Baryon number

| Flavour in particle physics |

|---|

| Flavour quantum numbers |

|

| Related quantum numbers |

|

| Combinations |

|

| Flavour mixing |

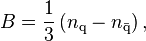

In particle physics, the baryon number is a strictly conserved additive quantum number of a system. It is defined as

where nq is the number of quarks, and nq is the number of antiquarks. Baryons (three quarks) have a baryon number of +1, mesons (one quark, one antiquark) have a baryon number of 0, and antibaryons (three antiquarks) have a baryon number of −1. Exotic hadrons like pentaquarks (four quarks, one antiquark) and tetraquarks (two quarks, two antiquarks) are also classified as baryons and mesons depending on their baryon number.

Baryon number vs. quark number

Quarks carry not only electric charge, but also charges such as color charge and weak isospin. Because of a phenomenon known as color confinement, a hadron cannot have a net color charge; that is, the total color charge of a particle has to be zero ("white"). A quark can have one of three "colors", dubbed "red", "green", and "blue".

For normal hadrons, a white color can thus be achieved in one of three ways:

- A quark of one color with an antiquark of the corresponding anticolor, giving a meson with baryon number 0,

- Three quarks of different colors, giving a baryon with baryon number +1,

- Three antiquarks into an antibaryon with baryon number −1.

The baryon number was defined long before the quark model was established, so rather than changing the definitions, particle physicists simply gave quarks one third the baryon number. Nowadays it might be more accurate to speak of the conservation of quark number.

In theory, exotic hadrons can be formed by adding pairs of quark and antiquark, provided that each pair has a matching color/anticolor. For example, a pentaquark (four quarks, one antiquark) could have the individual quark colors: red, green, blue, blue, and antiblue.

Particles not formed of quarks

Particles without any quarks have a baryon number of zero. Such particles include leptons (electron, muon, tau and their neutrinos) and gauge bosons (photon, W and Z bosons, gluons, and the Higgs boson); or the hypothetical graviton.

Conservation

The baryon number is conserved in nearly all the interactions of the Standard Model. 'Conserved' means that the sum of the baryon number of all incoming particles is the same as the sum of the baryon numbers of all particles resulting from the reaction. An exception is the chiral anomaly proposed by some extensions of the standard model. However, sphalerons are not all that common. Electroweak sphalerons can only change the baryon number by 3. No experimental evidence of sphalerons has yet been observed.

The still hypothetical idea of a grand unified theory allows for the changing of a baryon into several leptons (see B − L), thus violating the conservation of both baryon and lepton numbers.[1] Proton decay would be an example of such a process taking place, but has never been observed.

See also

References

- ↑ Griffiths, David (2008). Introduction to Elementary Particles (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 77. ISBN 9783527618477.

In the grand unified theories new interactions are contemplated, permitting decays such as p+ → e+ + π0 or p+ → ν

μ + π+ in which baryon number and lepton number change.