Angioedema

| Angioedema | |

|---|---|

|

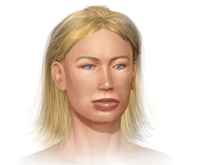

Allergic angioedema: this child is unable to open his eyes due to the swelling. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Allergy and immunology |

| ICD-10 | D84.1 , T78.3 |

| ICD-9-CM | 277.6, 995.1 |

| OMIM | 606860 106100 610618 |

| DiseasesDB | 13606 |

| MedlinePlus | 000846 |

| eMedicine | emerg/32 med/135 ped/101 |

| Patient UK | Angioedema |

| MeSH | D000799 |

Angioedema, also known as angiooedema, Quincke's edema, and angioneurotic edema, is the rapid swelling (edema) of the dermis, subcutaneous tissue,[1] mucosa and submucosal tissues. It is very similar to urticaria, but urticaria, commonly known as hives, occurs in the upper dermis.[1]

Cases where angioedema progresses rapidly should be treated as a medical emergency, as airway obstruction and suffocation can occur. Epinephrine may be life-saving when the cause of angioedema is allergic. In the case of hereditary angioedema, treatment with epinephrine has not been shown to be helpful.

Classification

Angioedema is classified as either hereditary or acquired.

Acquired angioedema (AAE) can be immunologic, nonimmunologic, or idiopathic.[2] It is usually caused by allergy and occurs together with other allergic symptoms and urticaria. It can also occur as a side effect to certain medications, particularly ACE inhibitors. It is characterized by repetitive episodes of swelling, frequently of the face, lips, tongue, limbs, and genitals. Edema of the gastrointestinal mucosa typically leads to severe abdominal pain; in the upper respiratory tract, it can be life-threatening.[3]

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) exists in three forms, all of which are caused by a genetic mutation inherited in an autosomal dominant form. They are distinguished by the underlying genetic abnormality. Types I and II are caused by mutations in the SERPING1 gene, which result in either diminished levels of the C1-inhibitor protein (type I HAE) or dysfunctional forms of the same protein (type II HAE). Type III HAE has been linked with mutations in the F12 gene, which encodes the coagulation protein factor XII. All forms of HAE lead to abnormal activation of the complement system, and all forms can cause swelling elsewhere in the body, such as the digestive tract. If HAE involves the larynx, it can cause life-threatening asphyxiation.[4] The pathogenesis of this disorder is suspected to be related to unopposed activation of the contact pathway by the initial generation of kallikrein and/or clotting factor XII by damaged endothelial cells. The end product of this cascade, bradykinin, is produced in large amounts and is believed to be the predominant mediator leading to increased vascular permeability and vasodilation that induces typical angioedema "attacks".[5]

Signs and symptoms

The skin of the face, normally around the mouth, and the mucosa of the mouth and/or throat, as well as the tongue, swell over the period of minutes to hours. The swelling can also occur elsewhere, typically in the hands. The swelling can be itchy or painful. There may also be slightly decreased sensation in the affected areas due to compression of the nerves. Urticaria (hives) may develop simultaneously.

In severe cases, stridor of the airway occurs, with gasping or wheezy inspiratory breath sounds and decreasing oxygen levels. Tracheal intubation is required in these situations to prevent respiratory arrest and risk of death.

Sometimes, the cause is recent exposure to an allergen (e.g. peanuts), but more often it is either idiopathic (unknown) or only weakly correlated to allergen exposure.

In hereditary angioedema, often no direct cause is identifiable, although mild trauma, including dental work and other stimuli, can cause attacks.[6] There is usually no associated itch or urticaria, as it is not an allergic response. Patients with HAE can also have recurrent episodes (often called "attacks") of abdominal pain, usually accompanied by intense vomiting, weakness, and in some cases, watery diarrhea, and an unraised, nonitchy splotchy/swirly rash. These stomach attacks can last one to five days on average, and can require hospitalization for aggressive pain management and hydration. Abdominal attacks have also been known to cause a significant increase in the patient's white blood cell count, usually in the vicinity of 13,000 to 30,000. As the symptoms begin to diminish, the white count slowly begins to decrease, returning to normal when the attack subsides. As the symptoms and diagnostic tests are almost indistinguishable from an acute abdomen (e.g. perforated appendicitis) it is possible for undiagnosed HAE patients to undergo laparotomy (operations on the abdomen) or laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) that turns out to have been unnecessary.

HAE may also cause swelling in a variety of other locations, most commonly the limbs, genitals, neck, throat and face. The pain associated with these swellings varies from mildly uncomfortable to agonizing pain, depending on its location and severity. Predicting where and when the next episode of edema will occur is impossible. Most patients have an average of one episode per month, but there are also patients who have weekly episodes or only one or two episodes per year. The triggers can vary and include infections, minor injuries, mechanical irritation, operations or stress. In most cases, edema develops over a period of 12–36 hours and then subsides within 2–5 days.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made on the clinical picture. Routine blood tests (complete blood count, electrolytes, renal function, liver enzymes) are typically performed. Mast cell tryptase levels may be elevated if the attack was due to an acute allergic (anaphylactic) reaction. When the patient has been stabilized, particular investigations may clarify the exact cause; complement levels, especially depletion of complement factors 2 and 4, may indicate deficiency of C1-inhibitor. HAE type III is a diagnosis of exclusion consisting of observed angioedema along with normal C1 levels and function.

The hereditary form (HAE) often goes undetected for a long time, as its symptoms resemble those of more common disorders, such as allergy or intestinal colic. An important clue is the failure of hereditary angioedema to respond to antihistamines or steroids, a characteristic that distinguishes it from allergic reactions. It is particularly difficult to diagnose HAE in patients whose episodes are confined to the gastrointestinal tract. Besides a family history of the disease, only a laboratory analysis can provide final confirmation. In this analysis, it is usually a reduced complement factor C4, rather than the C1-INH deficiency itself, that is detected. The former is used during the reaction cascade in the complement system of immune defense, which is permanently overactive due to the lack of regulation by C1-INH.

Pathophysiology

Bradykinin plays a critical role in all forms of hereditary angioedema.[7] This peptide is a potent vasodilator and increases vascular permeability, leading to rapid accumulation of fluid in the interstitium. This is most obvious in the face, where the skin has relatively little supporting connective tissue, and edema develops easily. Bradykinin is released by various cell types in response to numerous different stimuli; it is also a pain mediator. Dampening or inhibiting bradykinin has been shown to relieve HAE symptoms.

Various mechanisms that interfere with bradykinin production or degradation can lead to angioedema. ACE inhibitors block ACE, the enzyme that among other actions, degrades bradykinin. In hereditary angioedema, bradykinin formation is caused by continuous activation of the complement system due to a deficiency in one of its prime inhibitors, C1-esterase (aka: C1-inhibitor or C1INH), and continuous production of kallikrein, another process inhibited by C1INH. This serine protease inhibitor (serpin) normally inhibits the association of C1r and C1s with C1q to prevent the formation of the C1-complex, which - in turn - activates other proteins of the complement system. Additionally, it inhibits various proteins of the coagulation cascade, although effects of its deficiency on the development of hemorrhage and thrombosis appear to be limited.

The three types of hereditary angioedema are:

- Type I - decreased levels of C1INH (85%);

- Type II - normal levels, but decreased function of C1INH (15%);

- Type III - no detectable abnormality in C1INH, occurs in an X-linked dominant fashion and therefore mainly affects women; it can be exacerbated by pregnancy and use of hormonal contraception (exact frequency uncertain).[8] It has been linked with mutations in the factor XII gene.[9]

Angioedema can be due to antibody formation against C1INH; this is an autoimmune disorder. This acquired angioedema is associated with the development of lymphoma.

Consumption of foods which are themselves vasodilators, such as alcoholic beverages or cinnamon, can increase the probability of an angioedema episode in susceptible patients. If the episode occurs at all after the consumption of these foods, its onset may be delayed overnight or by some hours, making the correlation with their consumption somewhat difficult. In contrast, consumption of bromelain in combination with turmeric may be beneficial in reducing symptoms.[10]

The use of ibuprofen or aspirin may increase the probability of an episode in some patients. The use of acetaminophen typically has a smaller, but still present, increase in the probability of an episode.

Management

Allergic

In allergic angioedema, avoidance of the allergen and use of antihistamines may prevent future attacks. Cetirizine is a commonly prescribed antihistamine for angioedema. Some patients have reported success with the combination of a nightly low dose of cetirizine to moderate the frequency and severity of attacks, followed by a much higher dose when an attack does appear. Severe angioedema cases may require desensitization to the putative allergen, as mortality can occur. Chronic cases require steroid therapy, which generally leads to a good response. In cases where allergic attack is progressing towards airway obstruction, epinephrine may be life-saving.

Drug induction

ACE inhibitors can induce angioedema.[11][12][13] ACE inhibitors block the enzyme ACE so it can no longer degrade bradykinin; thus, bradykinin accumulates and causes angioedema.[11][12] This complication appears more common in African-Americans.[14] In people with ACE inhibitor angioedema, the drug needs to be discontinued and an alternative treatment needs to be found, such as an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB)[15] which has a similar mechanism but does not affect bradykinin. However, this is controversial, as small studies have shown some patients with ACE inhibitor angioedema can develop it with ARBs, as well.[16][17]

Hereditary

In hereditary angioedema, specific stimuli that have previously led to attacks may need to be avoided in the future. It does not respond to antihistamines, corticosteroids, or epinephrine. Acute treatment consists of C1-INH concentrate from donor blood, which must be administered intravenously. In an emergency, fresh frozen blood plasma, which also contains C1-INH, can also be used. However, in most European countries, C1-INH concentrate is only available to patients who are participating in special programmes.

Future attacks of hereditary angioedema can be prevented by the use of androgens such as danazol, oxandrolone or methyltestosterone. These agents increase the level of aminopeptidase P, an enzyme that inactivates kinins;[18] kinins (especially bradykinin) are responsible for the manifestations of angioedema.

Acquired

In acquired angioedema, HAE types I and II, and nonhistaminergic angioedema, antifibrinolytics such as tranexamic acid or ε-aminocaproic acid may be effective. Cinnarizine may also be useful because it blocks the activation of C4 and can be used in patients with liver disease, while androgens cannot.[19]

History

Heinrich Quincke first described the clinical picture of angioedema in 1882,[20] though there had been some earlier descriptions of the condition.[21][22][23]

William Osler remarked in 1888 that some cases may have a hereditary basis; he coined the term "hereditary angio-neurotic edema".[24]

The link with C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency was proved in 1963.[25]

Epidemiology

There are as many as 80,000 to 112,000 emergency department (ED) visits for angioedema annually, and it ranks as the top allergic disorder resulting in hospitalization in the U.S..[26]

See also

- Gleich's syndrome (unexplained angioedema with high eosinophil counts)

- Drug-induced angioedema

References

- 1 2 "angioedema" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Axelrod, S; Davis-Lorton, M (2011). "Urticaria and angioedema". The Mount Sinai journal of medicine, New York 78 (5): 784–802. doi:10.1002/msj.20288. PMID 21913206.

- ↑ Moon, MD, Amanda T; Heymann, MD, Warren R. "Acquired Angioedema". MedScape. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ Zuraw BL (September 2008). "Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema". N. Engl. J. Med. 359 (10): 1027–36. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0803977. PMID 18768946.

- ↑ Loew, Burr. "A 68-Year-Old Woman With Recurrent Abdominal Pain, Nausea, and Vomiting". MedScape. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Bork K, Barnstedt Se (August 2003). "Laryngeal edema and death from asphyxiation after tooth extraction in four patients with hereditary angioedema". J Am Dent Assoc 134 (8): 1088–94. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0323. PMID 12956349.

- ↑ Bas M, Adams V, Suvorava T, Niehues T, Hoffmann TK, Kojda G (2007). "Nonallergic angioedema: role of bradykinin". Allergy 62 (8): 842–56. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01427.x. PMID 17620062.

- ↑ Bork K, Barnstedt SE, Koch P, Traupe H (2000). "Hereditary angioedema with normal C1-inhibitor activity in women". Lancet 356 (9225): 213–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02483-1. PMID 10963200.

- ↑ Cichon S, Martin L, Hennies HC; et al. (2006). "Increased activity of coagulation factor XII (Hageman factor) causes hereditary angioedema type III". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79 (6): 1098–104. doi:10.1086/509899. PMC 1698720. PMID 17186468.

- ↑ University of Maryland Medical Center. Angioedema. http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/angioedema-000011.htm

- 1 2 Sabroe RA; Black AK (February 1997). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angio-oedema". British Journal of Dermatology 136 (2): 153–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb14887.x. PMID 9068723.

- 1 2 Israili ZH; Hall WD (August 1, 1992). "Cough and angioneurotic edema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. A review of the literature and pathophysiology". Annals of Internal Medicine 117 (3): 234–42. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-117-3-234. PMID 1616218.

- ↑ Kostis JB; Kim HJ; Rusnak J; Casale T; Kaplan A; Corren J; Levy E (July 25, 2005). "Incidence and characteristics of angioedema associated with enalapril". Archives of Internal Medicine 165 (14): 1637–42. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.14.1637. PMID 16043683.

- ↑ Brown NJ; Ray WA; Snowden M; Griffin MR (July 1996). "Black Americans have an increased rate of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema". Clinical Pharmacologic Therapy 60 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90161-7. PMID 8689816.

- ↑ Dykewicz, MS (August 2004). "Cough and angioedema from angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: new insights into mechanisms and management". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology 4 (4): 267–70. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136759.43571.7f. PMID 15238791.

- ↑ Malde B; Regalado J; Greenberger PA (January 2007). "Investigation of angioedema associated with the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 98 (1): 57–63. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60860-5. PMID 17225721.

- ↑ Cicardi M; Zingale LC; Bergamaschini L; Agostoni A (April 26, 2004). "Angioedema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use: outcome after switching to a different treatment". Archives of Internal Medicine 164 (8): 910–3. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.8.910. PMID 15111379.

- ↑ Drouet C, Désormeaux A, Robillard J, Ponard D, Bouillet L, Martin L; et al. (2008). "Metallopeptidase activities in hereditary angioedema: effect of androgen prophylaxis on plasma aminopeptidase P". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 121 (2): 429–33. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.048. PMID 18158172.

- ↑ http://www.iaari.hbi.ir/journal/archive/articles/v4n3mor.pdf

- ↑ Quincke H (1882). "Über akutes umschriebenes Hautödem". Monatsh Prakt Derm 1: 129–131.

- ↑ synd/482 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Marcello Donati. De medica historia mirabili. Mantuae, per Fr. Osanam, 1586

- ↑ J. L. Milton. On giant urticaria. Edinburgh Medical Journal, 1876, 22: 513-526.

- ↑ Osler W (1888). "Hereditary angio-neurotic oedema". Am J Med Sci 95 (2): 362–67. doi:10.1097/00000441-188804000-00004. PMID 20145434.

- ↑ Donaldson VH, Evans RR (July 1963). "A biochemical abnormality in hereditary angioneurotic edema: absence of serum inhibitor of C' 1-esterase". Am. J. Med. 35: 37–44. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(63)90162-1. PMID 14046003.

- ↑ http://healthnews.uc.edu/news/?/24791/

External links

- Angioedema at DMOZ

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||