Radon transform

In mathematics, the Radon transform in two dimensions, named after the Austrian mathematician Johann Radon, is the integral transform consisting of the integral of a function over straight lines. The transform was introduced in 1917 by Radon,[1] who also provided a formula for the inverse transform. Radon further included formulas for the transform in three dimensions, in which the integral is taken over planes. It was later generalised to higher-dimensional Euclidean spaces, and more broadly in the context of integral geometry. The complex analog of the Radon transform is known as the Penrose transform.

The Radon transform is widely applicable to tomography, the creation of an image from the projection data associated with cross-sectional scans of an object. If a function ƒ represents an unknown density, then the Radon transform represents the projection data obtained as the output of a tomographic scan. Hence the inverse of the Radon transform can be used to reconstruct the original density from the projection data, and thus it forms the mathematical underpinning for tomographic reconstruction, also known as image reconstruction. The Radon transform data is often called a sinogram because the Radon transform of a Dirac delta function is a distribution supported on the graph of a sine wave. Consequently the Radon transform of a number of small objects appears graphically as a number of blurred sine waves with different amplitudes and phases. The Radon transform is useful in computed axial tomography (CAT scan), barcode scanners, electron microscopy of macromolecular assemblies like viruses and protein complexes, reflection seismology and in the solution of hyperbolic partial differential equations.

Definition

Let ƒ(x) = ƒ(x,y) be a compactly supported continuous function on R2. The Radon transform, Rƒ, is a function defined on the space of straight lines L in R2 by the line integral along each such line:

Concretely, the parametrization of any straight line L with respect to arc length z can always be written

where s is the distance of L from the origin and  is the angle the normal vector to L makes with the x axis. It follows that the quantities (α,s) can be considered as coordinates on the space of all lines in R2, and the Radon transform can be expressed in these coordinates by

is the angle the normal vector to L makes with the x axis. It follows that the quantities (α,s) can be considered as coordinates on the space of all lines in R2, and the Radon transform can be expressed in these coordinates by

More generally, in the n-dimensional Euclidean space Rn, the Radon transform of a compactly supported continuous function ƒ is a function Rƒ on the space Σn of all hyperplanes in Rn. It is defined by

for ξ ∈Σn, where the integral is taken with respect to the natural hypersurface measure, dσ (generalizing the |dx| term from the 2-dimensional case). Observe that any element of Σn is characterized as the solution locus of an equation

where α ∈ Sn−1 is a unit vector and s ∈ R. Thus the n-dimensional Radon transform may be rewritten as a function on Sn−1×R via

It is also possible to generalize the Radon transform still further by integrating instead over k-dimensional affine subspaces of Rn. The X-ray transform is the most widely used special case of this construction, and is obtained by integrating over straight lines.

Generalized Radon Transform

Let s ∈ R, φ ∈[0,2π]. We let μ(φ,x) be a smooth function, 2π periodic in φ defined on Rx R 2 . Then, the generalized radon transform is defined as follows.

Where  is the arc length measure on the line L(φ, s). Note, that the transform integrates the weighted function f(x) along the lines L(φ,s).

is the arc length measure on the line L(φ, s). Note, that the transform integrates the weighted function f(x) along the lines L(φ,s).

Relationship with the Fourier transform

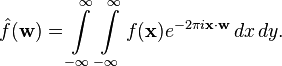

The Radon transform is closely related to the Fourier transform. For a function of one variable the Fourier transform is defined by

and for a function of a 2-vector  ,

,

For convenience define = R[f](\alpha,s)](../I/m/2036c7eba84eca0477c181986af14bbb.png) as it is only meaningful to take the Fourier transform in the

as it is only meaningful to take the Fourier transform in the  variable. The Fourier slice theorem then states

variable. The Fourier slice theorem then states

where

Thus the two-dimensional Fourier transform of the initial function is the one variable Fourier transform of the Radon transform of that function. More generally, one has the result valid in n dimensions

Indeed, the result follows at once by computing the two variable Fourier integral along appropriate slices:

An application of the Fourier inversion formula also gives an explicit inversion formula for the Radon transform, and thus shows that it is invertible on suitably chosen spaces of functions. However this form is not particularly useful for numerical inversion, and faster discrete inversion methods exist.

Dual transform

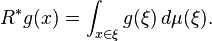

The dual Radon transform is a kind of adjoint to the Radon transform. Beginning with a function g on the space Σn, the dual Radon transform is the function R∗g on Rn defined by

The integral here is taken over the set of all lines incident with the point x ∈ Rn, and the measure dμ is the unique probability measure on the set  invariant under rotations about the point x.

invariant under rotations about the point x.

Concretely, for the two-dimensional Radon transform, the dual transform is given by

In the context of image processing, the dual transform is commonly called backprojection[2] as it takes a function defined on each line in the plane and 'smears' or projects it back over the line to produce an image. Computationally efficient inversion formulas reconstruct the image from the points where the back-projection lines meet.

Intertwining property

Let Δ denote the Laplacian on Rn:

This is a natural rotationally invariant second-order differential operator. On Σn, the "radial" second derivative

is also rotationally invariant. The Radon transform and its dual are intertwining operators for these two differential operators in the sense that[3]

Inversion formulas

Explicit and computationally efficient inversion formulas for the Radon transform and its dual are available. The Radon transform in n dimensions can be inverted by the formula[4]

where

and the power of the Laplacian (−Δ)(n−1)/2 is defined as a pseudodifferential operator if necessary by the Fourier transform

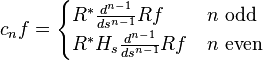

For computational purposes, the power of the Laplacian is commuted with the dual transform R* to give[5]

where Hs is the Hilbert transform with respect to the s variable. In two dimensions, the operator Hsd/ds appears in image processing as a ramp filter.[6] One can prove directly from the Fourier slice theorem and change of variables for integration that for a compactly supported continuous function ƒ of two variables

Thus in an image processing context the original image ƒ can be recovered from the 'sinogram' data Rƒ by applying a ramp filter (in the  variable) and then back-projecting. As the filtering step can be performed efficiently (for example using digital signal processing techniques) and the back projection step is simply an accumulation of values in the pixels of the image, this results in a highly efficient, and hence widely used, algorithm.

variable) and then back-projecting. As the filtering step can be performed efficiently (for example using digital signal processing techniques) and the back projection step is simply an accumulation of values in the pixels of the image, this results in a highly efficient, and hence widely used, algorithm.

Explicitly, the inversion formula obtained by the latter method is[2]

if n is odd, and

if n is even.

The dual transform can also be inverted by an analogous formula:

See also

- Deconvolution

- Funk transform

- The Hough transform, when written in a continuous form, is very similar, if not equivalent, to the Radon transform.[7]

- Cauchy-Crofton theorem is a closely related formula for computing the length of curves in space.

- Fourier transform

Notes

- ↑ Radon 1917.

- 1 2 Roerdink 2001

- ↑ Helgason 1984, Lemma I.2.1

- ↑ Helgason 1984, Theorem I.2.13

- ↑ Helgason 1984, Theorem I.2.16

- ↑ Filtered Back Projection

- ↑ http://www.tnw.tudelft.nl/live/pagina.jsp?id=45028650-24bd-4b30-9ada-b11aaca457c0&lang=en&binary=/doc/mvanginkel_radonandhough_tr2004.pdf

References

- Deans, Stanley R. (1983), The Radon Transform and Some of Its Applications, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Helgason, Sigurdur (2008), Geometric analysis on symmetric spaces, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs 39 (2nd ed.), Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-4530-1, MR 2463854.

- Helgason, Sigurdur (1984), Groups and Geometric Analysis: Integral Geometry, Invariant Differential Operators, and Spherical Functions, Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-338301-3.

- Herman, Gabor T. (2009), Fundamentals of Computerized Tomography: Image Reconstruction from Projections (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-1-85233-617-2.

- Minlos, R.A. (2001), "Radon transform", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4.

- Natterer, Frank, The Mathematics of Computerized Tomography, Classics in Applied Mathematics 32, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, ISBN 0-89871-493-1

- Natterer, Frank; Wübbeling, Frank, Mathematical Methods in Image Reconstruction, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, ISBN 0-89871-472-9.

- Radon, Johann (1917), "Über die Bestimmung von Funktionen durch ihre Integralwerte längs gewisser Mannigfaltigkeiten", Berichte über die Verhandlungen der Königlich-Sächsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig, Mathematisch-Physische Klasse [Reports on the proceedings of the Royal Saxonian Academy of Sciences at Leipzig, mathematical and physical section] (Leipzig: Teubner) (69): 262–277; Translation: Radon, J.; Parks, P.C. (translator) (1986), "On the determination of functions from their integral values along certain manifolds", IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 5 (4): 170–176, doi:10.1109/TMI.1986.4307775, PMID 18244009.

- Roerdink, J.B.T.M. (2001), "Tomography", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Radon transform", MathWorld..

![\widehat{R_{\alpha}[f]}(\sigma)=\hat{f}(\sigma\mathbf{n}(\alpha))](../I/m/3902aec33408cfb1e924e29dfb66f141.png)

= |2\pi\xi|^{n-1}\mathcal{F}\phi(\xi).](../I/m/99557f14584ec15143012013cd6f7a67.png)