Quasi-geostrophic equations

While geostrophic motion refers to the wind that would result from an exact balance between the Coriolis force and horizontal pressure gradient forces,[1] Quasi-geostrophic (QG) motion refers to flows where the Coriolis force and pressure gradient forces are almost in balance, but with inertia also having an effect. [2]

Origin

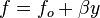

Atmospheric and oceanographic flows take place over horizontal length scales which are very large compared to their vertical length scale, and so they can be described using the shallow water equations. The Rossby number is a dimensionless number which characterises the strength of inertia compared to the strength of the Coriolis force. The quasi-geostrophic equations are approximations to the shallow water equations in the limit of small Rossby number, so that inertial forces are an order of magnitude smaller than the Coriolis and pressure forces. If the Rossby number is equal to zero then we recover geostrophic flow.

Derivation of the single-layer QG equations

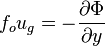

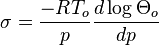

In Cartesian coordinates, the components of the geostrophic wind are

-

(1a)

(1a) -

(1b)

(1b)

where  is the geopotential height.

is the geopotential height.

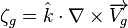

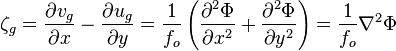

The geostrophic vorticity

can therefore be expressed in terms of the geopotential as

-

(2)

(2)

Equation (2) can be used to find  from a known field

from a known field  . Alternatively, it can also be used to determine

. Alternatively, it can also be used to determine  from a known distribution of

from a known distribution of  by inverting the Laplacian operator.

by inverting the Laplacian operator.

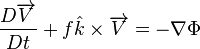

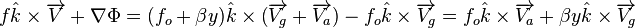

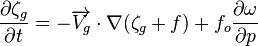

The quasi-geostrophic vorticity equation can be obtained from the  and

and  components of the quasi-geostrophic momentum equation which can then be derived from the horizontal momentum equation

components of the quasi-geostrophic momentum equation which can then be derived from the horizontal momentum equation

-

(3)

(3)

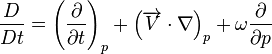

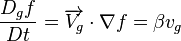

The material derivative in (3) is defined by

-

(4)

(4) - where

is the pressure change following the motion.

is the pressure change following the motion.

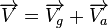

The horizontal velocity  can be separated into a geostrophic

can be separated into a geostrophic  and an ageostrophic

and an ageostrophic  part

part

-

(5)

(5)

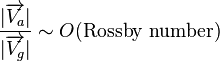

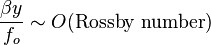

Two important assumptions of the quasi-geostrophic approximation are

- 1.

, or, more precisely

, or, more precisely  .

. - 2. the beta-plane approximation

with

with

- 1.

The second assumption justifies letting the Coriolis parameter have a constant value  in the geostrophic approximation and approximating its variation in the Coriolis force term by

in the geostrophic approximation and approximating its variation in the Coriolis force term by  .[3] However, because the acceleration following the motion, which is given in (1) as the difference between the Coriolis force and the pressure gradient force, depends on the departure of the actual wind from the geostrophic wind, it is not permissible to simply replace the velocity by its geostrophic velocity in the Coriolis term.[3] The acceleration in (3) can then be rewritten as

.[3] However, because the acceleration following the motion, which is given in (1) as the difference between the Coriolis force and the pressure gradient force, depends on the departure of the actual wind from the geostrophic wind, it is not permissible to simply replace the velocity by its geostrophic velocity in the Coriolis term.[3] The acceleration in (3) can then be rewritten as

-

(6)

(6)

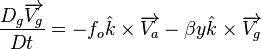

The approximate horizontal momentum equation thus has the form

-

(7)

(7)

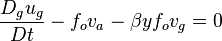

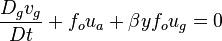

Expressing equation (7) in terms of its components,

-

(8a)

(8a)

-

(8b)

(8b)

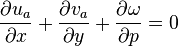

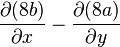

Taking  , and noting that geostrophic wind is nondivergent (ie,

, and noting that geostrophic wind is nondivergent (ie,  ), the vorticity equation is

), the vorticity equation is

-

(9)

(9)

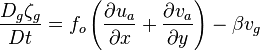

Because  depends only on

depends only on  (ie,

(ie,  ) and that the divergence of the ageostrophic wind can be written in terms of

) and that the divergence of the ageostrophic wind can be written in terms of  based on the continuity equation

based on the continuity equation

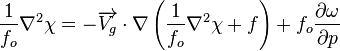

equation (9) can therefore be written as

-

(10)

(10)

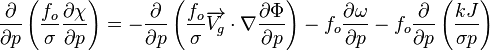

Defining the geopotential tendency  and noting that partial differentiation may be reversed, equation (10) can be rewritten in terms of

and noting that partial differentiation may be reversed, equation (10) can be rewritten in terms of  as

as

-

(11)

(11)

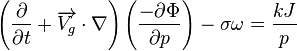

The right-hand side of equation (11) depends on variables  and

and  . An analogous equation dependent on these two variables can be derived from the thermodynamic energy equation

. An analogous equation dependent on these two variables can be derived from the thermodynamic energy equation

-

(12)

(12)

where  and

and  is the potential temperature corresponding to the basic state temperature. In the midtroposphere,

is the potential temperature corresponding to the basic state temperature. In the midtroposphere,  ≈

≈  .

.

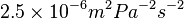

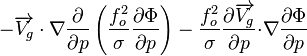

Multiplying (12) by  and differentiating with respect to

and differentiating with respect to  and using the definition of

and using the definition of  yields

yields

-

(13)

(13)

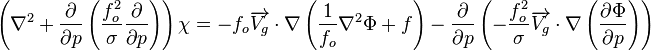

If for simplicity  were set to 0, eliminating

were set to 0, eliminating  in equations (11) and (13) yields [4]

in equations (11) and (13) yields [4]

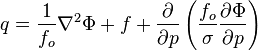

-

(14)

(14)

Equation (14) is often referred to as the geopotential tendency equation. It relates the local geopotential tendency (term A) to the vorticity advection distribution (term B) and thickness advection (term C).

Using the chain rule of differentiation, term C can be written as

-

(15)

(15)

But based on the thermal wind relation,

-

.

.

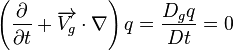

In other words, is perpendicular to

is perpendicular to  and the second term in equation (15) disappears. The first term can be combined with term B in equation (14) which, upon division by

and the second term in equation (15) disappears. The first term can be combined with term B in equation (14) which, upon division by  can be expressed in the form of a conservation equation [5]

can be expressed in the form of a conservation equation [5]

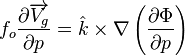

-

(16)

(16)

where  is the quasi-geostrophic potential vorticity defined by

is the quasi-geostrophic potential vorticity defined by

-

(17)

(17)

The three terms of equation (17) are, from left to right, the geostrophic relative vorticity, the planetary vorticity and the stretching vorticity.

Implications

As an air parcel moves about in the atmosphere, its relative, planetary and stretching vorticities may change but equation (17) shows that the sum of the three must be conserved following the geostrophic motion.

Equation (17) can be used to find  from a known field

from a known field  . Alternatively, it can also be used to predict the evolution of the geopotential field given an initial distribution of

. Alternatively, it can also be used to predict the evolution of the geopotential field given an initial distribution of  and suitable boundary conditions by using an inversion process.

and suitable boundary conditions by using an inversion process.

More importantly, the quasi-geostrophic system reduces the five-variable primitive equations to a one-equation system where all variables such as  ,

,  and

and  can be obtained from

can be obtained from  or height

or height  .

.

Also, because  and

and  are both defined in terms of

are both defined in terms of  , the vorticity equation can be used to diagnose vertical motion provided that the fields of both

, the vorticity equation can be used to diagnose vertical motion provided that the fields of both  and

and  are known.

are known.

References

- ↑ Phillips, N.A. (1963). “Geostrophic Motion.” Reviews of Geophysics Volume 1, No. 2., p. 123.

- ↑ Kundu, P.K. and Cohen, I.M. (2008). Fluid Mechanics, 4th edition. Elsevier., p. 658.

- 1 2 Holton, J.R. (2004). Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology, 4th Edition. Elsevier., p. 149.

- ↑ Holton, J.R. (2004). Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology, 4th Edition. Elsevier., p. 157.

- ↑ Holton, J.R. (2004). Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology, 4th Edition. Elsevier., p. 160.