Dodo

| Dodo Temporal range: Late Holocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dodo skeleton cast and model based on modern research, at Oxford University Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Columbiformes |

| Family: | Columbidae |

| Subfamily: | †Raphinae |

| Genus: | †Raphus Brisson, 1760 |

| Species: | †R. cucullatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Raphus cucullatus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| |

| Location of Mauritius (in blue) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) is an extinct flightless bird that was endemic to the island of Mauritius, east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Its closest genetic relative was the also extinct Rodrigues solitaire, the two forming the subfamily Raphinae of the family of pigeons and doves. The closest extant relative of the dodo is the Nicobar pigeon. A white dodo was once thought to have existed on the nearby island of Réunion, but this is now thought to have been confusion based on the Réunion ibis and paintings of white dodos.

Subfossil remains show the dodo was about 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) tall and may have weighed 10.6–21.1 kg (23–47 lb) in the wild. The dodo's appearance in life is evidenced only by drawings, paintings, and written accounts from the 17th century. Because these vary considerably, and because only some illustrations are known to have been drawn from live specimens, its exact appearance in life remains unresolved. Similarly, little is known with certainty about its habitat and behaviour.[2] It has been depicted with brownish-grey plumage, yellow feet, a tuft of tail feathers, a grey, naked head, and a black, yellow, and green beak. It used gizzard stones to help digest its food, which is thought to have included fruits, and its main habitat is believed to have been the woods in the drier coastal areas of Mauritius. One account states its clutch consisted of a single egg. It is presumed that the dodo became flightless because of the ready availability of abundant food sources and a relative absence of predators on Mauritius.

The first recorded mention of the dodo was by Dutch sailors in 1598. In the following years, the bird was hunted by sailors, their domesticated animals, and invasive species introduced during that time. The last widely accepted sighting of a dodo was in 1662. Its extinction was not immediately noticed, and some considered it to be a mythical creature. In the 19th century, research was conducted on a small quantity of remains of four specimens that had been brought to Europe in the early 17th century. Among these is a dried head, the only soft tissue of the dodo that remains today. Since then, a large amount of subfossil material has been collected on Mauritius, mostly from the Mare aux Songes swamp. The extinction of the dodo within less than a century of its discovery called attention to the previously unrecognised problem of human involvement in the disappearance of entire species. The dodo achieved widespread recognition from its role in the story of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, and it has since become a fixture in popular culture, often as a symbol of extinction and obsolescence. It is frequently used as a mascot on Mauritius.

Taxonomy

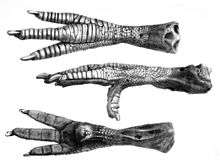

The dodo was variously declared a small ostrich, a rail, an albatross, or a vulture, by early scientists.[3] In 1842, Johannes Theodor Reinhardt proposed that dodos were ground pigeons, based on studies of a dodo skull he had discovered in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Denmark.[4] This view was met with ridicule, but was later supported by Hugh Edwin Strickland and Alexander Gordon Melville in their 1848 monograph The Dodo and Its Kindred, which attempted to separate myth from reality.[5] After dissecting the preserved head and foot of the specimen at the Oxford University Museum and comparing it with the few remains then available of the extinct Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria) they concluded that the two were closely related. Strickland stated that although not identical, these birds shared many distinguishing features of the leg bones, otherwise known only in pigeons.[6]

Strickland and Melville established that the dodo was anatomically similar to pigeons in many features. They pointed to the very short keratinous portion of the beak, with its long, slender, naked basal part. Other pigeons also have bare skin around their eyes, almost reaching their beak, as in dodos. The forehead was high in relation to the beak, and the nostril was located low on the middle of the beak and surrounded by skin, a combination of features shared only with pigeons. The legs of the dodo were generally more similar to those of terrestrial pigeons than of other birds, both in their scales and in their skeletal features. Depictions of the large crop hinted at a relationship with pigeons, in which this feature is more developed than in other birds. Pigeons generally have very small clutches, and the dodo is said to have laid a single egg. Like pigeons, the dodo lacked the vomer and septum of the nostrils, and it shared details in the mandible, the zygomatic bone, the palate, and the hallux. The dodo differed from other pigeons mainly in the small size of the wings and the large size of the beak in proportion to the rest of the cranium.[6]

Throughout the 19th century, several species were classified as congeneric with the dodo, including the Rodrigues solitaire and the Réunion solitaire, as Didus solitarius and Raphus solitarius, respectively (Didus and Raphus being names for the dodo genus used by different authors of the time). An atypical 17th-century description of a dodo and bones found on Rodrigues, now known to have belonged to the Rodrigues solitaire, led Abraham Dee Bartlett to name a new species, Didus nazarenus, in 1852.[7] Based on solitaire remains, it is now a synonym of that species.[8] Crude drawings of the red rail of Mauritius were also misinterpreted as dodo species; Didus broeckii and Didus herberti.[9]

For many years the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire were placed in a family of their own, the Raphidae (formerly Dididae), because their exact relationships with other pigeons were unresolved. Each was also placed in its own monotypic family (Raphidae and Pezophapidae, respectively), as it was thought that they had evolved their similarities independently.[10] Osteological and DNA analysis has since led to the dissolution of the family Raphidae, and the dodo and solitaire are now placed in their own subfamily, Raphinae, within the family Columbidae.[11]

Etymology

One of the original names for the dodo was the Dutch "Walghvogel", first used in the journal of Vice Admiral Wybrand van Warwijck, who visited Mauritius during the Second Dutch Expedition to Indonesia in 1598.[2] Walghe means "tasteless", "insipid", or "sickly", and vogel means "bird". The name was translated into German as Walchstök or Walchvögel, by Jakob Friedlib.[12] The original Dutch report titled Waarachtige Beschryving was lost, but the English translation survived:[13]

On their left hand was a little island which they named Heemskirk Island, and the bay it selve they called Warwick Bay... Here they taried 12. daies to refresh themselues, finding in this place great quantity of foules twice as bigge as swans, which they call Walghstocks or Wallowbirdes being very good meat. But finding an abundance of pigeons & popinnayes [parrots], they disdained any more to eat those great foules calling them Wallowbirds, that is to say lothsome or fulsome birdes.[14][15]

Another account from that voyage, perhaps the first to mention the dodo, states that the Portuguese referred to them as penguins. The meaning may not have been derived from penguin (the Portuguese referred to them as "fotilicaios" at the time), but from pinion, a reference to the small wings.[2] The crew of the Dutch ship Gelderland referred to the bird as "Dronte" (meaning "swollen") in 1602, a name that is still used in some languages.[16] This crew also called them "griff-eendt" and "kermisgans", in reference to fowl fattened for the Kermesse festival in Amsterdam, which was held the day after they anchored on Mauritius.[17]

The etymology of the word dodo is unclear. Some ascribe it to the Dutch word dodoor for "sluggard", but it is more probably related to Dodaars, which means either "fat-arse" or "knot-arse", referring to the knot of feathers on the hind end.[18] The first record of the word Dodaars is in Captain Willem Van West-Zanen's journal in 1602.[19] The English writer Sir Thomas Herbert was the first to use the word dodo in print in his 1634 travelogue, claiming it was referred to as such by the Portuguese, who had visited Mauritius in 1507.[17] Another Englishman, Emmanuel Altham, had used the word in a 1628 letter, in which he also claimed the origin was Portuguese. The name "dodar" was introduced into English at the same time as dodo, but was only used until the 18th century.[20] As far as is known, the Portuguese never mentioned the bird. Nevertheless, some sources still state that the word dodo derives from the Portuguese word doudo (currently doido), meaning "fool" or "crazy". It has also been suggested that dodo was an onomatopoeic approximation of the bird's call, a two-note pigeon-like sound resembling "doo-doo".[21]

The Latin name cucullatus ("hooded") was first used by Juan Eusebio Nieremberg in 1635 as Cygnus cucullatus, in reference to Carolus Clusius's 1605 depiction of a dodo. In his 18th-century classic work Systema Naturae, Carl Linnaeus used cucullatus as the specific name, but combined it with the genus name Struthio (ostrich).[6] Mathurin Jacques Brisson coined the genus name Raphus (referring to the bustards) in 1760, resulting in the current name Raphus cucullatus. In 1766, Linnaeus coined the new binomial Didus ineptus (meaning "inept dodo"). This has become a synonym of the earlier name because of nomenclatural priority.[22]

Evolution

In 2002, American geneticist Beth Shapiro and colleagues analysed the DNA of the dodo for the first time. Comparison of mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12S rRNA sequences isolated from a tarsal of the Oxford specimen and a femur of a Rodrigues solitaire confirmed their close relationship and their placement within the Columbidae. The genetic evidence was interpreted as showing the Southeast Asian Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica) to be their closest living relative, followed by the crowned pigeons (Goura) of New Guinea, and the superficially dodo-like tooth-billed pigeon (Didunculus strigirostris) from Samoa (its scientific name refers to its dodo-like beak). This clade consists of generally ground-dwelling island endemic pigeons. The following cladogram shows the dodo's closest relationships within the Columbidae, based on Shapiro et al., 2002:[23][24]

| |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

.jpg)

A similar cladogram was published in 2007, inverting the placement of Goura and Dicunculus and including the pheasant pigeon (Otidiphaps nobilis) and the thick-billed ground pigeon (Trugon terrestris) at the base of the clade.[25] The DNA used in these studies was obtained from the Oxford specimen, and since this material is degraded, and no usable DNA has been extracted from subfossil remains, these findings still need to be independently verified.[26] Based on behavioural and morphological evidence, Jolyon C. Parish proposed that the dodo and Rodrigues solitaire should be placed in the Gourinae subfamily along with the Groura pigeons and others, in agreement with the genetic evidence.[27] In 2014, DNA of the only known specimen of the recently extinct spotted green pigeon (Caloenas maculata) was analysed, and it was found to be a close relative of the Nicobar pigeon, and thus also the dodo and Rodrigues solitaire.[28]

The 2002 study indicated that the ancestors of the dodo and the solitaire diverged around the Paleogene-Neogene boundary. The Mascarene Islands (Mauritius, Réunion, and Rodrigues), are of volcanic origin and are less than 10 million years old. Therefore, the ancestors of both birds probably remained capable of flight for a considerable time after the separation of their lineage.[29] The Nicobar and spotted green pigeon were placed at the base of a lineage leading to the Raphinae, which indicates the flightless raphines had ancestors that were able to fly, were semi-terrestrial, and inhabited islands. This in turn supports the hypothesis that the ancestors of those birds reached the Mascarene islands by island hopping from South Asia.[28] The lack of mammalian herbivores competing for resources on these islands allowed the solitaire and the dodo to attain very large sizes.[30] The dodo lost the ability to fly owing to the lack of mammalian predators on Mauritius.[31] Another large, flightless pigeon, the Viti Levu giant pigeon (Natunaornis gigoura), was described in 2001 from subfossil material from Fiji. It was only slightly smaller than the dodo and the solitaire, and it too is thought to have been related to the crowned pigeons.[32]

Description

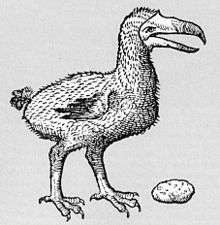

As no complete dodo specimens exist, its external appearance, such as plumage and colouration, is hard to determine.[2] Illustrations and written accounts of encounters with the dodo between its discovery and its extinction (1598–1662) are the primary evidence for its external appearance.[33] According to most representations, the dodo had greyish or brownish plumage, with lighter primary feathers and a tuft of curly light feathers high on its rear end. The head was grey and naked, the beak green, black and yellow, and the legs were stout and yellowish, with black claws.[34] The bird was sexually dimorphic: males were larger and had proportionally longer beaks. The beak was up to 23 centimetres (9.1 in) in length and had a hooked point.[35]

Subfossil remains and remnants of the birds that were brought to Europe in the 17th century show that they were very large birds, 1 metre (3 feet 3 inches) tall, and possibly weighing up to 23 kilograms (51 lb). The higher weights have been attributed to birds in captivity; weights in the wild were estimated to have been in the range 10.6–21.1 kg (23–47 lb).[36] A later estimate gives an average weight as low as 10.2 kg (22 lb).[37] This has been questioned, and there is still some controversy.[38][39] A 2016 study estimated the weight at 10.6 to 14.3 kg (23 to 32 lb), based on CT scans of composite skeletons.[40] It has been suggested that the weight depended on the season, and that individuals were fat during cool seasons, but less so during hot.[41] A study of the few remaining feathers on the Oxford specimen head showed that they were pennaceous rather than plumaceous (downy) and most similar to those of other pigeons.[42]

Many of the skeletal features that distinguish the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire, its closest relative, from pigeons have been attributed to their flightlessness. The pelvic elements were thicker than those of flighted pigeons to support the higher weight, and the pectoral region and the small wings were paedomorphic, meaning that they were underdeveloped and retained juvenile features. The skull, trunk and pelvic limbs were peramorphic, meaning that they changed considerably with age. The dodo shared several other traits with the Rodrigues solitaire, such as features of the skull, pelvis, and sternum, as well as their large size. It differed in other aspects, such as being more robust and shorter than the solitaire, having a larger skull and beak, a rounded skull roof, and smaller orbits. The dodo's neck and legs were proportionally shorter, and it did not possess an equivalent to the knob present on the solitaire's wrists.[35]

Contemporary descriptions

Most contemporary descriptions of the dodo are found in ship's logs and journals of the Dutch East India Company vessels that docked in Mauritius when the Dutch Empire ruled the island. These records were used as guides for future voyages.[26] Few contemporary accounts are reliable, as many seem to be based on earlier accounts, and none were written by scientists.[2]

One of the earliest accounts, from van Warwijck's 1598 journal, describes the bird thus:

Blue parrots are very numerous there, as well as other birds; among which are a kind, conspicuous for their size, larger than our swans, with huge heads only half covered with skin as if clothed with a hood. These birds lack wings, in the place of which 3 or 4 blackish feathers protrude. The tail consists of a few soft incurved feathers, which are ash coloured. These we used to call 'Walghvogel', for the reason that the longer and oftener they were cooked, the less soft and more insipid eating they became. Nevertheless their belly and breast were of a pleasant flavour and easily masticated.[43]

One of the most detailed descriptions is by Sir Thomas Herbert in A Relation of Some Yeares Travaille into Afrique and the Greater Asia from 1634:

First here only and in Dygarrois [Rodrigues, likely referring to the solitaire] is generated the Dodo, which for shape and rareness may antagonize the Phoenix of Arabia: her body is round and fat, few weigh less than fifty pound. It is reputed more for wonder than for food, greasie stomackes may seeke after them, but to the delicate they are offensive and of no nourishment. Her visage darts forth melancholy, as sensible of Nature's injurie in framing so great a body to be guided with complementall wings, so small and impotent, that they serve only to prove her bird. The halfe of her head is naked seeming couered with a fine vaile, her bill is crooked downwards, in midst is the trill [nostril], from which part to the end tis a light green, mixed with pale yellow tincture; her eyes are small and like to Diamonds, round and rowling; her clothing downy feathers, her train three small plumes, short and inproportionable, her legs suiting her body, her pounces sharpe, her appetite strong and greedy. Stones and iron are digested, which description will better be conceived in her representation.[44]

Contemporary depictions

.jpg)

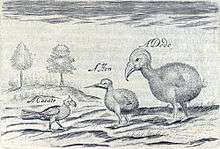

The travel journal of the Dutch ship Gelderland (1601–1603), rediscovered in the 1860s, contains the only known sketches of living or recently killed specimens drawn on Mauritius. They have been attributed to the professional artist Joris Joostensz Laerle, who also drew other now-extinct Mauritian birds, and to a second, less refined artist.[45] Apart from these sketches, it is unknown how many of the twenty or so 17th-century illustrations of the dodos were drawn from life or from stuffed specimens, which affects their reliability.[2]

All post-1638 depictions appear to be based on earlier images, around the time reports mentioning dodos became rarer. Differences in the depictions led authors such as Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans and Masauji Hachisuka to speculate about sexual dimorphism, ontogenic traits, seasonal variation, and even the existence of different species, but these theories are not accepted today. Because details such as markings of the beak, the form of the tail feathers, and colouration vary from account to account, it is impossible to determine the exact morphology of these features, whether they signal age or sex, or if they even reflect reality.[46] Dodo specialist Julian Hume argued that the nostrils of the living dodo would have been slits, as seen in the Gelderland, Cornelis Saftleven, Crocker Art Gallery, and Ustad Mansur images. According to this claim, the gaping nostrils often seen in paintings indicate that taxidermy specimens were used as models.[2]

The traditional image of the dodo is of a very fat and clumsy bird, but this view may be exaggerated. The general opinion of scientists today is that many old European depictions were based on overfed captive birds or crudely stuffed specimens.[47] It has also been suggested that the images might show dodos with puffed feathers, as part of display behaviour.[37] The Dutch painter Roelant Savery was the most prolific and influential illustrator of the dodo, having made at least ten depictions, often showing it in the lower corners. A famous painting of his from 1626, now called Edwards's Dodo as it was once owned by the ornithologist George Edwards, has since become the standard image of a dodo. It is housed in the Natural History Museum, London. The image shows a particularly fat bird and is the source for many other dodo illustrations.[48]

An Indian Mughal painting rediscovered in St. Petersburg in the 1950s shows a dodo along with native Indian birds.[49] It depicts a slimmer, brownish bird, and its discoverer A. Iwanow and dodo specialist Julian Hume regard it as one of the most accurate depictions of the living dodo; the surrounding birds are clearly identifiable and depicted with appropriate colouring.[50] It is believed to be from the 17th century and has been attributed to artist Ustad Mansur. The bird depicted probably lived in the menagerie of Mughal Emperor Jahangir, located in Surat, where English traveller Peter Mundy also claimed to have seen dodos.[2] In 2014, another Indian illustration of a dodo was reported, but it was found to be derivative of an 1836 German illustration.[51]

Behaviour and ecology

Little is known of the behaviour of the dodo, as most contemporary descriptions are very brief.[36] Based on weight estimates, it has been suggested the male could reach the age of 21, and the female 17.[35] Studies of the cantilever strength of its leg bones indicate that it could run quite fast.[36] Unlike the Rodrigues solitaire, there is no evidence that the dodo used its wings in intraspecific combat. Though some dodo bones have been found with healed fractures, it had weak pectoral muscles and more reduced wings in comparison. The dodo may instead have used its large, hooked beak in territorial disputes. Since Mauritius receives more rainfall and has less seasonal variation than Rodrigues, which would have affected the availability of resources on the island, the dodo would have less reason to evolve aggressive territorial behaviour. The Rodrigues solitaire was therefore probably the more aggressive of the two.[52]

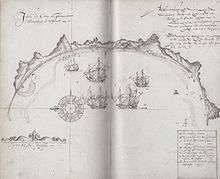

The preferred habitat of the dodo is unknown, but old descriptions suggest that it inhabited the woods on the drier coastal areas of south and west Mauritius. This view is supported by the fact that the Mare aux Songes swamp is close to the sea in south-eastern Mauritius.[53] Such a limited distribution across the island could well have contributed to its extinction.[54] A 1601 map from the Gelderland journal shows a small island off the coast of Mauritius where dodos were caught. Julian Hume has suggested this island was in Tamarin Bay, on the west coast of Mauritius.[55] Subfossil bones have also been found inside caves in highland areas, indicating that it once occurred on mountains. Work at the Mare aux Songes swamp has shown that its habitat was dominated by tambalacoque and Pandanus trees and endemic palms.[41]

Many endemic species of Mauritius became extinct after the arrival of humans, so the ecosystem of the island is badly damaged and hard to reconstruct. Before humans arrived, Mauritius was entirely covered in forests, but very little remains of them today, because of deforestation.[56] The surviving endemic fauna is still seriously threatened.[57] The dodo lived alongside other recently extinct Mauritian birds such as the flightless red rail, the broad-billed parrot, the Mascarene grey parakeet, the Mauritius blue pigeon, the Mauritius owl, the Mascarene coot, the Mauritian shelduck, the Mauritian duck, and the Mauritius night heron. Extinct Mauritian reptiles include the saddle-backed Mauritius giant tortoise, the domed Mauritius giant tortoise, the Mauritian giant skink, and the Round Island burrowing boa. The small Mauritian flying fox and the snail Tropidophora carinata lived on Mauritius and Réunion, but vanished from both islands. Some plants, such as Casearia tinifolia and the palm orchid, have also become extinct.[58]

Diet

A 1631 Dutch document, rediscovered in 1887 but now lost, is the only account of the dodo's diet and also mentions that it used its beak for defence:

These mayors are superb and proud. They displayed themselves to us with stiff and stern faces, and wide-open mouths. Jaunty and audacious of gait, they would scarcely move a foot before us. Their war weapon was their mouth, with which they could bite fiercely; their food was fruit; they were not well feathered but abundantly covered with fat. Many of them were brought onboard to the delight of us all.[59]

In addition to fallen fruits, the dodo probably subsisted on nuts, seeds, bulbs, and roots.[60] It has also been suggested that the dodo might have eaten crabs and shellfish, like their relatives the crowned pigeons. Its feeding habits must have been versatile, since captive specimens were probably given a wide range of food on the long sea journeys.[61] Anthonie Oudemans suggested that as Mauritius has marked dry and wet seasons, the dodo probably fattened itself on ripe fruits at the end of the wet season to survive the dry season, when food was scarce; contemporary reports describe the bird's "greedy" appetite. France Staub suggested that they mainly fed on palm fruits, and he attempted to correlate the fat-cycle of the dodo with the fruiting regime of the palms.[19]

Several contemporary sources state that the dodo used Gastroliths (gizzard stones) to aid digestion. The English writer Sir Hamon L'Estrange witnessed a live bird in London and described it as follows:

About 1638, as I walked London streets, I saw the picture of a strange looking fowle hung out upon a clothe and myselfe with one or two more in company went in to see it. It was kept in a chamber, and was a great fowle somewhat bigger than the largest Turkey cock, and so legged and footed, but stouter and thicker and of more erect shape, coloured before like the breast of a young cock fesan, and on the back of a dunn or dearc colour. The keeper called it a Dodo, and in the ende of a chymney in the chamber there lay a heape of large pebble stones, whereof hee gave it many in our sight, some as big as nutmegs, and the keeper told us that she eats them (conducing to digestion), and though I remember not how far the keeper was questioned therein, yet I am confident that afterwards she cast them all again.[62]

It is not known how the young were fed, but related pigeons provide crop milk. Contemporary depictions show a large crop, which was probably used to add space for food storage and to produce crop milk. It has been suggested that the maximum size attained by the dodo and the solitaire was limited by the amount of crop milk they could produce for their young during early growth.[63]

In 1973, the tambalacoque, also known as the dodo tree, was thought to be dying out on Mauritus, to which it is endemic. There were supposedly only 13 specimens left, all estimated to be about 300 years old. Stanley Temple hypothesised that it depended on the dodo for its propagation, and that its seeds would germinate only after passing through the bird's digestive tract. He claimed that the tambalacoque was now nearly coextinct because of the disappearance of the dodo.[64] Temple overlooked reports from the 1940s that found that tambalacoque seeds germinated, albeit very rarely, without being abraded during digestion.[65] Others have contested his hypothesis and suggested that the decline of the tree was exaggerated, or seeds were also distributed by other extinct animals such as Cylindraspis tortoises, fruit bats or the broad-billed parrot.[66] According to Wendy Strahm and Anthony Cheke, two experts in the ecology of the Mascarene Islands, the tree, while rare, has germinated since the demise of the dodo and numbers several hundred, not 13 as claimed by Temple, hence discrediting Temple's view as to the dodo and the tree's sole survival relationship.[67]

It has been suggested that the broad-billed parrot may have depended on dodos and Cylindraspis tortoises to eat palm fruits and excrete their seeds, which became food for the parrots. Anodorhynchus macaws depended on now-extinct South American megafauna in the same way, but now rely on domesticated cattle for this service.[68]

Reproduction

As it was flightless and terrestrial and there were no mammalian predators or other kinds of natural enemy on Mauritius, the dodo probably nested on the ground.[69] The account by François Cauche from 1651 is the only description of the egg and the call:

I have seen in Mauritius birds bigger than a Swan, without feathers on the body, which is covered with a black down; the hinder part is round, the rump adorned with curled feathers as many in number as the bird is years old. In place of wings they have feathers like these last, black and curved, without webs. They have no tongues, the beak is large, curving a little downwards; their legs are long, scaly, with only three toes on each foot. It has a cry like a gosling, and is by no means so savoury to eat as the Flamingos and Ducks of which we have just spoken. They only lay one egg which is white, the size of a halfpenny roll, by the side of which they place a white stone the size of a hen's egg. They lay on grass which they collect, and make their nests in the forests; if one kills the young one, a grey stone is found in the gizzard. We call them Oiseaux de Nazaret. The fat is excellent to give ease to the muscles and nerves.[6]

Cauche's account is problematic, since it also mentions that the bird he was describing had three toes and no tongue, unlike dodos. This led some to believe that Cauche was describing a new species of dodo ("Didus nazarenus"). The description was most probably mingled with that of a cassowary, and Cauche's writings have other inconsistencies.[70] A mention of a "young ostrich" taken on board a ship in 1617 is the only other reference to a possible juvenile dodo.[59] An egg claimed to be that of a dodo is stored in the museum of East London, South Africa. It was donated by Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, whose great aunt had received it from a captain who claimed to have found it in a swamp on Mauritius. In 2010, the curator of the museum proposed using genetic studies to determine its authenticity.[71] It may instead be an aberrant ostrich egg.[21]

Because of the possible single-egg clutch and the bird's large size, it has been proposed that the dodo was K-selected, meaning that it produced a low number of altricial offspring, which required parental care until they matured. Some evidence, including the large size and the fact that tropical and frugivorous birds have slower growth rates, indicates that the bird may have had a protracted development period.[35] The fact that no juvenile dodos have been found in the Mare aux Songes swamp, where most dodo remains have been excavated, may indicate that they produced little offspring, that they matured rapidly, that the breeding grounds were far away from the swamp, or that the risk of miring was seasonal.[72]

Relationship with humans

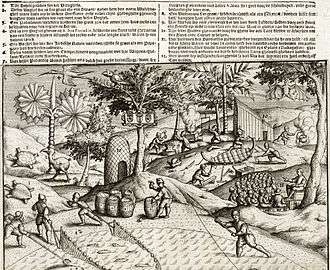

Mauritius had previously been visited by Arab vessels in the Middle Ages and Portuguese ships between 1507 and 1513, but was settled by neither. No records of dodos by these are known, although the Portuguese name for Mauritius, "Cerne (swan) Island", may have been a reference to dodos.[73] The Dutch Empire acquired Mauritius in 1598, renaming it after Maurice of Nassau, and it was used for the provisioning of trade vessels of the Dutch East India Company henceforward.[74] The earliest known accounts of the dodo were provided by Dutch travelers during the Second Dutch Expedition to Indonesia, led by admiral Jacob van Neck in 1598. They appear in reports published in 1601, which also contain the first published illustration of the bird.[75] Since the first sailors to visit Mauritius had been at sea for a long time, their interest in these large birds was mainly culinary. The 1602 journal by Willem Van West-Zanen of the ship Bruin-Vis mentions that 24–25 dodos were hunted for food, which were so large that two could scarcely be consumed at mealtime, their remains being preserved by salting.[76] An illustration made for the 1648 published version of this journal, showing the killing of dodos, a dugong, and possibly Mascarene grey parakeets, was captioned with a Dutch poem,[77] here in Hugh Strickland's 1848 translation:

For food the seamen hunt the flesh of feathered fowl,

They tap the palms, and round-rumped dodos they destroy,

The parrot's life they spare that he may peep and howl,

And thus his fellows to imprisonment decoy.[1]

- ^ Strickland & Melville 1848, pp. 15.

Some early travellers found dodo meat unsavoury, and preferred to eat parrots and pigeons; others described it as tough but good. Some hunted dodos only for their gizzards, as this was considered the most delicious part of the bird. Dodos were easy to catch, but hunters had to be careful not to be bitten by their powerful beaks.[78]

The appearance of the dodo and the red rail led Peter Mundy to speculate, 230 years before Charles Darwin's theory of evolution:

Of these 2 sorts off fowl afforementionede, For oughtt wee yett know, Not any to bee Found out of this Iland, which lyeth aboutt 100 leagues From St. Lawrence. A question may bee demaunded how they should bee here and Not elcewhere, beeing soe Farer From other land and can Neither fly or swymme; whither by Mixture off kindes producing straunge and Monstrous formes, or the Nature of the Climate, ayer and earth in alltring the First shapes in long tyme, or how.[16]

Dodos transported abroad

The dodo was found interesting enough that living specimens were sent to Europe and the East. The number of transported dodos that reached their destinations alive is uncertain, and it is unknown how they relate to contemporary depictions and the few non-fossil remains in European museums. Based on a combination of contemporary accounts, paintings, and specimens, Julian Hume has inferred that at least eleven transported dodos reached their destinations alive.[79]

Hamon L'Estrange's description of a dodo that he saw in London in 1638 is the only account that specifically mentions a live specimen in Europe. In 1626 Adriaen van de Venne drew a dodo that he claimed to have seen in Amsterdam, but he did not mention if it was alive, and his depiction is reminiscent of Savery's Edwards's Dodo. Two live specimens were seen by Peter Mundy in Surat, India, between 1628 and 1634, one of which may have been the individual painted by Ustad Mansur around 1625.[2] In 1628, Emmanuel Altham visited Mauritius and sent a letter to his brother in England:

Right wo and lovinge brother, we were ordered by ye said councell to go to an island called Mauritius, lying in 20d. of south latt., where we arrived ye 28th of May; this island having many goates, hogs and cowes upon it, and very strange fowles, called by ye portingalls Dodo, which for the rareness of the same, the like being not in ye world but here, I have sent you one by Mr. Perce, who did arrive with the ship William at this island ye 10th of June. [In the margin of the letter] Of Mr. Perce you shall receive a jarr of ginger for my sister, some beades for my cousins your daughters, and a bird called a Dodo, if it live.[80]

Whether the dodo survived the journey is unknown, and the letter was destroyed by fire in the 19th century.[81] The earliest known picture of a dodo specimen in Europe is from a c. 1610 collection of paintings depicting animals in the royal menagerie of Emperor Rudolph II in Prague. This collection includes paintings of other Mauritian animals as well, including a red rail. The dodo, which may be a juvenile, seems to have been dried or embalmed, and had probably lived in the emperor's zoo for a while together with the other animals. That whole stuffed dodos were present in Europe indicates they had been brought alive and died there; it is unlikely that taxidermists were on board the visiting ships, and spirits were not yet used to preserve biological specimens. Most tropical specimens were preserved as dried heads and feet.[79]

One dodo was reportedly sent as far as Nagasaki, Japan in 1647, but it was long unknown whether it arrived.[68] Contemporary documents first published in 2014 proved the story, and showed that it had arrived alive. It was meant as a gift, and, despite its rarity, was considered of equal value to a white deer and a bezoar stone. It is the last recorded live dodo in captivity.[82]

Extinction

Like many animals that evolved in isolation from significant predators, the dodo was entirely fearless of humans. This fearlessness and its inability to fly made the dodo easy prey for sailors.[83] Although some scattered reports describe mass killings of dodos for ships' provisions, archaeological investigations have found scant evidence of human predation. Bones of at least two dodos were found in caves at Baie du Cap that sheltered fugitive slaves and convicts in the 17th century, which would not have been easily accessible to dodos because of the high, broken terrain.[11] The human population on Mauritius (an area of 1,860 km2 or 720 sq mi) never exceeded 50 people in the 17th century, but they introduced other animals, including dogs, pigs, cats, rats, and crab-eating macaques, which plundered dodo nests and competed for the limited food resources.[41] At the same time, humans destroyed the forest habitat of the dodos. The impact of the introduced animals on the dodo population, especially the pigs and macaques, is currently considered more severe than that of hunting.[84] Rats were perhaps not much of a threat to the nests, since dodos would have been used to dealing with local land crabs.[85]

It has been suggested that the dodo may already have been rare or localised before the arrival of humans on Mauritius, since it would have been unlikely to become extinct so rapidly if it had occupied all the remote areas of the island.[54] A 2005 expedition found subfossil remains of dodos and other animals killed by a flash flood. Such mass mortalities would have further jeopardised a species already in danger of becoming extinct.[86]

Some controversy surrounds the date of their extinction. The last widely accepted record of a dodo sighting is the 1662 report by shipwrecked mariner Volkert Evertsz of the Dutch ship Arnhem, who described birds caught on a small islet off Mauritius, now suggested to be Amber Island:

These animals on our coming up to them stared at us and remained quiet where they stand, not knowing whether they had wings to fly away or legs to run off, and suffering us to approach them as close as we pleased. Amongst these birds were those which in India they call Dod-aersen (being a kind of very big goose); these birds are unable to fly, and instead of wings, they merely have a few small pins, yet they can run very swiftly. We drove them together into one place in such a manner that we could catch them with our hands, and when we held one of them by its leg, and that upon this it made a great noise, the others all on a sudden came running as fast as they could to its assistance, and by which they were caught and made prisoners also.[87]

The dodos on this islet may not necessarily have been the last members of the species.[88] The last claimed sighting of a dodo was reported in the hunting records of Isaac Johannes Lamotius in 1688. Statistical analysis of these records by Roberts and Solow gives a new estimated extinction date of 1693, with a 95% confidence interval of 1688–1715. The authors also pointed out that because the last sighting before 1662 was in 1638, the dodo was probably already quite rare by the 1660s, and thus a disputed report from 1674 by an escaped slave cannot be dismissed out of hand.[89]

Anthony Cheke pointed out that some descriptions after 1662 use the names "Dodo" and "Dodaers" when referring to the red rail, indicating that they had been transferred to it after the disappearance of the dodo itself.[90] Cheke therefore points to the 1662 description as the last credible observation. A 1668 account by English traveller John Marshall, who used the names "Dodo" and "Red Hen" interchangeably for the red rail, mentioned that the meat was "hard", which echoes the description of the meat in the 1681 account.[91] Even the 1662 account has been questioned by Errol Fuller, as the reaction to distress cries matches what was described for the red rail.[92] Until this explanation was proposed, a description of "dodos" from 1681 was thought to be the last account, and that date still has proponents.[93] Recently accessible Dutch manuscripts indicate that no dodos were seen by settlers in 1664–1674.[94] It is unlikely the issue will ever be resolved, unless late reports mentioning the name alongside a physical description are rediscovered.[85] The IUCN Red List accepts Cheke's rationale for choosing the 1662 date, taking all subsequent reports to refer to red rails. In any case, the dodo was probably extinct by 1700, about a century after its discovery in 1598.[1][91] The Dutch left Mauritius in 1710, but by then the dodo and most of the large terrestrial vertebrates there had become extinct.[41]

Even though the rareness of the dodo was reported already in the 17th century, its extinction was not recognised until the 19th century. This was partly because, for religious reasons, extinction was not believed possible until later proved so by Georges Cuvier, and partly because many scientists doubted that the dodo had ever existed. It seemed altogether too strange a creature, and many believed it a myth. The bird was first used as an example of human-induced extinction in Penny Magazine in 1833.[95]

Physical remains

17th-century specimens

The only extant remains of dodos taken to Europe in the 17th century are a dried head and foot in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, a foot once housed in the British Museum but now lost, a skull in the University of Copenhagen Zoological Museum, and an upper jaw and leg bones in the National Museum, Prague. The last two were rediscovered and identified as dodo remains in the mid-19th century.[96] Several stuffed dodos were also mentioned in old museum inventories, but none are known to have survived.[97] Apart from these remains, a dried foot, which belonged to the Dutch professor Pieter Pauw, was mentioned by Carolus Clusius in 1605. Its provenance is unknown, and it is now lost, but it may have been collected during the Van Neck voyage.[2]

The only known soft tissue remains, the Oxford head (specimen OUM 11605) and foot, belonged to the last known stuffed dodo, which was first mentioned as part of the Tradescant collection in 1656 and was moved to the Ashmolean Museum in 1659. It has been suggested that this might be the remains of the bird that Hamon L'Estrange saw in London.[2] Many sources state that the museum burned the stuffed dodo around 1755 because of severe decay, saving only the head and leg. Statute 8 of the museum states "That as any particular grows old and perishing the keeper may remove it into one of the closets or other repository; and some other to be substituted."[98] The deliberate destruction of the specimen is now believed to be a myth; it was removed from exhibition to preserve what remained of it. This remaining soft tissue has since degraded further; the head was dissected by Strickland and Melville, separating the skin from the skull in two halves. The foot is in a skeletal state, with only scraps of skin and tendons. Very few feathers remain on the head. It is probably a female, as the foot is 11% smaller and more gracile than that of the London specimen, yet appears to be fully grown.[99]

The dried London foot, first mentioned in 1665, and transferred to the British Museum in the 18th century, was displayed next to Savery's Edwards's Dodo painting until the 1840s, and it too was dissected by Strickland and Melville. It was not posed in a standing posture, which suggests that it was severed from a fresh specimen, not a mounted one. By 1896 it was mentioned as being without its integuments, and only the bones are believed to remain today, though its present whereabouts are unknown.[2]

The Copenhagen skull (specimen ZMUC 90-806) is known to have been part of the collection of Bernardus Paludanus in Enkhuizen until 1651, when it was moved to the museum in Gottorf Castle, Schleswig.[100] After the castle was occupied by Danish forces in 1702, the museum collection was assimilated into the Royal Danish collection. The skull was rediscovered by J. T. Reinhardt in 1840. Based on its history, it may be the oldest known surviving remains of a dodo brought to Europe in the 17th century.[2] It is 13 mm (0.51 in) shorter than the Oxford skull, and may have belonged to a female.[35] It was mummified, but the skin has perished.[41]

The front part of a skull (specimen NMP P6V-004389, a syntype of this species) in the National Museum of Prague was found in 1850 among the remains of the Böhmisches Museum. Other elements supposedly belonging to this specimen have been listed in the literature, but it appears only the partial skull was ever present.[2][101] It may be what remains of one of the stuffed dodos known to have been at the menagerie of Emperor Rudolph II, possibly the specimen painted by Hoefnagel or Savery there.[102]

Subfossil specimens

Until 1860, the only known dodo remains were the four incomplete 17th-century specimens. Philip Burnard Ayres found the first subfossil bones in 1860, which were sent to Richard Owen at the British Museum, who did not publish the findings. In 1863, Owen requested the Mauritian Bishop Vincent Ryan to spread word that he should be informed if any dodo bones were found.[3] In 1865, George Clark, the government schoolmaster at Mahébourg, finally found an abundance of subfossil dodo bones in the swamp of Mare aux Songes in Southern Mauritius, after a 30-year search inspired by Strickland and Melville's monograph.[2] In 1866, Clark explained his procedure to The Ibis, an ornithology journal: he had sent his coolies to wade through the centre of the swamp, feeling for bones with their feet. At first they found few bones, until they cut away herbage that covered the deepest part of the swamp, where they found many fossils.[103] The swamp yielded the remains of over 300 dodos, but very few skull and wing bones, possibly because the upper bodies were washed away or scavenged while the lower body was trapped. The situation is similar to many finds of moa remains in New Zealand marshes.[104] Most dodo remains from the Mare aux Songes have a medium to dark brown colouration.[72]

Clark's reports about the finds rekindled interest in the bird. Sir Richard Owen and Alfred Newton both wanted to be first to describe the post-cranial anatomy of the dodo, and Owen bought a shipment of dodo bones originally meant for Newton, which led to rivalry between the two. Owen described the bones in Memoir on the Dodo in October 1866, but erroneously based his reconstruction on the Edwards's Dodo painting by Savery, making it too squat and obese. In 1869 he received more bones and corrected its stance, making it more upright. Newton moved his focus to the Réunion solitaire instead. The remaining bones not sold to Owen or Newton were auctioned off or donated to museums.[3] In 1889, Théodor Sauzier was commissioned to explore the "historical souvenirs" of Mauritius and find more dodo remains in the Mare aux Songes. He was successful, and also found remains of other extinct species.[105]

In October 2005, after a hundred years of neglect, a part of the Mare aux Songes swamp was excavated by an international team of researchers. To prevent malaria, the British had covered the swamp with hard core during their rule over Mauritius, which had to be removed. Many remains were found, including bones of at least 17 dodos in various stages of maturity (though no juveniles), and several bones obviously from the skeleton of one individual bird, which have been preserved in their natural position.[106] These findings were made public in December 2005 in the Naturalis museum in Leiden. 63% of the fossils found in the swamp belonged to turtles of the extinct Cylindraspis genus, and 7.1% belonged to dodos, which had been deposited within several centuries, 4,000 years ago.[107] Subsequent excavations suggested that dodos and other animals became mired in the Mare aux Songes while trying to reach water during a long period of severe drought about 4,200 years ago.[106] Furthermore, cyanobacteria thrived in the conditions created by the excrements of animals gathered around the swamp, which died of intoxication, dehydration, trampling, and miring.[108] Though many small skeletal elements were found during the recent excavations of the swamp, few were found during the 19th century, probably owing to the employment of less refined methods when collecting.[72] In June 2007, adventurers exploring a cave in Mauritius discovered the most complete and best-preserved dodo skeleton ever found. The specimen was nicknamed "Fred" after the finder.[109]

Louis Etienne Thirioux, an amateur naturalist at Port Louis, also found many dodo remains around 1900 from several locations. They included the first articulated specimen, which is also the only subfossil dodo found outside the Mare aux Songes, and the only remains of a juvenile specimen, a now lost tarsometatarsus.[2][41] The former specimen was found in 1904 in a cave near Le Pouce mountain, and is the only complete skeleton of an individual dodo, and includes the only preserved kneecaps of the bird. Thirioux donated it to the Museum Desjardins (now Natural History Museum at Mauritius Institute), where it is still on display.[110][111] In 2014, this specimen was the basis for the first 3-D reconstruction of a complete dodo skeleton, by using 3-D laser scanning technology. The reconstruction was displayed in Berlin at the 74th Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology.[112][113][114]

Worldwide, 26 museums have significant holdings of dodo material, almost all found in the Mare aux Songes. The Natural History Museum, American Museum of Natural History, Cambridge University Museum of Zoology, the Senckenberg Museum, and others have almost complete skeletons, assembled from the dissociated subfossil remains of several individuals.[115] In 2011, a wooden box containing dodo bones from the Edwardian era was rediscovered at the Grant Museum at University College London during preparations for a move. They had been stored with crocodile bones until then.[116]

The white dodo

The supposed "white dodo" (or "solitaire") of Réunion is now considered an erroneous conjecture based on contemporary reports of the Réunion ibis and 17th-century paintings of white, dodo-like birds by Pieter Withoos and Pieter Holsteyn that surfaced in the 19th century. The confusion began when Willem Ysbrandtszoon Bontekoe, who visited Réunion around 1619, mentioned fat, flightless birds that he referred to as "Dod-eersen" in his journal, though without mentioning their colouration. When the journal was published in 1646, it was accompanied by an engraving of a dodo from Savery's "Crocker Art Gallery sketch".[117] A white, stocky, and flightless bird was first mentioned as part of the Réunion fauna by Chief Officer J. Tatton in 1625. Sporadic mentions were subsequently made by Sieur Dubois and other contemporary writers.[118]

Baron Edmond de Sélys Longchamps coined the name Raphus solitarius for these birds in 1848, as he believed the accounts referred to a species of dodo. When 17th-century paintings of white dodos were discovered by 19th-century naturalists, it was assumed they depicted these birds. Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans suggested that the discrepancy between the paintings and the old descriptions was that the paintings showed females, and that the species was therefore sexually dimorphic.[119] Some authors also believed the birds described were of a species similar to the Rodrigues solitaire, as it was referred to by the same name, or even that there were white species of both dodo and solitaire on the island.[120]

The Pieter Withoos painting, which was discovered first, appears to be based on an earlier painting by Pieter Holsteyn, three versions of which are known to have existed. According to Hume, Cheke, and Valledor de Lozoya, it appears that all depictions of white dodos were based on Roelant Savery's 1611 painting Landscape with Orpheus and the animals, or on copies of it. The painting shows a whitish specimen and was apparently based on a stuffed specimen then in Prague; a walghvogel described as having a "dirty off-white colouring" was mentioned in an inventory of specimens in the Prague collection of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, to whom Savery was contracted at the time (1607–1611). Savery's several later images all show greyish birds, possibly because he had by then seen another specimen. Cheke and Hume believe the painted specimen was white, owing to albinism.[102] Valledor de Lozoya has instead suggested that the light plumage was a juvenile trait, a result of bleaching of old taxidermy specimens, or simply artistic license.[121]

In 1987, scientists described fossils of a recently extinct species of ibis from Réunion with a relatively short beak, Borbonibis latipes, before a connection to the solitaire reports had been made.[122] Cheke suggested to one of the authors, Francois Moutou, that the fossils may have been of the Réunion solitaire, and this suggestion was published in 1995. The ibis was reassigned to the genus Threskiornis, now combined with the specific epithet solitarius from the binomial R. solitarius.[123] Birds of this genus are also white and black with slender beaks, fitting the old descriptions of the Réunion solitaire. No fossil remains of dodo-like birds have ever been found on the island.[102]

Cultural significance

The dodo's significance as one of the best-known extinct animals and its singular appearance led to its use in literature and popular culture as a symbol of an outdated concept or object, as in the expression "dead as a dodo," which has come to mean unquestionably dead or obsolete. Similarly, the phrase "to go the way of the dodo" means to become extinct or obsolete, to fall out of common usage or practice, or to become a thing of the past.[124] "Dodo" is also a slang term for a stupid, dull-witted person, as it was supposedly stupid and easily caught.[125][126]

The dodo appears frequently in works of popular fiction, and even before its extinction, it was featured in European literature, as symbol for exotic lands, and of gluttony, due to its apparent fatness.[127] In 1865, the same year that George Clark started to publish reports about excavated dodo fossils, the newly vindicated bird was featured as a character in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. It is thought that he included the dodo because he identified with it and had adopted the name as a nickname for himself because of his stammer, which made him accidentally introduce himself as "Do-do-dodgson", his legal surname.[95] The book's popularity made the dodo a well-known icon of extinction.[128]

The dodo is used as a mascot for many kinds of products, especially in Mauritius.[129] The dodo appears as a supporter on the coat of arms of Mauritius.[84] It is also used as a watermark on all Mauritian rupee banknotes.[130] A smiling dodo is the symbol of the Brasseries de Bourbon, a popular brewer on Réunion, whose emblem displays the white species once thought to have lived there.[131]

The dodo is used to promote the protection of endangered species by environmental organisations, such as the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and the Durrell Wildlife Park.[132] In 2011, the nephilid spider Nephilengys dodo, which inhabits the same woods as the dodo once did, was named after the bird to raise awareness of the urgent need for protection of the Mauritius biota.[133] The Center for Biological Diversity gives an annual 'Rubber Dodo Award', to "those who have done the most to destroy wild places, species and biological diversity".[134]

The name dodo has been immortalised by scientists naming genetic elements, honoring the dodo's flightless nature. A fruitfly gene within a region of a chromosome required for flying ability was named "dodo".[135] In addition, a defective transposable element family from Phytophthora infestans was named DodoPi as it contained mutations that eliminated the element's ability to jump to new locations in a chromosome.[136]

In 2009, a previously unpublished 17th-century Dutch illustration of a dodo went for sale at Christie's and was expected to sell for £6,000.[137] It is unknown whether the illustration was based on a specimen or on a previous image. It sold for £44,450.[138]

The poet Hilaire Belloc included the following poem about the dodo in his Bad Child's Book of Beasts from 1896:

The Dodo used to walk around,

And take the sun and air.

The sun yet warms his native ground –

The Dodo is not there!The voice which used to squawk and squeak

Is now for ever dumb –

Yet may you see his bones and beak

All in the Mu-se-um.[1]

- ^ Belloc 1896, pp. 27–30.

See also

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 IUCN Red List 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Hume 2006.

- 1 2 3 Hume, Cheke & McOran-Campbell 2009.

- ↑ Reinhardt 1842–1843.

- ↑ Baker & Bayliss 2002.

- 1 2 3 4 Strickland & Melville 1848, pp. 4–112.

- ↑ Newton 1865.

- ↑ Lydekker 1891, p. 128.

- ↑ Milne-Edwards 1869.

- ↑ Storer 1970.

- 1 2 Janoo 2005.

- ↑ Parish 2013, p. 5,137.

- ↑ Parish 2013, p. 3-4.

- ↑ Hakluyt 2013, p. 253.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 51.

- 1 2 Fuller 2001, pp. 194–203.

- 1 2 Cheke & Hume 2008, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, pp. 17–18.

- 1 2 Staub 1996.

- ↑ Cheke & Hume 2008, p. 276.

- 1 2 Fuller 2002, p. 43.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, pp. 147–149.

- ↑ Shapiro et al. 2002.

- ↑ BBC 2002.

- ↑ Pereira et al. 2007.

- 1 2 Hume 2012.

- ↑ Naish, D. (2014). "A Review of 'The Dodo and the Solitaire: A Natural History'". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34 (2): 489. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.803977.

- 1 2 Heupink, Tim H; van Grouw, Hein; Lambert, David M (2014). "The mysterious Spotted Green Pigeon and its relation to the Dodo and its kindred". BMC Evolutionary Biology 14 (1): 136. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-136.

- ↑ Cheke & Hume 2008, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ McNab 1999.

- ↑ Fuller 2001, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ Worthy 2001.

- ↑ Fuller 2003, p. 48.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Livezey 1993.

- 1 2 3 Kitchener August 1993.

- 1 2 Angst, Buffetaut & Abourachid March 2011.

- ↑ Louchart & Mourer-Chauviré 2011.

- ↑ Angst, Buffetaut & Abourachid April 2011.

- ↑ . doi:10.7717/peerj.1432. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hume & Walters 2012, pp. 134–136.

- ↑ Brom & Prins 1989.

- ↑ Rothschild 1907, p. 172.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 62.

- ↑ Hume 2003.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Kitchener June 1993.

- ↑ Mason 1992, pp. 46–49.

- ↑ Iwanow 1958.

- ↑ Dissanayake 2004.

- ↑ Richon, Emmanuel; Winters, Ria (2014). "The intercultural dodo: a drawing from the School of Bundi, Rājasthān". Historical Biology: 1–8. doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.961450.

- ↑ Hume & Steel 2013.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 23.

- 1 2 Fuller 2002, p. 41.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 54.

- ↑ Cheke 1987.

- ↑ Temple 1974.

- ↑ Cheke & Hume 2008, pp. 49–52.

- 1 2 Cheke & Hume 2008, p. 162.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 42.

- ↑ Cheke & Hume 2008, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 69.

- ↑ Storer 2005.

- ↑ Temple 1977.

- ↑ Hill 1941.

- ↑ Herhey 2004.

- ↑ Witmer & Cheke 1991.

- 1 2 Cheke & Hume 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Cheke & Hume 2008, p. 27.

- ↑ Laing 2010.

- 1 2 3 Meijer et al. 2012, pp. 177–184.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 17.

- ↑ Schaper & Goupille 2003, p. 93.

- ↑ Hume, Martill & Dewdney 2004.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 56.

- ↑ Hume, J. P. (2007). "Reappraisal of the parrots (Aves: Psittacidae) from the Mascarene Islands, with comments on their ecology, morphology, and affinities" (PDF). Zootaxa 1513: 4–21.

- ↑ Cheke & Hume 2008, pp. 77–78.

- 1 2 Cheke & Hume 2008, pp. 81–83.

- ↑ Macmillan 2000, p. 83.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 60.

- ↑ Winters, R.; Hume, J. P. (2014). "The dodo, the deer and a 1647 voyage to Japan". Historical Biology 27 (2): 1. doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.884566.

- ↑ BBC 2002-11-20.

- 1 2 Fryer 2002.

- 1 2 Cheke & Hume 2008, p. 79.

- ↑ Cocks 2006.

- ↑ Cheke 2004.

- ↑ Roberts, D. L. (2013). "Refuge-effect hypothesis and the demise of the Dodo". Conservation Biology 27 (6): 1478–1480. doi:10.1111/cobi.12134. PMID 23992554.

- ↑ Roberts & Solow 2003.

- ↑ Cheke, A. S. (1987). "An ecological history of the Mascarene Islands, with particular reference to extinctions and introductions of land vertebrates". In Diamond (ed.), A. W. Studies of Mascarene Island Birds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–89. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511735769.003. ISBN 978-0-521-11331-1.

- 1 2 Cheke 2006.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, pp. 70–73.

- ↑ Jackson, A. (2013). "Added credence for a late Dodo extinction date". Historical Biology 26 (6): 1–3. doi:10.1080/08912963.2013.838231.

- ↑ Cheke, Anthony S. (2014). "Speculation, statistics, facts and the Dodo's extinction date". Historical Biology 27 (5): 1–10. doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.904301.

- 1 2 Turvey & Cheke 2008.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, pp. 116–129.

- ↑ Ovenell 1992.

- ↑ MacGregor 2001.

- ↑ Hume, Datta & Martill 2006.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 123.

- ↑ Jiří, M. (2012). "Extinct and nearly extinct birds in the collections of the National Museum, Prague, Czech Republic". Journal of the National Museum (Prague) National History Series 181: 105–106.

- 1 2 3 Hume & Cheke 2004.

- ↑ Clark 1866.

- ↑ Hume 2005.

- ↑ Newton & Gadow 1893.

- 1 2 Rijsdijk et al. 2011.

- ↑ Rijsdijk et al. 2009.

- ↑ De Boer, E. J.; Velez, M. I.; Rijsdijk, K. F.; De Louw, P. G.; Vernimmen, T. J.; Visser, P. M.; Tjallingii, R.; Hooghiemstra, H. (2015). "A deadly cocktail: How a drought around 4200 cal. Yr BP caused mass mortality events at the infamous 'dodo swamp' in Mauritius". The Holocene 25 (5): 758–771. doi:10.1177/0959683614567886.

- ↑ Ravilious 2007.

- ↑ Gillespie & Clague 2009, p. 231.

- ↑ Richards 2012, p. 15.

- ↑ The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 2014.

- ↑ Bryner 2014.

- ↑ Choi 2014.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, pp. 123–129.

- ↑ Kennedy 2011.

- ↑ Cheke & Hume 2008, p. 30.

- ↑ Rothschild 1907, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Rothschild 1919.

- ↑ Cheke & Hume 2008, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ de Lozoya 2003.

- ↑ Mourer-Chauviré & Moutou 1987.

- ↑ Mourer-Chauviré, Bour & Ribes 1995.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, p. 13.

- ↑ "dodo". Dictionary.com. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ↑ Palmatier, Robert Allen (1995). Speaking of Animals: A Dictionary of Animal Metaphors. Greenwood. p. 113. ISBN 978-0313294907. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ↑ Lawrence, N. (2015). "Assembling the dodo in early modern natural history". The British Journal for the History of Science 48 (3): 1. doi:10.1017/S0007087415000011.

- ↑ Mayell 2002.

- ↑ Fuller 2002, pp. 140–153.

- ↑ "Mauritius new 25- and 50-rupee polymer notes confirmed". banknotenews.com.

- ↑ Cheke & Hume 2008, p. 31.

- ↑ Bhookhun 2006.

- ↑ Kuntner & Agnarsson 2011.

- ↑ "Pesticide Peddler Monsanto Wins 2015 Rubber Dodo Award" (Press release). Center for Biological Diversity. 5 November 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ↑ Maleszka et al. 1996.

- ↑ Ah Fong & Judelson 2004.

- ↑ Jamieson 2009.

- ↑ Christie's 2009.

Sources

- Angst, D.; Buffetaut, E.; Abourachid, A. (2011). "The end of the fat dodo? A new mass estimate for Raphus cucullatus". Naturwissenschaften 98 (3): 233–236. Bibcode:2011NW.....98..233A. doi:10.1007/s00114-010-0759-7. PMID 21240603.

- Angst, D.; Buffetaut, E.; Abourachid, A. (April 2011). "In defence of the slim dodo: A reply to Louchart and Mourer-Chauviré". Naturwissenschaften 98 (4): 359. Bibcode:2011NW.....98..359A. doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0772-5.

- Baker, R. A.; Bayliss, R. A. (February 2002). "Alexander Gordon Melville (1819–1901): The Dodo, Raphus cucullatus (L., 1758) and the genesis of a book". Archives of Natural History 29: 109–118. doi:10.3366/anh.2002.29.1.109. [1]

- BBC (28 February 2002). "DNA yields dodo family secrets". BBC News (London). Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- BBC (20 November 2003). "Scientists pinpoint dodo's demise". BBC News (London). Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- Belloc, H. (1896). The Bad Child's Book of Beasts. London: Duckworth.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Raphus cucullatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- Brom, T. G.; Prins, T. G. (June 1989). "Microscopic investigation of feather remains from the head of the Oxford dodo, Raphus cucullatus". Journal of Zoology 218 (2): 233–246. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1989.tb02535.x.

- Cheke, A. S. (1987). "The legacy of the dodo—conservation in Mauritius". Oryx 21 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1017/S0030605300020457.

- Bryner, Jeanna (6 November 2014). "In Photos: The Famous Flightless Dodo Bird". livescience.com. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Cheke, Anthony S. (2004). "The Dodo's last island" (PDF). Royal Society of Arts and Sciences of Mauritius. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Cheke, A. S. (2006). "Establishing extinction dates – the curious case of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the Red Hen Aphanapteryx bonasia". Ibis 148: 155–158. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00478.x.

- Cheke, Anthony S.; Hume, Julian Pender (2008). Lost Land of the Dodo: an Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion & Rodrigues. New Haven and London: T. & A. D. Poyser. ISBN 978-0-7136-6544-4.

- Christie's (2009). "Dutch School, 17th Century; A dodo". Christies.com. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Choi, Charles Q. (6 November 2014). "Dodo Bird Skeleton Reveals Long-Lost Secrets in 3D Scan". livescience.com. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Clark, G. (April 1866). "Account of the late Discovery of Dodos' Remains in the Island of Mauritius". Ibis 8 (2): 141–146. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1866.tb06082.x.

- Cocks, T. (2006). "Natural disaster may have killed dodos". Reuters. Retrieved 30 August 2006.

- Dissanayake, R. (2004). "What did the dodo look like?" (PDF). The Biologist (Society of Biology) 51 (3): 165–168. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- Fryer, J. (14 September 2002). "Bringing the dodo back to life". BBC News (London). Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- Fuller, Errol (2001). Extinct Birds (revised ed.). New York: Comstock. ISBN 978-0-8014-3954-4.

- Fuller, Errol (2002). Dodo – From Extinction To Icon. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-714572-0.

- Fuller, Errol (2003). The Dodo – Extinction In Paradise (first ed.). USA: Bunker Hill Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-59373-002-4.

- Gillespie, Rosemary G.; Clague, David A. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islands. Berkeley (US): University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25649-1.

- Hakluyt, Richard (2013) [1812]. A Selection of Curious, Rare and Early Voyages and Histories of Interesting Discoveries. London (UK): R.H. Evans and R. Priestley.

- Hakluyt, Richard (2004). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of The English Nation, Volume 10, Asia Part III. The Project Gutenberg EBook.

- Herhey, D. R. (2004). "Plant Science Bulletin, Volume 50, Issue 4". Botany.org. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Hill, A. W. (1941). "The genus Calvaria, with an account of the stony endocarp and germination of the seed, and description of the new species". Annals of Botany 5: 587–606.

- Hume, J. P.; Steel, L. (2013). "Fight club: A unique weapon in the wing of the solitaire, Pezophaps solitaria (Aves: Columbidae), an extinct flightless bird from Rodrigues, Mascarene Islands". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society: n/a. doi:10.1111/bij.12087.

- Hume, J. P. (2003). "The journal of the flagship Gelderland – dodo and other birds on Mauritius 1601". Archives of Natural History 30 (1): 13–27. doi:10.3366/anh.2003.30.1.13.

- Hume, Julian Pender; Martill, David M.; Dewdney, Christopher (June 2004). "Palaeobiology: Dutch diaries and the demise of the dodo". Nature 429 (6992): 1 p following 621. Bibcode:2004Natur.429.....H. doi:10.1038/nature02688. PMID 15190921.

- Hume, Julian Pender (2005). "Contrasting taphofacies in ocean island settings: the fossil record of Mascarene vertebrates". Proceedings of the International Symposium "Insular Vertebrate Evolution: the Palaeontological Approach". Monografies de la Societat d'Història Natural de les Balears 12: 129–144.

- Hume, J. P. (2006). "The History of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the Penguin of Mauritius" (PDF). Historical Biology 18 (2): 69–93. doi:10.1080/08912960600639400. ISSN 0891-2963.

- Hume, Julian Pender; Datta, Anna; Martill, David M. (2006). "Unpublished drawings of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and notes on Dodo skin relics" (PDF). Bull. B. O. C. 126A: 49–54. ISSN 0007-1595. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- Hume, J. P.; Cheke, A. S. (2004). "The white dodo of Réunion Island: Unravelling a scientific and historical myth" (PDF). Archives of Natural History 31 (1): 57–79. doi:10.3366/anh.2004.31.1.57.

- Hume, Julian Pender; Cheke, Anthony S.; McOran-Campbell, A. (2009). "How Owen 'stole' the Dodo: Academic rivalry and disputed rights to a newly-discovered subfossil deposit in nineteenth century Mauritius" (PDF). Historical Biology 21 (1–2): 33–49. doi:10.1080/08912960903101868.

- Hume, J. P. (2012). "The Dodo: From extinction to the fossil record". Geology Today 28 (4): 147–151. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2451.2012.00843.x.

- Hume, Julian Pender; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. London: A & C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-5725-1.

- Iwanow, A. (October 1958). "An Indian picture of the Dodo". Journal of Ornithology 99 (4): 438–440. doi:10.1007/BF01671614.

- Janoo, A. (April–June 2005). "Discovery of Isolated Dodo Bones [Raphus cucullatus (L.), Aves, Columbiformes] from Mauritius Cave Shelters Highlights Human Predation, with a Comment on the Status of the Family Raphidae Wetmore, 1930". Annales de Paléontologie 91 (2): 167–180. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2004.12.002.

- Jamieson, Alastair (22 June 2009). "Uncovered: 350-year-old picture of Dodo before it was extinct". The Daily Telegraph (London). Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Kennedy, M. (21 February 2011). "Half a Dodo found in museum drawer". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Kitchener, A. C. (June 1993). "On the external appearance of the dodo, Raphus cucullatus (L, 1758)". Archives of Natural History 20 (2): 279–301. doi:10.3366/anh.1993.20.2.279.

- Kitchener, Andrew C. (August 1993). "Justice at last for the dodo". New Scientist: 24.

- Kuntner, M.; Agnarsson, I. (May 2011). "Biogeography and diversification of hermit spiders on Indian Ocean islands (Nephilidae: Nephilengys)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 59 (2): 477–488. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.02.002. PMID 21316478.

- Laing, A. (27 August 2010). "Last surviving Dodo egg could be tested for authenticity". The Daily Telegraph (London).

- Livezey, B. C. (1993). "An Ecomorphological Review of the Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) and Solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria), Flightless Columbiformes of the Mascarene Islands". Journal of Zoology 230 (2): 247–292. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1993.tb02686.x.

- de Lozoya, A. V. (2003). "An unnoticed painting of a white Dodo". Journal of the History of Collections 15 (2): 201–210. doi:10.1093/jhc/15.2.201.

- Louchart, A.; Mourer-Chauviré, C. C. C. (April 2011). "The dodo was not so slim: Leg dimensions and scaling to body mass". Naturwissenschaften 98 (4): 357–358; discussion 358–360. Bibcode:2011NW.....98..357L. doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0771-6. PMID 21380621.

- Lydekker, R. (1891). Catalogue of the Fossil Birds in the British Museum (Natural History). Taylor & Francis. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.8301. OCLC 4170867.

- MacGregor, A. (2001). "The Ashmolean as a museum of natural history, 1683 1860". Journal of the History of Collections 13 (2): 125–144. doi:10.1093/jhc/13.2.125.

- Macmillan, A. (2000). Mauritius Illustrated: Historical and Descriptive, Commercial and Industrial Facts, Figures, & Resources. New Dheli: Asian Educational Services. p. 83. ISBN 978-81-206-1508-3. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Mason, A. S. (1992). George Edwards: The Bedell and His Birds. London: Royal College of Physicians of London. ISBN 978-1-873240-48-9. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Mauritius-Holidays-Discovery.Com. "Mauritius Natural History Museum, Port Louis". Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Mayell, H. (28 February 2002). "Extinct Dodo Related to Pigeons, DNA Shows". National Geographic News. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- McNab, B. K. (1999). "On the Comparative Ecological and Evolutionary Significance of Total and Mass-Specific Rates of Metabolism". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 72 (5): 642–644. doi:10.1086/316701. JSTOR 10.1086/316701. PMID 10521332.

- Meijer, H. J. M.; Gill, A.; de Louw, P. G. B.; van den Hoek Ostende, L. W.; Hume, J. P.; Rijsdijk, K. F. (2012). "Dodo remains from an in situ context from Mare aux Songes, Mauritius". Naturwissenschaften 99 (3): 177–184. Bibcode:2012NW.....99..177M. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0882-8. PMID 22282037.

- Milne-Edwards, A. (1869). "Researches into the zoological affinities of the bird recently described by Herr von Frauenfeld under the name of Aphanapteryx imperialis". Ibis 11 (3): 256–275. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1869.tb06880.x.

- Mourer-Chauviré, C.; Moutou, F. (1987). "Découverte d'une forme récemment éteinte d'ibis endémique insulaire de l'île de la Réunion Borbonibis latipes n. gen. n. sp" [Discovery of a recently extinct island endemic ibis from Réunion: Borbonibis latipes n. gen. n. sp.]. Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences. Série D (in French) 305 (5): 419–423.

- Mourer-Chauviré, C. C.; Bour, R.; Ribes, S. (1995). "Was the solitaire of Réunion an ibis?". Nature 373 (6515): 568. Bibcode:1995Natur.373..568M. doi:10.1038/373568a0.

- Mourer-Chauviré, C. C.; Bour, R.; Ribes, S. (1995-06-01). "Position systématique du Solitaire de la Réunion: nouvelle interprétation basée sur les restes fossiles et les récits des anciens voyageurs". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences ((SER2,T320,N11)).

- Newton, A. (January 1865). "2. On Some Recently Discovered Bones of the Largest Known Species of Dodo (Didus Nazarenus, Bartlett)". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 33 (1): 199–201. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1865.tb02320.x.

- Newton, E.; Gadow, H. (1893). "IX. On additional bones of the Dodo and other extinct birds of Mauritius obtained by Mr. Theodore Sauzier". The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 13 (7): 281–302. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1893.tb00001.x.

- Owen, R. (January 1867). "On the Osteology of the Dodo (Didus ineptus, Linn.)". The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 6 (2): 49–85. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1867.tb00571.x.

- Ovenell, R. F. (June 1992). "The Tradescant Dodo". Archives of Natural History 19 (2): 145–152. doi:10.3366/anh.1992.19.2.145.

- Parish, Jolyon C. (2013). The Dodo and the Solitaire: A Natural History. Bloomington (US): Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00099-6.

- Pereira, S. L.; Johnson, K. P.; Clayton, D. H.; Baker, A. J. (2007). "Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences support a Cretaceous origin of Columbiformes and a dispersal-driven radiation in the Paleogene". Systematic Biology 56 (4): 656–672. doi:10.1080/10635150701549672. PMID 17661233.

- Ravilious, K. (2007). "Dodo Skeleton Found on Island, May Yield Extinct Bird's DNA". National Geographic.

- Reinhardt, Johannes Theodor (1842–1843). "Nøjere oplysning om det i Kjøbenhavn fundne Drontehoved". Nat. Tidssk. Krøyer. IV.: 71–72. 2.

- Richards, Alexandra (2012). Mauritius, Rodrigues, Réunion (8 ed.). Chalfont St. Peter, Bucks, UK: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-410-5.

- Rijsdijk, K. F.; Hume, J. P.; Bunnik, F.; Florens, F. B. V.; Baider, C.; Shapiro, B.; van der Plicht, H.; Janoo, A.; et al. (January 2009). "Mid-Holocene vertebrate bone Concentration-Lagerstätte on oceanic island Mauritius provides a window into the ecosystem of the dodo (Raphus cucullatus)". Quaternary Science Reviews 28 (1–2): 14–24. Bibcode:2009QSRv...28...14R. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.09.018. (subscription required (help)).

- Rijsdijk, K. F.; Zinke, J.; de Louw, P. G. B.; Hume, J. P.; Van Der Plicht, H.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Meijer, H. J. M.; Vonhof, H. B.; et al. (2011). "Mid-Holocene (4200 kyr BP) mass mortalities in Mauritius (Mascarenes): Insular vertebrates resilient to climatic extremes but vulnerable to human impact". The Holocene 21 (8): 1179–1194. doi:10.1177/0959683611405236. (subscription required (help)).

- Roberts, D. L.; Solow, A. R. (November 2003). "Flightless birds: When did the dodo become extinct?". Nature 426 (6964): 245. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..245R. doi:10.1038/426245a. PMID 14628039.

- Rothschild, Walter (1907). Extinct Birds. London: Hutchinson & Co.

- Rothschild, W. (1919). "On one of the four original pictures from life of the Réunion or white Dodo" (PDF). The Ibis 36 (2): 78–79. doi:10.2307/4073093. JSTOR 4073093.

- Schaper, M. T.; Goupille, M. (2003). "Fostering enterprise development in the Indian Ocean: The case of Mauritius". Small Enterprise Research 11 (2): 93. doi:10.5172/ser.11.2.93.

- Shapiro, B.; Sibthorpe, D.; Rambaut, A.; Austin, J.; Wragg, G. M.; Bininda-Emonds, O. R. P.; Lee, P. L. M.; Cooper, A. (2002). "Flight of the Dodo" (PDF). Science 295 (5560): 1683. doi:10.1126/science.295.5560.1683. PMID 11872833. Supplementary information

- Staub, France (1996). "Dodo and solitaires, myths and reality". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Arts & Sciences of Mauritius 6: 89–122.

- Storer, R. W. (1970). "Independent Evolution of the Dodo and the Solitaire". The Auk 87 (2): 369–370. doi:10.2307/4083934. JSTOR 4083934.