Progression (E7-A7-D7-G7)

Play

Play which often appears in the

bridge of

jazz standards.

[1] The V7/V/V/V - V7/V/V - V7/V - V7 [or V7/vi - V7/ii - V7/V - V7] leads back to C major (I)

Play

Play but is itself indefinite in key.

Ragtime progression's origin in

voice leading: II itself is the product of a 5-6 replacement over IV in IV-V-I. "Such a replacement originates purely in voice-leading, but," the

chord above IV (in C: F-A-D) is a first inversion II chord.

[2]  Play

Play

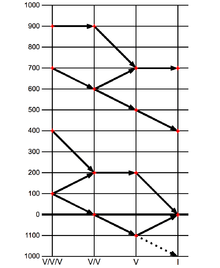

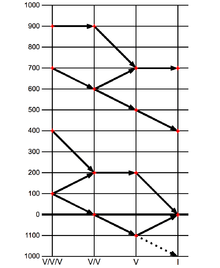

Movement in the ragtime progression. Note that the third and seventh descend to the seventh and third of the next chord by descending half-step, creating two chromatic lines.

The ragtime progression[3] is a chord progression characterized by a chain of secondary dominants, named for its popularity in the ragtime genre, despite being much older.[4] Also typical of parlour music, its use originated in classical music and later spread to American folk music.[5] Growing, "by a process of gradual accretion. First the dominant chord acquired its own dominant...This then acquired its dominant, which in turn acquired yet another dominant, giving":[6]

Or:[7][8]

| (V7/V/V/V) |

V7/V/V |

V7/V |

V7 |

I |

Or:[9][10]

In C major this is:

Most commonly found in its four chord version (thus the parentheses).  Play This may be perceived as a, "harder, bouncier sounding progression," than the diatonic vi-ii-V7-I, in C: Am-Dm-G7-C.[11][12]

Play This may be perceived as a, "harder, bouncier sounding progression," than the diatonic vi-ii-V7-I, in C: Am-Dm-G7-C.[11][12]  Play The three chord version (II-V-I) is, "related to the cadential progression IV-V-I...in which the V is tonicized and stabilized by means of II with a raised third."[2]

Play The three chord version (II-V-I) is, "related to the cadential progression IV-V-I...in which the V is tonicized and stabilized by means of II with a raised third."[2]

The progression is an example of centripetal harmony, harmony which leads to the tonic and an example of the circle progression, a progression along the circle of fourths. Though creating or featuring chromaticism, the bass (if the roots of the chords), and often the melody, are pentatonic.[6] (Major pentatonic on C: CDEGA) Contrastingly, Averill argues that the progression was used because of the potential if offered for chromatic pitch areas.[13]

Variations include the addition of minor seventh chords before the dominant seventh chords, creating overlapping temporary ii-V-I relationships[14] through ii-V-I substitution:

| Bm7-E7 |

Em7-A7 |

Am7-D7 |

Dm7-G7 |

C |

since Bm7-E7-A is a ii-V-I progression, as is Em7-A7-D and so on.  Play

Play

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. |

Examples of the use of the ragtime progression include the chorus of Howard & Emerson's "Hello! Ma Baby" (1899), the traditional "Keep On Truckin' Mama", Robert Johnson's "They're Red Hot" (1936), Arlo Guthrie's "Alice's Restaurant" (1967),[15] Bruce Channel's "Hey! Baby" (1962), The Rooftop Singers' "Walk Right In" (1963), James P. Johnson's "Charleston" (1923), Ray Henderson's "Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue" (1925),[12] Rev. Gary Davis's "Salty Dog",[16] Bernie and Pinkard's "Sweet Georgia Brown" (1925), the "Cujus animam" (mm.9-18) in Rossini's Stabat Mater, the beginning of Liszt's Liebesträume (1850),[6] Bob Carleton's "Ja-Da" (1918),[17] and Sonny Rollins's "Doxy" (1954).[18]

See also

Sources

- ↑ Boyd, Bill (1997). Jazz Chord Progressions, p.56. ISBN 0-7935-7038-7.

- 1 2 Jonas, Oswald (1982) Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker (1934: Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerks: Eine Einführung in Die Lehre Heinrich Schenkers), p.116. Trans. John Rothgeb. ISBN 0-582-28227-6.

- ↑ Fahey, John (1970). Charley Patton, p.45. London: Studio Vista. Cited in van der Merwe (1989).

- ↑ van der Merwe, Peter (2005). Roots of the Classical, p.496. ISBN 978-0-19-816647-4.

- ↑ van der Merwe, Peter (1989). Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music, p.321. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-316121-4.

- 1 2 3 Van der Merwe (2005), p.299.

- ↑ Warnock, Matthew. "Turnarounds: How to Turn One Chord into Four". Music Theory Lesson. jazzguitar.be. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ↑ Levine, Mark (1996). The jazz theory book. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 1-883217-04-0. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ↑ Averill, Gage (2003). Four Parts, No Waiting, p.162. ISBN 978-0-19-511672-4.

- ↑ Weissman, Dick (2005). Blues: The Basics, p.50. ISBN 978-0-415-97067-9.

- ↑ Scott, Richard J. (2003). Chord Progressions for Songwriters, p.428. ISBN 978-0-595-26384-4.

- 1 2 Davis, Kenneth (2006). The Piano Professor Easy Piano Study, p.105. ISBN 978-1-4303-0334-3. Same quote but gives the progression in E instead of C.

- ↑ Averill, Gage (2003). Four Parts, No Waiting: A Social History of American Barbershop Harmony, p.162. ISBN 978-0-19-511672-4.

- ↑ Boyd (1997), p.60.

- ↑ Scott (2003), p.429

- ↑ Grossman, Stefan (1998). Rev. Gary Davis/Blues Guitar, p.71. ISBN 978-0-8256-0152-1.

- ↑ Weissman, Dick (2001). Songwriting: The Words, the Music and the Money, p.59. ISBN 9780634011603. and Weissman, Dick (1085). Basic Chord Progressions: Handy Guide, p.28. ISBN 9780882844008.

- ↑ Fox, Charles; McCarthy, Albert (1960). Jazz on record: a critical guide to the first 50 years, 1917-1967. Hanover Books. p. 62.

Further reading

- Averill, Gage (2003). Four Parts, No Waiting, p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-511672-4.

|

|---|

| | Terminology | |

|---|

| By number

of chords | |

|---|

| | By name | |

|---|

| | Related | |

|---|

| |

|

chord above IV (in C: F-A-D) is a first inversion II chord.[2]

chord above IV (in C: F-A-D) is a first inversion II chord.[2]

![]() Play This may be perceived as a, "harder, bouncier sounding progression," than the diatonic vi-ii-V7-I, in C: Am-Dm-G7-C.[11][12]

Play This may be perceived as a, "harder, bouncier sounding progression," than the diatonic vi-ii-V7-I, in C: Am-Dm-G7-C.[11][12] ![]() Play The three chord version (II-V-I) is, "related to the cadential progression IV-V-I...in which the V is tonicized and stabilized by means of II with a raised third."[2]

Play The three chord version (II-V-I) is, "related to the cadential progression IV-V-I...in which the V is tonicized and stabilized by means of II with a raised third."[2]![]() Play

Play