Condenser (laboratory)

A condenser is an apparatus or item of equipment used to condense (change the physical state of) a substance from its gaseous to its liquid state. In the laboratory, condensers are generally used in procedures done with organic liquids brought into gaseous state through heating with or without lowering the pressure (applying vacuum)—though applications in inorganic and other chemistry areas exist. While condensers can be applied at various scales, in the research, training, or discovery laboratory, one most often uses glassware designed to pass a vapor flow over an adjacent cooled chamber. In simplest form, such a condenser consists of a single glass tube with outside air providing cooling. A further simple form, the Liebig-type of condenser, involves concentric glass tubes, an inner one through which the hot gases pass, and an outer, "ported" chamber through which a cooling fluid passes, to reduce the gas temperature in the inner, to afford the condensation.

Depending on the application (chemical components being separated, and the required operating temperature) and the scale of the process (from very few microliters to process scales involving many liters), different types of condensers and means of cooling are used. Alongside the temperature differential and heat capacities of the cooling fluids (e.g., air, water, aqueous-organic co-solvents), the size of the cooling surface and the way in which gas (vapor) and condensing liquid states come into contact are critical in the choice or design of a condenser system. Since at least the 19th century, scientists have sought creative designs to maximize the surface area of vapor-liquid contact and heat exchange. Many types of laboratory condensers—simpler Liebig and Allihn, coiled Graham types, simple and Dimroth types of cold finger condensers, etc.—now common, have evolved to meet the practical need of larger cooling surfaces and controlled boiling and condensation in various procedures involving distillation, and a further very wide array of materials for "packing" simpler condensers to increase surface area (e.g., plass, ceramic, and metal beads, rings, wool, etc.) have been studied and applied.

Likewise, the configurations of laboratory apparatus involving condensers are many and varied, to cover low and high boiling solvents, simple and complex separations, etc. Several common process types based on the change of physical state provided by condensers can easily be described, including simple evaporations or "solvent stripping" (the bulk removal of all volatiles to leave behind concentrated solutes present in the original solution being evaporated), reflux operations (where the aim is to contain all volatiles while providing a constant process temperature established by the boiling point of the solvent system being used), and separation/distillation operations (where high theoretical plates provide for selective delivery of one or more volatile components of a complex "mixture" in a controlled fashion). The direction of vapor and condensate flows in the laboratory condenser chosen for each of these may vary (e.g., being countercurrent in reflux procedures, and concurrent in many simple distillation procedures), as do the optimal flow direction for the cooling fluid, etc. In all processes, condenser selection/design requires that the heat of entering vapor never overwhelm the condenser and cooling mechanism; as well, the thermal gradients and material flows established during the gas-liquid transition are critical aspects, so that as processes increase in scale from laboratory to pilot plant and beyond, the design of condenser systems becomes a precise engineering science.

Operation

A condenser is a piece of apparatus or equipment that can be used to condense, that is, to change the physical state of a substance from its gaseous to its liquid state; in the laboratory, it is generally used in procedures done with organic liquids brought into gaseous state through heating or application of vacuum (lowered pressure), though processes often involve at least trace amounts of the common inorganic component water, and can involve other inorganic substances as well. Condensers can be applied at various scales, from micro-scale (very few microliters) to process-scale (many liters), using laboratory glassware and occasionally metalware that accomplishes the cooling of the vapor generated by boiling (through heating or application of vacuum).[1]

In simplest form, a condenser can consist of a single tube of glass or metal, where the flow of outside air produces the cooling. In a further simple form, condensers consist of concentric glass tubes, with the tube through which the hot gases begin to pass running the length of the apparatus. The second tube defines an outer chamber through which air, water, or other cooling fluids can pass to reduce the temperature of the gasses to afford the condensation; hence, the outer tube (or, as designs become more complex, outer cooling chamber) has an inlet and an outlet to allow the cooling fluid to enter and exit.

The specific requirement that components in the solution being "fractionated" (divided into component fractions) have differing boiling points, and the varying demands of heat exchange for the various chemical processes using condensers have led to design of very wide varieties of types, with a general design theme being creative ways in which:

- first, the surface area for vapor-liquid interaction and heat exchange can be increased (which leads to an increased number of theoretical plates, a metric related to an apparatus's efficiency in separating components with smaller differences in boiling point), and

- second, ways in which to control common difficulties experienced in real distillations (such as "flooding and channeling", see below).[2]

The combination of these has taken the simple condenser concept through simple changes (e.g., addition, in Allihn-type condensers, of "bubbles" or undulations to the inner, straight vapor tube of the simple Liebig design, so that diethyl ether (b.p., ca. 35°C), could be accommodated), on to many unique condenser configurations, types of "packings" of the vapor space, and applied cooling media and mechanisms (see below). In this array of designs, the direction of vapor and condensate flows depends on the specific application (e.g., being countercurrent in reflux procedures, and concurrent in many simpler distillation procedures); the same is true with regard to the optimal flow direction for the cooling fluid (air, water, aqueous ethylene glycol co-solutions, etc.) relative to the direction of vapor flow. Note, while the traditional coolants, air and chilled tap water, have often been used without recirculation (i.e., allowed to exit to atmosphere or drain, respectively), larger scale operations and municipal and other regulations make engineered recirculation necessary, and it is always required for special cooling liquids, such as low temperature alcohols and co-solutions.

Designing and maintaining systems and processes using condensers requires that the heat of the entering vapor never overwhelm the ability of the chosen condenser and cooling mechanism; as well, the thermal gradients and material flows established are critical aspects, and as processes scale from laboratory to pilot plant and beyond, the design of condenser systems becomes a precise engineering science.[3]

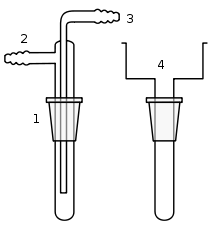

Use of condensers in chemical procedures—when not performed at fixed, lowered pressure by careful vacuum control—inevitably involves transiently fluctuating pressures within the apparatus, so that isolating the apparatus while allowing it to be an open rather than sealed system becomes a practical issue; this is particularly true, when chemical reactions are performed that are air- or moisture-sensitive. If the reaction or process using condensers cannot be left open to atmosphere, its isolation is accomplished in simplest fashion via drying tubes (an attached tube packed with desiccant) or other specially packed scavenging tubes, that allows gasses to pass, and so pressure equalization, but prevents entry of substances deleterious to the ongoing chemistry; alternatively, the apparatus can be vented through a "bubbler" that prevents entry of laboratory atmosphere either by allowing the internal volume to push and pull against a volume of resisting liquid (e.g., mineral or silicone oil), or by keeping a positive pressure of inert, "blanketing" gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) that vents through a similar volume of liquid. Attachment of such during tubes and bubblers can be direct, or indirect via gas/vacuum lines and manifolds.

Practically, in modern milliliter to liter-scale laboratory operations involving condensers, pieces of apparatus are often held together tightly by complementary, tapered "inner" and "outer" "joints" ground to produce very tight fits (augmented as necessary by PTFE rings or sleeves, or uniquely formulated greases or waxes; increasingly, other means of joint glass, such as threaded fittings with adapters, are used (some of which are also used across the range of process scales.

Examples of processes

Condensers are often used in reflux, where the hot solvent vapors of a liquid being heated are cooled and allowed to drip back.[4] This reduces the loss of solvent allowing the mixture to be heated for extended periods. Condensers are used in distillation to cool the hot vapors, condensing them into liquid for separate collection. For fractional distillation, an air or Vigreux condenser is usually used to slow the rate at which the hot vapors rise, giving a better separation between the different components in the distillate. For microscale distillation, the apparatus includes the "pot", and the condenser fused into one-piece, which reduces the hold-up volume, and obviates the need for ground glass joints preventing contamination by grease and precluding leaks.

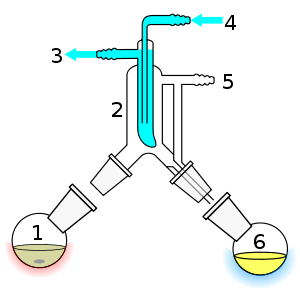

| Simple distillation with Minimal Added Theoretical Plates | [Legend] |

|---|---|

|

Shown in a cutaway view, blue indicating cooling flow and bath, red and yellow indicating heat. White areas in the short Vigreux section, 3, above boiling flask 2, and in Liebig condenser 5, and in vacuum take-off adapter 10, and receiving flask 8 represent the path through which vapor flows to the Liebig condenser (2→3→5) and the condensate flows from the condenser to a pre-weighed collection flask (5→10→8). Per usual, trapezoids represent matching ground glass joints allowing tight seals of apparatus parts. Impure liquid 15 is placed in boiling flask 2, and on a hotplate-stirrer (1, 13) equipped with silicone oil bath 14, and heated with stirring (11,12) or other otherwise prevented from "bumping" (see text). Vapor rises vertically, coming first in contact with the Vigreux indentations in distillation head 3, and when the reflux reaches the height of the downspout of the adapter (point of bulb of thermometer 4), vapor proceeds downward to contact Liebig condenser, 5, chilled by fluid flow through ports 6 and 7. As the warm gases boiled from flask 2 come into contact with the cold surface of condenser 2, the gaseous volatile changes state to liquid (condenses), and proceeds to the right, through the drip tip of take-off adapter 10 into collection flask 8. which is correspondingly cooled in bath 16 to prevent loss of product evaporation. After distillation is complete (often not to complete dryness of 1), the apparatus can be disassembled, a rough yield determined, and analysis for identity and purity as described above. Likewise,a as noted, distillation at ambient pressure has port 9 is attached to a drying tube while in a vacuum distillation, port 9 allows attachment of the vacuum pump. |

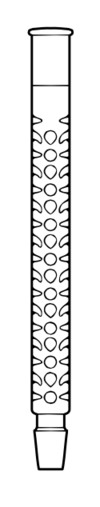

(finger indentations)

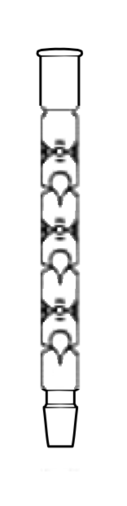

(floating inverted teardrops)

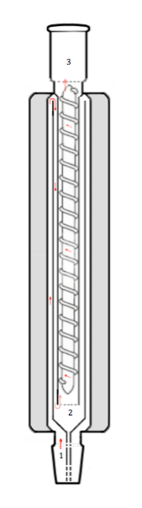

(concentric tube,

rod-and-spiral)

Air-cooled types

The simplest sort of condenser consists of a single tube wherein the heat of the vapour is conducted to the glass wall, which is only cooled by air; such air condensers are often used for condensation of high boiling liquids (i.e., for distillations at high temperatures, well above 100 °C), where columns can be used with or without packing (see below). Historically, the retort appearing in illustrations of the practice of alchemists is an apparatus that is essentially an unpacked air condenser. Liebig condensers are often used as air condensers, with air circulated rather than a liquid coolant (see next section).

A Vigreux column, named after Henri Vigreux, is a type of air condenser where a glass blower has modified the simple tube to include an abundance of downward-pointing indentations, thus dramatically increasing the surface area per unit length of the condenser. Such columns are often used to add the theoretical plates required in fractional distillation, and present added cost for their manufacture, which can include designs with or without an outer glass cylinder (jacket), open to air or allowing fluid circulation, or, to aid in insulation, an outer vacuum jacket.

A Snyder column is an extremely effective air-cooled column used in selected fractional distillations. It is a single glass tube with a series of circular indentations/restrictions in the walls of the cylinder (e.g., 3 or 6) in which rest, inverted, the same number of roughly tear-shaped, hollow, sealed glass stoppers; above each point where an inverted tear-shaped stopper rests, the cylinder has further Vigreux-type indentations, in this case serving to limit how high the glass stopper can be raised (by vapor flow) above its resting place, where, when not raised, it seals the circular opening created by the circular indentation.[5] These floating glass stoppers act as check valves, closing and opening with vapor flow, and enhancing vapor-condensate mixing. A standard application of Snyder columns, is as the condenser/fractionation column above a Kuderna-Danish concentrator, used to efficiently separate a low boiling extraction solvent such as methylene chloride from volatile but higher boiling extract components (e.g., after the extraction of organic contaminants in soil).[6]

A further air condenser is the Widmer column, developed as a doctoral research project by student Gustav Widmer at the ETH in the early 1920s, a complex type of air condenser combining Golodetz-type concentric tubes and the Dufton-type glass rod-and-wound-spiral at its center (see image).[7][1][8][9]

Fluid-cooled types

Liebig condenser

The condenser known as the Liebig type, a most basic circulating fluid-cooled design, was popularized by 19th century agricultural and biorganic chemist Justus von Liebig, who attributed its original design to the German pharmacist J.F.A. Gottling.[10] The design popularized by von Liebig consisted of an inner, straight tube surrounded by an outer straight tube, with the outer tube having ports for fluid inflow and outflow, and with the two tubes sealed in some fashion at the ends (eventually, by a blown glass ring seal). Its simplicity made it convenient to construct and inexpensive to manufacture, the higher heat capacity of the circulating water (vs. air) allowed for maintaining near to constant temperature in the condenser, and so the Liebig type proved to be the more efficient condenser—capable of condensing liquid from a much greater flow of incoming vapor—and therefore replaced retorts and air condensers. An added benefit of the simplicity of the straight inner tube design of this condenser type is that it can be "packed" with materials that increase the surface area (and so the number of theoretical plates of the distillation column, see section below), e.g., plastic, ceramic, and metal beads, rings, wool, etc. See Fractional Distillation.

West condenser

A variant of the Liebig condenser having a more slender design, with cone and socket. The fused-on narrower coolant jacket may render more efficient cooling with respect to coolant consumption.

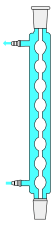

Allihn condenser

The Allihn condenser or "bulb condenser" or simply "reflux condenser" is named after Felix Richard Allihn.[11] The Allihn condenser consists of a long glass tube with a water jacket. A series of bulbs on the tube increases the surface area upon which the vapor constituents may condense. Ideally suited for laboratory-scale refluxing.

(cold finger,

spiral type)

Davies condenser

A Davies condenser, also known as a double surface condenser, is similar to the Liebig condenser, but with three concentric glass tubes instead of two. The coolant circulates in both the outer jacket and the central tube. This increases the cooling surface, so that the condenser can be shorter than an equivalent Liebig condenser.

Graham condenser

A Graham condenser (also Grahams or Inland Revenue condenser) has a coolant-jacketed spiral coil running the length of the condenser serving as the vapor/condensate path. This is not to be confused with the "coil condenser".

Coil condenser

A coil condenser is essentially a "Graham condenser" with an inverted coolant/vapor configuration. It has a spiral coil running the length of the condenser through which coolant flows, and this coolant coil is jacketed by the vapor/condensate path.

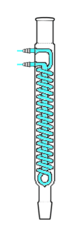

Dimroth condenser

A Dimroth condenser, named after Otto Dimroth, is somewhat similar to the "coil condenser"; it has an internal double spiral through which coolant flows such that the coolant inlet and outlet are both at the top. The vapors travel through the jacket from bottom to top. Dimroth condensers are more effective than conventional coil condensers. They are often found in rotary evaporators.

Spiral condenser

A spiral condenser has a spiral condensing tube with both inlet and outlet connections at top, on same side.[12] See Dimroth condenser.

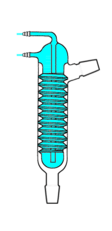

Friedrichs condenser

A Friedrichs condenser (sometimes incorrectly referred to as "Friedrich's" condenser), a spiraled finger condenser, was invented by Fritz Walter Paul Friedrichs, who published a design for this type of condenser in 1912.[13] It consists of a large, spiraled internal cold finger-type capillary tube disposed within a wide cylindrical housing. Coolant flows through the internal cold finger; accordingly, vapors rising up through the housing must pass along the spiraled path.

Packing of condensers

During a fractional distillation in the laboratory (or chemical plant), simple straight tubes can be packed with materials to increase surface area, and therefore the number of theoretical plates; in the same manner, the surface areas of simple laboratory glass condensers such as the Liebig can be filled to improve performance.[3] The same standard distillation packing materials can be used—glass beads, rings, or helices (e.g., Fenske rings), porcelain Raschig or Lessing rings, or metal packings of aluminum, copper, nickel, and stainless steel of most of the preceding shapes (e.g., metal Lessing and Fenske types); glass packings have as a further benefit their chemical inertness relevant to distillations of reactive chemicals (e.g., acid chlorides), while metal packings are easier to "tamp" to "ensure uniform lacking".[2][3]

Metal packing types can extend to wire packings of nichrome and inconel (akin to Podbielniak columns), to stainless steel gauze (Dixon rings), and indeed to any of the various special packing methods used in distillation (e.g., Hempel, Todd, and Stedman packing methods);[3] for instance, wire-packed columns of the Podbielniak type function by providing large surface areas for vapor-liquid interaction with capillary-like spaces that very evenly spread the condensed liquid, such that "channeling and flooding" in the column "are minimized", and giving, in one specific example, added theoretical plate counts of 1-2 per 5 cm of packed length.[2]

Alternative coolants

Solid dry ice or an acetone/dry ice mixture can be used in a cold finger as a coolant, which allows cooling of the vapour stream to below 0 °C (32 °F), a matter critical in the condensation of low boiling liquids (e.g., dimethyl ether, b.p. −23.6 °C [−10.5 °F]). Likewise, other chilled liquids can be circulated through typical water-cooled condensers; circulating coolants include water-ethylene glycol cosolvents (i.e., antifreeze solutions), and pure liquids such as ethanol, in either case pumped in a closed loop (recycling) fashion from a chiller-circulator under thermostatic control.

Further reading

- Heinz G. O. Becker, Werner Berger, Günter Domschke, et al., 2009, Organikum: organisch-chemisches Grundpraktikum (23rd German edn., compl. rev. updated), Weinheim:Wiley-VCH, ISBN 3-527-32292-2, see , accessed 25 February 2015.

- Heinz G. O. Becker, Werner Berger, Günter Domschke, Egon Fanghänel, Jürgen Faust, Mechthild Fischer, Frithjof Gentz, Karl Gewald, Reiner Gluch, Roland Mayer, Klaus Müller, Dietrich Pavel, Hermann Schmidt, Karl Schollberg, Klaus Schwetlick, Erika Seiler & Günter Zeppenfeld, 1973, Organicum: Practical Handbook of Organic Chemistry (1st English ed., P.A. Ongly, Ed., B.J. Hazzard, Transl., cf. 5th German edn., 1965), Reading, Mass.:Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-05504-X, see , accessed 25 February 2015.

- Armarego, W.L.F; Chai, Christina (2012). Purification of Laboratory Chemicals (7th ed.). Oxford, U.K.: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 8–14. ISBN 978-0-12-382162-1.

- Coker, A. Kayode; Ludwig, Ernest E. (2010). "Distillation (Chapter 10) and Packed Towers (Chapter 14)". Ludwig's Applied Process Design for Chemical and Petrochemical Plants: Volume 2: Distillation, packed towers, petroleum fractionation, gas processing and dehydration (4th ed.). New York: Elsevier-Gulf Professional Publishing. ISBN 978-0-08-094209-4, pp 1-268 (Ch. 10), 679-686 (Ch. 10 refs.), 483-678 (Ch. 14), 687-690 (Ch. 14 refs.), 691-696 (Biblio.).

- Leonard, John; Lygo, Barry; Procter, Garry (1994). Advanced Practical Organic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-7487-4071-0.

- Vogel, A.I.; Tatchell, A.R. (1996). Vogel's textbook of practical organic chemistry (5th ed.). Longman or Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-582-46236-6, or 4th edition.

- Tietze, Lutz F; Eicher, Theophil (1986). Reactions and Syntheses in the Organic Chemistry Laboratory (1st ed.). University Science Books. ISBN 978-0-935702-50-7.

- Shriver, D. F.; Drezdzon, M. A. (1986). The Manipulation of Air-Sensitive Compounds. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-86773-9.

- Krell, Erich (1982). Handbook of Laboratory Distillation: With an Introduction into the Pilot Plant Distillation. Techniques and instrumentation in Analytical Chemistry (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-99723-4.

- Stage, F. (1947). "Die Kolonnen zur Laboratoriumsdestillation. Eine Übersicht über den Entwicklungsstand der Kolonnen zur Destillation im Laboratorium". Angewandte Chemie 19 (7): 175–183. doi:10.1002/ange.19470190701.

- Kyrides, L. P. (1940). "Fumaryl Chloride". Organic Syntheses 20: 51. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.020.0051.

- Pasto, Daniel J; Johnson, Carl R (1979). Laboratory Text for Organic Chemistry: A Source Book of Chemical and Physical Techniques. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-521302-5.

Gallery of further condenser types

-

Cold fingers

Gallery of further condenser applications

-

simple cold finger, in sublimation apparatus

See also

References

- 1 2 Wiberg, Kenneth B. (1960). Laboratory Technique in Organic Chemistry. McGraw-Hill series in advanced chemistry. New York: McGraw Hill. ASIN B0007ENAMY.

- 1 2 3 Armarego, W.L.F; Chai, Christina (2012). Purification of Laboratory Chemicals (7th ed.). Oxford, U.K.: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-0-12-382162-1.

- 1 2 3 4 E.g., Ludwig, Ernest E (1997). "Distillation (Chapter 8), and Packed Towers (Chapter 9)". Applied Process Design for Chemical and Petrochemical Plants: Volume 2 (3rd ed.). New York: Elsevier-Gulf Professional Publishing. ISBN 978-0-08-052737-6, pp 1-229 (Ch. 8) and 230-415 (Ch. 9), esp. pp. 255, 277ff, 247f, 230ff, 1-14.

- ↑ Zhi Hua (Frank) Yang (2005). "Design methods for [industrial] reflux condensers". Chemical Processing (online). Retrieved 2015-02-02.

- ↑ Gunther, F.A.; Blinn, R.C.; Kolbezen, M.J.; Barkley, J.H.; Harris, W.D.; Simon, H.G. (1951). "Microestimation of 2-(p-tert-Butylphenoxy)isopropyl-2-chloroethyl Sulfite Residues". Analytical Chemistry 23 (12): 1835–1842. doi:10.1021/ac60060a033..

- ↑ Wauchope, R. Don. (1975). "Solvent recovery and reuse with the Kuderna-Danish evaporator". Analytical Chemistry 47 (11): 1879. doi:10.1021/ac60361a033.

- ↑ Here, the original Swiss copyright-protected images of Widmer were redrawn, except that the stoppered seal of the original outer dead air space design was modernized to a ring seal, the J-shaped discharge tube was omitted for simplicity of description, and top and bottom ports were converted to appear as tapered ground joints. See Widmer, Gustav (1923). Über die fraktionierte Destillation kleiner Substanzmengen (Ph.D.) (in German). Zürich, der Schweiz: der Eidgenössischen Technischen Hochschule (ETH). doi:10.3929/ethz-a-000090805.

- ↑ Widmer, Gustav (1924). "Über die fraktionierte Destillation kleiner Substanzmengen". Helvetica Chimica Acta 7 (1): 59–61. doi:10.1002/hlca.19240070107.

- ↑ A so-called modified WIdmer column design was reported as being in wide use, but undocumented, by Kyrides, L. P. (1940). "Fumaryl Chloride". Organic Syntheses 20: 51. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.020.0051.

- ↑ Gottling in turn is known to have made improvements to a 1771 design by German chemist C.E.Weigel, and it appears that the "Liebig" design was also described independently in recognizable form by French scientist P. J. Poisonnier in 1779, and Finnish chemist Johan Gadolin in 1791. E.g., Jensen, William B. (2006). "The Origin of the Liebig Condenser". Journal of Chemical Education 83: 23. Bibcode:2006JChEd..83...23J. doi:10.1021/ed083p23..

- ↑ Sella, Andrea (2010). "Allihn's Condenser". Chemistry World 2010 (5): 66.

- ↑ "Condenser, spiral". Ace Glass Laboratory Glassware. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ Fritz Friedrichs (1912). "Some new forms of laboratory apparatus". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 34 (11): 1509–14. doi:10.1021/ja02212a012.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||