Hamiltonian (quantum mechanics)

In quantum mechanics, the Hamiltonian is the operator corresponding to the total energy of the system in most of the cases. It is usually denoted by H, also Ȟ or Ĥ. Its spectrum is the set of possible outcomes when one measures the total energy of a system. Because of its close relation to the time-evolution of a system, it is of fundamental importance in most formulations of quantum theory.

The Hamiltonian is named after Sir William Rowan Hamilton (1805–1865), an Irish physicist, astronomer, and mathematician, best known for his reformulation of Newtonian mechanics, now called Hamiltonian mechanics.

Introduction

The Hamiltonian is the sum of the kinetic energies of all the particles, plus the potential energy of the particles associated with the system. For different situations or number of particles, the Hamiltonian is different since it includes the sum of kinetic energies of the particles, and the potential energy function corresponding to the situation.

The Schrödinger Hamiltonian

One particle

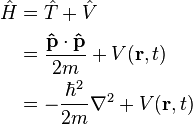

By analogy with classical mechanics, the Hamiltonian is commonly expressed as the sum of operators corresponding to the kinetic and potential energies of a system in the form

where

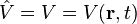

is the potential energy operator and

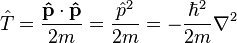

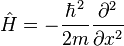

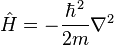

is the kinetic energy operator in which m is the mass of the particle, the dot denotes the dot product of vectors, and

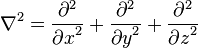

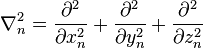

is the momentum operator wherein ∇ is the del operator. The dot product of ∇ with itself is the Laplacian ∇2. In three dimensions using Cartesian coordinates the Laplace operator is

Although this is not the technical definition of the Hamiltonian in classical mechanics, it is the form it most commonly takes. Combining these together yields the familiar form used in the Schrödinger equation:

which allows one to apply the Hamiltonian to systems described by a wave function Ψ(r, t). This is the approach commonly taken in introductory treatments of quantum mechanics, using the formalism of Schrödinger's wave mechanics.

One can also make substitutions to certain variables to fit specific cases, such as some involving electromagnetic fields.

Many particles

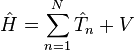

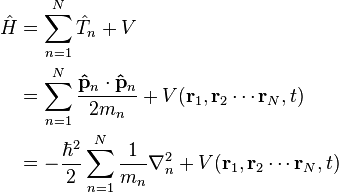

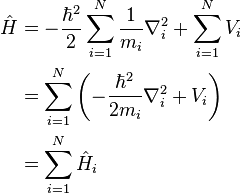

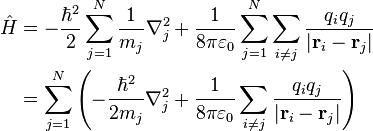

The formalism can be extended to N particles:

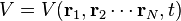

where

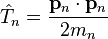

is the potential energy function, now a function of the spatial configuration of the system and time (a particular set of spatial positions at some instant of time defines a configuration) and;

is the kinetic energy operator of particle n, and ∇n is the gradient for particle n, ∇n2 is the Laplacian for particle using the coordinates:

Combining these yields the Schrödinger Hamiltonian for the N-particle case:

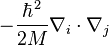

However, complications can arise in the many-body problem. Since the potential energy depends on the spatial arrangement of the particles, the kinetic energy will also depend on the spatial configuration to conserve energy. The motion due to any one particle will vary due to the motion of all the other particles in the system. For this reason cross terms for kinetic energy may appear in the Hamiltonian; a mix of the gradients for two particles:

where M denotes the mass of the collection of particles resulting in this extra kinetic energy. Terms of this form are known as mass polarization terms, and appear in the Hamiltonian of many electron atoms (see below).

For N interacting particles, i.e. particles which interact mutually and constitute a many-body situation, the potential energy function V is not simply a sum of the separate potentials (and certainly not a product, as this is dimensionally incorrect). The potential energy function can only be written as above: a function of all the spatial positions of each particle.

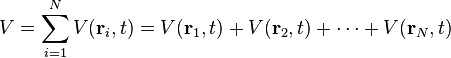

For non-interacting particles, i.e. particles which do not interact mutually and move independently, the potential of the system is the sum of the separate potential energy for each particle,[1] that is

The general form of the Hamiltonian in this case is:

where the sum is taken over all particles and their corresponding potentials; the result is that the Hamiltonian of the system is the sum of the separate Hamiltonians for each particle. This is an idealized situation - in practice the particles are usually always influenced by some potential, and there are many-body interactions. One illustrative example of a two-body interaction where this form would not apply is for electrostatic potentials due to charged particles, because they interact with each other by Coulomb interaction (electrostatic force), as shown below.

Schrödinger equation

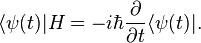

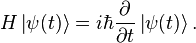

The Hamiltonian generates the time evolution of quantum states. If  is the state of the system at time t, then

is the state of the system at time t, then

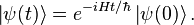

This equation is the Schrödinger equation. It takes the same form as the Hamilton–Jacobi equation, which is one of the reasons H is also called the Hamiltonian. Given the state at some initial time (t = 0), we can solve it to obtain the state at any subsequent time. In particular, if H is independent of time, then

The exponential operator on the right hand side of the Schrödinger equation is usually defined by the corresponding power series in H. One might notice that taking polynomials or power series of unbounded operators that are not defined everywhere may not make mathematical sense. Rigorously, to take functions of unbounded operators, a functional calculus is required. In the case of the exponential function, the continuous, or just the holomorphic functional calculus suffices. We note again, however, that for common calculations the physicists' formulation is quite sufficient.

By the *-homomorphism property of the functional calculus, the operator

is a unitary operator. It is the time evolution operator, or propagator, of a closed quantum system. If the Hamiltonian is time-independent, {U(t)} form a one parameter unitary group (more than a semigroup); this gives rise to the physical principle of detailed balance.

Dirac formalism

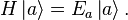

However, in the more general formalism of Dirac, the Hamiltonian is typically implemented as an operator on a Hilbert space in the following way:

The eigenkets (eigenvectors) of H, denoted  , provide an orthonormal basis for the Hilbert space. The spectrum of allowed energy levels of the system is given by the set of eigenvalues, denoted {Ea}, solving the equation:

, provide an orthonormal basis for the Hilbert space. The spectrum of allowed energy levels of the system is given by the set of eigenvalues, denoted {Ea}, solving the equation:

Since H is a Hermitian operator, the energy is always a real number.

From a mathematically rigorous point of view, care must be taken with the above assumptions. Operators on infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces need not have eigenvalues (the set of eigenvalues does not necessarily coincide with the spectrum of an operator). However, all routine quantum mechanical calculations can be done using the physical formulation.

Expressions for the Hamiltonian

Following are expressions for the Hamiltonian in a number of situations.[2] Typical ways to classify the expressions are the number of particles, number of dimensions, and the nature of the potential energy function - importantly space and time dependence. Masses are denoted by m, and charges by q.

Free particle

The particle is not bound by any potential energy, so the potential is zero and this Hamiltonian is the simplest. For one dimension:

and in three dimensions:

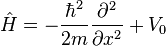

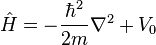

Constant-potential well

For a particle in a region of constant potential V = V0 (no dependence on space or time), in one dimension, the Hamiltonian is:

in three dimensions

This applies to the elementary "particle in a box" problem, and step potentials.

Simple harmonic oscillator

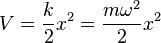

For a simple harmonic oscillator in one dimension, the potential varies with position (but not time), according to:

where the angular frequency, effective spring constant k, and mass m of the oscillator satisfy:

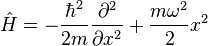

so the Hamiltonian is:

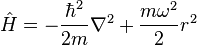

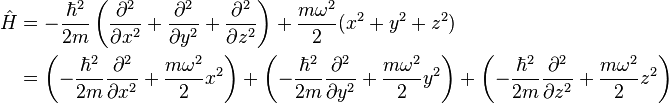

For three dimensions, this becomes

where the three-dimensional position vector r using cartesian coordinates is (x, y, z), its magnitude is

Writing the Hamiltonian out in full shows it is simply the sum of the one-dimensional Hamiltonians in each direction:

Rigid rotor

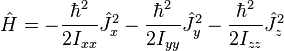

For a rigid rotor – i.e. system of particles which can rotate freely about any axes, not bound in any potential (such as free molecules with negligible vibrational degrees of freedom, say due to double or triple chemical bonds), Hamiltonian is:

where Ixx, Iyy, and Izz are the moment of inertia components (technically the diagonal elements of the moment of inertia tensor), and  ,

,  and

and  are the total angular momentum operators (components), about the x, y, and z axes respectively.

are the total angular momentum operators (components), about the x, y, and z axes respectively.

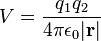

Electrostatic or coulomb potential

The Coulomb potential energy for two point charges q1 and q2 (i.e. charged particles, since particles have no spatial extent), in three dimensions, is (in SI units - rather than Gaussian units which are frequently used in electromagnetism):

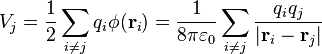

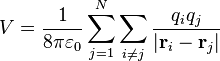

However, this is only the potential for one point charge due to another. If there are many charged particles, each charge has a potential energy due to every other point charge (except itself). For N charges, the potential energy of charge qj due to all other charges is (see also Electrostatic potential energy stored in a configuration of discrete point charges):[3]

where φ(ri) is the electrostatic potential of charge qj at ri. The total potential of the system is then the sum over j:

so the Hamiltonian is:

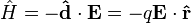

Electric dipole in an electric field

For an electric dipole moment d constituting charges of magnitude q, in a uniform, electrostatic field (time-independent) E, positioned in one place, the potential is:

the dipole moment itself is the operator

Since the particle is stationary, there is no translational kinetic energy of the dipole, so the Hamiltonian of the dipole is just the potential energy:

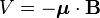

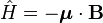

Magnetic dipole in a magnetic field

For a magnetic dipole moment μ in a uniform, magnetostatic field (time-independent) B, positioned in one place, the potential is:

Since the particle is stationary, there is no translational kinetic energy of the dipole, so the Hamiltonian of the dipole is just the potential energy:

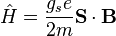

For a Spin-½ particle, the corresponding spin magnetic moment is:[4]

where gs is the spin gyromagnetic ratio (a.k.a. "spin g-factor"), e is the electron charge, S is the spin operator vector, whose components are the Pauli matrices, hence

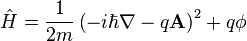

Charged particle in an electromagnetic field

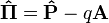

For a charged particle q in an electromagnetic field, described by the scalar potential φ and vector potential A, there are two parts to the Hamiltonian to substitute for.[1] The momentum operator must be replaced by the kinetic momentum operator, which includes a contribution from the A field:

where  is the canonical momentum operator given as the usual momentum operator:

is the canonical momentum operator given as the usual momentum operator:

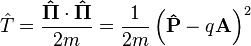

so the corresponding kinetic energy operator is:

and the potential energy, which is due to the φ field:

Casting all of these into the Hamiltonian gives:

Energy eigenket degeneracy, symmetry, and conservation laws

In many systems, two or more energy eigenstates have the same energy. A simple example of this is a free particle, whose energy eigenstates have wavefunctions that are propagating plane waves. The energy of each of these plane waves is inversely proportional to the square of its wavelength. A wave propagating in the x direction is a different state from one propagating in the y direction, but if they have the same wavelength, then their energies will be the same. When this happens, the states are said to be degenerate.

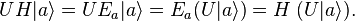

It turns out that degeneracy occurs whenever a nontrivial unitary operator U commutes with the Hamiltonian. To see this, suppose that  is an energy eigenket. Then

is an energy eigenket. Then  is an energy eigenket with the same eigenvalue, since

is an energy eigenket with the same eigenvalue, since

Since U is nontrivial, at least one pair of  and

and  must represent distinct states. Therefore, H has at least one pair of degenerate energy eigenkets. In the case of the free particle, the unitary operator which produces the symmetry is the rotation operator, which rotates the wavefunctions by some angle while otherwise preserving their shape.

must represent distinct states. Therefore, H has at least one pair of degenerate energy eigenkets. In the case of the free particle, the unitary operator which produces the symmetry is the rotation operator, which rotates the wavefunctions by some angle while otherwise preserving their shape.

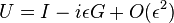

The existence of a symmetry operator implies the existence of a conserved observable. Let G be the Hermitian generator of U:

It is straightforward to show that if U commutes with H, then so does G:

Therefore,

In obtaining this result, we have used the Schrödinger equation, as well as its dual,

Thus, the expected value of the observable G is conserved for any state of the system. In the case of the free particle, the conserved quantity is the angular momentum.

Hamilton's equations

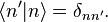

Hamilton's equations in classical Hamiltonian mechanics have a direct analogy in quantum mechanics. Suppose we have a set of basis states  , which need not necessarily be eigenstates of the energy. For simplicity, we assume that they are discrete, and that they are orthonormal, i.e.,

, which need not necessarily be eigenstates of the energy. For simplicity, we assume that they are discrete, and that they are orthonormal, i.e.,

Note that these basis states are assumed to be independent of time. We will assume that the Hamiltonian is also independent of time.

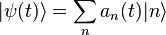

The instantaneous state of the system at time t,  , can be expanded in terms of these basis states:

, can be expanded in terms of these basis states:

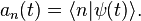

where

The coefficients an(t) are complex variables. We can treat them as coordinates which specify the state of the system, like the position and momentum coordinates which specify a classical system. Like classical coordinates, they are generally not constant in time, and their time dependence gives rise to the time dependence of the system as a whole.

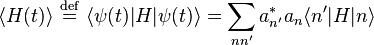

The expectation value of the Hamiltonian of this state, which is also the mean energy, is

where the last step was obtained by expanding  in terms of the basis states.

in terms of the basis states.

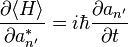

Each of the an(t)'s actually corresponds to two independent degrees of freedom, since the variable has a real part and an imaginary part. We now perform the following trick: instead of using the real and imaginary parts as the independent variables, we use an(t) and its complex conjugate an*(t). With this choice of independent variables, we can calculate the partial derivative

By applying Schrödinger's equation and using the orthonormality of the basis states, this further reduces to

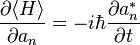

Similarly, one can show that

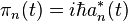

If we define "conjugate momentum" variables πn by

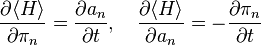

then the above equations become

which is precisely the form of Hamilton's equations, with the  s as the generalized coordinates, the

s as the generalized coordinates, the  s as the conjugate momenta, and

s as the conjugate momenta, and  taking the place of the classical Hamiltonian.

taking the place of the classical Hamiltonian.

See also

- Hamiltonian mechanics

- Operator (physics)

- Bra–ket notation

- Quantum state

- Linear algebra

- Conservation of energy

- Potential theory

- Many-body problem

- Electrostatics

- Electric field

- Magnetic field

- Lieb–Thirring inequality

References

- 1 2 Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei and Particles (2nd Edition), R. Resnick, R. Eisberg, John Wiley & Sons, 1985, ISBN 978-0-471-87373-0

- ↑ Quanta: A handbook of concepts, P.W. Atkins, Oxford University Press, 1974, ISBN 0-19-855493-1

- ↑ Electromagnetism (2nd edition), I.S. Grant, W.R. Phillips, Manchester Physics Series, 2008 ISBN 0-471-92712-0

- ↑ Physics of Atoms and Molecules, B.H. Bransden, C.J.Joachain, Longman, 1983, ISBN 0-582-44401-2

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

![[H, G] = 0 \,](../I/m/9451c7994f3ba73e6a5f85714c812cbc.png)

![\frac{\part}{\part t} \langle\psi(t)|G|\psi(t)\rangle

= \frac{1}{i\hbar} \langle\psi(t)|[G,H]|\psi(t)\rangle

= 0.](../I/m/c19375c997c1b8637683c3db9ed5b6dd.png)