Railway electrification in the Soviet Union

While the former Soviet Union got a late (and slow) start with rail electrification in the 1930s it eventually became the world leader in electrification in terms of the volume of traffic under the wires. During its last 30 years the Soviet Union hauled about as much rail freight as all the other countries in the world combined and in the end, over 60% of this was by electric locomotives. Electrification was cost effective due to the very high density of traffic and was at times projected to yield at least a 10% return on electrification investment (to replace diesel traction). By 1990, the electrification was about half 3 kV DC and half 25 kV AC 50 Hz and 70%[1] of rail passenger-km was by electric railways.

| Year | 1940 | 1945 | 1950 | 1955 | 1960 | 1965 | 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | 1988 | 1991 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrified Mm (Megametres) | 1.8 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 13.8 | 24.9 | 33.9 | 38.9 | 43.7 | 52.9 | 54.3 |

| % of Rail Network | 1.8 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 11.0 | 19.0 | 25.0 | 28.1 | 30.8 | 36.1 | |

| % of Rail Freight (in tonne-km) | 2.0 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 8.4 | 21.8 | 39.4 | 48.7 | 51.6 | 54.6 | 63.1 |

Comparison to the US and others

Compared to the US, the Soviet Union got off to a very slow start in electrification but later greatly surpassed the US. Electrification in the US reached its maximum of 5,000 km in the late 1930s[3] which is just when electrification was getting its start in the USSR.

About 20 years after the 1991 demise of the Soviet Union, China became the new world leader in rail electrification with 48 Mm electrified by 2013, and continuing to grow.[4]

| Country | USSR | Japan | West Germany | France |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mm of route electrified | 51.7 | 14 | 12 | 11 |

| Total Mm of railway route | 144 | 28 | 28 | 34 |

| Percentage of route electrified | 35.9% | 50.0% | 42.8% | 32.3% |

| Mm, direct current (DC) | 27.3 | 8 | 0.8 | 6 |

| Mm, Alternating current (AC) (50 Hz) | 24.4 | 6 | 11.2 (16 2⁄3 Hz) | 5 |

History

1920s: Lenin supports rail electrification

Replacing steam traction (on lines with high traffic) by electrification was cost effective[6] and this was the impetus for the first electrifications in the 1930s. The 1920 national electrification plan, GOELRO—ГОЭЛРО (Russian)[7] included railway electrification and was strongly supported by Lenin, the leader of the Soviet revolution. Lenin wrote a letter[8] implying that if rail electrification was not feasible at the present time, might it not be feasible in 5–10 years from now. And in fact, railway electrification actually got started about 10 years later but Lenin didn't live to see it happen.

1930s

Mainline railway electrification in the Soviet Union began in 1932 with the opening of a 3,000 V DC section in the Georgian SSR on the Surami Pass between the capital, Tbilisi, and the Black Sea.[9] The grade (slope) was steep: 2.9%. The original fleet of eight electric locomotives was imported from the United States and were made by General Electric (GE). The Soviets obtained construction drawings from GE enabling them to construct locomotives to the same design. The first electric locomotive constructed in the USSR was an indigenous design completed in November 1932. Later in the same month, the second locomotive, a copy of the GE locomotive, was completed. At first, many more copies of US design were made than ones of Soviet design—no more locomotives of Soviet design were made until two years later.

The 5-year plans for electrification in the 1930s all came up short. By October 1933, the first 5-year plan called for the electrification in the USSR to reach 456 km vs. 347 km actually achieved.[10] Future 5-year plans were even more under-fulfilled. For the 2nd 5-year plan (thru 1937) it was 5062 km planned vs 1632 actual. In the 3rd 5-year plan (thru 1942) it was 3472 vs. 1950 actual but the start of World War II in mid 1941 contributed to this shortfall.

World War II

By 1941, the USSR had electrified only 1,865 route-kilometers.[11] This was well behind the US, which had nearly 5,000 kilometers electrified.[12] However, since the USSR rail network was much shorter than the US, the percentage of Soviet rail kilometers electrified was greater than the US. During World War II as the western part of the Soviet Union (including Russia) was invaded by Nazi Germany. About 600 km of electrification was dismantled[13] but after the Germans were driven out, some dismantled electrification was reinstalled. After the war, the highest priority was to rebuild the destruction caused by the war, so major railway electrification was further postponed for about 10 years.

Post-war

In 1946 the USSR ordered 20 electric locomotives from General Electric,[14] the same US corporation that supplied locomotives for the first Soviet electrification. Due to the cold war, they could not be delivered to the USSR so they were sold elsewhere. The Milwaukee Road in the US obtained 12, nicknamed "Little Joes", "Joe" referring to Joseph Stalin, the Soviet premier. In the mid-1950s, the USSR launched a two-pronged approach to replace steam locomotives. They would electrify the lines with high density traffic and slowly convert the others to diesel. The result was a slow but steady introduction of both electric and diesel traction which lasted until about 1975 when their last steam locomotives were retired.[15] In the US, steam went out about 1960,[16] 15 years earlier than for the USSR.

Once dieselization and electrification had fully replaced steam they began to convert diesel lines to electric, but the pace of electrification slowed. By 1990, over 60% of railway freight was being hauled by electric traction.[17][18] This amounted to about 30% of the freight hauled by all railways in the world (by all types of locomotives)[19] and about 80% of rail freight in the US (where rail freight held almost a 40% modal share).[20] The USSR was hauling more rail freight than all the other countries in the world combined, and most of this was going by electrified railway.

Post-Soviet era

After the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991, railway traffic in Russia sharply declined[21] and new major electrification projects were not undertaken but work continued on some unfinished projects. The line to Murmansk was completed in 2005.[22][23] Electrication of the last segemnt of the Trans-Siberian Railway from Khabarovsk (Хабаровск) to Vladivostok (Владивосток) was completed in 2002.[24] By 2008, the tonne-kilometers hauled by electric trains in Russia had increased to about 85% of rail freight.[17]

Energy-efficiency

Compared to diesels

Partly due to inefficient generation of electricity in the USSR (only 20.8% thermal efficiency in 1950 vs. 36.2% in 1975), in 1950 diesel traction was about twice as energy efficient as electric traction (in terms of net tonne-km of freight per kg of fuel).[25] But as efficiency of electricity generation (and thus of electric traction) improved, by about 1965 electric railways became more efficient than diesel. After the mid 1970s electrics used about 25% less fuel per ton-km. However diesels were mainly used on single track lines with a fair amount of traffic [26] so that the lower fuel consumption of electrics may be in part due to better operating conditions on electrified lines (such as double tracking) rather than inherent energy efficiency. Nevertheless, the cost of diesel fuel was about 1.5 times[27] more (per unit of heat energy content) than that of the fuel used in electric power plants (that generated electricity), thus making electric railways even more energy-cost effective.

Besides increased efficiency of power plants, there was an increase in efficiency (between 1950 and 1973) of the railway utilization of this electricity with energy-intensity dropping from 218 to 124 kwh/10,000 gross tonne-km (of both passenger and freight trains) or a 43% drop.[28] Since energy-intensity is the inverse of energy-efficiency it drops as efficiency goes up. But most of this 43% decrease in energy-intensity also benefited diesel traction. The conversion of wheel bearings from plain to roller, increase of train weight,[29] converting single track lines to double track (or partially double track), and the elimination of obsolete 2-axle freight cars increased the energy-efficiency of all types of traction: electric, diesel, and steam.[28] However, there remained a 12–15% reduction of energy-intensity that only benefited electric traction (and not diesel). This was due to improvements in locomotives, more widespread use of regenerative braking (which in 1989 recycled 2.65% of the electric energy used for traction,[30]) remote control of substations, better handling of the locomotive by the locomotive crew, and improvements in automation. Thus the overall efficiency of electric traction as compared to diesel more than doubled between 1950 and the mid-1970s in the Soviet Union. But after 1974 (thru 1980) there was no improvement in energy-intensity (wh/tonne-km) in part due to increasing speeds of passenger and freight trains.[31]

DC vs. AC

In 1973 (per the table below), DC traction at 3,000 volts, lost about 3 times as much energy (percentage-wise) in the catenary as AC at 25,000 volts. Paradoxically, it turned out that DC locomotives were somewhat more efficient overall than AC locomotives. "Auxiliary Electric Motors" are mainly used for air cooling electric machinery such as traction motors. Electric locomotives concentrate high power electric machinery in a relatively small space and thus require a lot of cooling.[32] Per the table below, a sizeable amount of energy (11–17%) is used for this, but when operating at nominal power only 2–4% is used.[33] The fact that the cooling motors run at full speed (and power) all the time makes their power consumption constant, so when the locomotive motors are operating at low power (far below the nominal regime) the percent of this power used for cooling blowers becomes much higher. The result is that under actual operating conditions, the percent energy used for cooling is a few times higher than "nominal". Per the table below, AC locomotives used about 50% more energy for this purpose since in addition to cooling the motors, the blowers must cool the transformer, rectifiers and the smoothing reactor (inductors), which are mostly absent on DC locomotives.[34] The 3-phase AC power for these blower motors is supplied from a rotary phase converter which converts single phase (from the catenary via the main transformer) to 3-phase (and this also takes energy). It's proposed to reduce blower speeds when less cooling is needed.[35]

| Type of current | DC | AC |

|---|---|---|

| Catenary | 8.0 | 2.5 |

| Substations | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| Onboard rectifier | 0 | 4.4 |

| Auxiliary electric motors | 11.0 | 17.0 |

| Traction motors and gears | 77.0 | 74.1 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Traction motor and gears efficiency

While the above table shows that about 75% of the electric energy supplied to the rail substation actually reaches the electric traction motors of the locomotive, the question remains as to how much energy is lost in the traction motor and the simple gear transmission (only two gear wheels). Some in the USSR thought it was about 10% (90% efficient).[37] But counter to this, it was claimed that the actual loss was significantly higher than this since the average power used by locomotive when "in motion" was only roughly 20% of nominal power, with lower efficiency at lower power levels. However, checking Russian books on the subject indicates that the supporters of 90% efficiency may not be too far off the mark.[38]

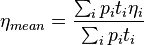

When calculating average efficiency over a period of time, one needs to take an average of efficiencies weighted by the product of power input and time (of that segment of power input):  where

where  is the power input and

is the power input and  is the efficiency during time

is the efficiency during time  [39] If efficiency is low at very low power, then this low efficiency has a low weighting due to the low power (and the low amount of energy thus consumed). Conversely, high efficiencies (presumably at high power) get high weighting and thus count for more. This may result in a higher average efficiency than would be obtained by simply averaging efficiency over time. Another consideration is that the efficiency curves (that plot efficiency vs. current) tend to drop off rapidly at both low current and very high current for traction motor efficiency, and at low power for gear efficiency) so it is not a linear relationship. Investigations [40] for diesel locomotives show that the lower notches (except notch 0 which is "motor off") of the controller (and especially notch 1 – the lowest power) are much less used than the higher notches. At very high currents, the resistive loss is high since it is proportional to the square of the current. While a locomotive may exceed the nominal current, if it goes too high the wheels will start slipping.[41] So the unanswered question is just how often is nominal current exceeded and for how long? The instructions for starting a train from a stop [42] suggest exceeding the current where the wheels would normally start to slip, but to avoid such slipping by putting sand on the rails (either automatically or by depressing a "sand" button just as the wheels start to slip).

[39] If efficiency is low at very low power, then this low efficiency has a low weighting due to the low power (and the low amount of energy thus consumed). Conversely, high efficiencies (presumably at high power) get high weighting and thus count for more. This may result in a higher average efficiency than would be obtained by simply averaging efficiency over time. Another consideration is that the efficiency curves (that plot efficiency vs. current) tend to drop off rapidly at both low current and very high current for traction motor efficiency, and at low power for gear efficiency) so it is not a linear relationship. Investigations [40] for diesel locomotives show that the lower notches (except notch 0 which is "motor off") of the controller (and especially notch 1 – the lowest power) are much less used than the higher notches. At very high currents, the resistive loss is high since it is proportional to the square of the current. While a locomotive may exceed the nominal current, if it goes too high the wheels will start slipping.[41] So the unanswered question is just how often is nominal current exceeded and for how long? The instructions for starting a train from a stop [42] suggest exceeding the current where the wheels would normally start to slip, but to avoid such slipping by putting sand on the rails (either automatically or by depressing a "sand" button just as the wheels start to slip).

Inspecting a graph of traction motor gear efficiency [43] shows 98% efficiency at nominal power but only 94% efficiency at 30% of nominal power. To get the efficiency of the motor and gears (connected in series), the two efficiencies must be multiplied. If the weighted traction motor efficiency is 90%, then 90% x 94% = 85% (very rough estimate) which is not too much lower than that estimated the 90% supporters mentioned above. If per the table 75% of power to the substation reaches the locomotive motors then 75% x 85 = 64% (roughly) of the power to the substation (from the USSR's power grid) reaches the wheels of the locomotives in the form of mechanical energy to pull the trains. This neglects the power used for "housekeeping" (heating, lighting, etc.) on passenger trains. This is over the whole range of operating conditions in the early 1970s. There are a number of ways to significantly improve this 64% figure and it fails to take into account savings due to regeneration (using the traction motors as generators to put power back on the catenary to power other trains).

Economics

Overview

In 1991 (the final year of the Soviet Union) the cost of electrifying one kilometer was 340–470 thousand rubles[44] and required up to 10 tonnes of copper. Thus it was expensive to electrify. Are the savings due to electrification worth the cost? As compared to inefficient steam locomotives, it's easy to make the case for electrification.[45] But how does electrification economically compare with diesels locomotives which started to be introduced in the USSR in the mid 1930s and were significantly less costly than steam traction?[46] Later on there were even whole books written on the topic of comparing the economies of electric vs. diesel traction[47]

Electrification requires high fixed costs but results in savings in operating cost per tonne-km hauled. The more tonne-km, the greater this savings, so that higher traffic will result in savings that more than cover the fixed costs. Steep grades also favor electrification, partly because regenerative braking can recover some energy when descending the grade. Using the formula below to compare diesel to electric on a double track line with Ruling gradient of 0.9 to 1.1% and density of about 20 million t-km/km (or higher) results in less cost for electric with an assumed 10% return required on the capital investment.[48] For lower traffic, diesel traction will be more economical per this methodology.

Return on investment formula

The decision to electrify is supposed to be based on return on investment and examples are given which proposed electrification only if the investment in electrification would not only pay for itself in lower operating cost but in addition would give a percentage return on the investment. Example percentage returns on investment are 10%[49] and 8%.[50] In comparing two (or more) alternatives (such as electrification or dieselization of a rail line) one calculates the total annual cost, using a certain interest return on capital and then selects the least cost alternative. The formula for total annual cost is: Эпрi=Эi+ЕнКi[51] where the subscript i is the i th alternative (all the other letters except i are in the Russian alphabet), Эi is the annual cost of alternative i (including amortization of capital), Ен is the interest rate, and Кi is the value (price) of the capital investment for alternative i. But none of the references cited here (and elsewhre) call Ен an interest rate. Instead, they describe it as the inverse of the number of years required to have the net benefits of the investment pay off the investment where the net benefits are calculated net of paying amortization "costs" of the investment. Also, different books sometimes use different letters for this formula.

Fuel/power costs

In the early 1970s, the cost of providing mechanical energy to move trains (locomotive operating costs) amounted to 40–43% of the total operating cost of the railways.[52] This includes the cost of fuel/electric-power, operating/maintaining locomotives (including crew wages), maintaining the electric power system (for electrified lines), and depreciation. Of the cost of providing this mechanical energy (locomotive operating costs), fuel and power costs amounted to 40–45%. Thus fuel/power costs are very significant cost components and electric traction generally uses less energy (see #Energy-efficiency).

One may plot fuel cost per year as a function of traffic flow (in net tonnes/year in one direction) for various assumptions (of ruling grades, locomotive model, single or double track,[53] and fuel/power prices), resulting· in a large number of such plotted curves.[54] For early 1970s energy prices of 1.3 kopecks/kwh and 70 roubles/tonne for diesel fuel, these curves (or tables based on them) show the fuel/power costs to be very roughly 1.5 to 2 time higher for diesel operation as for electric.[55] The exact ratio, of course, depends on the various assumptions and in extreme cases of low diesel fuel prices (45 roubles/tonne) and high electricity cost (1.5 kopecks/kwh), diesel fuel costs of rail movement are lower than electricity costs.[56] All of these curves show the difference in energy cost (of diesel vs. electric) increases with traffic flow. One may approximate the above-mentioned curves by cubic functions of the traffic flow (in net tonnes/year) with the coefficients being linear functions of fuel/power prices. In mathematics, such coefficients are usually shown as constants, but here they are also mathematical functions[57] Such use of mathematical formulas facilitates computerized evaluation of alternatives.

Non-fuel/power costs

In a sense, these are components of the costs of mechanical energy delivered to the wheels of the locomotive but they are neither liquid fuel nor electricity. While electric traction usually saves on fuel/power costs, what about the other cost comparisons? Of the costs of locomotive operation, the maintenance and repair costs for electric locomotives amounted to about 6% as compared to 11% for diesel locomotives.[52] Besides lower maintenance/repair costs it's claimed that the labor (crew) cost of operating electric locomotives is a little lower for electrics. Lubrication costs is less for electrics (they have no diesel engines to fill with lubricating oil).[58]

Countering the cost advantages of electric traction are the cost disadvantages of electrification: primarily the costs of the catenary and substations (including maintenance costs). It turns out that roughly half of the yearly cost is for depreciation to pay back the original cost of the installation and the other half is for maintenance.[59] An important factor was the use of the railway electric power system in the Soviet Union to supply public power to residences, farms, and non-rail industry which in the early 1970s consisted of about 65% of the electric energy used by trains. Thus the sharing of costs of electrification with external electricity consumers reduces the cost of rail electrification resulting in reduced yearly electrification costs of 15–30%. It's claimed that this cost sharing significantly unfairly favored the external users of electricity at the expense of the railway.[60] However (in the early 1970s) it's claimed that the annual cost of rail electrification (including maintenance) was only a third to a half of the benefits of savings in fuel costs thus favoring electric traction (if the interest cost of capital is neglected and the traffic is fairly high).

Historical costs of locomotive operation: Electric vs. Diesel

The following table shows these costs for both 1960 and 1974 in roubles per 100,000 tonne-km gross haulage of freight. These costs include capital cost by the use of depreciation charges (in a non-inflation environment).

| Year | 1960 | 1974 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type Locomotive | Electric | Diesel | Electric | Diesel |

| Total operating cost | 35.13 | 35.34 | 35.1 | 48.8 |

| Including: | ||||

| Locomotive repairs and maintenance | 1.27 | 3.39 | 1.4 | 3.72 |

| Electricity or fuel | 15.42 | 12.91 | 15.18 | 21.18 |

| Wages of locomotive crews | 4.69 | 5.84 | 4.33 | 6.25 |

| Overhead and other | 4.09 | 7.16 | 4.51 | 9.44 |

| Depreciation | 9.99 | 6.57 | 9.68 | 8.12 |

Note that "depreciation" for electric traction includes maintenance and depreciation charges for the catenary and electric substations. For both types of traction, depreciation of the repair shops are included. For diesel traction there is depreciation of fueling facilities. The higher depreciation of the diesel locomotive is more than made up for by the depreciation of the catenary and substations for the case of electric traction.

In 1960 electric and diesel were about equal in cost but in 1974, after a significant increase in the price of diesel fuel due to the 1973 oil crisis, electric traction became lower in cost. Note that there are no interest charges added to depreciation.

Total yearly cost comparison

Per the calculations by Dmytriev[62] Even a low traffic-density line with 5 million tonne-km/km (in both directions) will pay back the cost of electrification if the interest rate is zero (Ен=0)[63] (no return on investment). As traffic density increases, the ratio of diesel to electric yearly expenses (including depreciation) increases. In an extreme case (traffic density 60 million tonne-km/km, and 1.1% ruling grade), diesel operating costs (including depreciation) are 75% higher than electric. Thus it really pays to electrify lines with high density traffic.

| Number of tracks | Single track | Double track | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Million tonne-km/km density (both directions) | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 40 | 60 |

| Ratio of operating cost in %: diesel/electric | 104 | 119 | 128 | 131 | 149 | 155 |

Electrical systems

Voltage and Current

The USSR originally selected 3,000 V DC for mainline electrification. Even then in the early 1930s, it was realized that it was too low of a voltage for the catenary but too high for optimal motors. The solution to this problem was to use 25 kV AC for the catenary and provide on-board transformers to step down the 25 kV to a much lower voltage where it was then rectified to give low voltage DC. Another proposal was to use 6,000 V DC(Russian) where the high voltage DC would be reduced by power electronics before being applied to motors. Only one experimental train set at 6 kV was made and it only operated in the 1970s. In the last years of the Soviet Union a debate was in progress as to whether the 3,000 V DC system should be converted to a 12 kV DC system or to the standard 25 kV system.[65] 12 kV DC was claimed to have the same technical-economic advantages as 25 kV AC while costing less and putting a balanced load on the nation's AC power grid (there is no Reactive power problem to deal with). Opponents pointed out that it would create a third standard electrification system in the USSR.

Examples of electric locomotives

(Russian) Site with 34 articles on 34 Soviet electric locomotives

3 kV DC

25 kV AC

Dual voltage

See also

- Elektrichka

- Electrification of Saint Petersburg Railway Division

- History of rail transport in Russia

- Rail transport in the Soviet Union

- Trams of Putilov plant

Notes

- 1 2 For 1991 see РИА Новости (RIA News; RIA=Russian Information Agency) 29.08.2004 section Экономика (Economics): "Исполняется 75 лет электрификации железных дорог России" (75th anniversary of electrification of railways in Russia)

- ↑ Ицаев table 1.2, p.30. Исаев uses the term "перевозочная робота" (transportation work) to mean tonne-km of freight since the same data as in his table 1.2 is also found in table 4 of Димитриев (p. 43) where it is more precisely labeled as "грузообороте" which unambiguously translates into tonne-km of freight. For 1950 see Дмитриев table 4., p. 43.

- ↑ see "The mystique of electrification" by David P. Morgan, Trains (magazine), July 1970, p.44+. He states that electrification reached its peak (in the US) of 3100 miles (1.23% of route-miles) but fails to give a date. But from the context, the date is between 1924–1957. The last major electrification was by the Pennsy (Pennsylvania Railroad) during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Since electrified mileage had decreased by 2/3 by 1957 (per Morgan) then the peak must have been well before 1957. With the big Pennsy electrification going on in the 1930s, total electrified mileage was likely increasing. This reasoning puts the peak at the end of the 1930s. Дмитриев p. 116 claims that there was almost no new electrification in the US from 1938-1973 which lends more credibility to the guesstimated time of the peak. Statistics on electrification may be found in the annual reports of the now defunct "Interstate Commerce Commission" (but have not yet been checked). Titles include "Annual report of the statistics of railways in the United States" (before 1955) and "Annual report on transport statistics in the United States"

- ↑ See "Peoples Daily Online" (in English, newspaper) 5 December 2012 China's electric railway mileage exceeds 48,000 km

- ↑ Исаев table 1.1, p. 22.

- ↑ Дмитриев (Russian) p.42; Раков (Russian) p.392

- ↑ an acronym for Государственная комиссия по электрификации России (Government commission for electrification of Russia). See Дмитриев (Russian) pp. 13-14; ГОЭЛРО (Russian)

- ↑ Дмитриев (Russian) p. 15

- ↑ Раковx (Russian) p. 394+ See 11.2 Сурамские электровозы (Surami electric locomotives)

- ↑ Westwood. See pp. 173 and 308: Table 36: "Railway electrification: plans and achievement, 1930s ..."

- ↑ Плакс (Russian), 1993, See 1.2 (p.7+)

- ↑ Morgan, David P., "The Mystique of Electrification", Trains, July 1970. p. 44

- ↑ Исаев (Russian) p.25

- ↑ Middleton, William D., "Those Russian Electrics", Trains, July 1970. pp. 42-3. Middleton, William D. "When the steam railroads electrified 2nd ed." Univ. of Indiana, 2001. p.238

- ↑ Плакс (Russian), p. 7 Fig. 1.3

- ↑ Railroad Facts: Table: Locomotives in Service

- 1 2 Freight by electric railway 2008 (Russian)

- ↑ Плакс (Russian), p. 3 (no 3 printed on p. but has heading: "От авторов")

- ↑ United Nations (Statistical Office) Statistical Yearbook. See tables in older issues titled: "World railway traffic". This table has since been discontinued.

- ↑ "Transportation in America", Statistical Analysis of Transportation in the United States (18th edition), with historical compendium 1939-1999, by Rosalyn A. Wilson, pub. by Eno Transportation Foundation Inc., Washington DC, 2001. See table: Domestic Ton-Miles by Mode, p.12

- ↑ United Nations (UN) Statistical Yearbook, 40th p. 514; UN 48th p. 527

- ↑ Murmansk Electrification (Russian)

- ↑ Electrification Completed (Russian)

- ↑ Transsiberian electrification (Russian)

- ↑ Планкс Fig. 1.2, p.6. Дмитриев, Table 1, p.20

- ↑ Хомич p.8

- ↑ Плакс, p.6

- 1 2 Перцовский p.39

- ↑ Higher weight may decrease specific train resistance due to economies of scale in Rolling resistance and Aerodynamic Drag

- ↑ Калинин p. 4

- ↑ Мирошниченко pp.4,7(Fig.1.2б)

- ↑ Захарченко p.4

- ↑ Перцовский p.40

- ↑ Сидоров 1988 pp. 103-4, Сидоров 1980 pp. 122-3

- ↑ Перцовский p.42, claims that by installing converters on AC locomotives to change the 50 Hz auxiliary power (for the cooling motors) to 16 2/3 Hz could reduce air cooling consumption by a factor of 15. This implies that some of the time blowers would run at 1/3 speed. See Induction motor#Principles of operation where the rotating image is for an asynchronous, 4-pole, 3-phase motor. Six such motors (АЭ-92-4 40 kW each) were used on the Soviet VL60^k AC locomotive for cooling traction motors, the transformer, smoothing reactors, rectifiers, etc. See Новочеркасский pp,46,58. Per Engineering Letter 2, The New York Blower Company, 7660 Quincy Street, Willowbrook, Illinois 60521. Section "Fan Laws" law 3, fan power varies with the cube of the speed so at 1/3 of the speed only 1/27 of the power would be used. Thus the claim of a 15-fold reduction is not completely unreasonable.

- ↑ Перцовский table 3, p.41.

- ↑ Перцовский3, p. 41

- ↑ A book on diesel efficiency (Хомич p. 10) indicates that the time "in motion" includes the time spent stopping to let other trains pass, as well as the time spent coasting. Diesel freight locomotives spent about 1/3 of their time while on a run, either coasting or stopped (trains in the Soviet Union did a lot of coasting to save energy). If the same statistics were to hold for electric locomotives, the percent utilization of power would increase from 20% to about 30%, since the traction motors would be shut off 1/3 of the time and this time shouldn't count since the question should be "during the time the locomotive is supplying power, what percent of the locomotive power is being utilized". Efficiency depends on various factors. Винокуров p. 101 shows efficiency reaching a maximum at 75% of nominal current which is no more than 75% of nominal power. For low-speed operation, it shows maximum efficiency occurring at about 40% of nominal current. He states that efficiencies range from 90 to 95% but the curves show under 80% at very low (10% of nominal) or very high currents (125% of nominal). Efficiency also depends on the amount of magnetic field weakening (Винокуров p. 54, Fig. 11). Lower fields are more efficient.

- ↑ If one is finding thermal efficiencies, power usually means output power (mechanical or electrical). In this case one must take the weighted harmonic mean of efficiencies weighted by output power as in the equation on p. 7 of Хомич

- ↑ Хомич pp. 10–12

- ↑ Новочеркасский p. 259, fig. 222. shows the speed-current curves for each of the 33 controller positions (plus 3 field weakening positions) and intersecting these curves is a bold line of the adhesion limit where the wheels are likely to start slipping.)

- ↑ Новочеркасский p. 308

- ↑ Захарченко p. 19 fig. 1.7

- ↑ Планкс p.7

- ↑ Дмитриев pp. 105-6

- ↑ Дмитриев p. 34, Раков Ch. 11 Электровозы (Electric Locomotives) p. 392

- ↑ One such book is Дмитриев and at the bottom of p.118, several organizations are listed which published reports on this topic.

- ↑ Дмитриев, p. 237

- ↑ Дмитриев: 0.1 (10%) is substituted on p.245 into the formula on the bottom of p. 244

- ↑ Soviet Encyclopedia; Приведённые затрат (total cost including interest)

- ↑ Дмитриев p. 236

- 1 2 Дмитриев p. 225

- ↑ For single track, opposing trains must stop at sidings to pass each other, resulting in more energy use (and more potential for regenerative braking)

- ↑ Дмитриев p. 226, Figs. 31,32

- ↑ Дмитриев pp. 228-9

- ↑ Дмитриев p. 228, table 58

- ↑ Дмитриев pp. 226-7

- ↑ Дмитриев p.231 table 60

- ↑ Дмитриев p. 229, table 59

- ↑ Дмитриев p. 230

- ↑ Дмитриев p.55

- ↑ Дмитриев p. 233 table 61

- ↑ See #Return on investment formula

- ↑ Дмитпиев p. 233, table 61

- ↑ Фукс Н.Л. "О выборе системы электрической тяги" (About the selection of systems of electric traction) Ж/Д Транс. 3-1989, pp. 38-40

Bibliography (English)

Westwood J.N. "Transport" chapter in book "The Economic Transformation of the Soviet Union, 1913-1945" ed. by Davies, R.W. et al., Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Bibliography (Russian)

- Винокуров В.А., Попов Д.А. "Электрические машины железно-доровного транспорта" (Electrical machinery of railroad transportation), Москва, Транспорт, 1986, . ISBN 5-88998-425-X, 520 pp.

- Дмитриев, В. А.; "Народнохозяйственная эффективность электрификации железных дорог и примениния тепловозной тяги" (National economic effectiveness of railway electrification and application of diesel traction), Москва, "Транспорт" 1976.

- Захарченко Д.Д., Ротанов Н.А. "Тяговые электрические машины" (Traction еlectrical machinery) Москва, Транспорт, 1991, ISBN 5-277-01514-0. - 343 pp.

- Ж/Д Транс.=Железнодорожный транспорт (Zheleznodorozhnyi transport = Railway transportation) (a magazine)

- Исаев, И. П.; Фрайфельд, А. В.; "Беседы об электрической железной дороге" (Discussions about the electric railway) Москва, "Транспорт", 1989.

- Калинин, В.К. "Электровозы и электроноезда" (Electric locomotives and electric train sets) Москва, Транспорт, 1991. ISBN 978-5-277-01046-4

- Курбасов А.С., Седов, В.И., Сорин, Л.Н. "Проектипование тягожых электро-двигателей" (Design of traction electric motors) Москва, транспорт, 1987.

- Мирошниченко, Р.И., "Режимы работы электрифицированных участков" (Regimes of operation of electrified sections [of railways]), Москва, Транспорт, 1982.

- Новочеркасский электровозостроительный завод (Novocherkass electric locomotive factory) "Электровоз БЛ60^к Руководство по эксплутации" (Electric locomotive VL60k, Operating handbook), Москва, Транспорт, 1976.*

- Перцовский, Л. М.; "Энргетическая эффективность электрической тяги" (Energy efficiency of electric traction), Железнодорожный транспорт (magazine), #12, 1974 p. 39+

- Плакс, А. В. & Пупынин, В. Н., "Электрические железные дороги" (Electric Railways), Москва "Транспорт" 1993.

- Раков, В. А., "Локомотивы отечественных железных дорог 1845-1955" (Locomotives of our country's railways) Москва "Транспорт" 1995.

- Сидоров Н.И., Сидорожа Н.Н. "Как устроен и работает эелктровоз" (How the electric locomotive works) Москва, Транспорт, 1988 (5th ed.) - 233 pp, Как устроен и работает электровоз at Google Books ISBN 978-5-458-48205-9. 1980 (4th ed.).

- Хомич А.З. Тупицын О.И., Симсон А.Э. "Экономия топлива и теплотехническая модернизация тепловозов" (Fuel economy and the thermodynamic modernization of diesel locomotives) - Москва: Транспорт, 1975 - 264 pp.

- Цукадо П.В., "Экономия электроэнергии на электро-подвижном составе" (Economy of electric energy for electric rolling stock), Москва, Транспорт, 1983 - 174 pp.