Pyramid of Khafre

| Pyramid of Khafre | |

|---|---|

| |

| Khafre | |

| Coordinates | 29°58′34″N 31°07′51″E / 29.97611°N 31.13083°ECoordinates: 29°58′34″N 31°07′51″E / 29.97611°N 31.13083°E |

| Ancient name | Great is Khafre |

| Constructed | c. 2570 BC (4th dynasty) |

| Type | True pyramid |

| Height |

136.4 metres (448 ft)[1] (Originally: 143.5 m or 471 ft)[1] |

| Base | 215.28 metres (706 ft) |

| Volume | 2,211,096 cubic metres (78,084,118 cu ft) |

| Slope | 53°10' |

The Pyramid of Khafre or of Chephren[1] is the second-tallest and second-largest of the Ancient Egyptian Pyramids of Giza and the tomb of the Fourth-Dynasty pharaoh Khafre (Chefren), who ruled from c. 2558 to 2532 BC.[2]

Size

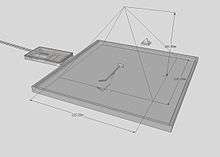

The pyramid has a base length of 215.5 m (706 ft) and rises up to a height of 136.4 metres (448 ft)[1] The pyramid is made of limestone blocks weighing more than 2 tons each. The slope of the pyramid rises at a 53° 10' angle, steeper than its neighbor, the Pyramid of Khufu, which has an angle of 51°50'40". The pyramid sits on bedrock 10 m (33 ft) higher than Khufu’s pyramid, which makes it appear to be taller.

History

The pyramid was likely opened and robbed during the First Intermediate Period. During the Eighteenth Dynasty, the overseer of temple construction took casing stone from it to build a temple in Heliopolis on Ramesses II’s orders.[3] Arab historian Ibn Abd al-Salam recorded that the pyramid was opened in 1372 AD.[4]

On the wall of the burial chamber, there is an Arabic graffito that probably dates from the same time.[5]

It is not known when the casing stones of the pyramid were robbed; however, they were presumably still in place by 1646, when John Greaves, professor of Astronomy at the University of Oxford in his "Pyramidographia," wrote that, while its stones weren't as large or as regularly laid as in Khufu's, the surface was smooth and even free of breaches of inequalities, except on the south.[6]

It was first explored in modern times by Giovanni Belzoni on March 2, 1818, when the original entrance was found on the north side of the pyramid and the burial chamber was visited. Belzoni had hopes of finding an intact burial. However, the chamber was empty except for an open sarcophagus and its broken lid on the floor.[5]

The first complete exploration was conducted by John Perring in 1837. In 1853, Auguste Mariette partially excavated Khafre's valley temple, and, in 1858, while completing its clearance, he managed to discover a diorite statue.[7]

Construction

Like the Great Pyramid, a rock outcropping was used in the core. Due to the slope of the plateau, the northwest corner was cut 10 m (33 ft) out of the rock subsoil and the southeast corner is built up.

The pyramid is built of horizontal courses. The stones used at the bottom are very large, but as the pyramid rises, the stones become smaller, becoming only 50 cm (20 in) thick at the apex. The courses are rough and irregular for the first half of its height but a narrow band of regular masonry is clear in the midsection of the pyramid. At the northwest corner of the pyramid, the bedrock was fashioned into steps.[8] Casing stones cover the top third of the pyramid, but the pyramidion and part of the apex) are missing.

The bottom course of casing stones was made out of pink granite but the remainder of the pyramid was cased in Tura Limestone. Close examination reveals that the corner edges of remaining casing stones are not completely straight, but are staggered by a few millimeters. One theory is that this is due to settling from seismic activity. An alternative theory postulates that the slope on the blocks was cut to shape before being placed due to the limited working space towards the top of the pyramid.[9]

Interior

Two entrances lead to the burial chamber, one that opens 11.54 m (38 ft) up the face of the pyramid and one that opens at the base of the pyramid. These passageways do not align with the centerline of the pyramid, but are offset to the east by 12 m (39 ft). The lower descending passageway is carved completely out of the bedrock, descending, running horizontal, then ascending to join the horizontal passage leading to the burial chamber.

One theory as to why there are two entrances is that the pyramid was intended to be much larger with the northern base shifted 30 m (98 ft) further to the north which would make Khafre’s pyramid much larger than his father’s. This would place the entrance to the lower descending passage within the masonry of the pyramid. While the bedrock is cut away farther from the pyramid on the north side than on the west side, it is not clear that there is enough room on the plateau for the enclosure wall and pyramid terrace. An alternative theory is that, as with many earlier pyramids, plans were changed and the entrance was moved midway through construction.

There is a subsidiary chamber, equal in length to the c.412"-long King's Chamber of the Khufu pyramid,[10] that opens to the west of the lower passage, the purpose of which is uncertain. It may be used to store offerings, store burial equipment, or it may be a serdab chamber. The upper descending passage is clad in granite and descends to join with the horizontal passage to the burial chamber.

The burial chamber was carved out of a pit in the bedrock. The roof is constructed of gabled limestone beams. The chamber is rectangular, 14.15 m by 5 m (46.4 ft x 16 ft), and is oriented east-west. Khafre’s sarcophagus was carved out of a solid block of granite and sunk partially in the floor, in it, Belzoni found bones of an animal, possibly a bull. Another pit in the floor likely contained the canopic chest, its lid would have been one of the pavement slabs.[11]

Pyramid complex

Satellite Pyramid

Along the centerline of the pyramid on the south side was a satellite pyramid, but almost nothing remains other than some core blocks and the outline of the foundation. It contains two descending passages, one of them ending in a dead end with a niche which contained pieces of ritualistic furniture.[12]

Khafre's Temples

The temples of Khafre's complex survive in much better condition than Khufu's, this being specially true to the Valley Temple, which is substantially preserved.[13] To the east of the Pyramid sits the mortuary temple. Though it is now largely in ruins, enough of it survives to understand the plan. It is larger than previous temples and is the first to include all five standard elements of later mortuary temples: an entrance hall, a columned court, five niches for statues of the pharaoh, five storage chambers, and an inner sanctuary. There were over 50 life size statues of Khafre, but these were removed and recycled, possibly by Ramses II. The temple was built of megalithic blocks (the largest is an estimated 400 tonnes[14]).

A causeway runs 494.6 metres (541 yd) to the valley temple, which is very similar to the mortuary temple. It is built of megalithic blocks sheathed in red granite. The square pillars of the T-shaped hallway were made of solid granite, and the floor was paved in alabaster. The exterior was built of huge blocks, some weighing over 100 tonnes.[15] Though devoid of any internal decoration, this temple would have been filled with symbolism: two doors open into a vestibule and a large pillared hall, in which there were sockets in the floor that would have fixed 23 statues of Khafre. These columns have since been plundered. The interior, made of granite of the Valley Temple, is remarkably well preserved. The exterior made of limestone is much more weathered.[16]

The so-called[17] temple of the Sphinx is not attested to any king, but structural similarities to Khafre's mortuary temple point to him as its builder. Opening to a hall with 24 columns, each with its own statue, two sanctuaries and symmetric design, it is possible but unsure if this temple had any symbolism attached to the finished plan.[18]

Sphinx

The sphinx, probably built out of a rock formation used to cut the blocks for the pyramid itself, may have been part of the complex.[19]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Pyramid of Chefren, Giza - SkyscraperPage.com". Skyscraper Source Media Inc. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ Shaw, Ian, "The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt", 2000 p.90

- ↑ Lehner, Mark, "The Complete Pyramids – Solving the Ancient Mysteries", 1997 p.38

- ↑ Dunn, Jimmy. "The Great Pyramid of Khafre at Giza in Egypt". Tour Egypt. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- 1 2 Lehner, 1997 p.49

- ↑ Lehner, 1997 p.44

- ↑ Lehner, 1997 p.55

- ↑ Lehner, 1997 p.45

- ↑ Lehner, 1997 p.122

- ↑ Petrie, The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, 1883:78

- ↑ Lehner, 1997 p.124

- ↑ Lehner, 1997 p.126

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard, "The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt", 200 p.117

- ↑ Siliotti, Alberto, Zahi Hawass, 1997 "Guide to the Pyramids of Egypt" p.62

- ↑ Siliotti, Alberto, Zahi Hawass, 1997 p.63-9

- ↑ Wilkinson, 200 p.117

- ↑ "Giza Sphinx & Temples - Page 1 - Spirit & Stone". Global Education Project. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ Wilkinson, 200 p.118

- ↑ Cohagan, Ryan (12 Dec 2001). "The Pyramid of Khafre". Creighton University. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

Further reading

- Verner, Miroslav, The Pyramids – Their Archaeology and History, Atlantic Books, 2001, ISBN 1-84354-171-8

- Lehner, Mark, The Complete Pyramids – Solving the Ancient Mysteries, Thames & Hudson, 1997, ISBN 0-500-05084-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyramid of Khafra. |

The Giza Archives: http://www.gizapyramids.org/

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|