Raid of Żejtun

| Raid of Żejtun | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman-Habsburg wars | |||||||

Chapel of St. Gregory (then Parish Church of St. Catherine), which was sacked by the Ottomans | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000–6,000 men | c. 6,000–8,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Some killed c. 50 captured | 20 injured | ||||||

| ||||||

The Raid of Żejtun (Maltese: L-Aħħar Ħbit – The Last Attack) was the last major attack made by the Ottoman Empire against the island of Malta, which was then ruled by the Order of St. John. The attack took place in July 1614, when raiders pillaged the town of Żejtun and the surrounding area before being beaten back to their ships by the Order's cavalry and by the inhabitants of the south-eastern towns and villages.

Background

The Ottomans first attempted to take Malta in 1551, when they sacked Gozo but did not take over Malta. In 1565, they made a second attempt known as the Great Siege of Malta, but they were repelled after four months of fighting. The Ottomans stayed away from Malta following the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, but began to make incursions to the central Mediterranean once again at the end of the century. In 1598, 40 Ottoman vessels were sighted off Capo Passero in Sicily, triggering a general alarm in Malta. Similar emergencies occurred in 1603 and 1610. Due to this, the Order began preparing for an Ottoman attack. The obsolete Cittadella of Gozo was rebuilt, Valletta's water supply was secured by the building of the Wignacourt Aqueduct, and coastal watchtowers began to be built.[1]

Attack

Two hours before dawn on 6 July 1614, a considerable Turkish force of sixty ships (including 52 galleys) under the command of Khalil Pasha[2] tried to land at Marsaxlokk Bay, but were repelled by the artillery from the newly-constructed St. Lucian Tower. The fleet laid anchor at St Thomas Bay in Marsaskala, and managed to land 5000 to 6000 men unopposed.[1]

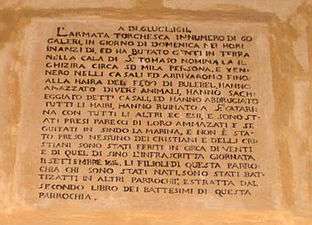

Some of the Ottomans went to attack St. Lucian Tower, while the rest of the force pillaged the village of Żejtun, which had been abandoned by its inhabitants after they heard about the attack. The Ottomans burnt the farms and fields of the area, and they also damaged the church of St Gregory's, then referred to as the parish church of St Catherine's. The attack is described in a commemorative plaque engraved close to the main altar of St Gregory's, which states that:

In the early hours of Sunday, July 6, 1614, a Turkish army landed from 60 galleys, disembarking six thousand men in the place called Ghizira in Saint Thomas’ creek. The Turks raided the nearby casali, arriving right up to the farmlands held under the feud of Bulebel. They sacked these townships, burnt farmland and did much damage to the main church of Saint Catherine’s and all the others. Many were caught and killed, and they were made to retire back to the quays. No Christian was captured, but twenty were injured in the attack. From that day until September 11, 1614, all those born in this parish had to be baptised elsewhere. Extracted from the second book of baptisms for this parish.

Upon hearing about the attack, the Order sent a cavalry regiment to attack the invaders, but they were almost defeated by the Ottomans. Meanwhile, a militia force of around 6000 to 8000 men was assembled, and it fought the Ottomans in a number of skirmishes lasting a couple of days. The Ottomans returned to their ships on 12 July, and they sailed to Mellieħa Bay to take on water before going to Tripoli on a punitive expedition against a local insurgent. The fleet then suppressed a Greek uprising in the southern Peloponnese before returning to Constantinople in November 1614.[1]

Consequences

The attack confirmed the need of coastal watchtowers, and the construction of a tower defending St. Thomas Bay was approved on 11 July 1614.[3] The new tower, however, could not communicate with St. Lucian Tower. In case of attack or the landing of enemy forces in either bay, some intermediate signalling station was needed to allow the despatch of reinforcements.

Following the attack, the Order added two transepts and a dome to the fifteenth century parish church of Saint Catherine's. A narrow passage with two small windows looking at the towers of these forts was built high up in the thickness of the transept walls.[4] The finding of human bones in a number of secret passages of this church was, for many years, linked with this attack.[5]

In 1658, the leader of the Żejtun contingent, Clemente Tabone, built a chapel dedicated to St Clement, in commemoration of the deliverance from the attack.[6] The chapel is believed to stand close to the location of the battle with the Turkish raiders.[7]

Gallery

-

St. Lucian Tower, which prevented the Ottomans from landing at Marsaxlokk Bay

-

St. Thomas Bay, where the Ottomans landed

-

Commemorative plaque of the raid at St Gregory's church

-

St. Thomas Tower, which was built soon after the attack to protect St. Thomas Bay

-

Chapel of St. Clement, built in 1658 to commemorate the deliverance from the attack

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Spiteri, Stephen C. (2013). "In Defence of the Coast (I) - The Bastioned Towers". Arx - International Journal of Military Architecture and Fortification (3): 42–43. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ E.J. Brill First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 4 page 889

- ↑ Ciantar 1772, pp. 316–317

- ↑ Hughes 1975, p. 122

- ↑ Fiona Vella (2012). "Find at St Gregory church still shrouded in mystery". Times of Malta.

- ↑ Vv Aa. 1955, p. 155

- ↑ "St. Clement's Chapel". Żejtun Local Council. 2012.

Bibliography

- Ciantar, G.A. (1772). Malta illustrata... accresciuta dal Cte G.A. Ciantar. Malta: Mallia. pp. 316–317.

- Hughes, Quentin (1975). Excursions into architecture. United Kingdom: St. Martin's Press. p. 122.

- Vv., Aa. (1955). Communicaciones Y Conclusiones Del Iii Congreso Internacional de Genealogia Y Heraldica. 1955. Spain: Ediciones Hidalguia. p. 155.