Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi

| Iranian scholar Qutb al-Din Shirazi | |

|---|---|

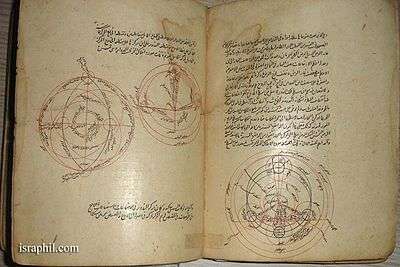

Photo taken from medieval manuscript by Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi. The image depicts an epicyclic planetary model. | |

| Born |

1236 AD Kazerun |

| Died |

February 7, 1311 AD Tabriz |

| Religion | Islam |

| Jurisprudence | Sufi |

| Main interest(s) | Mathematics, Astronomy, medicine, science and philosophy |

| Notable work(s) | Almagest, The Royal Present ,Pearly Crown, etc |

|

Influenced by

| |

|

Influenced

| |

Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (1236 – 1311) (Persian: قطبالدین محمود بن مسعود شیرازی) was a 13th-century Persian polymath[1] and poet who made contributions to astronomy, mathematics, medicine, physics, music theory, philosophy and Sufism.

Biography

He was born in Kazerun in October 1236 to a family with a tradition of Sufism. His father, Zia' al-Din Mas'ud Kazeruni was a physician by profession and also a leading Sufi of the Kazeruni order. Zia' Al-Din received his Kherqa (Sufi robe) from Shahab al-Din Omar Suhrawardi. Qutb al-Din was garbed by the Kherqa (Sufi robe) as blessing by his father at age of ten. Later on, he also received his own robe from the hands of Najib al-Din Bozgush Shirazni, a famous Sufi of the time. Quṭb al-Din began studying medicine under his father. His father practiced and taught medicine at the Mozaffari hospital in Shiraz. After the passing away of his father (when Qutb al-Din was 14), his uncle and other masters of the period trained him in medicine. He also studied the Qanun (the Canon) of the famous Persian scholar Avicenna and its commentaries. In particular he read the commentary of Fakhr al-Din Razi on the Canon of Medicine and Qutb al-Din raised many issues of his own. This led to his own decision to write his own commentary, where he resolved many of the issues in the company of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.

Qutb al-Din lost his father at the age of fourteen and replaced him as the ophthalmologist at the Mozaffari hospital in Shiraz. At the same time, he pursued his education under his uncle Kamal al-Din Abu'l Khayr and then Sharaf al-Din Zaki Bushkani, and Shams al-Din Mohammad Kishi. All three were expert teachers of the Canon of Avicenna. He quit his medical profession ten years later and began to devote his time to further education under the guidance of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi. When Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, the renowned scholar-vizier of the Mongol Holagu Khan established the observatory of Maragha, Qutb al-Din Shirazi became attracted to the city. He left Shiraz sometime after 1260 and was in Maragha about 1262. In Maragha, Qutb al-din resumed his education under Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, with whom he studied the al-Esharat wa'l-Tanbihat of Avicenna. He discussed the difficulties he had with Nasir al-Din al-Tusi on understanding the first book of the Canon of Avicenna. While working in the new observatory, studied astronomy under him. One of the important scientific projects was the completion of the new astronomical table (zij). In his testament (Wasiya), Nasir al-Din al-Tusi advises his son ṣil-a-Din to work with Qutb al-Din in the completion of the Zij.

Qutb-al-Din's stay in Maragha was short. Subsequently, he traveled to Khorasan in the company of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi where he stayed to study under Najm al-Din Katebi Qazvini in the town of Jovayn and become his assistant. Some time after 1268, he journeyed to Qazvin, Isfahan, Baghdad and later Konya in Anatolia. This was a time when the Persian poet Jalal al-Din Muhammad Balkhi (Rumi) was gaining fame there and it is reported that Qutb al-Din also met him. In Konya, he studied the Jam'e al-Osul of Ibn Al-Athir with Sadr al-Din Qunawi. The governor of Konya, Mo'in al-Din Parvana appointed him as the judge of Sivas and Malatya. It was during this time that he compiled the books the Meftāḥ al-meftāh, Ekhtiārāt al-moẓaffariya, and his commentary on Sakkāki. In the year 1282, he was envoy on behalf of the Ilkhanid Ahmad Takudar to Sayf al-Din Qalawun, the Mamluk ruler of Egypt. In his letter to Qalawun, the Ilkhanid ruler mentions Qutb al-Din as the chief judge. Qutb al-Din during this time collected various critiques and commentaries on Avicenna's Canon and used them on his commentary on the Kolliyāt. The last part of Qutb al-Din's active career was teaching the Canon of Avicenna and the Shefa of Avicenna in Syria. He soon left for Tabriz after that and died shortly after. He was buried in the Čarandāb cemetery of the city.

Shirazi identified observations by the scholar Avicenna in the 11th century and Ibn Bajjah in the 12th century as transits of Venus and Mercury.[2] However, Ibn Bajjah cannot have observed a transit of Venus, as none occurred in his lifetime.[3]

Qutb al-Din had an insatiable desire[1] for learning, which is evidenced by the twenty-four years he spent studying with masters of the time in order to write his commentary on the Kolliyāt. He was also distinguished by his extensive breadth of knowledge, a clever sense of humor and indiscriminate generosity.[1] He was also a master chess player and played the musical instrument known as the Rabab, a favorite instrument of the Persian poet Rumi.

Works

Mathematical

- Tarjoma-ye Taḥrir-e Oqlides a work on geometry in Persian in fifteen chapters containing mainly the translation of the work Nasir al-Din Tusi, completed in November 1282 and dedicated to Moʿin-al-Din Solaymān Parvāna.

- Risala fi Harkat al-Daraja" a work on Mathematics

Astronomy and Geography

- Eḵtiārāt-e moẓaffari It is a treatise on astronomy in Persian in four chapters and extracted from his other work Nehāyat al-edrāk. The work was dedicated to Mozaffar-al-Din Bulaq Arsalan.

- Fi ḥarakāt al-dahraja wa’l-nesba bayn al-mostawi wa’l-monḥani a written as an appendix to Nehāyat al-edrāk

- Nehāyat al-edrāk - The Limit of Accomplishment concerning Knowledge of the Heavens (Nehāyat al-edrāk fi dirayat al-aflak) completed in 1281, and The Royal Present (Al-Tuhfat al-Shahiya) completed in 1284. Both presented his models for planetary motion, improving on Ptolemy's principles.[4] In his The Limit of Accomplishment concerning Knowledge of the Heavens, he also discussed the possibility of heliocentrism.[5]

- Ketāb faʿalta wa lā talom fi’l-hayʾa, an Arabic work on astronomy, written for Aṣil-al-Din, son of Nasir al-Din Tusi

- Šarḥ Taḏkera naṣiriya on astronomy.

- Al-Tuḥfa al-šāhiya fi’l-hayʾa, an Arabic book on astronomy, having four chapters, written for Moḥammad b. Ṣadr-al-Saʿid, known as Tāj-al-Eslām Amiršāh

- *Ḥall moškelāt al-Majesṭi a book on astronomy, titled Ḥall moškelāt al-Majesṭi

Philosophical

- Dorrat al-tāj fi ḡorrat al-dabbāj Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi's most famous work is the Pearly Crown (Durrat al-taj li-ghurratt al-Dubaj), written in Persian around AD 1306 (705 AH). It is an Encyclopedic work on philosophy written for Rostam Dabbaj, the ruler of the Iranian land of Gilan. It includes philosophical outlook on natural sciences, theology, logic, public affairs, ethnics, mystiicsm, astronomy, mathematics, arithmetics and music.

- Šarḥ Ḥekmat al-ešrāq Šayḵ Šehāb-al-Din Sohravardi, on philosophy and mysticism of Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi and his philosophy of illumination in Arabic.

Medicine

- Al-Tuḥfat al-saʿdiyah also called Nuzhat al-ḥukamāʾ wa rawżat al-aṭibbāʾ, on medicine, a comprehensive commentary in five volumes on the Kolliyāt of the Canon of Avicenna written in Arabic.

- Risāla fi’l-baraṣ, a medical treatise on leprosy in Arabic

- Risāla fi bayān al-ḥājat ila’l-ṭibb wa ādāb al-aṭibbāʾ wa waṣāyā-hum

Religion, Sufism, Theology, Law, Linguistics and Rhetoric and others

- Al-Enteṣāf a gloss in Arabic on Zamakhshari's Qurʾan commentary, al-Kaššāf.

- Fatḥ al-mannān fi tafsir al-Qorʾān a comprehensive commentary on the Qurʾan in forty volumes, written in Arabic and also known by the title Tafsir ʿallāmi

- Ḥāšia bar Ḥekmat al-ʿayn on theology; it is a commentary of Ḥekmat al-ʿayn of Najm-al-Din ʿAli Dabirān Kātebi

- Moškelāt al-eʿrāb on Arabic syntax

- Moškelāt al-tafāsir or Moškelāt al-Qorʾān, on rhetoric

- Meftāḥ al-meftāhá, a commentary on the third section of the Meftāḥ al-ʿolum, a book on Arabic grammar and rhetoric by Abu Yaʿqub Seraj-al-Din Yusof Skkaki Khwarizmi

- Šarḥ Moḵtaṣar al-oṣul Ebn Ḥājeb, a commentary on Ebn Ḥājeb’s Montaha’l-soʾāl wa’l-ʿamal fi ʿelmay al-oṣul wa’l-jadwal, a book on the sources of law according to the Malikite school of thought

- Sazāvār-e Efteḵā, Moḥammad-ʿAli Modarres attributes a book by this title to Quṭb-al-Din, without providing any information about its content

- Tāj al-ʿolum A book attributed to him by Zerekli

- al-Tabṣera A book attributed to him by Zerekli

- A book on ethnics and poetry, Quṭb-al-Din is also credited with the authorship of a book on ethics in Persian, written for Malek ʿEzz-al-Din, the ruler of Shiraz. He also wrote poetry but apparently did not leave a divan (a book of poems)

Qutb al-Din was also a Sufi from a family of Sufis in Shiraz. He is famous for the commentary on Hikmat al-ishraq of Suhrawardi, the most influential work of Islamic Illuminist philosophy.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Sayyed ʿAbd-Allāh Anwār , Encyclopedia Iranica, "QOṬB-AL-DIN ŠIRĀZI, Maḥmud b. Żiāʾ-al-Din Masʿud b. Moṣleḥ",

- ↑ S. M. Razaullah Ansari (2002), History of oriental astronomy: proceedings of the joint discussion-17 at the 23rd General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union, organised by the Commission 41 (History of Astronomy), held in Kyoto, August 25–26, 1997, Springer, p. 137, ISBN 1-4020-0657-8

- ↑ Fred Espenak, Six Millennium Catalog of Venus Transits

- ↑ Kennedy, E. S. - Late Medieval Planetary Theory, Isis, Vol. 57, No. 3. (Autumn, 1966), pp. 365-378., The University of Chicago Press

- ↑ A. Baker and L. Chapter (2002), "Part 4: The Sciences". In M. M. Sharif, "A History of Muslim Philosophy", Philosophia Islamica.

External links

- Ragep, F. Jamil (2007). "Shīrāzī: Quṭb al‐Dīn Maḥmūd ibn Masʿūd Muṣliḥ al‐Shīrāzī". In Thomas Hockey; et al. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 1054–5. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2008) [1970-80]. "Quṭb Al-Dīn Al-Shīrāzī". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Sufism and Tariqat |

|---|

|

|

|

List of sufis |

|

|

|