Cobia

| Cobia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Rachycentridae |

| Genus: | Rachycentron Kaup, 1826 |

| Species: | R. canadum |

| Binomial name | |

| Rachycentron canadum (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

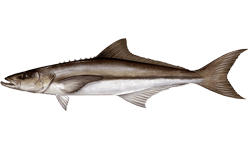

The cobia (Rachycentron canadum) is a species of perciform marine fish, the only representative of the genus Rachycentron and the family Rachycentridae. Other common names include black kingfish, black salmon, ling, lemonfish, crabeater, prodigal son, black bonito, and aruan tasek.

Description

Attaining a maximum length of 2 m (78 in) and maximum weight of 78 kg (172 lb), the cobia has an elongated fusiform (spindle-shaped) body and a broad, flattened head. The eyes are small and the lower jaw projects slightly past the upper. Fibrous villiform teeth line the jaws, the tongue, and the roof of the mouth. The body of the fish is smooth with small scales. It is dark brown in color, grading to white on the belly with two darker brown horizontal bands on the flanks. The stripes are more prominent during spawning, when they darken and the background color lightens.

The large pectoral fins are normally carried horizontally, perhaps helping the fish attain the profile of a shark. The first dorsal fin has six to 9 independent, short, stout, sharp spines. The family name Rachycentridae, from the Greek words rhachis ("spine") and kentron ("sting"), was inspired by these dorsal spines. The mature cobia has a forked, slightly lunated tail, which is usually dark brown. The fish lacks a swim bladder. The juvenile cobia is patterned with conspicuous bands of black and white and has a rounded tail. The largest cobia taken on rod and reel came from Shark Bay, Australia, and weighed 60 kg (135 lb).

Similar species

The cobia resembles its close relatives, the remoras of the family Echeneidae. It lacks the remora's dorsal sucker and has a stouter body.

Distribution and habitat

The cobia is normally solitary except for annual spawning aggregations, and sometimes it will congregate at reefs, wrecks, harbours, buoys, and other structural oases. It is pelagic, but it may enter estuaries and mangroves in search of prey.

It is found in warm-temperate to tropical waters of the West and East Atlantic Ocean, throughout the Caribbean, and in the Indo-Pacific off India, Australia and Japan.[1] It is eurythermal, tolerating a wide range of temperatures, from 1.6 to 32.2 °C. It is also euryhaline, living at salinities of 5 to 44.5 ppt.[2]

Ecology

The cobia feeds primarily on crabs, squid, and fish. It will follow larger animals such as sharks, turtles, and manta rays to scavenge. It is a very curious fish, showing little fear of boats.

The predators of the cobia are not well documented, but the mahi-mahi (Coryphaena hippurus) is known to feed on juveniles and the shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus) eats the adult.

The cobia is frequently parasitized by nematodes, trematodes, cestodes, copepods, and acanthocephalans.

Life history

The cobia is a pelagic spawner, releasing many tiny (1.2 mm), buoyant eggs into the water, where they become part of the plankton. The eggs float freely with the currents until hatching. The larvae are also planktonic, being more or less helpless during their first week until the eyes and mouths develop. The male matures at two years and the female at three years. Both sexes lead moderately long lives of 15 years or more. Breeding activity takes place diurnally from April to September in large offshore congregations, where the female is capable of spawning up to 30 times during the season.[3]

Migration

The cobia makes seasonal migrations. It winters in the Gulf of Mexico, then moves north as far as Massachusetts for the summer, passing Florida around March. [4]

Human uses

The cobia is sold commercially and commands a relatively high price for its firm texture and excellent flavor. However, no designated wild fishery exists because it is a solitary species. It has been farmed in aquaculture. The flesh is usually sold fresh. It is typically served in the form of grilled or poached fillets. Chefs Jamie Oliver and Mario Batali each cooked several dishes made with cobia in the "Battle Cobia" episode of the Food Network program Iron Chef America, which first aired in January, 2008. Thomas Keller's restaurant, The French Laundry, has offered cobia on its tasting menu.[5]

Aquaculture

This fish is considered to be one of the most suitable candidates for warm, open-water marine fish aquaculture in the world.[6][7] Its rapid growth rate and the high quality of the flesh could make it one of the most important marine fish for future aquaculture production.[8]

Currently, the cobia is being cultured in nurseries and offshore grow-out cages in parts of Asia, the United States, Mexico, and Panama. In Taiwan, cobia of 100 to 600 g are cultured for 1.0 to 1.5 years until they reach 6 to 8 kg. They are then exported to Japan, China, North America, and Europe. Around 80% of marine cages in Taiwan are devoted to cobia culture.[7] In 2004, the FAO reported that 80.6% of the world's cobia production was in China and Taiwan.[9] Vietnam is the third-largest producer, yielding 1,500 tonnes in 2008.[7] Following the success of cobia aquaculture in Taiwan, emerging technology is being used to demonstrate the viability of hatchery-reared cobia in collaboration with the private sector at exposed offshore sites in Puerto Rico and the Bahamas, and the largest open ocean farm in the world is run by a company called Open Blue off the coast of Panama.[10]

Greater depths, stronger currents, and distance from shore all act to reduce environmental impacts often associated with finfish aquaculture. Offshore cage systems could become a more environmentally sustainable method for commercial marine fish aquaculture.[11] However, some problems still exist in cobia culture, including high mortality due to stress during transfer from nursery tanks or inshore cages to the offshore grow-out cages, as well as disease.[7]

Timeline

References

- ↑ Ditty, J. G. & Shaw, R. F. 1992. Larval development, distribution, and ecology of cobia Rachycentron canadum (Family: Rachycentridae) in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Fishery Bulletin, 90:668-677

- ↑ Resley, M. J., Webb, K. A. & Holt, G. J. 2006. Growth and survival of juvenile cobia Rachycentron canadum cultured at different salinities in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquaculture, 253:398-407.

- ↑ Brown-Peterson, N. J., Overstreet, R. M., Lotz, J. M. 2001. Reproductive biology of cobia, Rachycentron canadum, from coastal waters of the southern United States. Fish. Bull. 99:15-28

- ↑ http://www.onthewater.com/reader-report-cape-cod-cobia/

- ↑ French Laundry menu, September 2011

- ↑ Kaiser, J.B. & Holt, G.J. 2004. Cobia: a new species for aquaculture in the US. World Aquaculture, 35:12-14.

- 1 2 3 4 Liao, I.C., Huang, T.S., Tsai, W.S., Hsueh, C.M., Chang, S.L. & Leano, E.M. 2004. Cobia culture in Taiwan: current status and problems. Aquaculture, 237:155-165.

- ↑ Nhu, V. C., Nguyen, H. Q., Le, T. L., Tran, M. T., Sorgeloos, P., Dierckens, K., Reinertsen H., Kjorsvik, E. & Svennevig, N. 2011. Cobia Rachycentron canadum aquaculture in Vietnam: recent developments and prospects. Aquaculture 315:20-25.

- ↑ FAO

- ↑ Benetti, D. D., et al. 2007. Aquaculture of cobia (Rachycentron canadum) in the Americas and the Caribbean. RSMAS, p. 1-21.

- ↑ Benetti, D.D., et al. 2003. Advances in hatchery and growout technology of marine finfish candidate species for offshore aquaculture in the Caribbean. Proceedings of the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute, 54:475-487.

Other references

- "Rachycentron canadum". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 30 January 2006.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2005). "Rachycentron canadum" in FishBase. 10 2005 version.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2005). "Rachycentridae" in FishBase. May 2005 version.

- Greenberg, Idaz. Guide to Corals & Fishes of Florida, the Bahamas and the Caribbean. Seahawk Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-913008-08-7.

- Applegarth, Allen. Florida Inshore Angler. p. 36.

- Cobia NOAA FishWatch. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- {{http://www.fieldandstream.com/blogs/lateral-line/2014/01/now-my-friends-serious-cobia?src=SOC&dom=fb}}