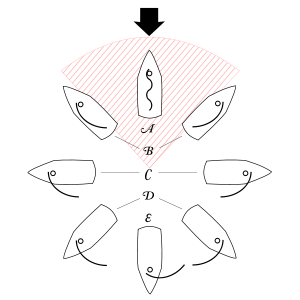

Point of sail

A. in irons (into the wind) Shaded: "no-go zone"

B. close-hauled

C. beam reach

D. broad reach

E. running

Point of sail is a term used to describe a sailing boat's orientation in relation to the wind direction.

Except when head to wind, a boat will be on either a port tack or a starboard tack. If the wind is coming from anywhere on the port side, the boat is on port tack. Likewise if the wind is coming from the starboard side, the boat is on starboard tack. For purposes of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea and the Racing Rules of Sailing, the wind is assumed to be coming from the side opposite that which the mainsail boom is carried, if the vessel is so rigged. The direction of sail is used for square-rigged vessels.

No-go zone

Sailboats cannot sail directly into the environmental wind, nor on a course that is too close to the direction from which the wind is blowing. The range of directions into which a boat cannot sail is called the 'no-go zone'. Its width depends on the design of the boat, its rig, and its sails, as well as on the wind strength and the sea state. Depending on the boat and the conditions, the no-go zone may be from 30 to 50 degrees either side of the wind, a 60 to 100 degree area centered on the wind direction.

When attempting to sail into the no-go zone, the boat's sails do not produce enough drive to maintain way or forward momentum through the water. Therefore the boat will eventually coast to a stop, with the rudder becoming less and less effective at controlling the direction of travel.

A sailboat's ability to sail close to the wind is referred to as its "pointing" ability. A yacht designed primarily for racing can typically point within 30 or at worst 40 degrees from the wind direction, whereas one designed for cruising may only be able to point within 40 to 50 degrees of the wind direction. Working boats may not be able to point this well and square rigged vessels certainly cannot. The size of the no-go zone varies, but all sailboats have one.

A boat turns through the no-go zone as it tacks. Since the boat is passing through the no-go zone, it must maintain momentum until it has turned all the way through this area. If a boat loses steerage way before it exits the no-go zone, it is said to be "in irons" and may stop, return to the original tack, or begin to travel slowly backwards.

In irons

If the boat attempts to tack too slowly, or otherwise loses forward motion while heading into the wind, the boat will coast to a stop and the lack of water flow over the rudder will cause the sailor to lose the ability to steer the boat. Stopped head-to-wind, a sailboat is said to be "in irons". To recover from being in irons, one or more sails can be "backwinded" by sheeting or pushing them to one side. A sail backwinded to one side of the boat will tend to push the bow to the other side, and the boat may "pay off" in that direction so that the sails can be trimmed again and normal sailing resumed. A sail backed further aft may make a boat begin to "make sternway," or make way backwards. If this is possible the rudder can be used to steer the boat out of the no-go zone.[1]

Close-hauled

A boat is said to be sailing close-hauled (also called beating or working to windward) when its sails are trimmed in tightly and it is sailing as close to the wind as it can without entering the no go zone. This point of sail lets the boat travel diagonally to the wind direction, or 'upwind'. Sails act in a similar fashion to wings; the flow of air over the outside of the curve creates lift that pulls the boat through the water. A boat is considered to be "pinching" or "feathering" if the helmsman tries to sail above an efficient close-hauled course and the sails begin to luff slightly. This can be an effective technique to maintain control of the boat on a windy day by 'de-powering', or stalling the sail's lift slightly, but is otherwise inefficient.

Reaching

When the boat is traveling approximately perpendicular to the wind, this is called reaching. A "close" reach is somewhat toward the wind, and "broad" reach is slightly away from the wind (a "beam" reach is with the wind at a right angle to the boat). For most modern sailboats, reaching is the fastest way to travel. On some boats, the beam reach is the fastest point of sail; on others, a broad reach is faster.

Close reach

This is an upwind angle between close-hauled and a beam reach.

Beam reach

This is a course steered at right angles to the wind on either port or starboard tack.

Broad reach

The wind is coming from behind the boat at an angle. This represents a range of wind angles between beam reach and running downwind. The sails are eased out away from the boat, but not as much as on a run or dead run (downwind run).

Running downwind

On this point of sail (also called running before the wind), the wind is coming from directly behind the boat. Running can be dangerous to those on board in the event of an accidental jibe.

When running, the mainsail is eased out as far as it will go. The jib will collapse because the mainsail blocks its wind, and must either be lowered and replaced by a spinnaker, or set instead on the windward side of the boat. Running with the jib to windward is known as 'gull wing', 'goose wing', 'butterflying' or 'wing and wing'. A genoa gull-wings well, especially if stabilized by a whisker pole, which is similar to but lighter than a spinnaker pole.

Some racing sailboats set a spinnaker when sailing any point of sail from beam reach to a run. In classes where spinnakers are not permitted, poled-out genoas are often used when running downwind. In College and High School style racing, where neither spinnakers nor poles are permitted, the jib is winged opposite the main and the boat heeled to windward to help maintain sail shape without a pole. When running downwind for protracted periods, for example when ocean-crossing in steady trade winds, cruisers sometimes set twin poled-out jibs without a mainsail. All of these options are more stable and require less trimming effort than a spinnaker.

Steering can be difficult when running because there is less pressure on the tiller to provide feedback to the helmsman, and the boat is less stable, meaning the boat may go off course more easily than on other points of sail. This tendency to turn off course when running can be dangerous. If a boat turns to leeward too far, or sails "by the lee", the boat can jibe accidentally if the lee side of the sail catches the wind, causing the boom to swing across the boat quickly. A preventer can be used on yachts to help avoid this. Some boats, particularly smaller racing dinghies like the Laser, sail "by the lee" very well, but most sailboats should be careful to avoid this.

Also when sailing on a dead downwind run an inexperienced or inattentive sailor can easily misjudge the real strength of the wind since the boat speed subtracts directly from the true wind speed and this makes the apparent wind less. In addition the sea conditions may also seem milder than they are as developing white caps ahead are shielded from view by the back of the waves. When changing course in a brisk wind from a run to a reach or a beat, a sailboat that seemed under control can instantly become over-canvassed and in danger of a sudden broach.

In high performance boats such as planing monohulls and fast catamarans, better speed towards a leeward mark can be made by gybing downwind. The extra distance covered can be more than compensated for by the increase in speed.

See also

References

Bibliography

- Rousmaniere, John, The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Simon & Schuster, 1999

- Chapman Book of Piloting (various contributors), Hearst Corporation, 1999

- Herreshoff, Halsey (consulting editor), The Sailor’s Handbook, Little Brown and Company, 1983

- Seidman, David, The Complete Sailor, International Marine, 1995

- Jobson, Gary, Sailing Fundamentals, Simon & Schuster, 1987

| ||||||||