Measurement in quantum mechanics

A measurement always causes the system to jump into an eigenstate of the dynamical variable that is being measured, the eigenvalue this eigenstate belongs to being equal to the result of the measurement.

The framework of quantum mechanics requires a careful definition of measurement. The issue of measurement lies at the heart of the problem of the interpretation of quantum mechanics, for which there is currently no consensus.

Measurement from a practical point of view

Measurement plays an important role in quantum mechanics, and it is viewed in different ways among various interpretations of quantum mechanics. In spite of considerable philosophical differences, different views of measurement almost universally agree on the practical question of what results form a routine quantum-physics laboratory measurement. To understand this, the Copenhagen interpretation, which has been commonly used,[1] is employed in this article.

Qualitative overview

In classical mechanics, a simple system consisting of only one single particle is fully described by the position  and momentum

and momentum  of the particle. As an analogue, in quantum mechanics a system is described by its quantum state, which contains the probabilities of possible positions and momenta. In mathematical language, all possible pure states of a system form an abstract vector space called Hilbert space, which is typically infinite-dimensional. A pure state is represented by a state vector in the Hilbert space.

of the particle. As an analogue, in quantum mechanics a system is described by its quantum state, which contains the probabilities of possible positions and momenta. In mathematical language, all possible pure states of a system form an abstract vector space called Hilbert space, which is typically infinite-dimensional. A pure state is represented by a state vector in the Hilbert space.

Once a quantum system has been prepared in laboratory, some measurable quantity such as position or energy is measured. For pedagogic reasons, the measurement is usually assumed to be ideally accurate. The state of a system after measurement is assumed to "collapse" into an eigenstate of the operator corresponding to the measurement. Repeating the same measurement without any evolution of the quantum state will lead to the same result. If the preparation is repeated, subsequent measurements will likely lead to different results.

The predicted values of the measurement are described by a probability distribution, or an "average" (or "expectation") of the measurement operator based on the quantum state of the prepared system.[2] The probability distribution is either continuous (such as position and momentum) or discrete (such as spin), depending on the quantity being measured.

The measurement process is often considered as random and indeterministic. Nonetheless, there is considerable dispute over this issue. In some interpretations of quantum mechanics, the result merely appears random and indeterministic, whereas in other interpretations the indeterminism is core and irreducible. A significant element in this disagreement is the issue of "collapse of the wavefunction" associated with the change in state following measurement. There are many philosophical issues and stances (and some mathematical variations) taken—and near universal agreement that we do not yet fully understand quantum reality. In any case, our descriptions of dynamics involve probabilities, not certainties.

Quantitative details

The mathematical relationship between the quantum state and the probability distribution is, again, widely accepted among physicists, and has been experimentally confirmed countless times. This section summarizes this relationship, which is stated in terms of the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics.

Measurable quantities ("observables") as operators

It is a postulate of quantum mechanics that all measurements have an associated operator (called an observable operator, or just an observable), with the following properties:

- The observable is a self-adjoint operator mapping a Hilbert space (namely, the state space, which consists of all possible quantum states) into itself.

- Thus, the observable's eigenvectors (called an eigenbasis) form an orthonormal basis that span the state space in which that observable exists. Any quantum state can be represented as a superposition of the eigenstates of an observable.

- Hermitian operators' eigenvalues are real. The possible outcomes of a measurement are precisely the eigenvalues of the given observable.

- For each eigenvalue there are one or more corresponding eigenvectors (eigenstates). A measurement results in the system being in the eigenstate corresponding to the eigenvalue result of the measurement. If the eigenvalue determined from the measurement corresponds to more than one eigenstate ("degeneracy"), instead of being in a definite state, the system is in a sub-space of the measurement operator corresponding to all the states having that eigenvalue.

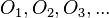

Important examples of observables are:

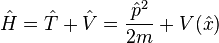

- The Hamiltonian operator

, which represents the total energy of the system. In nonrelativistic quantum mechanics the nonrelativistic Hamiltonian operator is given by

, which represents the total energy of the system. In nonrelativistic quantum mechanics the nonrelativistic Hamiltonian operator is given by  .

. - The momentum operator

is given by

is given by  (in the position basis), or

(in the position basis), or  (in the momentum basis).

(in the momentum basis). - The position operator

is given by

is given by  (in the position basis), or

(in the position basis), or  (in the momentum basis).

(in the momentum basis).

Operators can be noncommuting. Two Hermitian operators commute if (and only if) there is at least one basis of vectors such that each of which is an eigenvector of both operators (this is sometimes called a simultaneous eigenbasis). Noncommuting observables are said to be incompatible and cannot in general be measured simultaneously. In fact, they are related by an uncertainty principle as discovered by Werner Heisenberg.

Measurement probabilities and wavefunction collapse

There are a few possible ways to mathematically describe the measurement process (both the probability distribution and the collapsed wavefunction). The most convenient description depends on the spectrum (i.e., set of eigenvalues) of the observable.

Discrete, nondegenerate spectrum

Let  be an observable. By assumption,

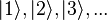

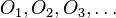

be an observable. By assumption,  has discrete eigenstates

has discrete eigenstates  with corresponding distinct eigenvalues

with corresponding distinct eigenvalues  . That is, the states are nondegenerate.

. That is, the states are nondegenerate.

Consider a system prepared in state  . Since the eigenstates of the observable

. Since the eigenstates of the observable  form a complete basis called eigenbasis, the state vector

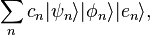

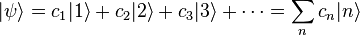

form a complete basis called eigenbasis, the state vector  can be written in terms of the eigenstates as

can be written in terms of the eigenstates as

,

,

where  are complex numbers in general. The eigenvalues

are complex numbers in general. The eigenvalues  are all possible values of the measurement. The corresponding probabilities are given by

are all possible values of the measurement. The corresponding probabilities are given by

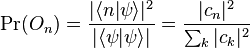

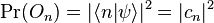

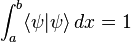

Usually  is assumed to be normalized, i.e.

is assumed to be normalized, i.e.  . Therefore, the expression above is reduced to

. Therefore, the expression above is reduced to

If the result of the measurement is  , then the system (after measurement) is in pure state

, then the system (after measurement) is in pure state  . That is,

. That is,

so any repeated measurement of  will yield the same result

will yield the same result  .

When there is a discontinuous change in state due to a measurement that involves discrete eigenvalues, that is called wavefunction collapse. For some, this is simply a description of a reasonably accurate discontinuous change in a mathematical representation of physical reality; for others, depending on philosophical orientation, this is a fundamentally serious problem with quantum theory; others see this as statistically-justified approximation resulting from the fact that the entity performing this measurement has been excluded from the state-representation. In particular, multiple measurements of certain physically extended systems demonstrate predicted statistical correlations which would not be possible under classical assumptions.

.

When there is a discontinuous change in state due to a measurement that involves discrete eigenvalues, that is called wavefunction collapse. For some, this is simply a description of a reasonably accurate discontinuous change in a mathematical representation of physical reality; for others, depending on philosophical orientation, this is a fundamentally serious problem with quantum theory; others see this as statistically-justified approximation resulting from the fact that the entity performing this measurement has been excluded from the state-representation. In particular, multiple measurements of certain physically extended systems demonstrate predicted statistical correlations which would not be possible under classical assumptions.

Continuous, nondegenerate spectrum

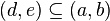

Let  be an observable. By assumption,

be an observable. By assumption,  has continuous eigenstate

has continuous eigenstate  , with corresponding distinct eigenvalue

, with corresponding distinct eigenvalue  . The eigenvalue forms a continuous spectrum filling the interval (a,b).

. The eigenvalue forms a continuous spectrum filling the interval (a,b).

Consider a system prepared in state  . Since the eigenstates of the observable

. Since the eigenstates of the observable  form a complete basis called eigenbasis, the state vector

form a complete basis called eigenbasis, the state vector  can be written in terms of the eigenstates as

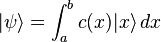

can be written in terms of the eigenstates as

,

,

where  is a complex-valued function. The eigenvalue that fills up the interval

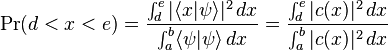

is a complex-valued function. The eigenvalue that fills up the interval  is the possible value of measurement. The corresponding probability is described by a probability function given by

is the possible value of measurement. The corresponding probability is described by a probability function given by

where  . Usually

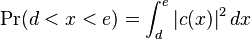

. Usually  is assumed to be normalized, i.e.

is assumed to be normalized, i.e.  . Therefore, the expression above is reduced to

. Therefore, the expression above is reduced to

If the result of the measurement is  , then the system (after measurement) is in pure state

, then the system (after measurement) is in pure state  . That is,

. That is,

Alternatively, it is often possible and convenient to analyze a continuous-spectrum measurement by taking it to be the limit of a different measurement with a discrete spectrum. For example, an analysis of scattering involves a continuous spectrum of energies, but by adding a "box" potential (which bounds the volume in which the particle can be found), the spectrum becomes discrete. By considering larger and larger boxes, this approach need not involve any approximation, but rather can be regarded as an equally valid formalism in which this problem can be analyzed.

Degenerate spectra

If there are multiple eigenstates with the same eigenvalue (called degeneracies), the analysis is a bit less simple to state, but not essentially different. In the discrete case, for example, instead of finding a complete eigenbasis, it is a bit more convenient to write the Hilbert space as a direct sum of multiple eigenspaces. The probability of measuring a particular eigenvalue is the squared component of the state vector in the corresponding eigenspace, and the new state after measurement is the projection of the original state vector into the appropriate eigenspace.

Density matrix formulation

Instead of performing quantum-mechanics computations in terms of wavefunctions (kets), it is sometimes necessary to describe a quantum-mechanical system in terms of a density matrix. The analysis in this case is formally slightly different, but the physical content is the same, and indeed this case can be derived from the wavefunction formulation above. The result for the discrete, degenerate case, for example, is as follows:

Let  be an observable, and suppose that it has discrete eigenvalues

be an observable, and suppose that it has discrete eigenvalues  , associated with eigenspaces

, associated with eigenspaces  respectively. Let

respectively. Let  be the projection operator into the space

be the projection operator into the space  .

.

Assume the system is prepared in the state described by the density matrix ρ. Then measuring  can yield any of the results

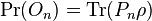

can yield any of the results  , with corresponding probabilities given by

, with corresponding probabilities given by

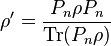

where  denotes trace. If the result of the measurement is n, then the new density matrix will be

denotes trace. If the result of the measurement is n, then the new density matrix will be

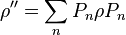

Alternatively, one can say that the measurement process results in the new density matrix

where the difference is that  is the density matrix describing the entire ensemble, whereas

is the density matrix describing the entire ensemble, whereas  is the density matrix describing the sub-ensemble whose measurement result was

is the density matrix describing the sub-ensemble whose measurement result was  .

.

Statistics of measurement

As detailed above, the result of measuring a quantum-mechanical system is described by a probability distribution. Some properties of this distribution are as follows:

Suppose we take a measurement corresponding to observable  , on a state whose quantum state is

, on a state whose quantum state is  .

.

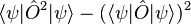

- The mean (average) value of the measurement is

-

(see expectation value).

(see expectation value).

-

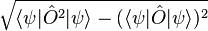

- The variance of the measurement is

- The standard deviation of the measurement is

These are direct consequences of the above formulas for measurement probabilities.

Example

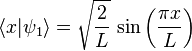

Suppose that we have a particle in a 1-dimensional box, set up initially in the ground state  . As can be computed from the time-independent Schrödinger equation, the energy of this state is

. As can be computed from the time-independent Schrödinger equation, the energy of this state is  (where m is the particle's mass and L is the box length), and the spatial wavefunction is

(where m is the particle's mass and L is the box length), and the spatial wavefunction is  . If the energy is now measured, the result will always certainly be

. If the energy is now measured, the result will always certainly be  , and this measurement will not affect the wavefunction.

, and this measurement will not affect the wavefunction.

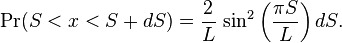

Next suppose that the particle's position is measured. The position x will be measured with probability density

If the measurement result was x=S, then the wavefunction after measurement will be the position eigenstate  . If the particle's position is immediately measured again, the same position will be obtained.

. If the particle's position is immediately measured again, the same position will be obtained.

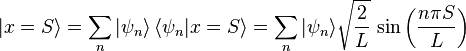

The new wavefunction  can, like any wavefunction, be written as a superposition of eigenstates of any observable. In particular, using energy eigenstates,

can, like any wavefunction, be written as a superposition of eigenstates of any observable. In particular, using energy eigenstates,  , we have

, we have

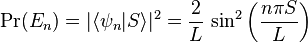

If we now leave this state alone, it will smoothly evolve in time according to the Schrödinger equation. But suppose instead that an energy measurement is immediately taken. Then the possible energy values  will be measured with relative probabilities:

will be measured with relative probabilities:

and moreover if the measurement result is  , then the new state will be the energy eigenstate

, then the new state will be the energy eigenstate  .

.

So in this example, due to the process of wavefunction collapse, a particle initially in the ground state can end up in any energy level, after just two subsequent non-commuting measurements are made.

Wavefunction collapse

The process in which a quantum state becomes one of the eigenstates of the operator corresponding to the measured observable is called "collapse", or "wavefunction collapse". The final eigenstate appears randomly with a probability equal to the square of its overlap with the original state.[2] The process of collapse has been studied in many experiments, most famously in the double-slit experiment. The wavefunction collapse raises serious questions regarding "the measurement problem",[3] as well as questions of determinism and locality, as demonstrated in the EPR paradox and later in GHZ entanglement. (See below.)

In the last few decades, major advances have been made toward a theoretical understanding of the collapse process. This new theoretical framework, called quantum decoherence, supersedes previous notions of instantaneous collapse and provides an explanation for the absence of quantum coherence after measurement. Decoherence correctly predicts the form and probability distribution of the final eigenstates, and explains the apparent randomness of the choice of final state in terms of einselection.[4]

von Neumann measurement scheme

The von Neumann measurement scheme, the ancestor of quantum decoherence theory, describes measurements by taking into account the measuring apparatus which is also treated as a quantum object.

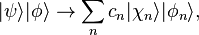

"Measurement" of the first kind — premeasurement without detection

Let the quantum state be in the superposition  , where

, where  are eigenstates of the operator for the so-called "measurement" prior to von Neumann's second apparatus. In order to make the "measurement", the system described by

are eigenstates of the operator for the so-called "measurement" prior to von Neumann's second apparatus. In order to make the "measurement", the system described by  needs to interact with the measuring apparatus described by the quantum state

needs to interact with the measuring apparatus described by the quantum state  , so that the total wave function before the measurement and interaction with the second apparatus is

, so that the total wave function before the measurement and interaction with the second apparatus is  . During the interaction of object and measuring instrument the unitary evolution is supposed to realize the following transition from the initial to the final total wave function:

. During the interaction of object and measuring instrument the unitary evolution is supposed to realize the following transition from the initial to the final total wave function:

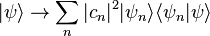

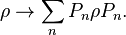

where  are orthonormal states of the measuring apparatus. The unitary evolution above is referred to as premeasurement. The relation with wave function collapse is established by calculating the final density operator of the object

are orthonormal states of the measuring apparatus. The unitary evolution above is referred to as premeasurement. The relation with wave function collapse is established by calculating the final density operator of the object  from the final total wave function. This density operator is interpreted by von Neumann as describing an ensemble of objects being after the measurement with probability

from the final total wave function. This density operator is interpreted by von Neumann as describing an ensemble of objects being after the measurement with probability  in the state

in the state

The transition

is often referred to as weak von Neumann projection, the wave function collapse or strong von Neumann projection

being thought to correspond to an additional selection of a subensemble by means of observation.

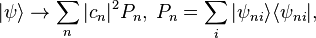

In case the measured observable has a degenerate spectrum, weak von Neumann projection is generalized to Lüders projection

in which the vectors  for fixed n are the degenerate eigenvectors of the measured observable. For an arbitrary state described by a density operator

for fixed n are the degenerate eigenvectors of the measured observable. For an arbitrary state described by a density operator

Lüders projection is given by

Lüders projection is given by

Measurement of the second kind — with irreversible detection

In a measurement of the second kind the unitary evolution during the interaction of object and measuring instrument is supposed to be given by

in which the states  of the object are determined by specific properties of the interaction between object and measuring instrument. They are normalized but not necessarily mutually orthogonal. The relation with wave function collapse is analogous to that obtained for measurements of the first kind, the final state of the object now being

of the object are determined by specific properties of the interaction between object and measuring instrument. They are normalized but not necessarily mutually orthogonal. The relation with wave function collapse is analogous to that obtained for measurements of the first kind, the final state of the object now being  with probability

with probability  Note that many measurement procedures are measurements of the second kind, some even functioning correctly only as a consequence of being of the second kind. For instance, a photon counter, detecting a photon by absorbing and hence annihilating it, thus ideally leaving the electromagnetic field in the vacuum state rather than in the state corresponding to the number of detected photons; also the Stern–Gerlach experiment would not function at all if it really were a measurement of the first kind.[5]

Note that many measurement procedures are measurements of the second kind, some even functioning correctly only as a consequence of being of the second kind. For instance, a photon counter, detecting a photon by absorbing and hence annihilating it, thus ideally leaving the electromagnetic field in the vacuum state rather than in the state corresponding to the number of detected photons; also the Stern–Gerlach experiment would not function at all if it really were a measurement of the first kind.[5]

Decoherence in quantum measurement

One can also introduce the interaction with the environment  , so that, in a measurement of the first kind, after the interaction the total wave function takes a form

, so that, in a measurement of the first kind, after the interaction the total wave function takes a form

which is related to the phenomenon of decoherence.

The above is completely described by the Schrödinger equation and there are not any interpretational problems with this. Now the problematic wavefunction collapse does not need to be understood as a process  on the level of the measured system, but can also be understood as a process

on the level of the measured system, but can also be understood as a process  on the level of the measuring apparatus, or as a process

on the level of the measuring apparatus, or as a process  on the level of the environment. Studying these processes provides considerable insight into the measurement problem by avoiding the arbitrary boundary between the quantum and classical worlds, though it does not explain the presence of randomness in the choice of final eigenstate. If the set of states

on the level of the environment. Studying these processes provides considerable insight into the measurement problem by avoiding the arbitrary boundary between the quantum and classical worlds, though it does not explain the presence of randomness in the choice of final eigenstate. If the set of states

,

,  , or

, or

represents a set of states that do not overlap in space, the appearance of collapse can be generated by either the Bohm interpretation or the Everett interpretation which both deny the reality of wavefunction collapse. Both of these are stated to predict the same probabilities for collapses to various states as the conventional interpretation by their supporters. The Bohm interpretation is held to be correct only by a small minority of physicists, since there are difficulties with the generalization for use with relativistic quantum field theory. However, there is no proof that the Bohm interpretation is inconsistent with quantum field theory, and work to reconcile the two is ongoing. The Everett interpretation easily accommodates relativistic quantum field theory.

Philosophical problems of quantum measurements

What physical interaction constitutes a measurement?

Until the advent of quantum decoherence theory in the late 20th century, a major conceptual problem of quantum mechanics and especially the Copenhagen interpretation was the lack of a distinctive criterion for a given physical interaction to qualify as "a measurement" and cause a wavefunction to collapse. This is illustrated by the Schrödinger's cat paradox. Certain aspects of this question are now well understood in the framework of quantum decoherence theory, such as an understanding of weak measurements, and quantifying what measurements or interactions are sufficient to destroy quantum coherence. Nevertheless, there remains less than universal agreement among physicists on some aspects of the question of what constitutes a measurement.

Does measurement actually determine the state?

The question of whether (and in what sense) a measurement actually determines the state is one which differs among the different interpretations of quantum mechanics. (It is also closely related to the understanding of wavefunction collapse.) For example, in most versions of the Copenhagen interpretation, the measurement determines the state, and after measurement the state is definitely what was measured. But according to the many-worlds interpretation, measurement determines the state in a more restricted sense: In other "worlds", other measurement results were obtained, and the other possible states still exist.

Is the measurement process random or deterministic?

As described above, there is universal agreement that quantum mechanics appears random, in the sense that all experimental results yet uncovered can be predicted and understood in the framework of quantum mechanics measurements being fundamentally random. Nevertheless, it is not settled[6] whether this is true, fundamental randomness, or merely "emergent" randomness resulting from underlying hidden variables which deterministically cause measurement results to happen a certain way each time. This continues to be an area of active research.[7]

If there are hidden variables, they would have to be "nonlocal".

Does the measurement process violate locality?

In physics, the Principle of locality is the concept that information cannot travel faster than the speed of light (also see special relativity). It is known experimentally (see Bell's theorem, which is related to the EPR paradox) that if quantum mechanics is deterministic (due to hidden variables, as described above), then it is nonlocal (i.e. violates the principle of locality). Nevertheless, there is not universal agreement among physicists on whether quantum mechanics is nondeterministic, nonlocal, or both.[6]

See also

- Measurement related problems and paradoxes

- Interpretations of quantum mechanics

- Quantum mechanics formalism

- Quantum mechanics

- Mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics

- Schrödinger equation

- Bra-ket notation

- Generalized measurement (POVM, Positive operator valued measure)

References

- ↑ Hermann Wimmel (1992). Quantum physics & observed reality: a critical interpretation of quantum mechanics. World Scientific. p. 2. ISBN 978-981-02-1010-6. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- 1 2 J. J. Sakurai (1994). Modern Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). ISBN 0201539292.

- ↑ George S. Greenstein and Arthur G. Zajonc (2006). The Quantum Challenge: Modern Research On The Foundations Of Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). ISBN 076372470X.

- ↑ Wojciech H. Zurek, Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical,Reviews of Modern Physics 2003, 75, 715 or http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0105127

- ↑ M.O. Scully, W.E. Lamb, A. Barut (1987). "On the theory of the Stern–Gerlach apparatus" (PDF). Foundations of Physics 17: 575–583. Bibcode:1987FoPh...17..575S. doi:10.1007/BF01882788. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- 1 2 Hrvoje Nikolić (2007). "Quantum mechanics: Myths and facts". Foundation of Physics 37: 1563–1611. arXiv:quant-ph/0609163. Bibcode:2007FoPh...37.1563N. doi:10.1007/s10701-007-9176-y.

- ↑ S. Gröblacher; et al. (2007). "An experimental test of non-local realism". Nature 446 (871): 871–5. arXiv:0704.2529. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..871G. doi:10.1038/nature05677. PMID 17443179.

Further reading

- John A. Wheeler and Wojciech Hubert Zurek, eds. (1983). Quantum Theory and Measurement. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08316-9.

- Vladimir B. Braginsky and Farid Ya. Khalili (1992). Quantum Measurement. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41928-X.

- George S. Greenstein and Arthur G. Zajonc (2006). The Quantum Challenge: Modern Research On The Foundations Of Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). ISBN 076372470X.

External links

- "The Double Slit Experiment". (physicsweb.org)

- "Measurement in Quantum Mechanics" Henry Krips in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Decoherence, the measurement problem, and interpretations of quantum mechanics

- Measurements and Decoherence

- The conditions for discrimination between quantum states with minimum error

- Quantum behavior of measurement apparatus