Quantum phase transition

In physics, a quantum phase transition (QPT) is a phase transition between different quantum phases (phases of matter at zero temperature). Contrary to classical phase transitions, quantum phase transitions can only be accessed by varying a physical parameter—such as magnetic field or pressure—at absolute zero temperature. The transition describes an abrupt change in the ground state of a many-body system due to its quantum fluctuations. Such a quantum phase transition can be a second-order phase transition.[1]

Classical description

To understand quantum phase transitions, it is useful to contrast them to classical phase transitions (CPT) (also called thermal phase transitions).[2] A CPT describes a cusp in the thermodynamic properties of a system. It signals a reorganization of the particles; A typical example is the freezing transition of water describing the transition between liquid and solid. The classical phase transitions are driven by a competition between the energy of a system and the entropy of its thermal fluctuations. A classical system does not have entropy at zero temperature and therefore no phase transition can occur. Their order is determined by the first discontinuous derivative of a thermodynamic potential.

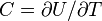

A phase transition from water to ice, for example, involves latent heat (a discontinuity of the heat capacity  ) and is of first order. A phase transition from a ferromagnet to a paramagnet is continuous and is of second order. (See phase transition for Ehrenfest's classification of phase transitions by the derivative of free energy which is discontinuous at the transition).

These continuous transitions from an ordered to a disordered phase are described by an order parameter, which is zero in the

disordered and non-zero in the ordered phase. For the aforementioned ferromagnetic transition, the order parameter would represent the total magnetization of the system.

) and is of first order. A phase transition from a ferromagnet to a paramagnet is continuous and is of second order. (See phase transition for Ehrenfest's classification of phase transitions by the derivative of free energy which is discontinuous at the transition).

These continuous transitions from an ordered to a disordered phase are described by an order parameter, which is zero in the

disordered and non-zero in the ordered phase. For the aforementioned ferromagnetic transition, the order parameter would represent the total magnetization of the system.

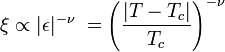

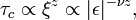

Although the thermodynamic average of the order parameter is zero in the disordered state, its fluctuations can be non-zero and become long-ranged in the vicinity of the critical point, where their typical length scale ξ (correlation length) and typical fluctuation decay time scale τc (correlation time) diverge:

where

is defined as the relative deviation from the critical temperature Tc. We call ν the (correlation length) critical exponent and z the dynamical critical exponent. Critical behavior of finite temperature phase transitions is fully described by classical thermodynamics; quantum mechanics does not play any role even if the actual phases require a quantum mechanical description (e.g. superconductivity).

Quantum description

Talking about quantum phase transitions means talking about transitions at T = 0: by tuning a non-temperature parameter like pressure, chemical composition or magnetic field, one could suppress e.g. some transition temperature like the Curie- or Néel- temperature to 0 K.

As such a QPT cannot be driven by thermal fluctuations, quantum fluctuations have to be the underlying source. The terminology used for the description of classical phase transitions is nevertheless applied. As for a classical second order transition, a quantum second order transition has a quantum critical point (QCP) where the quantum fluctuations driving the transition diverge and become scale invariant in space and time. Also at finite temperatures, quantum fluctuations with an energy scale of ħω and classical fluctuations with an energy scale of kBT compete. For ħω > kBT, quantum fluctuations will dominate the system's properties, ω is the characteristic frequency of a quantum oscillation and inversely proportional to the correlation time.

As a consequence it should be possible to detect remnants or traces of the transition also at low enough finite temperatures: a quantum critical region in proximity of the actual transition or the quantum critical point. These traces become manifest in unconventional and unexpected physical behavior like novel non Fermi liquid phases. From a theoretical point of view, a phase diagram like the one shown on the right is expected: the QPT separates an ordered from a disordered phase (often, the low temperature disordered phase is referred to as 'quantum' disordered).

At high enough temperatures, the system is disordered and purely classical. Around the classical phase transition, the system is governed by classical thermal fluctuations (light blue area). This region becomes narrower with decreasing energies and converges towards the quantum critical point (QCP). Experimentally, the 'quantum critical' phase, which is still governed by quantum fluctuations, is the most interesting one.

See also

References

- ↑ Jaeger, Gregg (1 May 1998). "The Ehrenfest Classification of Phase Transitions: Introduction and Evolution". Archive for History of Exact Sciences 53 (1): 51–81. doi:10.1007/s004070050021.

- ↑ Jaeger, Gregg (1 May 1998). "The Ehrenfest Classification of Phase Transitions: Introduction and Evolution". Archive for History of Exact Sciences 53 (1): 51–81. doi:10.1007/s004070050021.

- Sachdev, Subir (2011). Quantum Phase Transitions. Cambridge University Press. (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0-521-51468-2.

- Carr, Lincoln D. (2010). Understanding Quantum Phase Transitions. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-0251-9.

- Vojta, Thomas (2000). "Quantum phase transitions in electronic systems". Annalen der Physik. doi:10.1002/1521-3889(200006)9:6<403::AID-ANDP403>3.0.CO;2-R.

- Amusia, M., Popov, K., Shaginyan, V., Stephanovich, V. (2014). Theory of Heavy-Fermion Compounds - Theory of Strongly Correlated Fermi-Systems. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-10825-4.