Quantum superposition

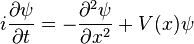

Quantum superposition is a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics. It states that much like waves in classical physics, any two (or more) quantum states can be added together ("superposed") and the result will be another valid quantum state; and conversely, that every quantum state can be represented as a sum of two or more other distinct states. Mathematically, it refers to a property of solutions to the Schrödinger equation; since the Schrödinger equation is linear, any linear combination of solutions will also be a solution.

An example of a physically observable manifestation of superposition is interference peaks from an electron wave in a double-slit experiment.

Another example is a quantum logical qubit state, as used in quantum information processing, which is a linear superposition of the "basis states"  and

and  .

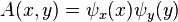

Here

.

Here  is the Dirac notation for the quantum state that will always give the result 0 when converted to classical logic by a measurement. Likewise

is the Dirac notation for the quantum state that will always give the result 0 when converted to classical logic by a measurement. Likewise  is the state that will always convert to 1.

is the state that will always convert to 1.

Theory

Examples

For an equation describing a physical phenomenon, the superposition principle states that a combination of solutions to a linear equation is also a solution of it. When this is true the equation is said to obey the superposition principle. Thus if state vectors f1, f2 and f3 each solve the linear equation on ψ, then ψ = c1 f1 + c2 f2 + c3 f3 would also be a solution, in which each c is a coefficient. The Schrödinger equation is linear, so quantum mechanics follows this.

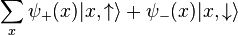

For example, consider an electron with two possible configurations, up and down. This describes the physical system of a qubit.

is the most general state. But these coefficients dictate probabilities for the system to be in either configuration. The probability for a specified configuration is given by the square of the absolute value of the coefficient. So the probabilities should add up to 1. The electron is in one of those two states for sure.

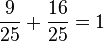

Continuing with this example: If a particle can be in state up and down, it can also be in a state where it is an amount 3i/5 in up and an amount 4/5 in down.

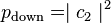

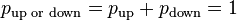

In this, the probability for up is  . The probability for down is

. The probability for down is  . Note that

. Note that  .

.

In the description, only the relative size of the different components matter, and their angle to each other on the complex plane. This is usually stated by declaring that two states which are a multiple of one another are the same as far as the description of the situation is concerned. Either of these describe the same state for any nonzero

The fundamental law of quantum mechanics is that the evolution is linear, meaning that if state A turns into A′ and B turns into B′ after 10 seconds, then after 10 seconds the superposition  turns into a mixture of A′ and B′ with the same coefficients as A and B.

turns into a mixture of A′ and B′ with the same coefficients as A and B.

For example, if we have the following

Then after those 10 seconds our state will change to

So far there have just been 2 configurations, but there can be infinitely many.

In illustration, a particle can have any position, so that there are different configurations which have any value of the position x. These are written:

The principle of superposition guarantees that there are states which are arbitrary superpositions of all the positions with complex coefficients:

This sum is defined only if the index x is discrete. If the index is over  , then the sum replaced by an integral. The quantity

, then the sum replaced by an integral. The quantity  is called the wavefunction of the particle.

is called the wavefunction of the particle.

If we consider a qubit with both position and spin, the state is a superposition of all possibilities for both:

The configuration space of a quantum mechanical system cannot be worked out without some physical knowledge. The input is usually the allowed different classical configurations, but without the duplication of including both position and momentum.

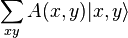

A pair of particles can be in any combination of pairs of positions. A state where one particle is at position x and the other is at position y is written  . The most general state is a superposition of the possibilities:

. The most general state is a superposition of the possibilities:

The description of the two particles is much larger than the description of one particle—it is a function in twice the number of dimensions. This is also true in probability, when the statistics of two random variables are correlated. If two particles are uncorrelated, the probability distribution for their joint position P(x, y) is a product of the probability of finding one at one position and the other at the other position:

In quantum mechanics, two particles can be in special states where the amplitudes of their position are uncorrelated. For quantum amplitudes, the word entanglement replaces the word correlation, but the analogy is exact. A disentangled wave function has the form:

while an entangled wavefunction does not have this form.

Analogy with probability

In probability theory there is a similar principle. If a system has a probabilistic description, this description gives the probability of any particular configuration, and given any two different configurations, there is a state which is partly this and partly that, with positive real number coefficients, the probabilities, which say how much of each there is.

For example, if we have a probability distribution for where a particle is, it is described by the "state"

Where  is the probability density function, a positive number that measures the probability that the particle will be found at a certain location.

is the probability density function, a positive number that measures the probability that the particle will be found at a certain location.

The evolution equation is also linear in probability, for fundamental reasons. If the particle has some probability for going from position x to y, and from z to y, the probability of going to y starting from a state which is half-x and half-z is a half-and-half mixture of the probability of going to y from each of the options. This is the principle of linear superposition in probability.

Quantum mechanics is different, because the numbers can be positive or negative. While the complex nature of the numbers is just a doubling, if you consider the real and imaginary parts separately, the sign of the coefficients is important. In probability, two different possible outcomes always add together, so that if there are more options to get to a point z, the probability always goes up. In quantum mechanics, different possibilities can cancel.

In probability theory with a finite number of states, the probabilities can always be multiplied by a positive number to make their sum equal to one. For example, if there is a three state probability system:

where the probabilities  are positive numbers. Rescaling x,y,z so that

are positive numbers. Rescaling x,y,z so that

The geometry of the state space is a revealed to be a triangle. In general it is a simplex. There are special points in a triangle or simplex corresponding to the corners, and these points are those where one of the probabilities is equal to 1 and the others are zero. These are the unique locations where the position is known with certainty.

In a quantum mechanical system with three states, the quantum mechanical wavefunction is a superposition of states again, but this time twice as many quantities with no restriction on the sign:

rescaling the variables so that the sum of the squares is 1, the geometry of the space is revealed to be a high-dimensional sphere

.

.

A sphere has a large amount of symmetry, it can be viewed in different coordinate systems or bases. So unlike a probability theory, a quantum theory has a large number of different bases in which it can be equally well described. The geometry of the phase space can be viewed as a hint that the quantity in quantum mechanics which corresponds to the probability is the absolute square of the coefficient of the superposition.

Hamiltonian evolution

The numbers that describe the amplitudes for different possibilities define the kinematics, the space of different states. The dynamics describes how these numbers change with time. For a particle that can be in any one of infinitely many discrete positions, a particle on a lattice, the superposition principle tells you how to make a state:

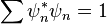

So that the infinite list of amplitudes  completely describes the quantum state of the particle. This list is called the state vector, and formally it is an element of a Hilbert space, an infinite dimensional complex vector space. It is usual to represent the state so that the sum of the absolute squares of the amplitudes add up to one:

completely describes the quantum state of the particle. This list is called the state vector, and formally it is an element of a Hilbert space, an infinite dimensional complex vector space. It is usual to represent the state so that the sum of the absolute squares of the amplitudes add up to one:

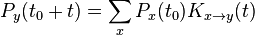

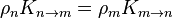

For a particle described by probability theory random walking on a line, the analogous thing is the list of probabilities  , which give the probability of any position. The quantities that describe how they change in time are the transition probabilities

, which give the probability of any position. The quantities that describe how they change in time are the transition probabilities  , which gives the probability that, starting at x, the particle ends up at y after time t. The total probability of ending up at y is given by the sum over all the possibilities

, which gives the probability that, starting at x, the particle ends up at y after time t. The total probability of ending up at y is given by the sum over all the possibilities

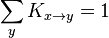

The condition of conservation of probability states that starting at any x, the total probability to end up somewhere must add up to 1:

So that the total probability will be preserved, K is what is called a stochastic matrix.

When no time passes, nothing changes: for zero elapsed time  , the K matrix is zero except from a state to itself. So in the case that the time is short, it is better to talk about the rate of change of the probability instead of the absolute change in the probability.

, the K matrix is zero except from a state to itself. So in the case that the time is short, it is better to talk about the rate of change of the probability instead of the absolute change in the probability.

where  is the time derivative of the K matrix:

is the time derivative of the K matrix:

.

.

The equation for the probabilities is a differential equation which is sometimes called the master equation:

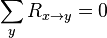

The R matrix is the probability per unit time for the particle to make a transition from x to y. The condition that the K matrix elements add up to one becomes the condition that the R matrix elements add up to zero:

One simple case to study is when the R matrix has an equal probability to go one unit to the left or to the right, describing a particle which has a constant rate of random walking. In this case  is zero unless y is either x+1,x, or x−1, when y is x+1 or x−1, the R matrix has value c, and in order for the sum of the R matrix coefficients to equal zero, the value of

is zero unless y is either x+1,x, or x−1, when y is x+1 or x−1, the R matrix has value c, and in order for the sum of the R matrix coefficients to equal zero, the value of  must be −2c. So the probabilities obey the discretized diffusion equation:

must be −2c. So the probabilities obey the discretized diffusion equation:

which, when c is scaled appropriately and the P distribution is smooth enough to think of the system in a continuum limit becomes:

Which is the diffusion equation.

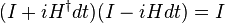

Quantum amplitudes give the rate at which amplitudes change in time, and they are mathematically exactly the same except that they are complex numbers. The analog of the finite time K matrix is called the U matrix:

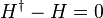

Since the sum of the absolute squares of the amplitudes must be constant,  must be unitary:

must be unitary:

or, in matrix notation,

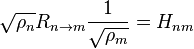

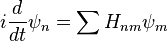

The rate of change of U is called the Hamiltonian H, up to a traditional factor of i:

The Hamiltonian gives the rate at which the particle has an amplitude to go from m to n. The reason it is multiplied by i is that the condition that U is unitary translates to the condition:

which says that H is Hermitian. The eigenvalues of the Hermitian matrix H are real quantities which have a physical interpretation as energy levels. If the factor i were absent, the H matrix would be antihermitian and would have purely imaginary eigenvalues, which is not the traditional way quantum mechanics represents observable quantities like the energy.

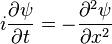

For a particle which has equal amplitude to move left and right, the Hermitian matrix H is zero except for nearest neighbors, where it has the value c. If the coefficient is everywhere constant, the condition that H is Hermitian demands that the amplitude to move to the left is the complex conjugate of the amplitude to move to the right. The equation of motion for  is the time differential equation:

is the time differential equation:

In the case that left and right are symmetric, c is real. By redefining the phase of the wavefunction in time,  , the amplitudes for being at different locations are only rescaled, so that the physical situation is unchanged. But this phase rotation introduces a linear term.

, the amplitudes for being at different locations are only rescaled, so that the physical situation is unchanged. But this phase rotation introduces a linear term.

which is the right choice of phase to take the continuum limit. When c is very large and psi is slowly varying so that the lattice can be thought of as a line, this becomes the free Schrödinger equation:

If there is an additional term in the H matrix which is an extra phase rotation which varies from point to point, the continuum limit is the Schrödinger equation with a potential energy:

These equations describe the motion of a single particle in non-relativistic quantum mechanics.

Quantum mechanics in imaginary time

The analogy between quantum mechanics and probability is very strong, so that there are many mathematical links between them. In a statistical system in discrete time, t=1,2,3, described by a transition matrix for one time step  , the probability to go between two points after a finite number of time steps can be represented as a sum over all paths of the probability of taking each path:

, the probability to go between two points after a finite number of time steps can be represented as a sum over all paths of the probability of taking each path:

where the sum extends over all paths  with the property that

with the property that  and

and  . The analogous expression in quantum mechanics is the path integral.

. The analogous expression in quantum mechanics is the path integral.

A generic transition matrix in probability has a stationary distribution, which is the eventual probability to be found at any point no matter what the starting point. If there is a nonzero probability for any two paths to reach the same point at the same time, this stationary distribution does not depend on the initial conditions. In probability theory, the probability m for the stochastic matrix obeys detailed balance when the stationary distribution  has the property:

has the property:

Detailed balance says that the total probability of going from m to n in the stationary distribution, which is the probability of starting at m  times the probability of hopping from m to n, is equal to the probability of going from n to m, so that the total back-and-forth flow of probability in equilibrium is zero along any hop. The condition is automatically satisfied when n=m, so it has the same form when written as a condition for the transition-probability R matrix.

times the probability of hopping from m to n, is equal to the probability of going from n to m, so that the total back-and-forth flow of probability in equilibrium is zero along any hop. The condition is automatically satisfied when n=m, so it has the same form when written as a condition for the transition-probability R matrix.

When the R matrix obeys detailed balance, the scale of the probabilities can be redefined using the stationary distribution so that they no longer sum to 1:

In the new coordinates, the R matrix is rescaled as follows:

and H is symmetric

This matrix H defines a quantum mechanical system:

whose Hamiltonian has the same eigenvalues as those of the R matrix of the statistical system. The eigenvectors are the same too, except expressed in the rescaled basis. The stationary distribution of the statistical system is the ground state of the Hamiltonian and it has energy exactly zero, while all the other energies are positive. If H is exponentiated to find the U matrix:

and t is allowed to take on complex values, the K' matrix is found by taking time imaginary.

For quantum systems which are invariant under time reversal the Hamiltonian can be made real and symmetric, so that the action of time-reversal on the wave-function is just complex conjugation. If such a Hamiltonian has a unique lowest energy state with a positive real wave-function, as it often does for physical reasons, it is connected to a stochastic system in imaginary time. This relationship between stochastic systems and quantum systems sheds much light on supersymmetry.

Experiments and applications

Successful experiments involving superpositions of relatively large (by the standards of quantum physics) objects have been performed.[1]

- A "cat state" has been achieved with photons.[2]

- A beryllium ion has been trapped in a superposed state.[3]

- A double slit experiment has been performed with molecules as large as buckyballs.[4][5]

- A 2013 experiment superposed molecules containing 15,000 each of protons, neutrons and electrons. The molecules were of compounds selected for their good thermal stability, and were evaporated into a beam at a temperature of 600 K. The beam was prepared from highly purified chemical substances, but still contained a mixture of different molecular species. Each species of molecule interfered only with itself, as verified by mass spectrometry.[6]

- An experiment involving a superconducting quantum interference device ("SQUID") has been linked to theme of the "cat state" thought experiment.[7]

- By use of very low temperatures, very fine experimental arrangements were made to protect in near isolation and preserve the coherence of intermediate states, for a duration of time, between preparation and detection, of SQUID currents. Such a SQUID current is a coherent physical assembly of perhaps billions of electrons. Because of its coherence, such an assembly may be regarded as exhibiting "collective states" of a macroscopic quantal entity. For the principle of superposition, after it is prepared but before it is detected, it may be regarded as exhibiting an intermediate state. It is not a single-particle state such as is often considered in discussions of interference, for example by Dirac in his famous dictum stated above.[8] Morever, though the 'intermediate' state may be loosely regarded as such, it has not been produced as an output of a secondary quantum analyser that was fed a pure state from a primary analyser, and so this is not an example of superposition as strictly and narrowly defined.

- Nevertheless, after preparation, but before measurement, such a SQUID state may be regarded in a manner of speaking as a "pure" state that is a superposition of a clockwise and an anti-clockwise current state. In a SQUID, collective electron states can be physically prepared in near isolation, at very low temperatures, so as to result in protected coherent intermediate states. Remarkable here is that there are found two well-separated respectively self-coherent collective states that exhibit such metastability. The crowd of electrons tunnels back and forth between the clockwise and the anti-clockwise states, as opposed to forming a single intermediate state in which there is no definite collective sense of current flow.[9][10]

- In contrast, for actual real cats, such well-separated metastable collective states states do not exist and consequently cannot be physically prepared. Schrödinger's point was that classical thinking does not in general anticipate such physically distinct and separate metastable quantum states. In classical thinking, distinct quantum states even of single atoms can indeed be regarded as metastable, and are remarkable and unexpected. In the days when Schrödinger raised his argumentative example, no one had imagined the invention of SQUIDs that exhibit such states on a macroscopic scale. The present-day physicist here pays close attention to the requirement mentioned above, that the intermediate states must be carefully physically shielded to protect them from any factor that affects some of the independent quantal entities (in this case collective not single particle) differently from others. Contrary to this requirement, the living cat breathes. This destroys intermediate state coherence, and so the conditions required for exhibition of the principle of superposition are not fulfilled.

- An experiment involving a flu virus has been proposed.[11]

- A piezoelectric "tuning fork" has been constructed, which can be placed into a superposition of vibrating and non vibrating states. The resonator comprises about 10 trillion atoms.[12]

- Recent research indicates that chlorophyll within plants appears to exploit the feature of quantum superposition to achieve greater efficiency in transporting energy, allowing pigment proteins to be spaced further apart than would otherwise be possible.[13][14]

- An experiment has been proposed, with a bacterial cell cooled to 10 mK, using an electromechanical oscillator.[15] At that temperature, all metabolism would be stopped, and the cell might behave virtually as a definite chemical species. For detection of interference, it would be necessary that the cells be supplied in large numbers as pure samples of identical and detectably recognizable virtual chemical species. It is not known whether this requirement can be met by bacterial cells. They would be in a state of suspended animation during the experiment.

In quantum computing the phrase "cat state" often refers to the special entanglement of qubits wherein the qubits are in an equal superposition of all being 0 and all being 1; i.e.,

.

.

Formal interpretation

Applying the superposition principle to a quantum mechanical particle, the configurations of the particle are all positions, so the superpositions make a complex wave in space. The coefficients of the linear superposition are a wave which describes the particle as best as is possible, and whose amplitude interferes according to the Huygens principle.

For any physical property in quantum mechanics, there is a list of all the states where that property has some value. These states are necessarily perpendicular to each other using the Euclidean notion of perpendicularity which comes from sums-of-squares length, except that they also must not be i multiples of each other. This list of perpendicular states has an associated value which is the value of the physical property. The superposition principle guarantees that any state can be written as a combination of states of this form with complex coefficients.

Write each state with the value q of the physical quantity as a vector in some basis  , a list of numbers at each value of n for the vector which has value q for the physical quantity. Now form the outer product of the vectors by multiplying all the vector components and add them with coefficients to make the matrix

, a list of numbers at each value of n for the vector which has value q for the physical quantity. Now form the outer product of the vectors by multiplying all the vector components and add them with coefficients to make the matrix

where the sum extends over all possible values of q. This matrix is necessarily symmetric because it is formed from the orthogonal states, and has eigenvalues q. The matrix A is called the observable associated to the physical quantity. It has the property that the eigenvalues and eigenvectors determine the physical quantity and the states which have definite values for this quantity.

Every physical quantity has a Hermitian linear operator associated to it, and the states where the value of this physical quantity is definite are the eigenstates of this linear operator. The linear combination of two or more eigenstates results in quantum superposition of two or more values of the quantity. If the quantity is measured, the value of the physical quantity will be random, with a probability equal to the square of the coefficient of the superposition in the linear combination. Immediately after the measurement, the state will be given by the eigenvector corresponding to the measured eigenvalue.

Physical interpretation

It is natural to ask why ordinary everyday "real" (macroscopic, Newtonian) objects and events do not seem empirically to display quantum mechanical features such as superposition. Indeed, this is sometimes regarded even as "mysterious", for example by Richard Feynman.[16] In 1935, Erwin Schrödinger devised a well-known thought experiment, now known as Schrödinger's cat, which highlighted the dissonance between quantum mechanics and Newtonian physics, where only one configuration occurs, although a configuration for a particle in Newtonian physics specifies both position and momentum.

Physically, according to Dirac, this is explained as follows. It is a logical truism that a single detection of a quantum system, observed alone, empirically considered, is not an example of a relation of several states. For the several states are not empirically defined when the quantum system is observed alone. It would therefore be nonsense to try to say that it, a single state, observed alone, empirically shows superposition. It is convenient to describe superposition for an original primary beam that consists of quantum systems in a pure state. Superposition is a relation of several states that are empirically defined when the original superposed beam is split by some diffractive object into several intermediate sub-beams, empirically observable by distinct particle detectors respectively in each. The detectors should be removed when it is desired to verify superposition by re-composition of the sub-beams back into the original pure state. The sub-beams can be considered in two ways. Either they can be considered as joint constituents of the primary beam, an expression of the original pure state. Or they can be considered as separate sub-beams, each respectively pure with respect to the diffractive object.[17][18] To produce sub-beams, the diffractive object must be characterized by an operator that does not commute with at least one of the operators that define the production of the pure state of the original primary beam. It is classically inexplicable how a quantum analyser or diffractive object can have several pure states as outputs. That is Feynman's "mystery".

Here may be found reason for differences of opinion, as between the Copenhagen or other interpretations. Neil Bohr famously insisted that the wave function refers to a single individual quantum system. What did he mean by this? He was expressing the idea that Dirac expressed when he famously wrote: "Each photon then interferes only with itself. Interference between different photons never occurs.".[19] Dirac clarified this by writing: "This, of course, is true only provided the two states that are superposed refer to the same beam of light, i.e. all that is known about the position and momentum of a photon in either of these states must be the same for each."[20] Bohr wanted to emphasize that a superposition is different from a mixture. He seemed to think that those who spoke of a "statistical interpretation" were not taking that into account. To create, by a superposition experiment, a new and different pure state, from an original pure beam, one can put absorbers and phase-shifters into some of the sub-beams, so as to alter the composition of the re-constituted superposition. But one cannot do so by mixing a fragment of the original unsplit beam with component split sub-beams. That is because one photon cannot both go into the unsplit fragment and go into the split component sub-beams. Bohr felt that talk in statistical terms might hide this fact.

Quantum superposition is exhibited in fact in many directly observable phenomena, such as interference peaks from an electron wave in a double-slit experiment. Superposition persists at all scales, provided that coherence is shielded from disruption by intermittent external factors.

The Heisenberg uncertainty principle states that for any given instant of time, the position and velocity of an electron or other subatomic particle cannot both be exactly determined.

If the operators corresponding to two observables do not commute, they have no simultaneous eigenstates and they obey the uncertainty principle. A state where one observable has a definite value corresponds to a superposition of many states for the other observable.

See also

- Eigenstates

- Mach-Zehnder interferometer

- Penrose Interpretation

- Pure qubit state

- Quantum computation

- Schrödinger's cat

- Wave packet

References

- ↑ What is the World's Biggest Schrodinger Cat?

- ↑ Schrödinger's Cat Now Made of Light

- ↑ C. Monroe, et. al. A "Schrodinger Cat" Superposition State of an Atom

- ↑ Wave Particle Duality of C60

- ↑ Diffraction of the Fullerenes C60 and C70 by a standing light wave

- ↑ Eibenberger, S., Gerlich, S., Arndt, M., Mayor, M., Tüxen, J. (2013). Matter-wave interference with particles selected from a molecular library with masses exceeding 10 000 amu, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 15: 14696-14700.

- ↑ Leggett, A.J. (1986). The superposition principle in macroscopic systems, pp. 28–40 in Quantum Concepts of Space and Time, edited by R. Penrose and C.J. Isham, ISBN 0-19-851972-9.

- ↑ Dirac, P.A.M. (1930/1958), p. 9.

- ↑ Physics World: Schrodinger's cat comes into view

- ↑ Friedman, J.R., Patel, V., Chen, W., Tolpygo, S.K., Lukens, J.E. (2000).Quantum superposition of distinct macroscopic states, Nature 406: 43–46.

- ↑ How to Create Quantum Superpositions of Living Things>

- ↑ Scientific American : Macro-Weirdness: "Quantum Microphone" Puts Naked-Eye Object in 2 Places at Once: A new device tests the limits of Schrödinger's cat

- ↑ Scholes, Gregory; Elisabetta Collini; Cathy Y. Wong; Krystyna E. Wilk; Paul M. G. Curmi; Paul Brumer; Gregory D. Scholes (4 February 2010). "Coherently wired light-harvesting in photosynthetic marine algae at ambient temperature". Nature 463 (7281): 644–647. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..644C. doi:10.1038/nature08811. PMID 20130647.

- ↑ Moyer, Michael (September 2009). "Quantum Entanglement, Photosynthesis and Better Solar Cells". Scientific American. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ↑ Could 'Schrödinger's bacterium' be placed in a quantum superposition?>

- ↑ Feynman, R.P., Leighton, R.B., Sands, M. (1965), § 1-1.

- ↑ Dirac, P.A.M. (1958). The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 4th edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford UK, p. 8: "For a photon to be in a definite translational state it need not be associated with one single beam of light, but may be associated with two or more beams of light which are the components into which one original beam has been split."

- ↑ Feynman, R.P., Leighton, R.B., Sands, M. (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Volume 3, Addison-Wesley, Reading MA, also here, Chapter 5, 'Spin One': "a filtered beam in a pure state with respect to S.

- ↑ Dirac, P.A.M., The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, (1930), 1st edition, p. 15; (1935), 2nd edition, p. 9; (1947), 3rd edition, p. 9; (1958), 4th edition, p. 9.

- ↑ Dirac, P.A.M., The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, (1930), 1st edition, p. 8.

Bibliography of cited references

- Bohr, N. (1927/1928). The quantum postulate and the recent development of atomic theory, Nature Supplement 14 April 1928, 121: 580–590.

- Cohen-Tannoudji, C., Diu, B., Laloë, F. (1973/1977). Quantum Mechanics, translated from the French by S.R. Hemley, N. Ostrowsky, D. Ostrowsky, second edition, volume 1, Wiley, New York, ISBN 0471164321.

- Dirac, P.A.M. (1930/1958). The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 4th edition, Oxford University Press.

- Einstein, A. (1949). Remarks concerning the essays brought together in this co-operative volume, translated from the original German by the editor, pp. 665–688 in Schilpp, P.A. editor (1949), Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, volume II, Open Court, La Salle IL.

- Feynman, R.P., Leighton, R.B., Sands, M. (1965). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, volume 3, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

- Merzbacher, E. (1961/1970). Quantum Mechanics, second edition, Wiley, New York.

- Messiah, A. (1961). Quantum Mechanics, volume 1, translated by G.M. Temmer from the French Mécanique Quantique, North-Holland, Amsterdam.

- Wheeler, J.A.; Zurek, W.H. (1983). Quantum Theory and Measurement. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.