Parabolic trajectory

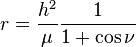

In astrodynamics or celestial mechanics a parabolic trajectory is a Kepler orbit with the eccentricity equal to 1. When moving away from the source it is called an escape orbit, otherwise a capture orbit. It is also sometimes referred to as a C3 = 0 orbit (see Characteristic energy).

Under standard assumptions a body traveling along an escape orbit will coast along a parabolic trajectory to infinity, with velocity relative to the central body tending to zero, and therefore will never return. Parabolic trajectories are minimum-energy escape trajectories, separating positive-energy hyperbolic trajectories from negative-energy elliptic orbits.

Velocity

Under standard assumptions the orbital velocity ( ) of a body travelling along parabolic trajectory can be computed as:

) of a body travelling along parabolic trajectory can be computed as:

where:

is the radial distance of orbiting body from central body,

is the radial distance of orbiting body from central body, is the standard gravitational parameter.

is the standard gravitational parameter.

At any position the orbiting body has the escape velocity for that position.

If the body has the escape velocity with respect to the Earth, this is not enough to escape the Solar System, so near the Earth the orbit resembles a parabola, but further away it bends into an elliptical orbit around the Sun.

This velocity ( ) is closely related to the orbital velocity of a body in a circular orbit of the radius equal to the radial position of orbiting body on the parabolic trajectory:

) is closely related to the orbital velocity of a body in a circular orbit of the radius equal to the radial position of orbiting body on the parabolic trajectory:

where:

is orbital velocity of a body in circular orbit.

is orbital velocity of a body in circular orbit.

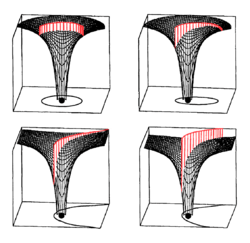

Equation of motion

Under standard assumptions, for a body moving along this kind of trajectory an orbital equation becomes:

where:

is radial distance of orbiting body from central body,

is radial distance of orbiting body from central body, is specific angular momentum of the orbiting body,

is specific angular momentum of the orbiting body, is a true anomaly of the orbiting body,

is a true anomaly of the orbiting body, is the standard gravitational parameter.

is the standard gravitational parameter.

Energy

Under standard assumptions, specific orbital energy ( ) of parabolic trajectory is zero, so the orbital energy conservation equation for this trajectory takes form:

) of parabolic trajectory is zero, so the orbital energy conservation equation for this trajectory takes form:

where:

is orbital velocity of orbiting body,

is orbital velocity of orbiting body, is radial distance of orbiting body from central body,

is radial distance of orbiting body from central body, is the standard gravitational parameter.

is the standard gravitational parameter.

This is entirely equivalent to the characteristic energy (square of the speed at infinity) being 0:

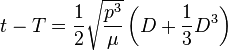

Barker's equation

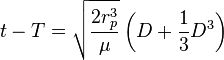

Barker's equation relates the time of flight to the true anomaly of a parabolic trajectory.[1]

Where:

- D = tan(ν/2), ν is the true anomaly of the orbit

- t is the current time in seconds

- T is the time of periapsis passage in seconds

- μ is the standard gravitational parameter

- p is the semi-latus rectum of the trajectory ( p = h2/μ )

More generally, the time between any two points on an orbit is

Alternately, the equation can be expressed in terms of periapsis distance, in a parabolic orbit rp = p/2:

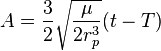

Unlike Kepler's equation, which is used to solve for true anomalies in elliptical and hyperbolic trajectories, the true anomaly in Barker's equation can be solved directly for t. If the following substitutions are made[2]

![B = \sqrt[3]{A + \sqrt{A^{2}+1}}](../I/m/f61289c01440abe0912dd6d1f825c375.png)

then

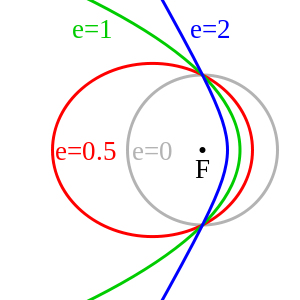

Radial parabolic trajectory

A radial parabolic trajectory is a non-periodic trajectory on a straight line where the relative velocity of the two objects is always the escape velocity. There are two cases: the bodies move away from each other or towards each other.

There is a rather simple expression for the position as function of time:

where

- μ is the standard gravitational parameter

-

corresponds to the extrapolated time of the fictitious starting or ending at the center of the central body.

corresponds to the extrapolated time of the fictitious starting or ending at the center of the central body.

At any time the average speed from  is 1.5 times the current speed, i.e. 1.5 times the local escape velocity.

is 1.5 times the current speed, i.e. 1.5 times the local escape velocity.

To have  at the surface, apply a time shift; for the Earth (and any other spherically symmetric body with the same average density) as central body this time shift is 6 minutes and 20 seconds; seven of these periods later the height above the surface is three times the radius, etc.

at the surface, apply a time shift; for the Earth (and any other spherically symmetric body with the same average density) as central body this time shift is 6 minutes and 20 seconds; seven of these periods later the height above the surface is three times the radius, etc.

See also

References

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||