Qutb complex

Coordinates: 28°31′28″N 77°11′08″E / 28.524382°N 77.185430°E

| Qutb Minar and its Monuments, Delhi | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| |

| Type | Cultural Place |

| Criteria | iv |

| Reference | 233 |

| UNESCO region | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1993 (17th Session) |

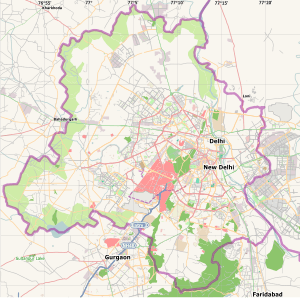

Location of Qutb complex in India New Delhi. | |

The Qutb complex (Hindi: कुत्ब , Urdu: قطب), also spelled Qutab (Hindi: क़ुतब, Urdu: قطب) or Qutub (Hindi: क़ुतुब, Urdu: قطب), is an array of monuments and buildings at Mehrauli in Delhi, India. The best-known structure in the complex is the Qutb Minar, built to honor the Sufi saint Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki. Its foundation was laid by Qutb-ud-din Aibak, who later became the first Sultan of Delhi of the Mamluk dynasty. The Minar was added upon by his successor Iltutmish (a.k.a. Altamash), and much later by Firoz Shah Tughlaq, a Sultan of Delhi from the Tughlaq dynasty in 1368 AD. The Qubbat-ul-Islam Mosque (or, Dome of Islam), later corrupted into Quwwat-ul Islam[1] stands next to the Qutb Minar.[2][3][4][5] It was built on the ruins of Lal Kot Fort (built by Anangpal, the Tomar Gurjar ruler, in 739 CE) and Qila-Rai-Pithora (the Gurjar king Prithviraj Chauhan's city), whom Ghori's Afghan armies had earlier defeated and killed in the Second Battle of Tarain.[6]

The complex was added to by many subsequent rulers, including the Tughlaqs, Ala ud din Khilji and the British.[7] Apart from the Qutb Minar and the Quwwat ul-Islam Mosque, other structures in the complex include the Alai Gate, the Alai Minar, the Iron pillar, the ruins of several earlier Jain temples, and the tombs of Iltutmish, Alauddin Khilji and Imam Zamin.[3]

Today, the adjoining area spread over with a host of old monuments, including Balban's tomb, has been developed by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) as the Mehrauli Archaeological Park, and INTACH has restored some 40 monuments in the Park.[8] It is also the venue of the annual 'Qutub Festival', held in November–December, where artists, musicians and dancers perform over three days. The Qutb Minar complex, which drew 3.9 million visitors in 2006, was India's most visited monument that year, ahead of the Taj Mahal (with 2.5 million visitors).[9]

Alai Darwaza

The Alai Darwaza is the main gateway from southern side of the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque.[10] It was built by the second Khilji Sultan of Delhi, Ala-ud-din Khilji in 1311 AD, who also added a court to the pillared to the eastern side. The domed gateway is decorated with red sandstone and inlaid white marble decorations, inscriptions in Naskh script, latticed stone screens and showcases the remarkable craftsmanship of the Turkish artisans who worked on it. This is the first building in India to employ Islamic architecture principles in its construction and ornamentation.[3]

The Slave dynasty did not employ true Islamic architecture styles and used false domes and false arches. This makes the Alai Darwaza, the earliest example of first true arches and true domes in India.[11] It is considered to be one of the most important buildings built in the Delhi sultanate period. With its pointed arches and spearhead of fringes, identified as lotus buds, it adds grace to the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque to which it served as an entrance.

Qutb Minar

The Qutb Minar is the tallest brick minaret in the world, inspired by the Minaret of Jam in Afghanistan, it is an important example of early Afghan architecture, which later evolved into Indo-Islamic Architecture. The Qutb Minar is 72.5 metres (239 ft) high, has five distinct storeys, each marked by a projecting balcony carried on muqarnas corbel and tapers from a diameter 14.3 metres at the base to 2.7 metres at the top, which is 379 steps away. It is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site along with surrounding buildings and monuments.[12]

Built as a Victory Tower, to celebrate the victory of Mohammed Ghori over the Rajput king, Prithviraj Chauhan, in 1192 AD, by his then viceroy, Qutbuddin Aibak, later the first Sultan of Mamluk dynasty. Its construction also marked the beginning of Muslim rule in India. Even today the Qutb remains one of the most important "Towers of Victory" in the Islamic world. Aibak however, could only build the first storey, for this reason the lower storey is replete with eulogies to Mohammed Ghori.[13] The next three floors were added by his son-in-law and successor, Iltutmish. The minar was first struck by lightning in 1368 AD, which knocked off its top storey, after that it was replaced by the existing two floors by Firoz Shah Tughlaq, a later Sultan of Delhi 1351 to 1388, and faced with white marble and sandstone enhancing the distinctive variegated look of the minar, as seen in lower three storeys. Thus the structure displays a marked variation in architectural styles from Aibak to that of Tughlaq dynasty.[14] The inside has intricate carvings of the verses from the Quran.

The minar made with numerous superimposed flanged and cylindrical shafts in the interior, and fluted columns on the exterior, which have a 40 cm thick veneer of red and buff coloured sandstone; all surrounded by bands of intricate carving in Kufic style of Islamic calligraphy, giving the minar the appearance of bundled reeds.[15] It stands just outside the Quwwatul mosque, and an Arabic inscription suggests that it might have been built to serve as a place for the muezzin, to call the faithfuls for namaz.[16][17] Also marking a progression in era, is the appearance of inscriptions in a bold and cursive Thuluth script of calligraphy on the Qutb Minar, distinguished by strokes that thicken on the top, as compared to Kufic in earlier part of the construction.[18]

Inscriptions also indicate further repairs by Sultan Sikander Lodi in 1503, when it was struck by lightning once again. In 1802, the cupola on the top was thrown down and the whole pillar was damaged by an earthquake. It was repaired by Major R. Smith of the Royal Engineers who restored the Qutub Minar in 1823 replacing the cupola with a Bengali-style chhatri which was later removed by Governor General, Lord Hardinge in 1848, as it looked out of place, and now stands in the outer lawns of the complex, popularly known as Smith's Folly.[2][16][19][20]

After an accident involving school children, entry to the Qutub Minar is closed to public since 1981, while Qutub archaeological area remains open for public.[21] In 2004, Seismic monitors were installed on the minar, which revealed in 2005 Delhi earthquake, no damage or substantial record of shakes. The reason for this has been cited as the use of lime mortar and rubble masonry which absorbs the tremors; it is also built on rocky soil, which further protects it during earthquakes.[19]

Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque

Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque(Arabic: قوة الإسلام ) (might of Islam) (also known as the Qutub Mosque or the Great Mosque of Delhi) was built by Qutb-ud-din Aibak, founder of the Mamluk or Slave dynasty.[22] It was the first mosque built in Delhi after the Islamic conquest of India and the oldest surviving example of Ghurids architecture in Indian subcontinent.[23] The construction of this Jami Masjid (Friday Mosque), started in the year 1193 AD, when Aibak was the commander of Muhammad Ghori's garrison that occupied Delhi. The Qutub Minar was built simultaneously with the mosque but appears to be a stand-alone structure, built as the 'Minar of Jami Masjid', for the muezzin to perform adhan, call for prayer, and also as a qutub, an Axis or Pole of Islam.[24] It is reminiscent in style and design of the Adhai-din-ka Jhonpra or Ajmer mosque at Ajmer, Rajasthan, also built by Aibak during the same time, also constructed by demolishing earlier temples and a Sanskrit school, at the site.[25]

According to a Persian inscription still on the inner eastern gateway, the mosque was built by the parts taken by destruction of twenty-seven Hindu and Jain temples[3][4][5] built previously during Tomars and Prithvi Raj Chauhan, and leaving certain parts of the temple outside the mosque proper.[26] Historical records compiled by Muslim historian Maulana Hakim Saiyid Abdul Hai attest to the iconoclasm of Qutb-ud-din Aibak. This pattern of iconoclasm was common during his reign, although an argument goes that such iconoclasm was motivated more by politics than by religion.[27]

However, many historians were unanimous regarding the fact that Qutb ud-Din Aibaq like many other Muslim rulers, had a pathological bigotry and distaste towards henotheistic values, and intolerance on cultures considered anathema in Islamic dogma, which had impelled him to vandalise those historic monuments. [28]

The mosque is built on a raised and paved courtyard, measuring 141 ft (43 m). X 105 ft (32 m), surrounded by pillared cloisters added by Iltutmish between 1210 and 1220 AD. The stone screen between prayer hall and the courtyard, stood 16 mt at its highest was added in 1196 AD, the corbelled arches had Arabic inscriptions and motifs.[2] Entrances to the courtyard, also uses ornate mandap dome from temples, whose pillars are used extensively throughout the edifice, and in the sanctuary beyond the tall arched screens. What survives today of the sanctuary on the western side are the arched screens in between, which once led to a series of aisles with low-domed ceilings for worshippers.[23] Expansion of the mosque continued after the death of Qutb. Qutbuddin's successor Iltutmish, extended the original prayer hall screen by three more arches. By the time of Iltutmish, the Mamluk empire had stabilised enough that the Sultan could replace most of his conscripted Hindu masons with Muslims. This explains why the arches added under Iltutmish are stylistically more Islamic than the ones erected under Qutb's rule, also because the material used wasn't from demolished temples. Some additions to the mosque were also done by Alauddin Khilji, including the Alai Darwaza, the formal entrance to the mosque in red sandstone and white marble, and a court to the east of the mosque in 1300 AD.

The mosque is in ruins today but indigenous corbelled arches, floral motifs, and geometric patterns can be seen among the Islamic architectural structures.[29] To the west of the Quwwat ul-Islam mosque is the tomb of Iltutmish which was built by the monarch in 1235.

Iron pillar

The iron pillar is one of the world’s foremost metallurgical curiosities. The pillar, 7.21-metre high and weighing more than six tonnes, was originally erected by Chandragupta II Vikramaditya (375–414 AD) in front of a Vishnu Temple complex at Udayagiri around 402 AD, and later shifted by Anangpal in 10th century CE from Udaygiri to its present location. Anangpal built a Vishnu Temple here and wanted this pillar to be a part of that temple.

The estimated weight of the decorative bell of the pillar is 646 kg while the main body weighs 5,865 kg, thus making the entire pillar weigh 6,511 kg.[30] The pillar bears an inscription in Sanskrit in Brahmi script dating 4th century AD, which indicates that the pillar was set up as a Vishnudhvaja, standard of god, on the hill known as Vishnupada in memory of a mighty king named Chandra, believed to Chandragupta II. A deep socket on the top of this ornate capital suggests that probably an image of Garuda was fixed into it, as common in such flagpoles.[31]

Tombs

Tomb of Iltutmish

The tomb of the Delhi Sultanate ruler, Iltutmish, the second Sultan of Delhi (r. 1211–1236 AD), built 1235 CE, is also part of the Qutb Minar Complex in Mehrauli, New Delhi. The central chamber is a 9 mt. sq. and has squinches, suggesting the existence of a dome, which has since collapsed. The main cenotaph, in white marble, is placed on a raised platform in the centre of the chamber. The facade is known for its ornate carving, both at the entrance and the interior walls. The interior west wall has a prayer niche (mihrab) decorated with marble, and a rich amalgamation of Hindu motives into Islamic architecture, such as bell-and-chain, tassel, lotus, diamond emblems.[2]

In 1914, during excavations by Archaeological Survey of India's (ASI) Gordon Sanderson, the grave chamber was discovered. From the north of the tomb 20 steps lead down to the actual burial vault.[32]

Ala-ud-din Khilji's tomb and madarsa

At the back of the complex, southwest of the mosque, stands an L-shaped construction, consisting of Alauddin Khilji's tomb dating ca 1316 AD, and a madarsa, an Islamic seminary built by him. Khilji was the second Sultan of Delhi from Khilji dynasty, who ruled from 1296 to 1316 AD.[33]

The central room of the building, which has his tomb, has now lost its dome, though many rooms of the seminary or college are intact, and since been restored. There were two small chambers connected to the tomb by passages on either side. Fergusson in his book suggested the existence, to the west of the tomb, of seven rooms, two of which had domes and windows. The remains of the tomb building suggest that there was an open courtyard on the south and west sides of the tomb building, and that one room in the north served as an entrance.[34]

It was the first example in India, of a tomb standing alongside a madarsa.[2] Nearby stands the Alai Minar, an ambitious tower, he started constructing to rival the Qutub Minar, though he died when only its first storey was built and its construction abandoned thereafter. It now stands, north of the mosque.

The tomb is in a very dilapidated condition. It is believed that Ala-ud-din's body was brought to the complex from Siri and buried in front of the mosque, which formed part of the madrasa adjoining the tomb. Firoz Shah Tughluq, who undertook repairs of the tomb complex, mentioned a mosque within the madrasa.[35]

Alai Minar

Alauddin Khilji started building the Alai Minar, after he had doubled the size of Quwwat ul-Islam mosque. He conceived this tower to be two times higher than Qutb Minar in proportion with the enlarged mosque.[36] The construction was however abandoned, just after the completion of the 24.5-metre-high (80 ft) first-story core; soon after death of Ala-ud-din in 1316, and never taken up by his successors of Khilji dynasty. The first story of the Alai Minar, a giant rubble masonry core, still stands today, which was evidently intended to be covered with dressed stone later on. Noted Sufi poet and saint of his times, Amir Khusro in his work, Tarikh-i-Alai, mentions Ala-ud-din's intentions to extend the mosque and also constructing another minar.[37]

Other monuments

A short distance west of the enclosure, in Mehrauli village, is the Tomb of Adham Khan who, according to legend drove the beautiful Hindu singer Roopmati to suicide following the capture of Mandu in Madhya Pradesh. When Akbar became displeased with him he ended up being heaved off a terrace in the Agra Fort. Several archaeological monuments dot the Mehrauli Archaeological Park, including the Balban's tomb, Jamali Kamali mosque and tomb.

There are some summer palaces in the area: the Zafar Mahal, the Jahaz Mahal next to Hauz-i-Shamsi lake, and the tombs of the later Mughal kings of Delhi, inside a royal enclosure near the dargah shrine of Sufi saint, Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki. Here an empty space between two of the tombs, sargah, was intended for the last king of Delhi, who died in exile in Rangoon, Burma, in 1862, following his implication in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Also standing nearby is the Moti Masjid mosque in white marble.The ruins of the alai minar are currently in the qutb complex.

Gallery

-

A map of the Qutb complex (click to see legend)

-

Statues from the destroyed Jain temples

-

Tomb of Imam Zamin, Qutub Minar Complex

-

Plaque at Qutub Minar.

-

Another view of Qutb Minar, with a Jain temple reused pillar in view

-

Upper storeys of Qutb Minar, in white marble and sandstone

-

Interior of Alai Darwaza, resembling Timber ornamentation, Qutb complex

-

Tomb of Alauddin Khilji, Qutub Minar complex

-

Upper design in Qutb Minar Complex

-

The Qutb Minar and surrounding ruins.

-

The tomb of the Emperor Shah 'Alam at the dargah of Qutb-Sahib at Mahrauli; a watercolor by Seeta Ram

-

Qutb Mosque Arch Ruin

-

Another view of the Qutub Minar Grounds

-

The Qutb Minar, looking up from its foot

-

The entrance to the Qutb Minar. Upper half taken to show closeup of the designs on top of the gate.

-

High resolution details of the calligraphy on one side of the Qutb Minar

-

Looking towards the Minar from under the adjoining ruins of an arch.

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Patel, A (2004). "Toward Alternative Receptions of Ghurid Architecture in North India (Late Twelfth-Early Thirtheenth Century CE)". Archives of Asian Art 54: 59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Javeed, Tabassum (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. Algora Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 0875864821. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Qutub MinarQutub Minar Govt. of India website.

- 1 2 Ali Javid, ʻAlī Jāvīd, Tabassum Javed. "World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India". Page.14,263. Google Books. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- 1 2 Epigraphia Indo Moslemica, 1911–12, p. 13.

- ↑ Chandra, Satish (2003). History of architecture and ancient building materials in India. Tech Books International. p. 107. ISBN 8188305030..

- ↑ Page, J. A. (1926) "An Historical Memoir on the Qutb, Delhi" Memoirs of the Archaeological Society of India 22: OCLC 5433409; republished (1970) Lakshmi Book Store, New Delhi, OCLC 202340

- ↑ "Discover new treasures around Qutab". The Hindu. 28 March 2006. Retrieved 14 August 2009..

- ↑ "Another wonder revealed: Qutub Minar draws most tourists, Taj a distant second". Indian Express. 25 July 2007. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ↑ QutubMinarDelhi.com. "Alai Darwaza" . Retrieved on 5 August 2015.

- ↑ World Heritage Sites – Humayun's Tomb: Characteristics of Indo-Islamic architecture Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

- ↑ QutubMinarDelhi.com. "Qutub Minar" . Retrieved on 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Nath, R. (1978). History of Sultanate architecture. Abhinav Publications. p. 22.

- ↑ Schimmel, Annemarie (1982). Islam in India and Pakistan. BRILL. p. 4. ISBN 90-04-06479-6.

- ↑ Batra, N. L. (1996). Heritage conservation: preservation and restoration of monuments. Aryan Books International. p. 176. ISBN 81-7305-108-9.

- 1 2 Delhi city guide, by Eicher Goodearth Limited, Delhi Tourism. Published by Eicher Goodearth Limited, 1998. ISBN 81-900601-2-0. Page 181-182.

- ↑ Plaque at Qutub Minar

- ↑ Schimmel, Annemarie; Burzine K. Waghmar (2004). The empire of the great Mughals. Reaktion Books. p. 267. ISBN 1-86189-185-7.

- 1 2 "When Delhi shook, Qutub stood still". Indian Express. 15 October 2005. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ↑ "EU maps faultlines to save Qutab". Indian Express. 14 December 2004. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ↑ "No decision on re-opening Qutub Minar for public: Government". The Times of India. 23 August 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ↑ Southern Central Asia, A.H. Dani, History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol.4, Part 2, Ed. Clifford Edmund Bosworth, M.S.Asimov, (Motilal Banarsidass, 2000), 564.

- 1 2 Sharif, Mian Mohammad (1963). A History of Muslim Philosophy: With Short Accounts of Other Disciplines and the Modern Renaissance in Muslim Lands. Harrassowitz. p. 1098.

- ↑ William Pickthall, Marmaduke; Muhammad Asad (1975). Islamic culture, Volume 49. Islamic Culture Board. p. 50.

- ↑ Adhai-din-ka Jhonpra Mosque archnet.org.

- ↑ Maulana Hakim Saiyid Abdul Hai "Hindustan Islami Ahad Mein" (Hindustan under Islamic rule), Eng Trans by Maulana Abdul Hasan Nadwi

- ↑ Index_1200-1299: Qutb ud-Din Aibak and the Qubbat ul-Islam mosqueColumbia University

- ↑ Vikramjit Singh Rooprai. "Untold story of the Qutub Minar". Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ↑ QutubMinarDelhi.com. "Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque" . Retrieved on 5 August 2015.

- ↑ QutubMinarDelhi.com. "Iron Pillar of Delhi" . Retrieved on 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "Iron pillar at Qutub Minar weighs 6,511 kg: study". The Hindu. 5 February 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ↑ QutubMinarDelhi.com. "Tomb of Iltutmish" . Retrieved on 5 August 2015.

- ↑ QutubMinarDelhi.com. "Ala-ud-din's Madrasa and Tomb" . Retrieved on 5 August 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ Bhalla, A.S. Royal Tombs of India: 13th to 18th Century

- ↑ QutubMinarDelhi.com. "Alai Minar" . Retrieved on 5 August 2015.

- ↑ File:Plaque for Alai Minar, Qutub Minar complex.jpg

Notations

- Cole, Henry Hardy (1872). The Architecture of ancient Delhi : especially the buildings around the Kutb Minar. London : Published by the Arundel Society for Promoting the Knowledge of Art.

- Beglar, J. D.; Carlleyle, A. C . L. (1874). Archaeological Survey of India: Report for the Year 1871–72: Delhi, and Agra (1874). Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing.

- R. N. Munshi (1911). The History of the Kutb Minar (Delhi). G.R.Sindhe, Bombay.

Further reading

- Hearn, Gordon Risley (1906). The Seven Cities of Delhi. W. Thacker & Co., London.

- Munshi, Rustamji Nasarvanji (1911). The History of the Kutb Minar (Delhi). Bombay : G.R. Sindhe.

- Page, J. A, Archaeological Survey of India (1927). Guide to the Qutb, Delhi. Calcutta, Government of India, Central Publication Branch.

- The World heritage complex of the Qutub, by R. Balasubramaniam. Aryan Books International, 2005. ISBN 81-7305-293-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qutb Minar and its monuments, Delhi. |

- Entry in the UNESCO World Heritage Site List

- Qutub Minar

- Quwwat Al-Islam Mosque

- Corrosion resistance of Delhi iron pillar

- Nondestructive evaluation of the Delhi iron pillar Current Science, Indian Academy of Sciences, Vol. 88, No. 12, 25 June 2005 (PDF)

- Photo gallery of the Qutb complex

| ||||||||||||||||||||