Rain shadow

A rain shadow is a dry area on the lee side of a mountainous area (away from the wind). The mountains block the passage of rain-producing weather systems and cast a "shadow" of dryness behind them.

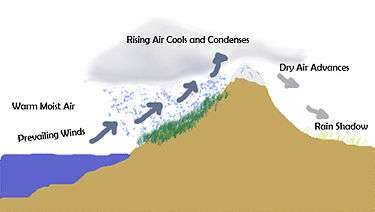

As shown by the diagram, the incoming warm and moist air is drawn by the prevailing winds towards the top of the mountains, where it condenses and precipitates before it crosses the top. The air, without much moisture left, advances behind the mountains creating a drier side called the "rain shadow".

Description

The condition exists because warm moist air rises by orographic lifting to the top of a mountain range. As atmospheric pressure decreases with increasing altitude, the air has expanded and adiabatically cooled to the point that the air reaches its adiabatic dew point (which is not the same as its constant pressure dew point commonly reported in weather forecasts). At the adiabatic dew point, moisture condenses onto the mountain and it precipitates on the top and windward sides of the mountain. The air descends on the leeward side, but due to the precipitation it has lost much of its moisture. Typically, descending air also gets warmer because of adiabatic compression (see Foehn winds) down the leeward side of the mountain, which increases the amount of moisture that it can absorb and creates an arid region.[1]

Regions of notable rain shadow

There are regular patterns of prevailing winds found in bands round the Earth's equatorial region. The zone designated the trade winds is the zone between about 30° N and 30° S, blowing predominantly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere. The westerlies are the prevailing winds in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude, blowing predominantly from the southwest in the Northern Hemisphere and from the northwest in the Southern Hemisphere. The strongest westerly winds in the middle latitudes can come in the Roaring Forties between 30 and 50 degrees latitude.

Examples of notable rain shadowing include:

Asia

- The peaks of the Caucasus Mountains to the west and Hindukush and Pamir to the east rain shadow the Karakum and Kyzyl Kum deserts east of the Caspian Sea, as well as the semi-arid Kazakh Steppe.

- The Judean Desert and the Dead Sea are rain shadowed by the Judean Hills.

- The Dasht-i-Lut in Iran is in the rain shadow of the Elburz and Zagros Mountains and is one of the most lifeless areas on Earth.

- The Himalaya and connecting ranges also contribute to arid conditions in Central Asia including Mongolia's Gobi desert, as well as the semi-arid steppes of Mongolia and north-central to north western China.

- The Ordos Desert is rain shadowed by mountain chains including the Kara-naryn-ula, the Sheitenula, and the Yin Mountains, which link on to the south end of the Great Khingan Mountains.

- The Thar desert is bounded and rain shadowed by the Aravalli ranges to the south-east, the Himalaya to the northeast, and the Kirthar and Sulaiman ranges to the west.

- Eastern Side of Sahyadri ranges on Deccan e.g. Northern Karnataka & Solapur, Beed, Osmanabad and Vidharba Plateau of India.

- The central region of Myanmar is in the rain shadow of the Arakan Mountains and is almost semi-arid with only 750 millimetres (30 in) of rain as against as much as 5.5 metres (220 in) on the Rakhine State coast.

- The Tokyo, Japan plain ("Kanto plain") in the winter months experiences significantly less precipitation than the rest of the country by virtue of surrounding mountain ranges, including the "Japan Alps", blocking prevailing northwesterly winds originating in Siberia.

South America

- The Atacama Desert in Chile is the driest non-polar desert on Earth because it is blocked from moisture on both sides (because the Andes Mountains to the east blocks moist Amazon basin air and high pressure over the Pacific and cold ocean currents keeps rain from coming in from the west).

- The Argentinian wine region of Mendoza is almost completely dependent on irrigation, using water drawn from the many rivers that drain glacial ice from the Andes. The nearby Chilean wine region of Valle Central on the other hand, is situated on the Chilean side of the Andes and experiences a maritime climate.

- Cuyo and Eastern Patagonia is rain shadowed from the prevailing westerly winds by the Andes range and is arid. The aridity of the lands next to eastern piedmont of the Andes decreases to the south due to a decrease in the height of the Andes with the consequence that the Patagonian Desert develop more fully at the Atlantic coast contributing to shaping the climatic pattern known as the Arid Diagonal.[2]

- The Guajira Peninsula in northern Colombia is in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and despite its tropical latitude is almost arid, receiving almost no rainfall for seven to eight months of the year and being incapable of cultivation without irrigation.

North America and the Caribbean

On the largest scale, the entirety of the North American Interior Plains are shielded from the prevailing Westerlies carrying moist Pacific weather by the North American Cordillera. More pronounced effects are observed, however, in particular valley regions within the Cordillera, in the direct lee of specific mountain ranges. Most rainshadows in the western United States are due to the Sierra Nevada and Cascades.[3]

- The deserts of the Basin and Range Province in the United States and Mexico, which includes the dry areas east of the Cascade Mountains of Oregon and Washington and the Great Basin, which covers almost all of Nevada and parts of Utah are rain shadowed. The Cascades also cause rain shadowed Columbia Basin area of Eastern Washington and valleys in British Columbia, Canada - most notably the Thompson and Nicola Valleys which can receive less than 10 inches of rain in parts, and the Okanagan Valley (particularly the south, nearest to the US border) which receives anywhere from 12-17 inches of rain annually.[4][5]

- Hawaii also has rain shadows, with some areas being desert.[6] Orographic lifting produces the world's second-highest annual precipitation record, 12.7 meters (500 inches), on the island of Kauai; the leeward side is understandably rain-shadowed.[1] The entire island of Kahoolawe lies in the rain shadow of Maui's East Maui Volcano.

- The east slopes of the Coast Ranges in central and southern California also cut off the southern San Joaquin Valley from enough precipitation to ensure desert-like conditions in areas around Bakersfield.

- San Jose, California and adjacent cities are usually drier than the rest of the San Francisco Bay Area because of the rain shadow cast by the highest part of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

- The Dungeness Valley around Sequim, Washington lies in the rain shadow of the Olympic Mountains. The area averages 10–15 inches of rain per year, less than half of the amount received in nearby Port Angeles and approximately 10% of that which falls in Forks on the western side of the mountains. To a lesser extent, this rain shadow extends to other parts of the eastern Olympic Peninsula, Whidbey Island, and parts of the San Juan Islands and southeastern Vancouver Island around Victoria, British Columbia.

- The Mojave, Black Rock, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan deserts all are in regions which are rain shadowed.

- The Owens Valley in the United States, behind the Sierra Nevada range in California.

- The aptly named Death Valley in the United States, behind both the Pacific Coast Ranges of California and the Sierra Nevada range, is the driest place in North America and one of the driest places on the planet. This is also due to its location well below sea level which tends to cause high pressure and dry conditions to dominate due to the greater weight of the atmosphere above.

- The Colorado Front Range is limited to precipitation that crosses over the Continental Divide. While many locations west of the Divide may receive as much as 40 inches (1,000 mm) of precipitation per year, some places on the eastern side, notably the cities of Denver and Pueblo, Colorado, typically receive only about 12 to 19 inches. Thus, the Continental Divide acts as a barrier for precipitation. This effect applies only to storms traveling west-to-east. When low pressure systems skirt the Rocky Mountains and approach from the south, they can generate high precipitation on the eastern side and little or none on the western slope.

- The Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, wedged between the Appalachian Mountains and the Blue Ridge Mountains and partially shielded from moisture from the west and southeast, is much drier than the very humid remainder of Virginia and the American Southeast.[7]

- On the islands of Hispaniola, Cuba and Jamaica, the southwestern sides are in the rain shadow of the trade winds and can receive as little as 400 millimetres (16 in) per year as against over 2,000 millimetres (79 in) on the northeastern, windward sides and over 5,000 millimetres (200 in) over some highland areas.

Europe

- The Pennines of Northern England, Welsh mountains, Lake District and Highlands of Scotland create a rain shadow that includes most of the eastern United Kingdom, due to the prevailing south-westerly winds. Manchester and Glasgow, for example, receive around double the rainfall of Sheffield and Edinburgh respectively (although there are no mountains between Edinburgh and Glasgow). The contrast is even stronger further north, where Aberdeen gets around a third of the rainfall of Fort William or Skye. The Fens of East Anglia receive similar rainfall amounts to Seville.[8]

- The Cantabrian Mountains form a sharp divide between "Green Spain" to the north and the dry central plateau. The northern-facing slopes receive heavy rainfall from the Bay of Biscay, but the southern slopes are in rain shadow. The most evident effect on the Iberian Peninsula occurs in the Almería, Murcia and Alicante areas, each with an average rainfall of 300 mm, which are the driest spots in Europe (see Cabo de Gata) mostly a result of the mountain range running through their western side, which blocks the westerlies.

- Some valleys in the inner Alps are also strongly rainshadowed by the high surrounding mountains: the areas of Gap and Briançon in France, the district of Zernez in Switzerland.

- The eastern part of the Pyrenean mountains in the south of France (Cerdagne).

- The Plains of Limagne and Forez in the northern Massif Central, France, are also relatively rainshadowed (mostly the plain of Limagne, shadowed by the Chaîne des Puys (up to 2000 mm of rain a year on the summits and below 600mm at Clermont-Ferrand, which is one of the driest places in the country).

- The Piedmont wine region of northern Italy is rainshadowed by the mountains that surround it on nearly every side: Asti receives only 527 mm of precipitation per year, making it one of the driest places in mainland Italy.[9]

- The valley of the Vardar River and south from Skopje to Athens is in the rain shadow of the Prokletije and Pindus Mountains. On its windward side the Prokletije has the highest rainfall in Europe at around 5,000 millimetres (200 in) with small glaciers even at mean annual temperatures well above 0 °C (32 °F), but the leeward side receives as little as 400 millimetres (16 in).

- The Scandinavian Mountains create a rain shadow for lowland areas east of the mountain chain and prevents the Oceanic climate from penetrating further east; thus Bergen, west of the mountains, receives 2,250 mm precipitation annually while Oslo receives only 760 mm, and Skjåk, a municipality situated in a deep valley, receives only 280 mm.

Africa

- The windward side of the island of Madagascar, which sees easterly on-shore winds, is wet tropical, while the western and southern sides of the island lie in the rain shadow of the central highlands and are home to thorn forests and deserts. The same is true for the island of Réunion. On Tristan da Cunha, Sandy Point on the east coast is warmer and drier than the rainy, windswept settlement of Edinburgh in the west.

- In Western Cape Province, the Breede River Valley and the Karoo lie in the rain shadow of the Cape Fold Mountains and are arid; whereas the wettest parts of the Cape Mountains can receive 1,500 millimetres (59 in), Worcester receives only around 200 millimetres (8 in) and is useful only for grazing.

- The Sahara Desert is made even drier because of two strong rain shadow effects caused by some major mountains ranges (whose highest points can culminate to more than 4,000 meters high). To the northwest, the Atlas Mountains, covering the Mediterranean coast for Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia as well as to the southeast with the Ethiopian Highlands, located in Ethiopia around the Horn of Africa. On the windward side of the Atlas Mountains, the warm, moist winds blowing from the northwest off the Atlantic Ocean which contain a lot of water vapor are forced to rise, lift up and expand over the mountain range. This causes them to cool down, which causes an excess of moisture to condense into high clouds and results in heavy precipitation over the mountain range. This is known as orographic rainfall and after this process, the air is dry because it has lost most of its moisture over the Atlas Mountains. On the leeward side, the cold, dry air starts to descend and to sink and compress, making the winds warm up. This warming causes the moisture to evaporate, making clouds disappear. This prevents rainfall formation and creates desert conditions in the Sahara. The same phenomenon occurs in the Ethiopian Highlands, but this rain shadow effect is even more pronounced because this mountain range is larger, with the tropical Monsoon of South Asia coming from the Indian Ocean and from the Arabian Sea. These produce clouds and rainfall on the windward side of the mountains, but the leeward side stays rain shadowed and extremely dry. This second extreme rain shadow effect partially explains the extreme aridity of the eastern Sahara Desert, which is the driest and the sunniest place on the planet. Similar levels of aridity and dryness are only seen in the Atacama Desert, located in Chile and Peru.

- Desert regions in the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia and Djibouti) such as the Danakil Desert are all influenced by the air heating and drying produced by rain shadow effect of the Ethiopian Highlands, too.

Oceania

- New Caledonia lies astride the Tropic of Capricorn, between 19° and 23° south latitude. The climate of the islands is tropical, and rainfall is brought by trade winds from the east. The western side of the Grande Terre lies in the rain shadow of the central mountains, and rainfall averages are significantly lower.

- In the South Island of New Zealand is to be found one of the most remarkable rain shadows anywhere on Earth. The Southern Alps intercept moisture coming off the Tasman Sea, precipitating about 6,300 mm (250 in) to 8,900 mm (350 in) liquid water equivalent per year and creating large glaciers. To the east of the Southern Alps, scarcely 50 km (30 mi) from the snowy peaks, yearly rainfall drops to less than 760 mm (30 in) and some areas less than 380 mm (15 in). (see Nor'west arch for more on this subject).

- In Tasmania, one of the states of Australia, the central Midlands region is in a strong rain shadow and receives only about a fifth as much rainfall as the highlands to the west.

- In New South Wales and Victoria (both states of Australia), the Monaro is shielded by both the Snowy Mountains to the northwest and coastal ranges to the southeast. Consequently, parts of it are as dry as the wheat-growing lands of those states.

- Also in Victoria, the western side of Port Phillip Bay is in the rain shadow of the Otway Ranges. The area between Geelong and Werribee is the driest part of southern Victoria: the crest of the Otway Ranges receives 2,000 millimetres (79 in) of rain per year and has myrtle beech rainforests much further west than anywhere else, whilst the area around Little River receives as little as 425 millimetres (16.7 in) annually, which is as little as Nhill or Longreach and supports only grassland.

- Western Australia's Wheatbelt and Great Southern regions are shielded by the Darling Range to the west: Mandurah, near the coast, receives about 700 millimetres (28 in) annually. Dwellingup, 40 km inland and in the heart of the ranges, receives over 1,000 millimetres (39 in) a year while Narrogin, 130 km further east, receives less than 500 millimetres (20 in) a year.

See also

References

- 1 2 Whiteman, C. David (2000). Mountain Meteorology: Fundamentals and Applications. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513271-8.

- ↑ Bruniard, Enrique D. (1982). "La diagonal árida Argentina: un límite climático real". Revista Geográfica (in Spanish): 5–20.

- ↑ "How mountains influence rainfall patterns". USA Today. 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Westerlies". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ↑ Sue Ferguson (2001-09-07). "Climatology of the Interior Columbia River Basin" (PDF). Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ↑ Giambelluca, Tom; Sanderson, Marie (1993). Prevailing Trade Winds: Climate and Weather in Hawaií. University of Hawaii Press. p. 62.

- ↑ http://www.cocorahs.org/Media/docs/ClimateSum_VA.pdf

- ↑ "UK Rainfall averages".

- ↑ "Asti weather". weatherbase.com.