Dolphin

| Dolphins | |

|---|---|

| Dolphins are not a taxon, they are an informal grouping of the infraorder Cetacea | |

|

Bottlenose dolphin | |

| Information | |

| Classification of Cetacea |

|

| Families thought of as dolphins | |

Dolphins are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic marine mammals. They are an informal grouping within the order Cetacea, excluding whales and porpoises, so to zoologists the grouping is paraphyletic. The dolphins comprise the extant families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the new world river dolphins), and Pontoporiidae (the brackish dolphins). There are 40 extant species of dolphins. Dolphins, alongside other cetaceans, belong to the clade Cetartiodactyla with even-toed ungulates, and their closest living relatives are the hippopotamuses, having diverged about 40 million years ago.

Dolphins range in size from the 1.7 metres (5.6 ft) long and 50 kilograms (110 lb) Maui's dolphin to the 9.5 metres (31 ft) and 10 metric tons (11 short tons) killer whale. Several species exhibit sexual dimorphism, in that the males are larger than females. They have streamlined bodies and two limbs that are modified into flippers. Though not quite as flexible as seals, some dolphins can travel at 55.5 kilometres per hour (34.5 mph). Dolphins use their conical shaped teeth to capture fast moving prey. They have well-developed hearing − their hearing, which is adapted for both air and water, is so well developed that some can survive even if they are blind. Some species are well adapted for diving to great depths. They have a layer of fat, or blubber, under the skin to keep warm in the cold water.

Although dolphins are widespread, most species prefer the warmer waters of the tropic zones, but some, like the right whale dolphin, prefer colder climates. Dolphins feed largely on fish and squid, but a few, like the killer whale, feed on large mammals, like seals. Male dolphins typically mate with multiple females every year, but females only mate every two to three years. Calves are typically born in the spring and summer months and females bear all the responsibility for raising them. Mothers of some species fast and nurse their young for a relatively long period of time. Dolphins produce a variety of vocalizations, usually in the form of clicks and whistles.

Dolphins are sometimes hunted in places like Japan, in an activity known as dolphin drive hunting. Besides drive hunting, they also face threats from bycatch, habitat loss, and marine pollution. Dolphins have been depicted in various cultures worldwide. Dolphins occasionally feature in literature and film, as in the Warner Bros film Free Willy. Dolphins are sometimes kept in captivity and trained to perform tricks, but breeding success has been poor and the animals often die within a few months of capture. The most common dolphins kept are the killer whales and bottlenose dolphins.

Etymology

The name is originally from Greek δελφίς (delphís), "dolphin",[1] which was related to the Greek δελφύς (delphus), "womb".[1] The animal's name can therefore be interpreted as meaning "a 'fish' with a womb".[2] The name was transmitted via the Latin delphinus[3] (the romanization of the later Greek δελφῖνος – delphinos[1]), which in Medieval Latin became dolfinus and in Old French daulphin, which reintroduced the ph into the word. The term mereswine (that is, "sea pig") has also historically been used.[4]

The term 'dolphin' can be used to refer to, under the suborder Odontoceti, all the species in the family Delphinidae (oceanic dolphins) and the river dolphin families Iniidae (South American river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (La Plata dolphin), Lipotidae (Yangtze river dolphin) and Platanistidae (Ganges river dolphin and Indus river dolphin).[5][6] This term has often been misused in the US, mainly in the fishing industry, where all small cetaceans (dolphins and porpoises) are considered porpoises,[7] while the fish dorado is called dolphin fish.[8] In common usage the term 'whale' is used only for the larger cetacean species,[9] while the smaller ones with a beaked or longer nose are considered 'dolphins'.[10] The name 'dolphin' is used casually as a synonym for bottlenose dolphin, the most common and familiar species of dolphin.[11] There are six species of dolphins commonly thought of as whales, collectively known as blackfish: the killer whale, the melon-headed whale, the pygmy killer whale, the false killer whale, and the two species of pilot whales, all of which are classified under the family Delphinidae and qualify as dolphins.[12] Though the terms 'dolphin' and 'porpoise' are sometimes used interchangeably, porpoises are not considered dolphins and have different physical features such as a shorter beak and spade-shaped teeth; they also differ in their behavior. Porpoises belong to the family Phocoenidae and share a common ancestry with the Delphinidae.[11]

A group of dolphins is called a "school" or a "pod". Male dolphins are called "bulls", females "cows" and young dolphins are called "calves".[13]

Taxonomy

- Suborder Odontoceti, toothed whales

- Family Platanistidae

- Ganges and Indus river dolphin, Platanista gangetica with two subspecies

- Ganges river dolphin (or Susu), Platanista gangetica gangetica

- Indus river dolphin (or Bhulan), Platanista gangetica minor

- Ganges and Indus river dolphin, Platanista gangetica with two subspecies

- Family Iniidae

- Amazon river dolphin (or Boto), Inia geoffrensis

- Orinoco river dolphin (the Orinoco subspecies), Inia geoffrensis humboldtiana

- Araguaian river dolphin (Araguaian boto), Inia Araguaiaensis

- Bolivian river dolphin, Inia boliviensis

- Amazon river dolphin (or Boto), Inia geoffrensis

- Family Lipotidae

- Baiji (or Chinese river dolphin), Lipotes vexillifer (possibly extinct, since December 2006)

- Family Pontoporiidae

- La Plata dolphin (or Franciscana), Pontoporia blainvillei

- Family Delphinidae, oceanic dolphins

- Genus Delphinus

- Long-beaked common dolphin, Delphinus capensis

- Short-beaked common dolphin, Delphinus delphis

- Genus Tursiops

- Common bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops truncatus

- Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops aduncus

- Burrunan dolphin, Tursiops australis, a newly discovered species from the sea around Melbourne in September 2011.[14]

- Genus Lissodelphis

- Northern right whale dolphin, Lissodelphis borealis

- Southern right whale dolphin, Lissodelphis peronii

- Genus Sotalia

- Genus Sousa

- Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin, Sousa chinensis

- Chinese white dolphin (the Chinese variant), Sousa chinensis chinensis

- Atlantic humpback dolphin, Sousa teuszii

- Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin, Sousa chinensis

- Genus Stenella

- Atlantic spotted dolphin, Stenella frontalis

- Clymene dolphin, Stenella clymene

- Pantropical spotted dolphin, Stenella attenuata

- Spinner dolphin, Stenella longirostris

- Striped dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba

- Genus Steno

- Rough-toothed dolphin, Steno bredanensis

- Genus Cephalorhynchus

- Chilean dolphin, Cephalorhynchus eutropia

- Commerson's dolphin, Cephalorhynchus commersonii

- Haviside's dolphin, Cephalorhynchus heavisidii

- Hector's dolphin, Cephalorhynchus hectori

- Genus Grampus

- Risso's dolphin, Grampus griseus

- Genus Lagenodelphis

- Fraser's dolphin, Lagenodelphis hosei

- Genus Lagenorhynchus

- Atlantic white-sided dolphin, Lagenorhynchus acutus

- Dusky dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obscurus

- Hourglass dolphin, Lagenorhynchus cruciger

- Pacific white-sided dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obliquidens

- Peale's dolphin, Lagenorhynchus australis

- White-beaked dolphin, Lagenorhynchus albirostris

- Genus Orcaella

- Australian snubfin dolphin, Orcaella heinsohni

- Irrawaddy dolphin, Orcaella brevirostris

- Genus Peponocephala

- Melon-headed whale, Peponocephala electra

- Genus Orcinus

- Killer whale (Orca), Orcinus orca

- Genus Feresa

- Pygmy killer whale, Feresa attenuata

- Genus Pseudorca

- False killer whale, Pseudorca crassidens

- Genus Globicephala

- Long-finned pilot whale, Globicephala melas

- Short-finned pilot whale, Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Genus †Australodelphis

- Genus Delphinus

- Family Platanistidae

- Six species in the family Delphinidae are commonly called "whales", but genetically are dolphins. They are sometimes called blackfish.

- Melon-headed whale, Peponocephala electra

- Killer whale (Orca), Orcinus orca

- Pygmy killer whale, Feresa attenuata

- False killer whale, Pseudorca crassidens

- Long-finned pilot whale, Globicephala melas

- Short-finned pilot whale, Globicephala macrorhynchus

Hybridization

In 1933, three strange dolphins beached off the Irish coast; they appeared to be hybrids between Risso's and bottlenose dolphins.[15] This mating was later repeated in captivity, producing a hybrid calf. In captivity, a bottlenose and a rough-toothed dolphin produced hybrid offspring.[16] A common-bottlenose hybrid lives at SeaWorld California.[17] Other dolphin hybrids live in captivity around the world or have been reported in the wild, such as a bottlenose-Atlantic spotted hybrid.[18] The best known hybrid is the wolphin, a false killer whale-bottlenose dolphin hybrid. The wolphin is a fertile hybrid. Two wolphins currently live at the Sea Life Park in Hawaii; the first was born in 1985 from a male false killer whale and a female bottlenose. Wolphins have also been observed in the wild.[19]

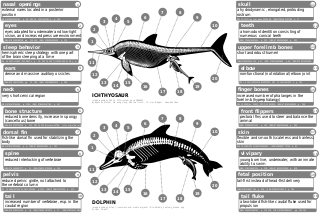

Evolution

Dolphins are descendants of land-dwelling mammals of the artiodactyl order (even-toed ungulates). They are related to the Indohyus, an extinct chevrotain-like ungulate, from which they split approximately 48 million years ago.[20][21] The primitive cetaceans, or archaeocetes, first took to the sea approximately 49 million years ago and became fully aquatic by 5–10 million years later.[22]

Archaeoceti is a parvorder comprising ancient whales. These ancient whales are the predecessors of modern whales, stretching back to their first ancestor that spent their lives near (rarely in) the water. Likewise, the archaeocetes can be anywhere from near fully terrestrial, to semi-aquatic to fully aquatic, but what defines an archaeocete is the presence of visible legs or asymmetrical teeth.[23][24][25][26] Their features became adapted for living in the marine environment. Major anatomical changes include the hearing set-up that channeled vibrations from the jaw to the earbone which occurred with Ambulocetus 49 million years ago, a streamlining of the body and the growth of flukes on the tail which occurred around 43 million years ago with Protocetus, the migration of the nasal openings toward the top of the cranium and the modification of the forelimbs into flippers which occurred with Basilosaurus 35 million years ago, and the shrinking and eventual disappearance of the hind limbs which took place with the first odontocetes and mysticetes 34 million years ago.[27][28][29] The modern dolphin skeleton has two small, rod-shaped pelvic bones thought to be vestigial hind limbs. In October 2006, an unusual bottlenose dolphin was captured in Japan; it had small fins on each side of its genital slit, which scientists believe to be an unusually pronounced development of these vestigial hind limbs.[30]

Today, the closest living relatives of cetaceans are the hippopotamuses; these share a semi-aquatic ancestor that branched off from other artiodactyls some 60 million years ago.[31] Around 40 million years ago, a common ancestor between the two branched off into cetacea and anthracotheres; anthracotheres went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene two-and-a-half million years ago, eventually leaving only one surviving lineage: the hippo.[32][33]

Biology

Anatomy

Dolphins have torpedo shaped bodies with non-flexible necks, limbs modified into flippers, non-existent external ear flaps, a tail fin, and bulbous heads. Dolphin skulls have small eye orbits, long snouts, and eyes placed on the sides of its head. Dolphins range in size from the 1.7 metres (5.6 ft) long and 50 kilograms (110 lb) Maui's dolphin to the 9.5 metres (31 ft) and 10 metric tons (11 short tons) killer whale. Overall, however, they tend to be dwarfed by other Cetartiodactyls. Several species have female-biased sexual dimorphism, with the females being larger than the males.[34][35]

Dolphins have conical shape teeth, as apposed to their counterparts, porpoise's, spade-shaped teeth. These conical teeth are used to catch swift prey such as fish, squid or large mammals, such as seal.[35]

Breathing involves expelling stale air from their blowhole, forming an upward, steamy spout, followed by inhaling fresh air into the lungs, however this only occurs in the polar regions of the oceans. Dolphins have rather small, unidentifiable spouts.[35][36]

All dolphins have a thick layer of blubber, thickness varying on climate. This blubber can help with buoyancy, protection to some extent as predators would have a hard time getting through a thick layer of fat, and energy for leaner times; the primary usage for blubber is insulation from the harsh climate. Calves, generally, are born with a thin layer of blubber, which develops at different paces depending on the habitat.[35][37]

Dolphins have a two-chambered stomach that is similar in structure to terrestrial carnivores. They have fundic and pyloric chambers.[38]

Locomotion

Dolphins have two flippers on the underside toward the head, a dorsal fin and a tail fin. These flippers contain four digits. Although dolphins do not possess fully developed hind limbs, some possess discrete rudimentary appendages, which may contain feet and digits. Dolphins are fast swimmers in comparison to seals who typically cruise at 9–28 kilometres per hour (5.6–17.4 mph); the killer whale, in comparison, can travel at speeds up to 55.5 kilometres per hour (34.5 mph). The fusing of the neck vertebrae, while increasing stability when swimming at high speeds, decreases flexibility, which means they are unable to turn their heads.[39][40] River dolphins, however, have non-fused neck vertebrae and are able to turn their head up to 90°.[41] Dolphins swim by moving their tail fin and rear body vertically, while their flippers are mainly used for steering. Some species log out of the water, which may allow them to travel faster. Their skeletal anatomy allows them to be fast swimmers. All species have a dorsal fin to prevent themselves from involuntarily spinning in the water.[35][37]

Some dolphins are adapted for diving to great depths. In addition to their streamlined bodies, some can slow their heart rate to conserve oxygen. Some can also re-route blood from tissue tolerant of water pressure to the heart, brain and other organs. Their hemoglobin and myoglobin store oxygen in body tissues and they have twice the concentration of myoglobin than hemoglobin.[42][43]

Senses

The dolphin ear has specific adaptations to the marine environment. In humans, the middle ear works as an impedance equalizer between the outside air's low impedance and the cochlear fluid's high impedance. In dolphins, and other marine mammals, there is no great difference between the outer and inner environments. Instead of sound passing through the outer ear to the middle ear, dolphins receive sound through the throat, from which it passes through a low-impedance fat-filled cavity to the inner ear. The dolphin ear is acoustically isolated from the skull by air-filled sinus pockets, which allow for greater directional hearing underwater.[44] Dolphins send out high frequency clicks from an organ known as a melon. This melon consists of fat, and the skull of any such creature containing a melon will have a large depression. This allows dolphins to produce biosonar for orientation.[35][45][46][47][48] Though most dolphins do not have hair, they do have hair follicles that may perform some sensory function.[49] Beyond locating an object, echolocation also provides the animal with an idea on an object's shape and size, though how exactly this works is not yet understood.[50] The small hairs on the rostrum of the Boto are believed to function as a tactile sense, possibly to compensate for the Boto's poor eyesight.[51]

The dolphin eye is relatively small for its size, yet they do retain a good degree of eyesight. As well as this, the eyes of a dolphin are placed on the sides of its head, so their vision consists of two fields, rather than a binocular view like humans have. When dolphins surface, their lens and cornea correct the nearsightedness that results from the refraction of light; they contain both rod and cone cells, meaning they can see in both dim and bright light, but they have far more rod cells than they do cone cells. Dolphins do, however, lack short wavelength sensitive visual pigments in their cone cells indicating a more limited capacity for color vision than most mammals.[52] Most dolphins have slightly flattened eyeballs, enlarged pupils (which shrink as they surface to prevent damage), slightly flattened corneas and a tapetum lucidum; these adaptations allow for large amounts of light to pass through the eye and, therefore, a very clear image of the surrounding area. They also have glands on the eyelids and outer corneal layer that act as protection for the cornea.[45]

The olfactory lobes are absent in dolphins, suggesting that they have no sense of smell.[45]

Dolphins are not thought to have a good sense of taste, as their taste buds are atrophied or missing altogether. However, some have preferences between different kinds of fish, indicating some sort of attachment to taste.[45]

Behavior

Dolphins are often regarded as one of Earth's most intelligent animals, though it is hard to say just how intelligent. Comparing species' relative intelligence is complicated by differences in sensory apparatus, response modes, and nature of cognition. Furthermore, the difficulty and expense of experimental work with large aquatic animals has so far prevented some tests and limited sample size and rigor in others. Compared to many other species, however, dolphin behavior has been studied extensively, both in captivity and in the wild. See cetacean intelligence for more details.

Social behavior

Dolphins are highly social animals, often living in pods of up to a dozen individuals, though pod sizes and structures vary greatly between species and locations. In places with a high abundance of food, pods can merge temporarily, forming a superpod; such groupings may exceed 1,000 dolphins. Membership in pods is not rigid; interchange is common. Dolphins can, however, establish strong social bonds; they will stay with injured or ill individuals, even helping them to breathe by bringing them to the surface if needed.[53] This altruism does not appear to be limited to their own species. The dolphin Moko in New Zealand has been observed guiding a female Pygmy Sperm Whale together with her calf out of shallow water where they had stranded several times.[54] They have also been seen protecting swimmers from sharks by swimming circles around the swimmers[55][56] or charging the sharks to make them go away.

Dolphins communicate using a variety of clicks, whistle-like sounds and other vocalizations. Dolphins also use nonverbal communication by means of touch and posturing.[57]

Dolphins also display culture, something long believed to be unique to humans (and possibly other primate species). In May 2005, a discovery in Australia found Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) teaching their young to use tools. They cover their snouts with sponges to protect them while foraging. This knowledge is mostly transferred by mothers to daughters, unlike simian primates, where knowledge is generally passed on to both sexes. Using sponges as mouth protection is a learned behavior.[58] Another learned behavior was discovered among river dolphins in Brazil, where some male dolphins use weeds and sticks as part of a sexual display.[59]

Forms of care-giving between fellows and even for members of different species[60] (see Moko (dolphin)) are recorded in various species - such as trying to save weakened fellows[61] or female pilot whales holding up dead calves for long periods.

Dolphins engage in acts of aggression towards each other. The older a male dolphin is, the more likely his body is to be covered with bite scars. Male dolphins engage in acts of aggression apparently for the same reasons as humans: disputes between companions and competition for females. Acts of aggression can become so intense that targeted dolphins sometimes go into exile after losing a fight.

Male bottlenose dolphins have been known to engage in infanticide. Dolphins have also been known to kill porpoises for reasons which are not fully understood, as porpoises generally do not share the same diet as dolphins and are therefore not competitors for food supplies.[62]

Reproduction and sexuality

Dolphins' reproductive organs are located on the underside of the body. Males have two slits, one concealing the penis and one further behind for the anus.[63] The female has one genital slit, housing the vagina and the anus. Two mammary slits are positioned on either side of the female's genital slit.[64][65][66]

Dolphin copulation happens belly to belly; though many species engage in lengthy foreplay, the actual act is usually brief, but may be repeated several times within a short timespan.[67] The gestation period varies with species; for the small Tucuxi dolphin, this period is around 11 to 12 months,[68] while for the orca, the gestation period is around 17 months.[69] Typically dolphins give birth to a single calf, which is, unlike most other mammals, born tail first in most cases.[70] They usually become sexually active at a young age, even before reaching sexual maturity.[67] The age of sexual maturity varies by species and gender.[71]

Dolphins are known to display non-reproductive sexual behavior, engaging in masturbation, stimulation of the genital area of other individuals using the rostrum or flippers, and homosexual contact.[67][72][73]

Male dolphins have been known to masturbate by wrapping a live eel around their penis.[74]

Various species of dolphin have been known to engage in sexual behavior up to and including copulation with dolphins of other species. Sexual encounters may be violent, with male dolphins sometimes showing aggressive behavior towards both females and other males.[75] Male dolphins may also work together and attempt to herd females in estrus, keeping the females by their side by means of both physical aggression and intimidation, to increase their chances of reproductive success.[76] Occasionally, dolphins behave sexually towards other animals, including humans.[77]

Feeding

Various methods of feeding exist among and within species, some apparently exclusive to a single population. Fish and squid are the main food, but the false killer whale and the orca also feed on other marine mammals. Orcas on occasion also hunt whale species larger than themselves.[78]

One common feeding method is herding, where a pod squeezes a school of fish into a small volume, known as a bait ball. Individual members then take turns plowing through the ball, feeding on the stunned fish.[78] Coralling is a method where dolphins chase fish into shallow water to catch them more easily.[78] Orcas and bottlenose dolphins have also been known to drive their prey onto a beach to feed on it, a behaviour known as beach or strand feeding.[79][80] Some species also whack fish with their flukes, stunning them and sometimes knocking them out of the water.[78]

Reports of cooperative human-dolphin fishing date back to the ancient Roman author and natural philosopher Pliny the Elder.[81] A modern human-dolphin partnership currently operates in Laguna, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Here, dolphins drive fish towards fishermen waiting along the shore and signal the men to cast their nets. The dolphins' reward is the fish that escape the nets.[82][83]

Vocalizations

Dolphins are capable of making a broad range of sounds using nasal airsacs located just below the blowhole. Roughly three categories of sounds can be identified: frequency modulated whistles, burst-pulsed sounds and clicks. Dolphins communicate with whistle-like sounds produced by vibrating connective tissue, similar to the way human vocal cords function,[84] and through burst-pulsed sounds, though the nature and extent of that ability is not known. The clicks are directional and are for echolocation, often occurring in a short series called a click train. The click rate increases when approaching an object of interest. Dolphin echolocation clicks are amongst the loudest sounds made by marine animals.[85]

Bottlenose dolphins have been found to have signature whistles, a whistle that is unique to a specific individual. These whistles are used in order for dolphins to communicate with one another by identifying an individual. It can be seen as the dolphin equivalent of a name for humans.[86] These signature whistles are developed during a dolphin's first year; it continues to maintain the same sound throughout its lifetime.[87] In order to obtain each individual whistle sound, dolphins undergo vocal production learning. This consists of an experience with other dolphins that modifies the signal structure of an existing whistle sound. An auditory experience influences the whistle development of each dolphin. Dolphins are able to communicate to one another by addressing another dolphin through mimicking their whistle. The signature whistle of a male bottlenose dolphin tends to be similar to that of their mother, while the signature whistle of a female bottlenose dolphin tends to be more unique.[88] Bottlenose dolphins have a strong memory when it comes to these signature whistles, as they are able to relate to a signature whistle of an individual they have not encountered for over twenty years.[89] Research done on signature whistle usage by other dolphin species is relatively limited. The research on other species done so far has yielded varied outcomes and inconclusive results.[90][91][92][93]

Because dolphins are generally associated in groups, communication is necessary. Signal masking is when other similar sounds (conspecific sounds) interfere with the original acoustic sound.[94] In larger groups, individual whistle sounds are less prominent. Dolphins tend to travel in pods, upon which there are groups of dolphins that range from a few to many. Although they are traveling in these pods, the dolphins do not necessarily swim right next to each other. Rather, they swim within the same general vicinity. In order to prevent losing one of their pod members, there are higher whistle rates. Because their group members were spread out, this was done in order to continue traveling together.

Jumping and playing

Dolphins frequently leap above the water surface, this being done for various reasons. When travelling, jumping can save the dolphin energy as there is less friction while in the air.[95] This type of travel is known as porpoising.[95] Other reasons include orientation, social displays, fighting, non-verbal communication, entertainment and attempting to dislodge parasites.[96][97]

Dolphins show various types of playful behavior, often including objects, self-made bubble rings, other dolphins or other animals.[6][98][99] When playing with objects or small animals, common behavior includes carrying the object or animal along using various parts of the body, passing it along to other members of the group or taking it from another member, or throwing it out of the water.[98] Dolphins have also been observed harassing animals in other ways, for example by dragging birds underwater without showing any intent to eat them.[98] Playful behaviour that involves an other animal species with active participation of the other animal can also be observed however. Playful human interaction with dolphins being the most obvious example, however playful interactions have been observed in the wild with a number of other species as well, such as Humpback Whales and dogs.[100][101]

Intelligence

Dolphins are known to teach, learn, cooperate, scheme, and grieve.[102] The neocortex of many species is home to elongated spindle neurons that, prior to 2007, were known only in hominids.[103] In humans, these cells are involved in social conduct, emotions, judgment, and theory of mind.[104] Cetacean spindle neurons are found in areas of the brain that are homologous to where they are found in humans, suggesting that they perform a similar function.[105]

Brain size was previously considered a major indicator of the intelligence of an animal. Since most of the brain is used for maintaining bodily functions, greater ratios of brain to body mass may increase the amount of brain mass available for more complex cognitive tasks. Allometric analysis indicates that mammalian brain size scales at approximately the ⅔ or ¾ exponent of the body mass.[106] Comparison of a particular animal's brain size with the expected brain size based on such allometric analysis provides an encephalization quotient that can be used as another indication of animal intelligence. Killer whales have the second largest brain mass of any animal on earth, next to the sperm whale.[107] The brain to body mass ratio in some is second only to humans.[108]

Self-awareness is seen, by some, to be a sign of highly developed, abstract thinking. Self-awareness, though not well-defined scientifically, is believed to be the precursor to more advanced processes like meta-cognitive reasoning (thinking about thinking) that are typical of humans. Research in this field has suggested that cetaceans, among others, possess self-awareness.[109] The most widely used test for self-awareness in animals is the mirror test in which a temporary dye is placed on an animal's body, and the animal is then presented with a mirror; they then see if the animal shows signs of self-recognition.[110]

Some disagree with these findings, arguing that the results of these tests are open to human interpretation and susceptible to the Clever Hans effect. This test is much less definitive than when used for primates, because primates can touch the mark or the mirror, while cetaceans cannot, making their alleged self-recognition behavior less certain. Skeptics argue that behaviors that are said to identify self-awareness resemble existing social behaviors, and so researchers could be misinterpreting self-awareness for social responses to another individual. The researchers counter-argue that the behaviors shown are evidence of self-awareness, as they are very different from normal responses to another individual. Whereas apes can merely touch the mark on themselves with their fingers, cetaceans show less definitive behavior of self-awareness; they can only twist and turn themselves to observe the mark.[110]

In 1995, Marten and Psarakos used television to test dolphin self-awareness.[111] They showed dolphins real-time footage of themselves, recorded footage, and another dolphin. They concluded that their evidence suggested self-awareness rather than social behavior. While this particular study has not been repeated since then, dolphins have since passed the mirror test.[110]

Sleeping

Generally, dolphins sleep with only one brain hemisphere in slow-wave sleep at a time, thus maintaining enough consciousness to breathe and to watch for possible predators and other threats. Earlier sleep stages can occur simultaneously in both hemispheres.[112][113][114] In captivity, dolphins seemingly enter a fully asleep state where both eyes are closed and there is no response to mild external stimuli. In this case, respiration is automatic; a tail kick reflex keeps the blowhole above the water if necessary. Anesthetized dolphins initially show a tail kick reflex.[115] Though a similar state has been observed with wild sperm whales, it is not known if dolphins in the wild reach this state.[116] The Indus river dolphin has a sleep method that is different from that of other dolphin species. Living in water with strong currents and potentially dangerous floating debris, it must swim continuously to avoid injury. As a result, this species sleeps in very short bursts which last between 4 and 60 seconds.[117]

Threats

Natural threats

Except for humans (discussed below), dolphins have few natural enemies. Some species or specific populations have none, making them apex predators. For most of the smaller species of dolphins, only a few of the larger sharks, such as the bull shark, dusky shark, tiger shark and great white shark, are a potential risk, especially for calves.[118] Some of the larger dolphin species, especially orcas (killer whales), may also prey on smaller dolphins, but this seems rare.[119][120] Dolphins also suffer from a wide variety of diseases and parasites.[121][122] The Cetacean morbillivirus in particular has been known to cause regional epizootics often leaving hundreds of animals of various species dead.[123][124] Symptoms of infection are often a severe combination of pneumonia, encephalitis and damage to the immune system, which greatly impair the cetacean's ability to swim and stay afloat unassisted.[125][126] A study at the U.S. National Marine Mammal Foundation revealed that dolphins, like humans, develop a natural form of type 2 diabetes which may lead to a better understanding of the disease and new treatments for both humans and dolphins.[127]

Dolphins can tolerate and recover from extreme injuries such as shark bites although the exact methods used to achieve this are not known. The healing process is rapid and even very deep wounds do not cause dolphins to hemorrhage to death. Furthermore, even gaping wounds restore in such a way that the animal's body shape is restored, and infection of such large wounds seems rare.[128]

Human threats

Some dolphin species face an uncertain future, especially some river dolphin species such as the Amazon river dolphin, and the Ganges and Yangtze river dolphin, which are critically or seriously endangered. A 2006 survey found no individuals of the Yangtze river dolphin, which now appears to be functionally extinct.[129]

Pesticides, heavy metals, plastics, and other industrial and agricultural pollutants that do not disintegrate rapidly in the environment concentrate in predators such as dolphins.[130] Injuries or deaths due to collisions with boats, especially their propellers, are also common.

Various fishing methods, most notably purse seine fishing for tuna and the use of drift and gill nets, unintentionally kill many dolphins.[131] Accidental by-catch in gill nets and incidental captures in antipredator nets that protect marine fish farms are common and pose a risk for mainly local dolphin populations.[132][133] In some parts of the world, such as Taiji in Japan and the Faroe Islands, dolphins are traditionally considered food and are killed in harpoon or drive hunts.[134] Dolphin meat is high in mercury and may thus pose a health danger to humans when consumed.[135]

Dolphin safe labels attempt to reassure consumers that fish and other marine products have been caught in a dolphin-friendly way. The earliest campaigns with "Dolphin safe" labels were initiated in the 1980s as a result of cooperation between marine activists and the major tuna companies, and involved decreasing incidental dolphin kills by up to 50% by changing the type of nets used to catch tuna. The dolphins are netted only while fishermen are in pursuit of smaller tuna. Albacore are not netted this way, making albacore the only truly dolphin-safe tuna.[136] Loud underwater noises, such as those resulting from naval sonar use, live firing exercises, and certain offshore construction projects such as wind farms, may be harmful to dolphins, increasing stress, damaging hearing, and causing decompression sickness by forcing them to surface too quickly to escape the noise.[137][138]

Dolphins and other smaller cetaceans are also hunted in an activity known as dolphin drive hunting. This is accomplished by driving a pod together with boats and usually into a bay or onto a beach. Their escape is prevented by closing off the route to the ocean with other boats or nets. Dolphins are hunted this way in several places around the world, including the Solomon Islands, the Faroe Islands, Peru, and Japan, the most well-known practitioner of this method. By numbers, dolphins are mostly hunted for their meat, though some end up in dolphinariums. Despite the controversial nature of the hunt resulting in international criticism, and the possible health risk that the often polluted meat causes, thousands of dolphins are caught in drive hunts each year.

Relationships with humans

In history and religion

Dolphins have long played a role in human culture. Dolphins are sometimes used as symbols, for instance in heraldry. When heraldry developed in the Middle Ages, not much was known about the biology of the dolphin and it was often depicted as a sort of fish. Traditionally, the stylised dolphins in heraldry still may take after this notion, sometimes showing the dolphin skin covered with fish scales.

Dolphins are present in the coat of arms of Anguilla and the coat of arms of Romania,[139] and the coat of arms of Barbados has a dolphin supporter.[140] A well-known historical example of a dolphin in heraldry, was the arms for the former province of the Dauphiné in southern France, from which were derived the arms and the title of the Dauphin of France, the heir to the former throne of France (the title literally means "The Dolphin of France").

"Dolfin" was the name of an aristocratic family in the maritime Republic of Venice, whose most prominent member was the 13th Century Doge Giovanni Dolfin.

In Greek myths, they were seen invariably as helpers of humankind. Dolphins also seem to have been important to the Minoans, judging by artistic evidence from the ruined palace at Knossos. Dolphins are common in Greek mythology, and many coins from ancient Greece have been found which feature a man, a boy or a deity riding on the back of a dolphin.[141] The Ancient Greeks welcomed dolphins; spotting dolphins riding in a ship's wake was considered a good omen.[142] In both ancient and later art, Cupid is often shown riding a dolphin. A dolphin rescued the poet Arion from drowning and carried him safe to land, at Cape Matapan, a promontory forming the southernmost point of the Peloponnesus. There was a temple to Poseidon and a statue of Arion riding the dolphin.[143]

The Greeks reimagined the Phoenician god Melqart as Melikertês (Melicertes) and made him the son of Athamas and Ino. He drowned but was transfigured as the marine deity Palaemon, while his mother became Leucothea. (cf Ino.) At Corinth, he was so closely connected with the cult of Poseidon that the Isthmian Games, originally instituted in Poseidon's honor, came to be looked upon as the funeral games of Melicertes. Phalanthus was another legendary character brought safely to shore (in Italy) on the back of a dolphin, according to Pausanias.

Dionysus was once captured by Etruscan pirates who mistook him for a wealthy prince they could ransom. After the ship set sail Dionysus invoked his divine powers, causing vines to overgrow the ship where the mast and sails had been. He turned the oars into serpents, so terrifying the sailors that they jumped overboard, but Dionysus took pity on them and transformed them into dolphins so that they would spend their lives providing help for those in need. Dolphins were also the messengers of Poseidon and sometimes did errands for him as well. Dolphins were sacred to both Aphrodite and Apollo.

In Hindu mythology the Ganges River Dolphin is associated with Ganga, the deity of the Ganges river. The dolphin is said to be among the creatures which heralded the goddess' descent from the heavens and her mount, the Makara, is sometimes depicted as a dolphin.[144]

The Boto, a species of river dolphin that resides in the Amazon River, are believed to be shapeshifters, or encantados, who are capable of having children with human women.

In captivity

Species

The renewed popularity of dolphins in the 1960s resulted in the appearance of many dolphinaria around the world, making dolphins accessible to the public. Criticism and animal welfare laws forced many to close, although hundreds still exist around the world. In the United States, the best known are the SeaWorld marine mammal parks. In the Middle East the best known are Dolphin Bay at Atlantis, The Palm and the Dubai Dolphinarium.

.jpg)

Various species of dolphins are kept in captivity. These small cetaceans are more often than not kept in theme parks, such as SeaWorld, commonly known as a dolphinarium. Bottlenose Dolphins are the most common species of dolphin kept in dolphinariums as they are relatively easy to train, have a long lifespan in captivity and have a friendly appearance. Hundreds if not thousands of Bottlenose Dolphins live in captivity across the world, though exact numbers are hard to determine. Other species kept in captivity are Spotted Dolphins, False Killer Whales and Common Dolphins, Commerson's Dolphins, as well as Rough-toothed Dolphins, but all in much lower numbers than the Bottlenose Dolphin. There are also fewer than ten Pilot Whales, Amazon River Dolphins, Risso's Dolphins, Spinner Dolphins, or Tucuxi in captivity.[145] An unusual and very rare hybrid dolphin, known as a Wolphin, is kept at the Sea Life Park in Hawaii, which is a cross between a Bottlenose Dolphin and a False Killer Whale.[146]

Killer whales are well known for their performances in shows, but the number of Orcas kept in captivity is very small, especially when compared to the number of bottlenose dolphins, with only 44 captive killer whales being held in aquaria as of 2012.[147] The killer whale's intelligence, trainability, striking appearance, playfulness in captivity and sheer size have made it a popular exhibit at aquaria and aquatic theme parks. From 1976 to 1997, 55 whales were taken from the wild in Iceland, 19 from Japan, and three from Argentina. These figures exclude animals that died during capture. Live captures fell dramatically in the 1990s, and by 1999, about 40% of the 48 animals on display in the world were captive-born.[148]

Organizations such as the Mote Marine Laboratory rescue and rehabilitate sick, wounded, stranded or orphaned dolphins while others, such as the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society and Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society, work on dolphin conservation and welfare. India has declared the dolphin as its national aquatic animal in an attempt to protect the endangered Ganges River Dolphin. The Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary has been created in the Ganges river for the protection of the animals.[149]

Controversy

Organizations such as World Animal Protection and the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society campaign against the practice of keeping them in captivity. In captivity, they often develop pathologies, such as the dorsal fin collapse seen in 60–90% of male killer whales. Captives have vastly reduced life expectancies, on average only living into their 20s, although there are examples of killer whales living longer, including several over 30 years old, and two captive orcas, Corky II and Lolita, are in their mid-40s. In the wild, females who survive infancy live 46 years on average, and up to 70–80 years in rare cases. Wild males who survive infancy live 31 years on average, and up to 50–60 years.[150] Captivity usually bears little resemblance to wild habitat, and captive whales' social groups are foreign to those found in the wild. Critics claim captive life is stressful due to these factors and the requirement to perform circus tricks that are not part of wild killer whale behavior. Wild killer whales may travel up to 160 kilometres (100 mi) in a day, and critics say the animals are too big and intelligent to be suitable for captivity.[151] Captives occasionally act aggressively towards themselves, their tankmates, or humans, which critics say is a result of stress.[152] Between 1991 and 2010, the bull orca known as Tilikum was involved in the death of three people, and was featured in the critically acclaimed 2013 film, Blackfish.[153] Tilikum has lived at SeaWorld since 1992.[154][155][156]

Although dolphins generally interact well with humans, some attacks have occurred, most of them resulting in small injuries.[157] Orcas, the largest species of dolphin, have been involved in fatal attacks on humans in captivity. The record-holder of documented orca fatal attacks, a male named Tilikum that belongs to SeaWorld, has played a role in the death of three people in three different incidents (1991, 1999 and 2010).[158] Tilikum's behaviour sparked the production of the documentary Blackfish, which focuses on the consequences of keeping orcas in captivity. There are documented incidents in the wild, too, but none of them fatal.[159]

Fatal attacks from other species are less common, but there is a registered occurrence off the coast of Brazil in 1994, when a man died after being attacked by a bottlenose dolphin named Tião.[160][161] Tião had suffered harassment by human visitors, including attempts to stick ice cream sticks down her blowhole.[162] Non-fatal incidents occur more frequently, both in the wild and in captivity.

While dolphin attacks occur far less frequently than attacks by other sea animals, such as sharks, some scientists are worried about the careless programs of human-dolphin interaction. Dr. Andrew J. Read, a biologist at the Duke University Marine Laboratory who studies dolphin attacks, points out that dolphins are large and wild predators, so people should be more careful when they interact with them.[157]

Several scientists who have researched dolphin behaviour have proposed that dolphins' unusually high intelligence in comparison to other animals means that dolphins should be seen as non-human persons who should have their own specific rights and that it is morally unacceptable to keep them captive for entertainment purposes or to kill them either intentionally for consumption or unintentionally as by-catch.[163] [164] Four countries – Chile, Costa Rica, Hungary, and India – have declared dolphins to be "non-human persons" and have banned the capture and import of live dolphins for entertainment.[165][166]

Military

A military dolphin is a dolphin trained for military uses. A number of militaries have employed dolphins for various purposes from finding mines to rescuing lost or trapped humans. The military use of dolphins, however, drew scrutiny during the Vietnam War when rumors circulated that the United States Navy was training dolphins to kill Vietnamese divers.[167] The United States Navy denies that at any point dolphins were trained for combat. Dolphins are still being trained by the United States Navy for other tasks as part of the U.S. Navy Marine Mammal Program. The Russian military is believed to have closed its marine mammal program in the early 1990s. In 2000 the press reported that dolphins trained to kill by the Soviet Navy had been sold to Iran.[168]

Therapy

Dolphins are an increasingly popular choice of animal-assisted therapy for psychological problems and developmental disabilities. For example, a 2005 study found dolphins an effective treatment for mild to moderate depression.[169] However, this study was criticized on several grounds. For example, it is not known whether dolphins are more effective than common pets.[170] Reviews of this and other published dolphin-assisted therapy (DAT) studies have found important methodological flaws and have concluded that there is no compelling scientific evidence that DAT is a legitimate therapy or that it affords more than fleeting mood improvement.[171]

Consumption

Cuisine

In some parts of the world, such as Taiji, Japan and the Faroe Islands, dolphins are traditionally considered as food, and are killed in harpoon or drive hunts.[172] Dolphin meat is consumed in a small number of countries world-wide, which include Japan[173] and Peru (where it is referred to as chancho marino, or "sea pork").[174] While Japan may be the best-known and most controversial example, only a very small minority of the population has ever sampled it.

Dolphin meat is dense and such a dark shade of red as to appear black. Fat is located in a layer of blubber between the meat and the skin. When dolphin meat is eaten in Japan, it is often cut into thin strips and eaten raw as sashimi, garnished with onion and either horseradish or grated garlic, much as with sashimi of whale or horse meat (basashi). When cooked, dolphin meat is cut into bite-size cubes and then batter-fried or simmered in a miso sauce with vegetables. Cooked dolphin meat has a flavor very similar to beef liver.[175]

Health concerns

The Faroe Islands population was exposed to methylmercury largely from contaminated pilot whale meat, which contained very high levels of about 2 mg methylmercury/kg. However, the Faroe Islands populations also eat significant amounts of fish. The study of about 900 Faroese children showed that prenatal exposure to methylmercury resulted in neuropsychological deficits at 7 years of age

There have been human health concerns associated with the consumption of dolphin meat in Japan after tests showed that dolphin meat contained high levels of mercury.[176] There are no known cases of mercury poisoning as a result of consuming dolphin meat, though the government continues to monitor people in areas where dolphin meat consumption is high. The Japanese government recommends that children and pregnant women avoid eating dolphin meat on a regular basis.[177]

Similar concerns exist with the consumption of dolphin meat in the Faroe Islands, where prenatal exposure to methylmercury and PCBs primarily from the consumption of pilot whale meat has resulted in neuropsychological deficits amongst children.[176]

References

- 1 2 3 Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "δελφίς". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ↑ Dolphin. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth ed.) (Dictionary.com). Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ↑ delphinus, Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ "mereswine - definition and meaning of mereswine at Wordnik.com". www.wordnik.com. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Aquatic Life of the World. Marshall Cavendish. 1 November 2000. p. 652. ISBN 978-0-7614-7170-7. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- 1 2 Walker, Sally M. (November 2007). Dolphins. Lerner Publications. pp. 6, 30. ISBN 978-0-8225-6767-7.

- ↑ Andrew J. Read (1999). Porpoises. Voyageur Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-89658-420-4. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ "Coryphaena hippurus". FishBase. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Stephen Leatherwood (1988). Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises of the Eastern North Pacific and Adjacent Arctic Waters: A Guide to Their Identification. Courier Dover Publications. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-486-25651-1. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Ron Hirschi (April 2002). Dolphins. Marshall Cavendish. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7614-1443-8. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- 1 2 Stephanie Nowacek; Douglas Nowacek (2006). Discovering Dolphins. Voyageur Press. pp. 5, 9. ISBN 978-0-7603-2561-2. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Leatherwood, S.; Prematunga, W.P.; Girton, P.; McBrearty, D.; Ilangakoon, A.; McDonald, D (1991). Records of 'blackfish' (killer, false killer, pilot, pygmy killer, and melon-headed whales) in the Indian Ocean Sanctuary, 1772-1986 in Cetaceans and cetacean research in the Indian Ocean Sanctuary. UNEP Marine Mammal Technical Report. pp. 33–65. ASIN B00KX9I8Y8.

- ↑ "Style guide, animal names". Dictionary.com. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ↑ "New Dolphin Species Discovered in Australia". September 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Dolphin Safari sightings log". 2006. Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ↑ Texas Tech University (1997). "Mammals of Texas – Rough-toothed Dolphin". Retrieved December 8, 2006.

- ↑ Robin's Island. "Dolphins at SeaWorld California". Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ↑ Denise L. Herzing, Kelly Moewe and Barbara J. Brunnick (2003). "Interspecies interactions between Atlantic spotted dolphins, Stenella frontalis and bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus, on Great Bahama Bank, Bahamas" (PDF). Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ↑ Lee, Jeanette J. (April 15, 2005). "Whale-Dolphin Hybrid Has Baby 'Wholphin'". Livescience.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 17, 2005. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ↑ Northeastern Ohio Universities Colleges of Medicine and Pharmacy. "Whales Descended From Tiny Deer-like Ancestors". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (2004). The Ancestor's Tale, A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-00583-8.

- ↑ Thewissen, J. G. M.; Williams, E. M. (1 November 2002). "THE EARLY RADIATIONS OF CETACEA (MAMMALIA): Evolutionary Pattern and Developmental Correlations". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 33 (1): 73–90. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.020602.095426.

- ↑ "Introduction to Cetacea: Archaeocetes: The Oldest Whales". University of Berkeley. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ↑ Thewissen, J. G. M.; Cooper, L. N.; Clementz, M. T.; Bajpai, S.; Tiwari, B. N. (2007). "Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the Eocene epoch of India" (PDF). Nature 450 (7173): 1190–1194. Bibcode:2007Natur.450.1190T. doi:10.1038/nature06343. PMID 18097400.

- ↑ Fahlke, Julia M.; Gingerich, Philip D.; Welsh, Robert C.; Wood, Aaron R. (2011). "Cranial asymmetry in Eocene archaeocete whales and the evolution of directional hearing in water". PNAS 108 (35): 14545–14548. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10814545F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1108927108. PMID 21873217.

- ↑ "More DNA Support for a Cetacea/Hippopotamidae Clade: The Blood-Clotting Protein Gene y-Fibrinogen". BBC News. 8 May 2002. Retrieved 20 August 2006.

- ↑ "New Dawn". Walking with Prehistoric Beasts. 2002. Discovery Channel.

- ↑ Rose, Kenneth D. (2001). "The Ancestry of Whales" (PDF) 239. University of Washington: 2216–2217.

- ↑ Bebej, R. M.; ul-Haq, M.; Zalmout, I. S.; Gingerich, P. D. (June 2012). "Morphology and Function of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus domandaensis (Mammalia, cetacea) from the Middle Eocene Domanda Formation of Pakistan". Journal of Mammalian Evolution 19 (2): 77–104. doi:10.1007/S10914-011-9184-8.

- ↑ Lovett, Richard A. (8 November 2006). "Dolphin With Four Fins May Prove Terrestrial Origins". National Geographic. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ Gatesy, John (3 February 1997). "whales' closest relative" (PDF). University of Arizona. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ "The evolution of whales". University of Berkeley. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Boisserie, Jean-Renaud; Lihoreau, Fabrice; Brunet, Michel (2005). "The position of Hippopotamidae within Cetartiodactyla". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102 (5): 1537–1541. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.1537B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409518102. PMC 547867. PMID 15677331. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Katherine Ralls; Sarah Mesnick. Sexual Dimorphism (PDF). pp. 1005–1011. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Cetacean Curriculum – A teacher's guide to introducing and using whales, dolphins, & porpoises in the classroom" (PDF). American Cetacean Society. 28 November 2004. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

Sound production in cetaceans is a complex phenomenon not fully understood by scientists.

- ↑ Scholander, Per Fredrik (1940). "Experimental investigations on the respiratory function in diving mammals and birds". Hvalraadets Skrifter (Oslo: Norske Videnskaps-Akademi) 22.

- 1 2 Klinowska, Margaret; Cooke, Justin (1991). Dolphins, Porpoises, and Whales of the World: the IUCN Red Data Book (PDF). Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Stevens, C. Edward; Hume, Ian D. (1995). Comparative Physiology of the Vertebrate Digestive System. Cambridge University Press. p. 317.

- ↑ "Beluga Whale: The White Melon-headed Creature Of The Cold". Yellowmagpie.com. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "About Whales". Whalesalive.org.au. 26 June 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "Boto (Amazon river dolphin) Inia geoffrensis". American Cetacean Society. 2002. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ↑ Cozzi, Bruno Cozzi; Mazzario, Sandro; Podestà, Michela; Zotti, Alessandro (2009). "Diving Adaptations of the Cetacean Skeleton" (PDF). Open Zoology Journal 2: 24–32. doi:10.2174/1874336600902010024.

- ↑ Norena, S. R.; Williams, T. M. (2000). "Body size and skeletal muscle myoglobin of cetaceans: adaptations for maximizing dive duration". Science Direct 126 (2): 181–191. doi:10.1016/s1095-6433(00)00182-3.

- ↑ Nummela, Sirpa; Thewissen, J.G.M; Bajpai, Sunil; Hussain, Taseer; Kumar, Kishor (2007). "Sound transmission in archaic and modern whales: Anatomical adaptations for underwater hearing". The Anatomical Record 290 (6): 716–733. doi:10.1002/ar.20528. PMID 17516434.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas, Jeanette A.; Kastelein, Ronald A., eds. (2002). Sensory Abilities of Cetaceans: Laboratory and Field Evidence 196. doi:10.1007/978-4899-0858-2. ISBN 978-1-4899-0860-5.

- ↑ Thewissen, J. G. M. (2002). "Hearing". In Perrin, William R.; Wirsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J.G.M. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 570–2. ISBN 0-12-551340-2.

- ↑ Ketten, Darlene R. (1992). "The Marine Mammal Ear: Specializations for Aquatic Audition and Echolocation". In Webster, Douglas B.; Fay, Richard R.; Popper, Arthur N. The Evolutionary Biology of Hearing (PDF). Springer. pp. 725–727. Retrieved March 2013.

- ↑ Jeanette A. Thomas and Ronald A. Kastelein., ed. (1990). A Proposed Echolocation Receptor for the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus): Modelling the Receive Directivity from Tooth and Lower Jaw Geometry NATO ASI Series A: Sensory Abilities of Cetaceans 196. NY: Plenum. pp. 255–267. ISBN 978-0-306-43695-6.

- ↑ Bjorn Mauck, Ulf Eysel and Guide Dehnhardt (2000). "Selective heating of vibrissal follicles in seals (Phoca vitulina) and dolphins (Sotalia fluviatilis guianensis)" (PDF). Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ↑ Harley, Heidi E.; DeLong, Caroline M. (2008). "Echoic Object Recognition by the Bottlenose Dolphin" (PDF). Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews 3: 45–65. doi:10.3819/ccbr.2008.30003.

- ↑ Stepanek, Laurie (May 19, 1998). "Amazon River Dolphin (Inia geoffrensis)". Texas Marine Mammal Stranding Network. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ↑ Mass, Alla M.; Supin, Alexander, Y. A. (21 May 2007). "Adaptive features of aquatic mammals' eyes". Anatomical Record 290 (6): 701–715. doi:10.1002/ar.20529.

- ↑ Davidson College, biology department (2001). "Bottlenose Dolphins – Altruism". Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- ↑ Lilley, Ray (2008-03-12). "Dolphin Saves Stuck Whales, Guides Them Back to Sea". National Geographic. Associated Press. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Dolphins save swimmers from shark". CBC News. 2004-11-24. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ↑ Celizic, Mike (2007-11-08). "Dolphins save surfer from becoming shark's bait". MSNBC. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ↑ Dolphin Mysteries: Unlocking the Secrets of Communication. Yale University Press. 2008. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-300-12112-4. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ Rowan Hooper (2005). "Dolphins teach their children to use sponges". Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ↑ Nic Fleming, Science correspondent for the Telegraph (December 5, 2007). "Dolphins woo females with bunches of weeds". The Daily Telegraph (London). Retrieved February 11, 2008.

- ↑ Lilley R., 2008. Dolphin Saves Stuck Whales, Guides Them Back to Sea. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/03/080312-AP-dolph-whal.html. The Associated Press. National Geographic News. retrieved on 24-05-2014

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/21146455

- ↑ Dr. George Johnson. "Is Flipper A Senseless Killer?". Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ↑ William F. Perrin; Bernd Wursig; J. G.M. Thewissen (26 February 2009). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ↑ Carol J. Howard (1 December 1995). Dolphin Chronicles. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-553-37778-1. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ↑ Bernd G. Würsig; Bernd Wursig, Melany Wursig (2010). The Dusky Dolphin: Master Acrobat Off Different Shores. Academic Press. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-0-12-373723-6. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ↑ Edward F. Gibbons, Jr.; Barbara Susan Durrant; Jack Demarest (1995). Conservation Endangered Spe: An Interdisciplinary Approach. SUNY Press. pp. 435–. ISBN 978-0-7914-1911-3. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 J. Silva Jr, F. Silva & I Sazima (2005) - Rest, nurture, sex, release, and play: diurnal underwater behaviour of the spinner dolphin at Fernando de Noronha Archipelago, SW Atlantic - Mating behaviour, article retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ CMS Sotalia fluviatilis - Reproduction, article retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ Marinebio.org - Orcas (Killer Whales), Orcinus orca - Life History, article retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ Mark Simmonds, Whales and Dolphins of the World, New Holland Publishers (2007), Ch. 1, p. 32 ISBN 1-84537-820-2.

- ↑ W. Perrin & S. Reilly (1984). Reproductive Parameters of Dolphins.

- ↑ Volker Sommer, Paul L. Vasey (2006). "Chapter 4". Homosexual Behaviour in Animals – an Evolutionary perspective.

- ↑ Bruce Bagemihl (1999). Biological Exuberance – Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity.

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tc3NGR55OsUC&lpg=PA97&dq=autocunnilingus&pg=PA98&hl=en#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Scott, Erin; Mann, Janet; Watson-Capps, Jana; Sargeant, Brooke; Connor, Richard (2005). "Aggression in bottlenose dolphins: Evidence for sexual coercion, male-male competition, and female tolerance through analysis of tooth-rake marks and behaviour". Behaviour 142 (1): 21–44. doi:10.1163/1568539053627712.

- ↑ R. Connor, R. Smolker & A. Richards (1992). Two levels of alliance formation among male bottlenose dolphins.

- ↑ Amy Samuels, Lars Bejder, Rochelle Constantine and Sonja Heinrich (2003). "chapter 15 Marine Mammals: Fisheries, Tourism and Management Issues". Cetaceans that are typically lonely and seek human company (PDF). pp. 266–268. Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 Dolphin's diet

- ↑ U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service. "Coastal Stock(s) of Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin: Status Review and Management Proceedings and Recommendations from a Workshop held in Beaufort, North Carolina, 13 September 1993 – 14 September 1993" (PDF). pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Gregory K. Silber, Dagmar Fertl (1995) – Intentional beaching by bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the Colorado River Delta, Mexico.

- ↑ M.B. Santos, R. Fernández, A. López, J.A. Martínez and G.J. Pierce (2007). "Variability in the diet of bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops truncatus, in Galician waters, north-western Spain, 1990–2005". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 87: 231. doi:10.1017/S0025315407055233.

- ↑ "Brazil's sexiest secret". The Daily Telegraph (London). 2006-03-08. Archived from the original on 2008-03-13. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ↑ Dr. Moti Nissani (2007). "Bottlenose Dolphins in Laguna Requesting a Throw Net Supporting material for Dr. Nissani's presentation at the 2007 International Ethological Conference". Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ↑ Viegas, Jennifer (2011). "Dolphins Talk Like Humans". Discovery News. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ↑ Au, W. W. L. (1993). The Sonar of Dolphins. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-97835-0.

- ↑ "Dolphins 'call each other by name'". BBC News. July 22, 2013.

- ↑ Janik, Vincent; Laela Sayigh (7 May 2013). "Communication in bottlenose dolphins: 50 years of signature whistle research". Journal of Comparative Physiology 199 (6): 479–489. doi:10.1007/s00359-013-0817-7.

- ↑ "Marine Mammal vocalizations: language or behavior?". August 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Dolphins keep lifelong social memories, longest in a non-human species". August 24, 2013.

- ↑ Emily T. Griffiths (2009). "Whistle repertoire analysis of the short beaked Common Dolphin, Delphinus delphis, from the Celtic Deep and the Eastern and the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean", Master's Thesis, School of Ocean Sciences Bangor University

- ↑ Melba C. Caldwell Et Al. – Statistical Evidence for Signture Whistles in the Spotted Dolphin, Stenella plagiodon.

- ↑ Melba C. Caldwell Et Al. – Statistical Evidence for Signture Whistles in the Pacific Whitesided Dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obliquidens.

- ↑ Rüdiger Riesch Et Al. – Stability and group specificity of stereotyped whistles in resident killer whales, Orcinus orca, off British Columbia.

- ↑ Quick, Nicola; Vincent Janik (2008). "Whistle Rates of Wild Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus): Influences of Group Size and Behavior". Journal of Comparative Psychology 122 (3): 305–311. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.122.3.305.

- 1 2 Weihs, D. (2002). "Dynamics of Dolphin Porpoising Revisited". Integrative and Comparative Biology 42 (5): 1071–1078. doi:10.1093/icb/42.5.1071.

- ↑ David Lusseau (2006), Why do dolphins jump? Interpreting the behavioural repertoire of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) in Doubtful Sound, New Zealand

- ↑ Corey Binns – LiveScience (2006), How Dolphins Spin, and Why, article retrieved 8 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 Robin D. Paulos (2010), Play in Wild and Captive Cetaceans

- ↑ Brenda McCowan; Lori Marino; Erik Vance; Leah Walke; Diana Reiss (2000). "Bubble Ring Play of Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus):Implications for Cognition" (PDF). Journal of Comparative Psychology l14 (1): 98–106. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.114.1.98.

- ↑ Mark H. Deakos et al. (2010), Two Unusual Interactions Between a Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and a Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Hawaiian Waters.

- ↑ Cathy Hayes for Irish Central (2011), Amazing footage of a dog playing with a dolphin off the coast of Ireland, article retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ↑ Siebert, Charles (8 July 2009). "Watching Whales Watching Us". New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Watson, K.K.; Jones, T. K.; Allman, J. M. (2006). "Dendritic architecture of the Von Economo neurons". Neuroscience 141 (3): 1107–1112. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.084. PMID 16797136.

- ↑ Allman, John M.; Watson, Karli K.; Tetreault, Nicole A.; Hakeem, Atiya Y. (2005). "Intuition and autism: a possible role for Von Economo neurons". Trends Cogn Sci 9 (8): 367–373. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.06.008. PMID 16002323.

- ↑ Hof, Patrick R.; Van Der Gucht, Estel (2007). "Structure of the cerebral cortex of the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae (Cetacea, Mysticeti, Balaenopteridae)". The Anatomical Record 290 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1002/ar.20407. PMID 17441195.

- ↑ Moore, Jim. "Allometry". University of California San Diego. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ↑ "How smart are they?". Orlando Sentinel. March 7, 2010.

- ↑ Fields, R. Douglas. "Are whales smarter than we are?". Scientific American. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ↑ "Elephant Self-Awareness Mirrors Humans". Live Science. 30 October 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 Derr, Mark. "Mirror test". New York Times. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ↑ Marten, Ken; Psarakos, Suchi (June 1995). "Using Self-View Television to Distinguish between Self-Examination and Social Behavior in the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)". Consciousness and Cognition 4 (2): 205–224. doi:10.1006/ccog.1995.1026.

- ↑ Mukhametov, L. M.; Supin, A. Ya. (1978). "Sleep and vigil in dolphins". Marine mammals. Moscow: Nauka.

- ↑ Mukhametov, Lev (1984). "Sleep in marine mammals". Experimental Brain Research. Experimental Brain Research Supplementum. 8 (suppl.): 227–238. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-69554-4_17. ISBN 978-3-642-69556-8.

- ↑ Dallas Grasby (1994). "Excerpts from "Sleep in marine mammals", L.M. Mukhametov". Experimental Brain Research. 8 (suppl.). Retrieved February 11, 2008.

- ↑ McCormick, James G. (2007). "Behavioral Observations of Sleep and Anesthesia in the Dolphin: Implications for Bispectral Index Monitoring of Unihemispheric Effects in Dolphins". Anesthesia & Analgesia 104 (1): 239–241. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000250369.33700.eb.

- ↑ BBC (2008-02-20). "Sperm whales caught 'cat napping'". BBC News. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ↑ Martin, G. Neil; Carlson, Neil R.; Buskist, William (1997). Psychology, third edition. Pearson Allyn & Bacon. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-273-71086-8.

- ↑ Michael R. Heithaus (1999), Predator-prey and competitive interactions between sharks (order Selachii) and dolphins (suborder Odontoceti): a review

- ↑ Emine Sinmaz for the Daily Mail (2013), Eight-ton orca leaps 15ft into the air to finally capture dolphin he wanted for dinner after two-hour chase, article retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ↑ Nadia Drake for WIRED (2013), Photographer Captures Stunning Killer Whale Attack on Dolphin, article retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ↑ Bossart, G. D. (2007). "Emerging diseases in marine mammals: from dolphins to manatees" (PDF). Microbe 2 (11): 544–549.

- ↑ Woodard, J. C.; Zam, S. G.; Caldwell, D. K.; Caldwell, M. C. (1969). "Some Parasitic Diseases of Dolphins" (PDF). Veterinary Pathology 6 (3): 257–272. doi:10.1177/030098586900600307.

- ↑ Bellière, E. N.; Esperón, F.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J. M. (2011). "Genetic comparison among dolphin morbillivirus in the 1990–1992 and 2006–2008 Mediterranean outbreaks". Infection, Genetics and Evolution 11 (8): 1913–1920. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2011.08.018. PMID 21888991.

- ↑ Jane J. Lee for National Geographic (2013), What's Killing Bottlenose Dolphins? Experts Discover Cause., article retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ Guardo, G. D.; Marruchella, G.; Agrimi, U.; Kennedy, S. (2005). "Morbillivirus Infections in Aquatic Mammals: A Brief Overview". Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series A 52 (2): 88–93. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0442.2005.00693.x. PMID 15737178.

- ↑ Stone, B. M.; Blyde, D. J.; Saliki, J. T.; Blas-Machado, U.; Bingham, J.; Hyatt, A.; Wang, J.; Payne, J.; Crameri, S. (2011). "Fatal cetacean morbillivirus infection in an Australian offshore bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)". Australian Veterinary Journal 89 (11): 452–457. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00849.x. PMID 22008125.

- ↑ US National Marine Mammal Foundation (2010-02-18). "Scientists Find Clues in Dolphins to Treat Diabetes in Humans". Archived from the original on 2010-04-11. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ↑ Georgetown University Medical Center. "Dolphins' "Remarkable" Recovery from Injury Offers Important Insights for Human Healing". Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ↑ Douglas Williams for Shanghai Daily (December 4, 2006). "Yangtze dolphin may be extinct". Archived from the original on 2006-12-24. Retrieved December 9, 2006.

- ↑ "TED: Stephen Palumbi: Following the mercury trail". Youtube.com. June 30, 2010. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ Clover, Charles. (2004). The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. Ebury Press, London. ISBN 978-0-09-189780-2.

- ↑ Díaz López, Bruno; Bernal Shirai, J.A. (2006). "Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) presence and incidental capture in a marine fish farm on the north-eastern coast of Sardinia (Italy)". Journal of Marine Biological Association UK 87: 113–117. doi:10.1017/S0025315407054215.

- ↑ Díaz López, Bruno (2006). "Interactions between Mediterranean bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and gillnets off Sardinia, Italy". ICES Journal of Marine Science 63 (5): 946–951. doi:10.1016/j.icesjms.2005.06.012.

- ↑ Matsutani, Minoru (2009-09-23). "Details on how Japan's dolphin catches work". Japan Times. p. 3.

- ↑ Johnston, Eric (2009-09-23). "Mercury danger in dolphin meat". Japan Times. p. 3.

- ↑ "Time Of Truth For US Dolphin Safe Logos". atuna. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ CBC news (2003-10-09). "Navy sonar may be killing whales, dolphins". CBC News. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ↑ "Npower renewables Underwater noise & vibration, section 9.4" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-22. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ↑ Hentea, Călin (2007). Brief Romanian Military History. Maryland, USA: Scarecrow Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8108-5820-6.

- ↑ Ali, Arif (1996). Barbados: Just Beyond Your Imagination. Hertford, UK: Hansib Publications. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-870518-54-3.

- ↑ "Taras". Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ↑ Eyers, Jonathan (2011). Don't Shoot the Albatross!: Nautical Myths and Superstitions. A&C Black, London, UK. ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2.

- ↑ Herodotus I.23; Thucydides I.128, 133; Pausanias iii.25, 4

- ↑ Vijay Singh (1994). The River Goddess. London. ISBN 978-1-85103-195-5.

- ↑ Rose, Naoimi; Parsons, E.C.M.; Farinato, Richard. The Case Against Marine Mammals in Captivity (PDF) (4 ed.). Humane Society of the United States. pp. 13, 42, 43, 59.

- ↑ Sean B. Carroll. "Remarkable creatures". Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ↑ "Orcas in Captivity - A look at killer whales in aquariums and parks]". 23 November 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ NMFS 2005, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ india.gov. "National Aquatic Animal". india.gov.

- ↑ Rose, N. A. (2011). "Killer Controversy: Why Orcas Should No Longer Be Kept in Captivity" (PDF). Humane Society International and the Humane Society of the United States. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Whale Attack Renews Captive Animal Debate". CBS News. March 1, 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ Susan Jean Armstrong. Animal Ethics Reader. ISBN 978-0-415-27589-7.

- ↑ "Blackfish". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Tim (2011). "The Killer in the Pool". The Best American Sampler 2011. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 336.

- ↑ "Corpse Is Found on Whale". New York Times. July 7, 1999. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ↑ "SeaWorld trainer killed by killer whale". CNN. February 25, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- 1 2 William Broad (1999-07-06). "An article on the aggressive nature of dolphins". Fishingnj.org. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ Pilkington, Ed (2010-02-25). "Killer whale Tilikum to be spared after drowning trainer by ponytail". The Guardian (London).

- ↑ "Killer whale bumps but doesn't bite boy". Juneau Empire – Alaska's Capital City Online Newspaper. 2005-08-19. Archived from the original on 2010-04-11. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ Wong, David. "The 6 Cutest Animals That Can Still Destroy You". Cracked.com. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ "Male Dolphin Kills Man". Science-frontiers.com. Sep–Oct 1995. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ "LONE DOLPHINS – FRIEND OR FOE?". BBC. 2002-09-09. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ Thomas I. White (2007). In defense of dolphins: the new moral frontier. Blackwell Public Philosophy Series. ISBN 978-1-4051-5778-0.

- ↑ Jonathan Leake and Helen Brooks for The Sunday Times (2010), Scientists say dolphins should be treated as 'non-human persons', article retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Land, Graham (29 July 2013). Dolphin rights: The world should follow India's lead. Asiancorrespondent.com. Hybrid News Ltd. Accessed on 29 July 2013.

- ↑ Policy on establishment of dolphinarium

- ↑ PBS – Frontline. "The Story of Navy dolphins". Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Iran buys kamikaze dolphins". BBC News. 2000-03-08. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ↑ Antonioli, C; Reveley, MA (2005). "Randomised controlled trial of animal facilitated therapy with dolphins in the treatment of depression". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 331 (7527): 1231. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7527.1231. JSTOR 25455488. PMC 1289317. PMID 16308382.

- ↑ Biju Basil, Maju Mathews (2005). "Methodological concerns about animal-facilitated therapy with dolphins". BMJ 331 (7529): 1407. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7529.1407. PMC 1309662. PMID 16339258.

- ↑ Lori Marino, Scott O. Lilienfeld (2007). "Dolphin-Assisted Therapy: more flawed data and more flawed conclusions" (PDF). Anthrozoos 20 (3): 239–49. doi:10.2752/089279307X224782. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- ↑ Matsutani, Minoru (September 23, 2009). "Details on how Japan's dolphin catches work". Japan Times. p. 3.

- ↑ McCurry, Justin (2009-09-14). "Dolphin slaughter turns sea red as Japan hunting season returns". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Hall, Kevin G. (2003). "Dolphin meat widely available in Peruvian stores: Despite protected status, 'sea pork' is popular fare". The Seattle Times.

- ↑ イルカの味噌根菜煮 [Dolphin in Miso Vegetable Stew]. Cookpad (in Japanese). 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 World Health Organisation / United Nations Environment Programme DTIE Chemicals Branch (2008). "Guidance for identifying populations at risk from mercury exposure" (PDF). p. 36. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. "平成15年6月3日に公表した「水銀を含有する魚介類等の 摂食に関する注意事項」について". Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (in Japanese).

Further reading

- Carwardine, M., Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises, Dorling Kindersley, 2000. ISBN 978-0-7513-2781-6.

- Williams, Heathcote, Whale Nation, New York, Harmony Books, 1988. ISBN 978-0-517-56932-0.

External links

Conservation, research and news:

- De Rohan, Anuschka. "Why dolphins are deep thinkers", The Guardian, July 3, 2003.

- The Dolphin Institute

- The Oceania Project, Caring for Whales and Dolphins

- Tursiops.org: Current Cetacean-related news

- Understanding Dolphins

Photos:

- Red Sea Spinner Dolphin – Photo gallery

- PBS NOVA: Dolphins: Close Encounters

- David's Dolphin Images

- Images of Wild Dolphins in the Red Sea

|