[19][20] On 6 March the Bosnian parliament promulgated the results of the referendum, proclaiming the republic's independence from Yugoslavia. The republic's independence was recognized by the European Community on 6 April 1992 and by the United States on 7 April. On the same day the Serbs' assembly in session in Banja Luka declared a severance of governmental ties with Bosnia and Herzegovina.[21] The name Republika Srpska was adopted on 12 August 1992.[22]

The political controversy escalated into the Bosnian War, which would last until the autumn of 1995. According to numerous verdicts of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia the former president of Republika Srpska, Radovan Karadžić, is currently under trial.[23] The top military general, Ratko Mladić, was arrested on 26 May 2011 in connection with the siege of Sarajevo and the Srebrenica massacre.[24]

The war was ended by the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, reached at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio, on 21 November and formally signed in Paris on 14 December 1995. Annex 4 of the Agreement is the current Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, recognising Republka Srpska as one of its two main political-territorial divisions and defining the governmental functions and powers of the two entities. The boundary lines between the entities were delineated in Annex 2 of the Agreement.[25]

Between 1992 and 2008, the Constitution of Republika Srpska was amended 121 times. Article 1 states that Republika Srpska is a territorially unified, indivisible and inalienable constitutional and legal entity that shall independently perform its constitutional, legislative, executive, and judicial functions.[26]

Impact of war

The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina resulted in major changes in the country, some of which were quantified in a 1998 UNESCO report. Outside the Serb region, 50% of homes were damaged and 6% destroyed, while in the Serb region, 25% of homes were damaged and 5% destroyed. Some two million people, about half the country's population, were displaced. In 1996 there were some 435,346 ethnic Serb refugees from the Federation in Republika Srpska, while another 197,925 had gone to Serbia. In 1991, 27% of the non-agricultural labor force was unemployed in Bosnia and this number increased due to the war.[27] By 2009, the unemployment rate in Bosnia and Herzegovina was estimated at 29%, according to the CIA's The World Factbook.[28]

Republika Srpska's population of Serbs had increased by 547,741 due to the influx of ethnic Serb refugees from the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the former unrecognised state of the Republic of Serbian Krajina in the new Republic of Croatia.[29] Ethnic cleansing reduced the numbers of other groups. Serb police, soldiers, and irregulars attacked Bosniaks and Croats, and burned and looted their homes. Some were killed on the spot; others were rounded up and killed elsewhere, or forced to flee.[30]

The number of Croats was reduced by 135,386 (the majority of the pre-war population), and the number of Bosniaks by some 434,144. Some 136,000 of approximately 496,000 Bosniak refugees forced to flee the territory of what is now Republika Srpska have returned home.[31]

As of 2008, 35% of Bosniaks and 8.5% of Croats had returned to Republika Srpska, while 24% of Serbs who left their homes in territories controlled by Bosniaks or Croats, had returned to their pre-war communities.[32]

In the early 2000s, discrimination against non-Serbs was alleged by NGOs and the Helsinki Commission. The International Crisis Group reported in 2002 that in some parts of Republika Srpska a non-Serb returnee is ten times more likely to be the victim of violent crime than is a local Serb.[33] The Helsinki Commission, in a 2001 statement on "Tolerance and Non-Discrimination", pointed at violence against non-Serbs, stating that in the cities of Banja Luka[34] and Trebinje,[35] mobs attacked people who sought to lay foundations for new mosques.

Non-Serbs have reported continuing difficulties in returning to their original homes and the assembly has a poor record of cooperation in apprehending individuals indicted for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.[36]

Organizations such as the Society for Threatened Peoples, reporting to the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2008, have made claims of discrimination against non-Serb refugees in the Republika Srpska, particularly areas with high unemployment in the Drina Valley such as Srebrenica, Bratunac, Višegrad, and Foča. Separate schools for Croats and non-Croats were formed, and ethnic Croat students are taught using a Croatian curriculum, whereas Serb and Bosniak pupils are taught according to the curriculum prescribed by the federal government.[37]

According to the Ministry for Human Rights and Refugees of Bosnia and Herzegovina, European Union Police Mission, UNHCR, and other international organizations, security in both Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is at present satisfactory, although some minor threats, real or perceived, can still influence the decision of individuals as to whether they will return to their pre-war addresses or not.[32]

Geography

Boundary

The Inter-Entity Boundary Line (IEBL) between Bosnia and Herzegovina's two entities essentially follows the front lines at the end of the Bosnian War with adjustments (most importantly in the western part of the country and around Sarajevo) defined by the Dayton Agreement. The total length of the IEBL is approximately 1,080 km. The IEBL is an administrative demarcation uncontrolled by military or police and there is free movement across it.

Municipalities

Under the Law on Territorial Organization and Local Self-Government, adopted in 1994, Republika Srpska was divided into 80 municipalities. After the Dayton Peace Agreement the law was amended to reflect changes to borders: it now comprises 63 municipalities.

The largest cities in Republika Srpska are (2013 census):[3]

- Banja Luka, population 199,191

- Bijeljina, population 114,663

- Prijedor, population 97,588

- Doboj, population 77,223

- Istočno Sarajevo, population 64,966

- Zvornik, population 63,686

- Gradiška, population 56,727

- Teslić, population 41,904

- Prnjavor, population 38,399

- Laktaši, population 36,848

- Trebinje, population 31,433

- Derventa, population 30,177

- Modriča, population 27,799

- Kozarska Dubica, population 23,074

- Foča, population 12,334

Mountains

The Dinaric Alps dominate the western border with Croatia. Mountains in Republika Srpska include Kozara, Romanija, Jahorina, Bjelašnica, Motajica and Treskavica. The highest point of the entity is peak Maglić at 2,386 m, near the border with Montenegro.

Hydrology

Most rivers belong to the Black Sea drainage basin. The principal rivers are the Sava, a tributary of the Danube that forms the northern boundary with Croatia; the Bosna, Vrbas, Sana and Una, which flow north and empty into the Sava; the Drina, which flows north, forms part of the eastern boundary with Serbia, and is also a tributary of the Sava. Trebišnjica is one of the longest sinking rivers in the world. It belongs Adriatic Sea drainage basin. Skakavac Waterfall on the Perućica is one of the highest waterfalls in the country, at about 75 metres (246 ft) in height. The most important lakes are Bileća Lake, Lake Bardača and Balkana Lake.

Protected areas

In Republika Srpska are located two national parks, Sutjeska National Park and Kozara National Park, and one protected nature park, Bardača. Perućica is one of the last remaining primeval forests in Europe.[38]

Demography

The first post-war census was the 2013 population census in Bosnia and Herzegovina, earlier figures are estimates.

| Year | Total | Males | Females | Births | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 1,391,593 | 12,263 | 10,931 | ||

| 1997 | 1 409 835 | 13,757 | 11,755 | ||

| 1998 | 1,428,798 | 679,795 | 749,003 | 13,527 | 12,469 |

| 1999[note 1] | 1,448,579 | 689,186 | 759,351 | ||

| 2000[note 1] | 1,469,182 | 14,191 | 13,370 | ||

| 2000 | 1,428,899 | 695,194 | 733,705 | ||

| 2001[note 1] | 1,490,993 | 13,699 | 13,434 | ||

| 2001 | 1,447,477 | 704,197 | 743,280 | ||

| 2002 | 1,454,802 | 708,136 | 746,666 | 12,336 | 12,980 |

| 2003 | 1,452,351 | 706,925 | 745,426 | 10,537 | 12,988 |

| 2004 | 1,449,897 | 705,731 | 744,166 | 10,628 | 13,082 |

| 2005 | 1,446,417 | 704,037 | 742,380 | 10,322 | 13,802 |

| 2006 | 1,443,709 | 702,718 | 740,991 | 10,524 | 13,232 |

| 2007 | 1,439,673 | 700,754 | 738,919 | 10,110 | 14,146 |

| 2008 | 1,437,477 | 699,685 | 737,792 | 10,198 | 13,501 |

| 2009 | 1,435,179 | 698,567 | 736,612 | 10,603 | 13,775 |

| 2010 | 1,433,038 | 697,524 | 735,514 | 10,147 | 13,517 |

| 2011 | 1,429,668 | 695,884 | 733,784 | 9,561 | 13,658 |

| 2012 | 1,425,571 | 9,978 | 13,796 | ||

| 2013 | 1,326,991(2013 census) | 9,510 | 13,978 |

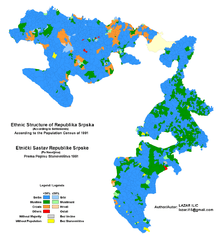

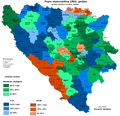

Ethnic composition

| Ethnic Composition | |||||||||||||

| Year | Serbs | % | Muslims | % | Croats | % | Yugoslavs | % | Others | % | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991[40] | 869,854 | 55.4 | 440,746 | 28.1 | 144,238 | 9.2 | 75,013 | 4.8 | 39,481 | 2.5 | 1,569,332 | ||

-

thnic composition in 1895 (census)

-

Ethnic composition in 1981(census)

-

Ethnic composition in 1991 (census)

-

Ethnic composition in 2006 (estimate)

| Largest cities of Republika Srpska (2013 census) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | City | Municipality | Urban population | |||||||

| 1 | Banja Luka | City of Banja Luka | 199,191 | |||||||

| 2 | Bijeljina | City of Bijeljina | 114,663 | |||||||

| 3 | Prijedor | City of Prijedor | 97,588 | |||||||

| 5 | Doboj | City of Doboj | 77,223 | |||||||

| 4 | Istočno Sarajevo | City of Istočno Sarajevo | 76,569 | |||||||

| 7 | Zvornik | Municipality Zvornik | 63,386 | |||||||

| 6 | Gradiška | Municipality Gradiška | 56,727 | |||||||

| 8 | Teslić | Municipality Teslić | 41,904 | |||||||

| 10 | Prnjavor | Municipality Prnjavor | 38,399 | |||||||

| 9 | Trebinje | City of Trebinje | 37,385 | |||||||

| 11 | Derventa | Municipality Derventa | 30,177 | |||||||

| 12 | Foča | Municipality Foča | 29,811 | |||||||

Economy

The currency of Republika Srpska is the Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark (KM). It takes a minimum of 23 days to register a business there, whereas in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina it often takes several months. Gross domestic product (PPP) was estimated in 2010 at about US$7,895 per capita, but growth in the particular area was measured as being the highest in Bosnia, with 6,5%.[42]

| GDP of Republika Srpska 2006–2011 (mil. KM)[43] | |||||||||||||||

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,373 | 3,666 | 4,208 | 4,560 | 5,116 | 5,763 | 6,546 | 7,352 | 8,490 | 8,236 | 8,318 | 8,682 | 8,584 | 8,760 | 8,831 | |

| Participation in total BiH economy | |||||||||||||||

| 28.54% | 28.92% | 30.10% | 30.98% | 31.98% | 33.47% | 33.56% | 33.44% | 34.10% | 33.98% | 33.54% | 33.78% | 33.36% | 33,32% | 32.66% | |

Foreign investment

An agreement on strategic partnership has been concluded between the Iron Ore Mine Ljubija Prijedor and the British company LNM (a major steel producer, now part of ArcelorMittal). Russia's Yuzhuralzoloto Gruppa Kompaniy OAO signed a strategic partnership with the Lead and Zinc Mine Sase Srebrenica. Recent foreign investments include privatisation of Telekom Srpske, sold to the Serbian Telekom Srbija for €646 million, and the sale of the petroleum and oil industry, based in Bosanski Brod, Modriča and Banja Luka, to Zarubezhneft of Russia, whose investment is expected to total US$970 million in coming years.[44]

On 16 May 2007, the Czech power utility ČEZ signed a €1.4 billion contract with the Elektroprivreda Republike Srpske, to renovate the Gacko I power plant and build a second, Gacko II.[45]

As of September 2012, the President of Republika Srpska, Milorad Dodik, has signed an agreement with the Russian company Gazprom to build a part of the South Stream pipeline network and two gas power plants in the entity.[46]

External trade

| External trade of Republika Srpska (mil. euros) (not including trade with the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Brčko District)[47][48][49] | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | 306 | 289 | 312 | 431 | 578 | 788 | 855 | 983 | 855 | 1,114 | 1,309 | 1,214 | 1,331 |

| Imports | 868 | 1,107 | 1,165 | 1,382 | 1,510 | 1,411 | 1,712 | 2,120 | 1,825 | 2,072 | 2,340 | 2,294 | 2,330 |

| Total trade | 1,174 | 1,396 | 1,477 | 1,813 | 2,088 | 2,199 | 2,567 | 3,103 | 2,680 | 3,186 | 3,649 | 3,508 | 3,662 |

| Coverage (%) | 35 | 26 | 27 | 31 | 38 | 56 | 50 | 46 | 47 | 54 | 56 | 53 | 57 |

Taxation and salaries

Since 2001, Republika Srpska initiated significant reforms in the sector of the tax system, which lowered the tax burden to 28.6%, one of the lowest in the region. The 10% rate of capital gains tax and income tax are among the lowest in Europe and highly stimulating for foreign investment, and there are no limits on the amount of earnings. Increasing the number of taxpayers and budgeted incomes, and creating a stable fiscal system, were necessary for further reforms in the fields of taxation and duties; this area is a priority goal of the RS authorities. VAT has been introduced in 2006. Income tax is 46% in the RS, compared to nearly 70% in the Federation, and the corporate tax rate is 10%, compared to 30% in the Federation. These tax advantages have led to some companies moving their business to RS from the other entity.[42]

Republika Srpska saw accelerated salary growth in 2008. The average net salary in 2008 amounted to KM 755 (€386), which represents an increase of 29% compared to 2007 average. High inflation rate in 2008 caused the difference between the nominal and the real salary growth to be higher than in 2007. Average net salaries in Republika Srpska saw a real growth of 21.8%, since 2008 inflation measured by Consumer Price Index was 7.2%. Marked salary growth was particularly contributed to by salary growth in individual economic sectors, especially in public sector. Regarding pensions in Republika Srpska, their growth in 2008 kept pace with salary trends. The average pension in 2008 amounted to KM 294 (€150), which is larger by 27.8% (y/y). Somewhat higher pension growth in the RS might be explained by significantly faster growth of contributions of the PDI Fund. The average wage as of January 2013 stood at KM 810.0 (€415).

Politics

According to its constitution, Republika Srpska has its own president, people's assembly (the 83-member unicameral People's Assembly of Republika Srpska), executive government (with a prime minister and several ministries), its own police force, supreme court and lower courts, customs service (under the state-level customs service), and a postal service. It also has its symbols, including coat of arms, flag (a variant of the Serbian flag without the coat of arms displayed) and entity anthem. The Constitutional Law on Coat of Arms and Anthem of the Republika Srpska was ruled not in concordance with the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina as it states that those symbols "represent statehood of the Republika Srpska" and are used "in accordance with moral norms of the Serb people". According to the Constitutional Court's decision, the Law was to be corrected by September 2006.

Although the constitution names Sarajevo as the capital of Republika Srpska, the northwestern city of Banja Luka is the headquarters of most of the institutions of government, including the parliament, and is therefore the de facto capital. After the war, Republika Srpska retained its army, but in August 2005, the parliament consented to transfer control of Army of Republika Srpska to a state-level ministry and abolish the entity's defense ministry and army by 1 January 2006. These reforms were required by NATO as a precondition of Bosnia and Herzegovina's admission to the Partnership for Peace programme. Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the programme in December 2006.

External relations

In September 2006, Republika Srpska officials signed a "special ties agreement" with Serbia aimed at promoting economic and institutional cooperation between Serbia and Republika Srpska (RS). The accord was signed by Serbia's President Boris Tadić and Prime Minister Vojislav Koštunica, former RS President Dragan Čavić, and RS Prime Minister Milorad Dodik. Tadić and Koštunica, accompanied by several ministers and some 300 businessmen, arrived in Banja Luka on two special planes from Belgrade, in what was seen as the biggest-ever boost to strengthening ties in all spheres of life between the Republika Srpska and Serbia. The Serbian Komercijalna banka and the Dunav osiguranje insurance company opened branches in Banja Luka and the Serbian news agency Tanjug also inaugurated its international press center in Banja Luka.

The document set out steps taken by Serbia and Republika Srpska officials to increase economic and political ties. It is similar to a previous one signed in 2001 between the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Republika Srpska, which envisaged close cooperation in matters of economy, defense, education, as well as allowing for dual citizenship for the residents of RS, according to a statement released by Serbian government.

The agreement gives Republika Srpska, the same status in relation to Serbia as the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole. "This agreement will stabilize the relations between countries in the region and it will promote economic, political, and cultural relations between Serbia and Republika Srpska", Čavić told reporters after the signing ceremony. Koštunica added "We have long waited for this day", and insisting that the agreement would not be "a dead letter on paper", but would "live and be useful to the citizens of Serbia and Republika Srpska".

Representative offices

In February 2009, Republika Srpska opened a representative office in Brussels. While European Union representatives were not present at the ceremony, top Republika Srpska officials attended the event, saying it would advance their economic, political and cultural relations with the EU. This notion has been strongly condemned by Bosniak leaders, saying that this is further proof of Republika Srpska distancing itself from Bosnia and Herzegovina. The president of Republika Srpska, Rajko Kuzmanović, told reporters that this move did not jeopardise Republika Srpska's place within Bosnia and Herzegovina. He added that Republika Srpska merely used its constitutional right "to open up a representation office in the center of developments of European relevance". Republika Srpska maintains official offices in Belgrade, Moscow, Stuttgart, Jerusalem, Thessaloniki, Washington D.C., Brussels, and Vienna.[51][52][53]

Holidays

According to the Law on Holidays of Republika Srpska, public holidays are divided into three categories: entity's holidays, religious holidays, and holidays which are marked but do not include time off work. The entity holidays include New Year's Day (1 January), Entity Day (9 January), International Workers' Day (1 May), Victory over Fascism Day (9 May) and Day of the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina (21 November).[54]

Religious holidays include Christmas and Easter according to both the Julian and the Gregorian calendars for, respectively, Serbian Orthodox Christians and Roman Catholics, as well as Kurban Bajram and Bajram for Muslims. Holidays which are marked but do not include time off work include School Day (the Feast of Saint Sava, 27 January), Day of the Army of the Republika Srpska (12 May), Interior Ministry Day (4 April), and Day of the First Serbian Uprising (14 February).[54]

The most important of the entity holidays is Dan Republike, which commemorates the establishment of Republika Srpska on 9 January 1992. It coincides with Saint Stephen's Day according to the Julian calendar. The Orthodox Serbs also refer to the holiday as the Slava of Republika Srpska, as they regard Saint Stephen as the patron saint of Republika Srpska. The holiday has therefore a religious dimension, being celebrated with special services in Serbian Orthodox churches.[55] Republika Srpska does not recognize the Independence Day of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1 March).[56]

Culture

Education

The oldest and largest public university in Republika Srpska is University of Banja Luka established in 1975. The second of two public universities in Republika Srpska is University of East Sarajevo. After the end of the Yugoslav wars several private institutions of higher education were established, including: American University in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slobomir University and University Sinergija. The Academy of Sciences and Arts of the Republika Srpska is the highest representative institution in the Republika Srpska of science and art founded in 1996. National and University Library of the Republika Srpska is a national library, located in Banja Luka. The Museum of Contemporary Art (MSURS) houses a collection of Yugoslav and international art and is located in Banja Luka.

Sport

Sport revolves mostly around team sports. Among the most popular sports are football, basketball, volleyball, handball and tennis. The main football clubs in Republika Srpska are FK Borac Banja Luka, FK Leotar, FK Slavija, FK Rudar Prijedor and the others. Banja Luka is one of the most famous handball centers in the Balkans. RK Borac Banja Luka won the European Champions' Cup in 1976. and EHF Cup in 1991. RK Borac Banja Luka players have won 6 Gold Olympic medals for former Yugoslavia. Notable sportspeople born in what is now Republika Srpska include footballers Tomislav Knez, Velimir Sombolac, Mehmed Baždarević and Milena Nikolić; handball players Đorđe Lavrnić, Milorad Karalić, Nebojša Popović, Zlatan Arnautović and Danijel Šarić; basketball players Ratko Radovanović, Slađana Golić and Nihad Đedović; boxers Anton Josipović, Slobodan Kačar and Tadija Kačar; table tennis player Jasna Fazlić; shot putter Hamza Alić; and taekwondo practitioner Zoran Prerad.

Gallery

-

Monument of Petar I of Serbia in Bijeljina

-

Hercegovačka Gračanica (Trebinje)

-

University in Bijeljina

-

Mount Jahorina

-

View from Doboj Fortress

-

Romanija

-

Banski dvor

-

Palata Republike

-

Ethnos village, Bijeljina

-

Arslanagića bridge in Trebinje

-

National park Sutjeska

-

Trnovačko Lake

Notes

References

- ↑ (Serbian) Srpska – Portal javne uprave Republike Srpske: Simboli at the Government of Republika Srpska official website (retrieved 17 May 2012).

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republika Srpska-Official Web Site of the Office of the High Representative".

- 1 2 "Preliminary Results of the 2013 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Bosnia and Herzegovina" (PDF). Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina. 5 November 2013.

- ↑ "Decision on Constitutional Amendments in Republika Srpska". Office of the High Representative. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ↑ "Bosnia-Hercegovina profile". BBC. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Related Articles. "Serb Republic (region, Bosnia and Herzegovina) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "Bosnian Serb republic leader dies". BBC News. 30 September 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ Moss, Paul (27 June 2009). "Bosnia echoes to alarming rhetoric". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ Lyon, James (4 December 2009). "Halting the downward spiral". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ Beaumont, Peter (3 May 2009). "Bosnia lurches into a new crisis". The Guardian (London, UK). Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ Pressrs.ba (20 July 2014). "Srpska is more sovereign than Serbia" (in Serbian). Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Silber, Laura (16 October 1991). "Bosnia Declares Sovereignty". The Washington Post: A29. ISSN 0190-8286.

- ↑ Kecmanović, Nenad. "Dayton Is Not Lisbon". NIN. ex-yupress.comex-yupress.comex-yupress.com. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- 1 2 "The Decision on Establishment of the Assembly of the Serb People in Bosnia and Herzegovina". Official Gazette of the Serb People in Bosnia and Herzegovina (in Serbian) 1 (1): 1. 15 January 1992.

- ↑ Women, violence, and war: wartime ... Google Books. 2000. ISBN 978-963-9116-60-3. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "The Declaration of Proclamation of the Republic of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina". Official Gazette of the Serb People in Bosnia and Herzegovina (in Serbian) 1 (2): 13–14. 27 January 1992.

- ↑ "The Constitution of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina". Official Gazette of the Serb People in Bosnia and Herzegovina (in Serbian) 1 (3): 17–26. 16 March 1992.

- ↑ Kreća, Milenko (11 July 1996). "The Legality of the Proclamation of Bosnia and Herzegovina's Independence in Light of the Internal Law of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia" and "The Legality of the Proclamation of Independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Light of International Law" in "Dissenting Opinion of Judge Kreća" (PDF). Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1996 (The Hague: The Registry of the International Court of Justice): pp. 711–47. ISSN 0074-4441

- ↑ Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian. The Balkans: A Post-Communist History (2007, New York: Routledge), p. 343

- ↑ Saving strangers: humanitarian. Google Books. 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-829621-8. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "The Decision on Proclamation of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina". Večernje novosti (in Serbian) (Belgrade: Novosti AD). Tanjug. 8 April 1992. ISSN 0350-4999.

- ↑ "The Amendments VII and VIII to the Constitution of the Republika Srpska". Official Gazette of the Republika Srpska (in Serbian) 1 (15): 569. 29 September 1992.

- ↑ "Prosecutor v. Radovan Karadžić – Second Amended Indictment" (PDF). UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 26 February 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ↑ "Prosecutor v. Ratko Mladić – Amended Indictment" (PDF). UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 8 November 2002. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ↑ "The General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina". OHR.int. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ↑ "Constitution of Republika Srpska". The Constitutional Court of Republika Srpska. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ UNESCO (1998). "Review of the education system in the Republika Srpska". Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ↑ The World Factbook, cia.gov; accessed 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Press Online Republika Srpska: Od pola miliona, u FBiH ostalo 50.000 Srba, pressrs.ba; accessed 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Judah. The Serbs. Yale University Press. pp. 225–41. ISBN 978-0-300-15826-7.

- ↑ "Written statement submitted by the Society for Threatened Peoples to the Commission of Human Rights; Sixtieth session Item 11 (d) of the provisional agenda". United Nations. 26 February 2004. p. 2. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- 1 2 Revidirana strategija Bosne i Hercegovine za provedbu Aneksa VII Dejtonskog mirovnog sporazuma. Ministry for Human Rights and Refugees of Bosnia and Herzegovina (mhrr.gov.ba), October 2008; accessed 13 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Continuing Challenge of Refugee Return in Bosnia & Herzegovina". Crisis Group. 13 December 2002.

- ↑ "UN Condemns Serb 'Sickness'". BBC. 8 May 2001. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ "Serbs Block Bosnia Mosque Ceremony". BBC. 6 May 2001. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ "Helsinki Commission Releases U.S. Statement on Tolerance and Non-Discrimination at OSCE Human Dimension Implementation Meeting". Helsinki Commission. 20 September 2001. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "7th Session of the UN Human Rights Council" (PDF). Society for Threatened Peoples. 21 February 2008. p. 2.

- ↑ Perućica Official website, npsutjeska.net; accessed 24 November 2015.

- ↑ "Republika Srpska in Figures 2009" (PDF). Banja Luka: Republika Srpska Institute of Statistics. 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ Federation Office of Statistics (May 2008). "Population of the Federation Bosnia and Herzegovina 1996 – 2006", p. 20,

- ↑ Employment, unemployment and wages Statistical Yearbook of Republika Srpska 2014

- 1 2 Kampschror, Beth (15 May 2007). "Bosnian Territory Opens Doors for Business". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- ↑ Baza podataka o ekonomskim indikatorima Republike Srpske – IRBRS

- ↑ "Investicija za preporod privrede BiH". Nezavisine novine. 25 January 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2007.

- ↑ "CEZ signs contract on energy project in Bosnia". Prague Daily Monitor. 17 May 2007. Archived from the original on 21 May 2007. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- ↑ Bosnia's Serb Entity Signs up for South Stream Pipeline, balkaninsight.com; accessed 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Статистички годишњак 2012, rzs.rs.ba; accessed 8 April 2015.

- ↑ http://www.rzs.rs.ba/front/article/332/?left_mi=None&add=None

- ↑ EXTERNAL TRADE OF REPUBLIKA SRPSKA (IMPORT AND EXPORT)

- ↑ rzs.rs.ba/Publikacije/Godisnjak/2011

- ↑ Представништва Републике Српске у иностранству, vladars.net; accessed 31 October 2015.(Serbian)

- ↑ U Beču otvoreno Predstavništvo Republike Srpske, biznis.ba; accessed 3 August 2015.(Serbian)

- ↑ Dodik otvorio predstavništvo Republike Srpske u Beču, smedia.rs; accessed 3 August 2015.(Serbian)

- 1 2 "Zakon o praznicima Republike Srpske". Zakoni (in Serbian). People's Assembly of Republika Srpska. 27 July 2005. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ↑ Прослављена слава Републике Српске – Свети архиђакон Стефан (in Serbian). The Serbian Orthodox Church. 9 January 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ↑ RS ne priznaje Dan nezavisnosti BiH, b92.net; accessed 3 August 2015.(Serbian)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Republika Srpska. |

- Government of Republika Srpska

- President of Republika Srpska

- People's Assembly of Republika Srpska

- RS Institute of Statistics

- The Constitution of Republika Srpska official document

- Relevant laws of Republika Srpska

- Republika Srpska ~ Moja Republika

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|