Random number generation

A random number generator (RNG) is a computational or physical device designed to generate a sequence of numbers or symbols that can not be reasonably predicted better than by a random chance.

Various applications of randomness have led to the development of several different methods for generating random data, of which some have existed since ancient times, including dice, coin flipping, the shuffling of playing cards, the use of yarrow stalks (for divination) in the I Ching, and many other techniques. Because of the mechanical nature of these techniques, generating large numbers of sufficiently random numbers (important in statistics) required a lot of work and/or time. Thus, results would sometimes be collected and distributed as random number tables. Nowadays, after the advent of computational random-number generators, a growing number of government-run lotteries and lottery games have started using RNGs instead of more traditional drawing-methods. RNGs are also used to determine the odds of modern slot machines.[1]

Several computational methods for random number generation exist. Many fall short of the goal of true randomness, although they may meet, with varying success, some of the statistical tests for randomness intended to measure how unpredictable their results are (that is, to what degree their patterns are discernible). However, carefully designed cryptographically secure computationally based methods of generating random numbers also exist, such as those based on the Yarrow algorithm, the Fortuna (PRNG), and others.

Practical applications and uses

Random number generators have applications in gambling, statistical sampling, computer simulation, cryptography, completely randomized design, and other areas where producing an unpredictable result is desirable. Generally, in applications having unpredictability as the paramount, such as in security applications, hardware generators are generally preferred over pseudo-random algorithms, where feasible.

Random number generators are very useful in developing Monte Carlo-method simulations, as debugging is facilitated by the ability to run the same sequence of random numbers again by starting from the same random seed. They are also used in cryptography – so long as the seed is secret. Sender and receiver can generate the same set of numbers automatically to use as keys.

The generation of pseudo-random numbers is an important and common task in computer programming. While cryptography and certain numerical algorithms require a very high degree of apparent randomness, many other operations only need a modest amount of unpredictability. Some simple examples might be presenting a user with a "Random Quote of the Day", or determining which way a computer-controlled adversary might move in a computer game. Weaker forms of randomness are used in hash algorithms and in creating amortized searching and sorting algorithms.

Some applications which appear at first sight to be suitable for randomization are in fact not quite so simple. For instance, a system that "randomly" selects music tracks for a background music system must only appear random, and may even have ways to control the selection of music: a true random system would have no restriction on the same item appearing two or three times in succession.

"True" vs. pseudo-random numbers

There are two principal methods used to generate random numbers. The first method measures some physical phenomenon that is expected to be random and then compensates for possible biases in the measurement process. Example sources include measuring atmospheric noise, thermal noise, and other external electromagnetic and quantum phenomena. For example, cosmic background radiation or radioactive decay as measured over short timescales represent sources of natural entropy.

The speed at which entropy can be harvested from natural sources is dependent on the underlying physical phenomena being measured. Thus, sources of naturally occurring "true" entropy are said to be blocking – they are rate-limited until enough entropy is harvested to meet the demand. On some Unix-like systems, including most Linux distributions, the pseudo device file /dev/random will block until sufficient entropy is harvested from the environment.[2] Due to this blocking behavior, large bulk reads from /dev/random, such as filling a hard disk drive with random bits, can often be slow on systems that use this type of entropy source.

The second method uses computational algorithms that can produce long sequences of apparently random results, which are in fact completely determined by a shorter initial value, known as a seed value or key. As a result, the entire seemingly random sequence can be reproduced if the seed value is known. This type of random number generator is often called a pseudorandom number generator. This type of generator typically does not rely on sources of naturally occurring entropy, though it may be periodically seeded by natural sources. This generator type is non-blocking, so they are not rate-limited by an external event, making large bulk reads a possibility.

Some systems take a hybrid approach, providing randomness harvested from natural sources when available, and falling back to periodically re-seeded software-based cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generators (CSPRNGs). The fallback occurs when the desired read rate of randomness exceeds the ability of the natural harvesting approach to keep up with the demand. This approach avoids the rate-limited blocking behavior of random number generators based on slower and purely environmental methods.

While a pseudorandom number generator based solely on deterministic logic can never be regarded as a "true" random number source in the purest sense of the word, in practice they are generally sufficient even for demanding security critical applications. Indeed, carefully designed and implemented pseudo-random number generators can be certified for security-critical cryptographic purposes, as is the case with the yarrow algorithm and fortuna. The former is the basis of the /dev/random source of entropy on FreeBSD, AIX, OS X, NetBSD and others. OpenBSD also uses a pseudo-random number algorithm based on ChaCha20 known as arc4random.[3]

Generation methods

Physical methods

The earliest methods for generating random numbers, such as dice, coin flipping and roulette wheels, are still used today, mainly in games and gambling as they tend to be too slow for most applications in statistics and cryptography.

A physical random number generator can be based on an essentially random atomic or subatomic physical phenomenon whose unpredictability can be traced to the laws of quantum mechanics. Sources of entropy include radioactive decay, thermal noise, shot noise, avalanche noise in Zener diodes, clock drift, the timing of actual movements of a hard disk read/write head, and radio noise. However, physical phenomena and tools used to measure them generally feature asymmetries and systematic biases that make their outcomes not uniformly random. A randomness extractor, such as a cryptographic hash function, can be used to approach a uniform distribution of bits from a non-uniformly random source, though at a lower bit rate.

Various imaginative ways of collecting this entropic information have been devised. One technique is to run a hash function against a frame of a video stream from an unpredictable source. Lavarand used this technique with images of a number of lava lamps. HotBits measures radioactive decay with Geiger–Muller tubes,[4] while Random.org uses variations in the amplitude of atmospheric noise recorded with a normal radio.

Another common entropy source is the behavior of human users of the system. While people are not considered good randomness generators upon request, they generate random behavior quite well in the context of playing mixed strategy games.[5] Some security-related computer software requires the user to make a lengthy series of mouse movements or keyboard inputs to create sufficient entropy needed to generate random keys or to initialize pseudorandom number generators.[6]

Computational methods

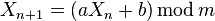

Most computer generated random numbers use Pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) which are algorithms that can automatically create long runs of numbers with good random properties but eventually the sequence repeats (or the memory usage grows without bound).This kind of random numbers are fine in many situations but are not as random as coin tosses and dice rolls.[7] The series of values generated by such algorithms is generally determined by a fixed number called a seed. One of the most common PRNG is the linear congruential generator, which uses the recurrence

to generate numbers, where a, b and m are large integers, and  is the next in X as a series of pseudo-random numbers. The maximum number of numbers the formula can produce is the modulus, m. To avoid certain non-random properties of a single linear congruential generator, several such random number generators with slightly different values of the multiplier coefficient, a, can be used in parallel, with a "master" random number generator that selects from among the several different generators.

is the next in X as a series of pseudo-random numbers. The maximum number of numbers the formula can produce is the modulus, m. To avoid certain non-random properties of a single linear congruential generator, several such random number generators with slightly different values of the multiplier coefficient, a, can be used in parallel, with a "master" random number generator that selects from among the several different generators.

A simple pen-and-paper method for generating random numbers is the so-called middle square method suggested by John von Neumann. While simple to implement, its output is of poor quality. It has a very short period and severe weaknesses, such as the output sequence almost always converging to zero.

Most computer programming languages include functions or library routines that provide random number generators. They are often designed to provide a random byte or word, or a floating point number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1.

The quality i.e. randomness of such library functions varies widely from completely predictable output, to cryptographically secure. The default random number generator in many languages, including Python, Ruby, R, IDL and PHP is based on the Mersenne Twister algorithm and is not sufficient for cryptography purposes, as is explicitly stated in the language documentation. Such library functions often have poor statistical properties and some will repeat patterns after only tens of thousands of trials. They are often initialized using a computer's real time clock as the seed, since such a clock generally measures in milliseconds, far beyond the person's precision. These functions may provide enough randomness for certain tasks (for example video games) but are unsuitable where high-quality randomness is required, such as in cryptography applications, statistics or numerical analysis.

Much higher quality random number sources are available on most operating systems; for example /dev/random on various BSD flavors, Linux, Mac OS X, IRIX, and Solaris, or CryptGenRandom for Microsoft Windows. Most programming languages, including those mentioned above, provide a means to access these higher quality sources.

Generation from a probability distribution

There are a couple of methods to generate a random number based on a probability density function. These methods involve transforming a uniform random number in some way. Because of this, these methods work equally well in generating both pseudo-random and true random numbers. One method, called the inversion method, involves integrating up to an area greater than or equal to the random number (which should be generated between 0 and 1 for proper distributions). A second method, called the acceptance-rejection method, involves choosing an x and y value and testing whether the function of x is greater than the y value. If it is, the x value is accepted. Otherwise, the x value is rejected and the algorithm tries again.[8][9]

By humans

Random number generation may also be performed by humans, in the form of collecting various inputs from end users and using them as a randomization source. However, most studies find that human subjects have some degree of non randomness when attempting to produce a random sequence of e.g. digits or letters. They may alternate too much between choices when compared to a good random generator;[10] thus, this approach is not widely used.

Post-processing and statistical checks

Even given a source of plausible random numbers (perhaps from a quantum mechanically based hardware generator), obtaining numbers which are completely unbiased takes care. In addition, behavior of these generators often changes with temperature, power supply voltage, the age of the device, or other outside interference. And a software bug in a pseudo-random number routine, or a hardware bug in the hardware it runs on, may be similarly difficult to detect.

Generated random numbers are sometimes subjected to statistical tests before use to ensure that the underlying source is still working, and then post-processed to improve their statistical properties. An example would be the TRNG9803[11] hardware random number generator, which uses an entropy measurement as a hardware test, and then post-processes the random sequence with a shift register stream cipher. It is generally hard to use statistical tests to validate the generated random numbers. Wang and Nicol[12] proposed a distance-based statistical testing technique that is used to identify the weaknesses of several random generators.

Other considerations

Random numbers uniformly distributed between 0 and 1 can be used to generate random numbers of any desired distribution by passing them through the inverse cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the desired distribution(see Inverse_transform_sampling). Inverse CDFs are also called quantile functions. To generate a pair of statistically independent standard normally distributed random numbers (x, y), one may first generate the polar coordinates (r, θ), where r~χ22 and θ~UNIFORM(0,2π) (see Box–Muller transform).

Some 0 to 1 RNGs include 0 but exclude 1, while others include or exclude both.

The outputs of multiple independent RNGs can be combined (for example, using a bit-wise XOR operation) to provide a combined RNG at least as good as the best RNG used. This is referred to as software whitening.

Computational and hardware random number generators are sometimes combined to reflect the benefits of both kinds. Computational random number generators can typically generate pseudo-random numbers much faster than physical generators, while physical generators can generate "true randomness."

Low-discrepancy sequences as an alternative

Some computations making use of a random number generator can be summarized as the computation of a total or average value, such as the computation of integrals by the Monte Carlo method. For such problems, it may be possible to find a more accurate solution by the use of so-called low-discrepancy sequences, also called quasirandom numbers. Such sequences have a definite pattern that fills in gaps evenly, qualitatively speaking; a truly random sequence may, and usually does, leave larger gaps.

Activities and demonstrations

The following sites make available Random Number samples:

- The SOCR resource pages contain a number of hands-on interactive activities and demonstrations of random number generation using Java applets.

- The Quantum Optics Group at the ANU generates random numbers sourced from quantum vacuum. You can download a sample of random numbers by visiting their quantum random number generator research page.

- Random.Org makes available random numbers that are sourced from the randomness of atmospheric noise. Visit their page to obtain a sample.

- The Quantum Random Bit Generator Service at the Ruđer Bošković Institute harvests randomness from the quantum process of photonic emission in semiconductors. They supply a variety of ways of fetching the data, including libraries for several programming languages.

Backdoors

Since much cryptography depends on a cryptographically secure random number generator for key and cryptographic nonce generation, if a random number generator can be made predictable, it can be used as backdoor by an attacker to break the encryption.

The NSA is reported to have inserted a backdoor into the NIST certified cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator Dual_EC_DRBG. If for example an SSL connection is created using this random number generator, then according to Matthew Green it would allow NSA to determine the state of the random number generator, and thereby eventually be able to read all data sent over the SSL connection.[13] Even though it was apparent that Dual_EC_DRBG was a very poor and possibly backdoored pseudorandom number generator long before the NSA backdoor was confirmed in 2013, it had seen significant usage in practice until 2013, for example by the prominent security company RSA Security.[14] There have subsequently been accusations that RSA Security knowingly inserted a NSA backdoor into its products, possibly as part of the Bullrun program. RSA has denied knowingly inserting a backdoor into its products.[15]

It has also been theorized that hardware RNGs could be secretly modified to have less entropy than stated, which would make encryption using the hardware RNG susceptible to attack. One such method which has been published works by modifying the dopant mask of the chip, which would be undetectable to optical reverse-engineering.[16] For example, for random number generation in Linux, it is seen as unacceptable to use Intel's RdRand hardware RNG without mixing in the RdRand output with other sources of entropy to counteract any backdoors in the hardware RNG, especially after the revelation of the NSA Bullrun program.[17][18]

In popular culture

The process of random number generation in games, especially in roguelike games, is often referred to as being controlled by a "Random Number God" or "RN-Jesus". The term was originally coined by players of the games Angband and NetHack,[19] and also references the belief that certain actions can either appease or anger the "God", leading to number generation seemingly skewed for or against the player.

See also

References

- ↑ "Introduction to Slot Machines". slotsvariations.com. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- ↑ – Linux Programmer's Manual – Special Files

- ↑ deraadt, ed. (2014-07-21). "libc/crypt/arc4random.c". BSD Cross Reference, OpenBSD src/lib/. Retrieved 2015-01-13.

ChaCha based random number generator for OpenBSD.

- ↑ Walker, John. "HotBits: Genuine Random Numbers". Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- ↑ Halprin, Ran; Naor, Moni. "Games for Extracting Randomness" (PDF). Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, Weizmann Institute of Science. Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- ↑ TrueCrypt Foundation. "TrueCrypt Beginner's Tutorial, Part 3". Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- ↑ "RANDOM.ORG - True Random Number Service". www.random.org. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ The MathWorks. "Common generation methods". Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- ↑ The Numerical Algorithms Group. "G05 – Random Number Generators" (PDF). NAG Library Manual, Mark 23. Retrieved 2012-02-09.

- ↑ W. A. Wagenaar (1972). "Generation of random sequences by human subjects: a critical survey of the literature". Psychological Bulletin 77 (1): 65–72. doi:10.1037/h0032060.

- ↑ Dömstedt, B. (2009). "TRNG9803 True Random Number Generator". Manufacturer: www.TRNG98.se.

- ↑ Wang, Yongge (2014). "Statistical Properties of Pseudo Random Sequences and Experiments with PHP and Debian OpenSSL". Heidelberg: Springer LNCS.

- ↑ matthew Green. "The Many Flaws of Dual_EC_DRBG".

- ↑ Matthew Green. "RSA warns developers not to use RSA products".

- ↑ "We don’t enable backdoors in our crypto products, RSA tells customers". Ars Technica.

- ↑ "Researchers can slip an undetectable trojan into Intel’s Ivy Bridge CPUs". Ars Technica.

- ↑ Theodore Ts'o. "I am so glad I resisted pressure from Intel engineers to let /dev/random rely only on the RdRand instruction.". Google Plus.

- ↑ Theodore Ts'o. "Re: [PATCH] /dev/random: Insufficient of entropy on many architectures". LWN.

- ↑ "Random Number God - TV Tropes". TV Tropes.

Further reading

- Donald Knuth (1997). "Chapter 3 – Random Numbers". The Art of Computer Programming. Vol. 2: Seminumerical algorithms (3 ed.).

- Kroese, D. P.; Taimre, T.; Botev, Z.I. (2011). "Chapter 1 – Uniform Random Number Generation". Handbook of Monte Carlo Methods. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 772. ISBN 0-470-17793-4.

- Press, WH; Teukolsky, SA; Vetterling, WT; Flannery, BP (2007). "Chapter 7. Random Numbers". Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8

- NIST SP800-90A, B, C series on random number generation

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Random. |

- Random and Pseudorandom on In Our Time at the BBC.

- Clewett, James. "Random Numbers". Numberphile. Brady Haran.

- jRand a Java-based framework for the generation of simulation sequences, including pseudo-random sequences of numbers

- Random number generators in NAG Fortran Library

- Randomness Beacon at NIST, broadcasting full-entropy bit-strings in blocks of 512 bits every 60 seconds. Designed to provide unpredictability, autonomy, and consistency.

- A system call for random numbers: getrandom(), a LWN.net article describing a dedicated Linux system call

- Statistical Properties of Pseudo Random Sequences and Experiments with PHP and Debian OpenSSL

- Cryptographic ISAAC pseudorandom lottery numbers generator

- Random Sequence Generator based on Avalanche Noise