Dinah

In the Hebrew Bible, Dinah (/ˈdaɪnə/; Hebrew: דִּינָה, Modern Dina, Tiberian Dînā ; "judged; vindicated") was the daughter of Jacob, one of the patriarchs of the Israelites, and Leah, his first wife. The episode of her violation by Shechem, son of a Canaanite or Hivite prince, and the subsequent vengeance of her brothers Simeon and Levi, commonly referred to as the rape of Dinah, is told in Genesis 34.[1]

Dinah in Genesis

Dinah, the daughter of Leah and Jacob, went out to visit the women of Shechem, where her people had made camp and where her father Jacob had purchased the land where he had pitched his tent. Shechem (the son of Hamor, the prince of the land) "took her and lay with her and humbled her. And his soul was drawn to Dinah ... he loved the maiden and spoke tenderly to her", and Shechem asked his father to obtain Dinah for him, to be his wife.

Hamor came to Jacob and asked for Dinah for his son: "Make marriages with us; give your daughters to us, and take our daughters for yourselves. You shall dwell with us; and the land shall be open to you." Shechem offered Jacob and his sons any bride-price they named. But "the sons of Jacob answered Shechem and his father Hamor deceitfully, because he had defiled their sister Dinah"; they said they would accept the offer if the men of the city agreed to be circumcised.

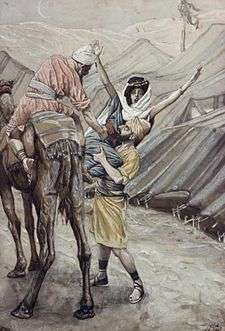

So the men of Shechem were deceived, and were circumcised; and "on the third day, when they were sore, two of the sons of Jacob and Leah, Simeon and Levi, Dinah's brothers, took their swords and came upon the city unawares, and killed all the males. They slew Hamor and his son Shechem with the sword, and took Dinah out of Shechem's house, and went away." And the sons of Jacob plundered whatever was in the city and in the field, "all their wealth, all their little ones and their wives, all that was in the houses."

"Then Jacob said to Simeon and Levi, 'You have brought trouble on me by making me odious to the inhabitants of the land, the Canaanites and the Perizzites; my numbers are few, and if they gather themselves against me and attack me, I shall be destroyed, both I and my household.' But they said, 'Should he treat our sister as a harlot?'" (Genesis 34:31).

Origin of Genesis 34

This portion of the Book of Genesis deals primarily with the family of Abraham and his descendants, including Dinah, her father Jacob, and her brothers. The traditional view is that Moses wrote Genesis as well as almost all the rest of the Torah, doubtlessly using varied sources but synthesizing all of them together to give the Hebrews a written history of their ancestors. This view—which has been held for the past several thousand years, although it is not explicitly mentioned in either the Hebrew or the Christian Bible—holds that Moses included this story primarily because it happened and he viewed it as significant. It foreshadows later happenings and prophecies further along in Genesis and the Torah dealing with the two violent brothers.

Source-critical scholars speculate that Genesis combines separate literary strands, with different values and concerns, and does not pre-date the 1st millennium BC as a unified account.[2] Within Genesis 34 itself, they suggest two layers of narrative : an older account ascribing the killing of Shechem to Simeon and Levi alone, and a later addition (verses 27 to 29) involving all the sons of Jacob.[3] Kirsch argues that the narrative combines a Yahwist narrator describing a rape, and an Elohist speaker describing a seduction.[4]

On the other hand, another critical scholar, Alexander Rofé, assumes that the earlier authors would not have considered rape to be defilement in and of itself, and posits that the verb describing Dinah as "defiled" was added later (elsewhere in the Bible, only married or betrothed women are "defiled" by rape). He instead says that such a description reflected a "late, post-exilic notion that the idolatrous gentiles are impure [and supports] the prohibition of intermarriage and intercourse with them." Such a supposed preoccupation with ethnic purity must therefore indicate a late date for Genesis in the 5th or 4th centuries BC, when the restored Jewish community in Jerusalem was similarly preoccupied with anti-Samaritan polemics.[5] In the extant (currently existing) version, it is clear that rape took place; the verb translated as "humbled" or "violated" in chapter 34 can also mean "subdued".[5]

Dinah in rabbinic literature

Midrashic literature contains a series of proposed explanations of the Bible by rabbis. It provides further hypotheses of the story of Dinah, suggesting answers to questions such as her offspring from Shechem and links to later incidents and characters.

One midrash states that Dinah was conceived as a male in Leah's womb but miraculously changed to a female, lest Leah be associated with more of the Israelite tribes than Rachel. (Berkahot 60a)

Another midrash implicates Jacob in Dinah's misfortune: when he went to meet Esau, he locked Dinah in a box, for fear that Esau would wish to marry her,[6] but God rebuked him in these words: "If thou hadst married off thy daughter in time she would not have been tempted to sin, and might, moreover, have exerted a beneficial influence upon her husband" (Gen. R. lxxx.). Her brother Simeon promised to find a husband for her, but she did not wish to leave Shechem, fearing that, after her disgrace, no one would take her to wife (Gen. R. l.c.).[6] However, she was later married to Job (Bava Batra 15b; Gen. R. l.c.).[6] When she died, Simeon buried her in the land of Canaan. She is therefore referred to as "the Canaanitish woman" (Gen. 46:10).[6] Shaul/Asenath (ib.) was her son/daughter by Shechem (Gen. R. l.c.).[6][7]

Early Christian commentators such as Jerome likewise assign some of the responsibility to Dinah, in venturing out to visit the women of Shechem. This story was used to demonstrate the danger to women in the public sphere as contrasted with the relative security of remaining in private.[8]

Simeon and Levi

On his deathbed, their father Jacob curses Simeon and Levi's anger (Genesis 49). Their tribal portions in the land of Israel are dispersed so that they would not be able to regroup and fight arbitrarily. According to the Midrash, Simeon and Levi were only 14 and 13 years old, respectively, at the time of the rape of Dinah. They possessed great moral zealousness (later, in the episode of the Golden Calf, the Tribe of Levi would demonstrate their absolute commitment to Moses' leadership by killing all the people involved in idol worship), but their anger was misdirected here.

One midrash told how Jacob later tried to restrain their hot tempers by dividing their portions in the land of Israel, and neither had lands of their own. Therefore, Dinah's son by Shechem was counted among Simeon's progeny and received a portion of land in Israel, Dinah herself being "the Canaanite woman" mentioned among those who went down into Egypt with Jacob and his sons (Gen. 46:10).[6] When she died, Simeon buried her in the land of Canaan. (According to another tradition, her child from her rape by Shechem was Asenath, the wife of Joseph, and she herself later married the prophet Job (Bava Batra 15b; Gen. R. l.c.).[6]) The Tribe of Simeon received land within the territory of Judah and served as itinerant teachers in Israel, traveling from place to place to earn a living.

In the Hebrew Bible, the tribe of Levi received a few Cities of Refuge spread out over Israel, and relied for their sustenance on the priestly gifts that the Children of Israel gave them.

In medieval rabbinic literature, there were efforts to justify the killing, not merely of Shechem and Hamor, but of all the townsmen. Maimonides argued that the killing was understandable because the townsmen had failed to uphold the seventh Noachide law (denim) to establish a criminal justice system. However, Nachmanides disagreed, partly because he viewed the seventh law as a positive commandment that was not punishable by death. Instead, Nachmanides said that the townsmen presumably violated other Noachide laws, such as idolatry or sexual immorality. Later, the Maharal reframed the issue—not as sin, but rather as a war. That is, he argued that Simeon and Levi acted lawfully insofar as they carried out a military operation as an act of vengeance or retribution for the rape of Dinah.[9]

Travel to Egypt

When Jacob's family prepares to descend to Egypt Genesis 46:8-27, the Torah lists the 70 family members who went down together. Simeon's children include "Saul, the son of the Canaanite woman."[10] The medieval French rabbi Rashi hypothesized that this Saul was Dinah's son by Shechem.[10] He suggests that after the brothers killed all the men in the city, including Shechem and his father, Dinah refused to leave the palace unless Simeon agreed to marry her[10] and remove her shame (according to Nachmanides, she only lived in his house and did not have sex with him). Therefore, Dinah's son is counted among Simeon's progeny, and he received a portion of land in Israel in the time of Joshua. The list of the names of the families of Israel in Egypt is repeated in Exodus 6:14-25.

In culture

Symbol of black womanhood

In 19th century America, "Dinah" became a generic name for an enslaved African woman.[11] At the 1850 Woman's Rights Convention in New York, a speech by Sojourner Truth was reported on in the New York Herald, which used the name "Dinah" to symbolize black womanhood as represented by Truth:

In a convention where sex and color are mingled together in the common rights of humanity, Dinah, and Burleigh, and Lucretia, and Frederick Douglas, are all spiritually of one color and one sex, and all on a perfect footing of reciprocity. Most assuredly, Dinah was well posted up on the rights of woman, and with something of the ardor and the odor of her native Africa, she contended for her right to vote, to hold office, to practice medicine and the law, and to wear the breeches with the best white man that walks upon God's earth.[11]

Lizzie McCloud, a slave on a Tennessee plantation during the American Civil War, recalled that Union soldiers called all enslaved women "Dinah". Describing her fear when the Union army arrived, she said: "We was so scared we run under the house and the Yankees called 'Come out Dinah' (didn't call none of us anything but Dinah). They said 'Dinah, we're fightin' to free you and get you out from under bondage'."[12] After the end of the war in 1865 The New York Times exhorted the newly liberated slaves to demonstrate that they had the moral values to use their freedom effectively, using the names "Sambo" and "Dinah" to represent male and female former slaves: "You are free Sambo, but you must work. Be virtuous too, oh Dinah!"[13]

The name Dinah was subsequently used for dolls and other images of black women.[14]

In literature

The short story "The Rape of Dina" by Gabriel Krauze is a true story about a murder on the South Kilburn housing estate in London. In Gabriel Krauze's story the rape of Dinah by the prince of Shechem and the revenge which her brothers take, is compared to the act of revenge that takes place in South Kilburn Estate.[15]

The novel The Red Tent by Anita Diamant is a fictional autobiography of the biblical Dinah. In Diamant's version, Dinah falls in love with Shalem, the Canaanite prince, and goes to bed with him in preparation for marriage. Simon and Levi, Jacob's sons, instigate the discord between Jacob and the men of the King of Shechem out of fear for their own prosperity, even though Dinah tells them the truth.

See also

References

- ↑ Genesis 34

- ↑ "Table D Source Analysis: Revisions and Alternatives". Reading the Old Testament. Archived from the original on 17 February 2001.

- ↑ Van Seters, John (2001). "The Silence of Dinah (Genesis 34)". In Jean-Daniel Macchi and Thomas Römer. Jacob: Commentaire à Plusieurs Voix de Gen. 25–36. Mélanges Offerts à Albert de Pury. Geneva: Labor et Fides. pp. 239–247. ISBN 2-8309-0987-9. OCLC 248784525.

- ↑ Kirsch, Jonathan. Harlot by the Side of the Road, Random House, 2009.

- 1 2 Rofé, Alexander (2005). "Defilement of Virgins in Biblical Law and the Case of Dinah (Genesis 34)" (PDF). Biblica 86 (3): 369–375. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Dinah", JewishEncyclopedia.com

- ↑ "Asenath", JewishEncyclopedia.com

- ↑ Shemesh, Yael. "Review of Joy A. Schroeder's Dinah’s Lament: The Biblical Legacy of Sexual Violence in Christian Interpretation", Review of Biblical Literature, July 2008, Society of Biblical Literature.

- ↑ Blau, Yitzkhak (2006). "BIBLICAL NARRATIVES AND THE STATUS OF ENEMY CIVILIANS IN WARTIME". Tradition 39:4.

- 1 2 3 Bereishit - Chapter 46 - Genesis at chabad.org

- 1 2 Footnote 3 to "Women's Rights Convention", The New York Herald, October 26, 1850; U.S. Women's History Workshop.

- ↑ Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves, The Federal Writers' Project, 1936-1938. Library of Congress, 1941.

- ↑ Gutmann, Herbert. "Persistent Myths about the Afro-American Family" in The Slavery Reader, Psychology Press, 2003, p.263.

- ↑ Husfloen, Kyle. Black Americana, Krause Publications, 2005, p.64.

- ↑ "The Rape of Dina" at vice.com

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906.

Further reading

- Schroeder, Joy A. Dinah's Lament: The Biblical Legacy of Sexual Violence in Christian Interpretation. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2007. ISBN 978-0800638436

- Shemesh, Yael (August 2007). "Rape is Rape is Rape: The story of Dinah and Shechem (Genesis 34)". Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 119 (1): 2–21. doi:10.1515/ZAW.2007.002. ISSN 0044-2526.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dinah. |

External links

- Dinah's Abduction from a Jewish perspective at Chabad.org

- Blyth, C. (2008). "Redeemed by His Love? The Characterization of Shechem in Genesis 34". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 33: 3. doi:10.1177/0309089208094457.

| ||||||||||||||||||