Barnard's Star

The location of Barnard's Star, ca. 2006 (south is up) | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Ophiuchus |

| Pronunciation | /ˈbɑːrnərd/ |

| Right ascension | 17h 57m 48.49803s[1] |

| Declination | +04° 41′ 36.2072″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 9.511[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | M4.0V[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (U) | 12.497[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (B) | 11.240[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (R) | 8.298[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (I) | 6.741[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (J) | 5.24[4] |

| Apparent magnitude (H) | 4.83[4] |

| Apparent magnitude (K) | 4.524[4] |

| U−B color index | 1.257[2] |

| B−V color index | 1.713[2] |

| Variable type | BY Draconis |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −110.6 ± 0.2[5] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −798.71[1] mas/yr Dec.: 10337.77[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 545.62 ± 0.2[6] mas |

| Distance | 5.978 ± 0.002 ly (1.8328 ± 0.0007 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 13.21[2] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 0.144[7] M☉ |

| Radius | 0.196 ± 0.008[8] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 0.0035[9] L☉ |

| Luminosity (visual, LV) | 0.0004[9] L☉ |

| Temperature | 3,134 ± 102[9] K |

| Metallicity | 10–32% Sun[10] |

| Rotation | 130.4 d[11] |

| Age | About 10[12] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

"Barnard's Runaway Star", "Greyhound of the Skies",[13] BD+04°3561a, GCTP 4098.00, Gl 140-024, Gliese 699, HIP 87937, LFT 1385, LHS 57, LTT 15309, Munich 15040, Proxima Ophiuchi,[14] V2500 Ophiuchi, Velox Barnardi,[15] Vyssotsky 799 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| ARICNS | data |

Barnard's Star /ˈbɑːrnərd/ is a very-low-mass red dwarf about six light-years away from Earth in the constellation of Ophiuchus. It is the fourth-closest known individual star to the Sun (after the three components of the Alpha Centauri system) and the closest star in the Northern Hemisphere.[16] Despite its proximity, at a dim apparent magnitude of about nine, it is not visible with the unaided eye; however, it is much brighter in the infrared than it is in visible light.

The star is named for American astronomer E. E. Barnard. He was not the first to observe the star (it appeared on Harvard University plates in 1888 and 1890), but in 1916 he measured its proper motion as 10.3 arcseconds per year, which remains the largest known proper motion of any star relative to the Solar System.[17]

Barnard's Star is among the most studied red dwarfs because of its proximity and favorable location for observation near the celestial equator.[9] Historically, research on Barnard's Star has focused on measuring its stellar characteristics, its astrometry, and also refining the limits of possible extrasolar planets. Although Barnard's Star is an ancient star, it still experiences star flare events, one being observed in 1998.

The star has also been the subject of some controversy. For a decade, from the early 1960s to the early 1970s, Peter van de Kamp claimed that there were one or more gas giants in orbit around it. Although the presence of small terrestrial planets around Barnard's Star remains a possibility, van de Kamp's specific claims of large gas giants were refuted in the mid-1970s.

Overview

Barnard's Star is a red dwarf of the dim spectral type M4, and it is too faint to see without a telescope. Its apparent magnitude is 9.5. This compares with a magnitude of −1.5 for Sirius – the brightest star in the night sky – and about 6.0 for the faintest objects visible with the naked eye (this magnitude scale is logarithmic, so the magnitude of 9.54 is only about 1/27th of the brightness of the faintest star that can be seen with the naked eye (under good viewing conditions).

At 7–12 billion years of age, Barnard's Star is considerably older than the Sun, which is 4.5 billion years old, and it might be among the oldest stars in the Milky Way galaxy.[12] Barnard's Star has lost a great deal of rotational energy, and the periodic slight changes in its brightness indicate that it rotates once in 130 days[11] (the Sun rotates in 25). Given its age, Barnard's Star was long assumed to be quiescent in terms of stellar activity. However, in 1998, astronomers observed an intense stellar flare, surprisingly showing that Barnard's Star is a flare star.[18] Barnard's Star has the variable star designation V2500 Ophiuchi. In 2003, Barnard's Star presented the first detectable change in the radial velocity of a star caused by its motion. Further variability in the radial velocity of Barnard's Star was attributed to its stellar activity.[19]

The proper motion of Barnard's Star corresponds to a relative lateral speed of 90 km/s. The 10.3 seconds of arc it travels annually amount to a quarter of a degree in a human lifetime, roughly half the angular diameter of the full Moon.[20]

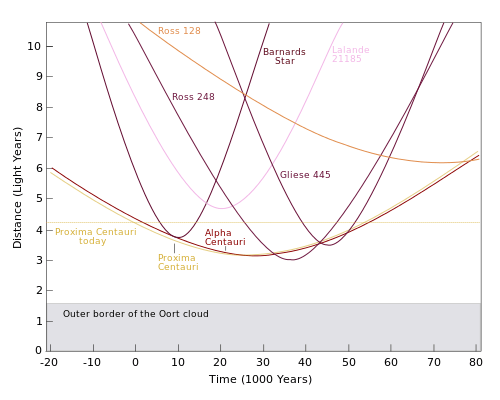

The radial velocity of Barnard's Star towards the Sun is measured from its blue shift to be 110 km/s. Combined with its proper motion, this gives a true velocity relative to the Sun of 143 km/s. Barnard's Star will make its closest approach to the Sun around AD 11,800, when it approaches to within about 3.75 light-years.[7] However, at that time, Barnard's Star will not be the nearest star, since Proxima Centauri will have moved even closer to the Sun.[21] Barnard's Star will still be too dim to be seen with the naked eye at the time of its closest approach, since its apparent magnitude will be about 8.5 then. After that it will gradually recede from the Sun.

Barnard's Star has a mass of about 0.14 solar masses (M☉),[7] and a radius 15% to 20% of that of the Sun.[9][22] Thus, although Barnard's Star has roughly 150 times the mass of Jupiter (MJ), its radius is only 1.5 to 2.0 times larger, due to its much higher density. Its effective temperature is 3,100 kelvins, and it has a visual luminosity of 0.0004 solar luminosities.[9] Barnard's Star is so faint that if it were at the same distance from Earth as the Sun is, it would appear only 100 times brighter than a full moon, comparable to the brightness of the Sun at 80 astronomical units.[23]

Barnard's Star's has 10–32% of the solar metallicity.[10] Metallicity is the proportion of stellar mass made up of elements heavier than helium and helps classify stars relative to the galactic population. Barnard's Star seems to be typical of the old, red dwarf population II stars, yet these are also generally metal-poor halo stars. While sub-solar, Barnard's Star's metallicity is higher than that of a halo star and is in keeping with the low end of the metal-rich disk star range; this, plus its high space motion, have led to the designation "intermediate population II star", between a halo and disk star.[10][19]

Claims of a planetary system

For a decade from 1963 to about 1973, a substantial number of astronomers accepted a claim by Peter van de Kamp that he had detected, by using astrometry, a perturbation in the proper motion of Barnard's Star consistent with its having one or more planets comparable in mass with Jupiter. Van de Kamp had been observing the star from 1938, attempting, with colleagues at the Swarthmore College observatory, to find minuscule variations of one micrometre in its position on photographic plates consistent with orbital perturbations that would indicate a planetary companion; this involved as many as ten people averaging their results in looking at plates, to avoid systemic individual errors.[24] Van de Kamp's initial suggestion was a planet having about 1.6 MJ at a distance of 4.4 AU in a slightly eccentric orbit,[25] and these measurements were apparently refined in a 1969 paper.[26] Later that year, Van de Kamp suggested that there were two planets of 1.1 and 0.8 MJ.[27]

Other astronomers subsequently repeated Van de Kamp's measurements, and two papers in 1973 undermined the claim of a planet or planets. George Gatewood and Heinrich Eichhorn, at a different observatory and using newer plate measuring techniques, failed to verify the planetary companion.[28] Another paper published by John L. Hershey four months earlier, also using the Swarthmore observatory, found that changes in the astrometric field of various stars correlated to the timing of adjustments and modifications that had been carried out on the refractor telescope's objective lens;[29] the claimed planet was attributed to an artifact of maintenance and upgrade work. The affair has been discussed as part of a broader scientific review.[30]

Van de Kamp never acknowledged any error and published a further claim of two planets' existence as late as 1982;[31] he died in 1995. Wulff Heintz, Van de Kamp's successor at Swarthmore and an expert on double stars, questioned his findings and began publishing criticisms from 1976 onwards. The two men were reported to have become estranged from each other because of this.[32]

Refining planetary boundaries

While not completely ruling out the possibility of planets, null results for planetary companions continued throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the latest based on interferometric work with the Hubble Space Telescope in 1999.[33] By refining the values of a star's motion, the mass and orbital boundaries for possible planets are tightened: in this way astronomers are often able to describe what types of planets cannot orbit a given star.

M dwarfs such as Barnard's Star are more easily studied than larger stars in this regard because their lower masses render perturbations more obvious.[35] Gatewood was thus able to show in 1995 that planets with 10 MJ (the lower limit for brown dwarfs) were impossible around Barnard's Star,[30] in a paper which helped refine the negative certainty regarding planetary objects in general.[36] In 1999, work with the Hubble Space Telescope further excluded planetary companions of 0.8 MJ with an orbital period of less than 1,000 days (Jupiter's orbital period is 4,332 days),[33] while Kuerster determined in 2003 that within the habitable zone around Barnard's Star, planets are not possible with an "M sin i" value[37] greater than 7.5 times the mass of the Earth (M⊕), or with a mass greater than 3.1 times the mass of Neptune (much lower than van de Kamp's smallest suggested value).[19]

Even though this research has greatly restricted the possible properties of planets around Barnard's Star, it has not ruled them out completely; terrestrial planets would be difficult to detect. NASA's Space Interferometry Mission, which was to begin searching for extrasolar Earth-like planets, was reported to have chosen Barnard's Star as an early search target.[23] However, this mission was shut down in 2010.[38] ESA's similar Darwin interferometry mission had the same goal, but was stripped of funding in 2007.[39]

Exploration

Project Daedalus

Barnard's Star was studied as part of Project Daedalus. Undertaken between 1973 and 1978, the study suggested that rapid, unmanned travel to another star system was possible with existing or near-future technology.[40] Barnard's Star was chosen as a target partly because it was believed to have planets.[41]

The theoretical model suggested that a nuclear pulse rocket employing nuclear fusion (specifically, electron bombardment of deuterium and helium-3) and accelerating for four years could achieve a velocity of 12% of the speed of light. The star could then be reached in 50 years, within a human lifetime.[41] Along with detailed investigation of the star and any companions, the interstellar medium would be examined and baseline astrometric readings performed.[40]

The initial Project Daedalus model sparked further theoretical research. In 1980, Robert Freitas suggested a more ambitious plan: a self-replicating spacecraft intended to search for and make contact with extraterrestrial life.[42] Built and launched in Jovian orbit, it would reach Barnard's Star in 47 years under parameters similar to those of the original Project Daedalus. Once at the star, it would begin automated self-replication, constructing a factory, initially to manufacture exploratory probes and eventually to create a copy of the original spacecraft after 1,000 years.[42]

1998 flare

In 1998 a stellar flare on Barnard's Star was detected based on changes in the spectral emissions on July 17, 1998, during an unrelated search for variations in the proper motion. Four years passed before the flare was fully analyzed, at which point it was suggested that the flare's temperature was 8000 K, more than twice the normal temperature of the star.[43] Given the essentially random nature of flares, Diane Paulson, one of the authors of that study, noted that "the star would be fantastic for amateurs to observe".[18]

The flare was surprising because intense stellar activity is not expected in stars of such age. Flares are not completely understood, but are believed to be caused by strong magnetic fields, which suppress plasma convection and lead to sudden outbursts: strong magnetic fields occur in rapidly rotating stars, while old stars tend to rotate slowly. For Barnard's Star to undergo an event of such magnitude is thus presumed to be a rarity.[43] Research on the star's periodicity, or changes in stellar activity over a given timescale, also suggest it ought to be quiescent; 1998 research showed weak evidence for periodic variation in the star's brightness, noting only one possible starspot over 130 days.[11]

Stellar activity of this sort has created interest in using Barnard's Star as a proxy to understand similar stars. It is hoped that photometric studies of its X-ray and UV emissions will shed light on the large population of old M dwarfs in the galaxy. Such research has astrobiological implications: given that the habitable zones of M dwarfs are close to the star, any planets would be strongly influenced by solar flares, winds, and plasma ejection events.[12]

Environment

Barnard's Star shares much the same neighborhood as the Sun. The neighbors of Barnard's Star are generally of red dwarf size, the smallest and most common star type. Its closest neighbor is currently the red dwarf Ross 154, at 1.66 parsecs (5.41 light years) distance. The Sun and Alpha Centauri are, respectively, the next closest systems.[23] From Barnard's Star, the Sun would appear on the diametrically opposite side of the sky at coordinates RA=5h 57m 48.5s, Dec=−04° 41′ 36″, in the eastern part of the constellation Monoceros. The absolute magnitude of the Sun is 4.83, and at a distance of 1.834 parsecs, it would be a first-magnitude star, as Pollux is from the Earth.[44]

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Koen, C.; Kilkenny, D.; Van Wyk, F.; Marang, F. (2010). "UBV(RI)C JHK observations of Hipparcos-selected nearby stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 403 (4): 1949. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.403.1949K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.16182.x.

- ↑ Gizis, John E. (1997). "M-Subdwarfs: Spectroscopic Classification and the Metallicity Scale". Astronomical Journal v.113 113: 806. arXiv:astro-ph/9611222. Bibcode:1997AJ....113..806G. doi:10.1086/118302.

- 1 2 3 Cutri, R. M.; Skrutskie, M. F.; Van Dyk, S.; Beichman, C. A.; Carpenter, J. M.; Chester, T.; Cambresy, L.; Evans, T.; Fowler, J.; Gizis, J.; Howard, E.; Huchra, J.; Jarrett, T.; Kopan, E. L.; Kirkpatrick, J. D.; Light, R. M.; Marsh, K. A.; McCallon, H.; Schneider, S.; Stiening, R.; Sykes, M.; Weinberg, M.; Wheaton, W. A.; Wheelock, S.; Zacarias, N. (2003). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: 2MASS All-Sky Catalog of Point Sources (Cutri+ 2003)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: II/246. Originally published in: 2003yCat.2246....0C 2246: 0. Bibcode:2003yCat.2246....0C.

- ↑ Bobylev, Vadim V. (March 2010). "Searching for Stars Closely Encountering with the Solar System". Astronomy Letters 36 (3): 220–226. arXiv:1003.2160. Bibcode:2010AstL...36..220B. doi:10.1134/S1063773710030060.

- ↑ This parallax measurement and the subsequent distance calculation are based on the averages of the distance measurements provided below, taking into account the accuracy of each measurement. SIMBAD suggests less precise parallax by van Leeuwen (2007) of 548.31 ± 1.51 mas and thus a slightly lesser distance from the Sun of 5.95 ly (1.82 pc).

- 1 2 3 Bobylev, V. V. (March 2010), "Searching for stars closely encountering with the solar system", Astronomy Letters 36 (3): 220–226, arXiv:1003.2160, Bibcode:2010AstL...36..220B, doi:10.1134/S1063773710030060

- ↑ Demory, B.-O.; et al. (October 2009), "Mass-radius relation of low and very low-mass stars revisited with the VLTI", Astronomy and Astrophysics 505 (1): 205–215, arXiv:0906.0602, Bibcode:2009A&A...505..205D, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200911976

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dawson, P. C.; De Robertis, M. M. (2004). "Barnard's Star and the M Dwarf Temperature Scale". The Astronomical Journal 127 (5): 2909. Bibcode:2004AJ....127.2909D. doi:10.1086/383289.

- 1 2 3 Gizis, John E. (February 1997). "M-Subdwarfs: Spectroscopic Classification and the Metallicity Scale". The Astronomical Journal 113 (2): 820. arXiv:astro-ph/9611222. Bibcode:1997AJ....113..806G. doi:10.1086/118302.

- 1 2 3 Benedict, G. Fritz; McArthur, Barbara; Nelan, E.; Story, D.; Whipple, A. L.; Shelus, P. J.; Jefferys, W. H.; Hemenway, P. D.; Franz, Otto G.; Wasserman, L. H.; Duncombe, R. L.; Van Altena, W.; Fredrick, L. W. (1998). "Photometry of Proxima Centauri and Barnard's star using Hubble Space Telescope fine guidance senso 3". The Astronomical Journal 116 (1): 429. arXiv:astro-ph/9806276. Bibcode:1998AJ....116..429B. doi:10.1086/300420.

- 1 2 3 Riedel, A. R.; Guinan, E. F.; DeWarf, L. E.; Engle, S. G.; McCook, G. P. (May 2005). "Barnard's Star as a Proxy for Old Disk dM Stars: Magnetic Activity, Light Variations, XUV Irradiances, and Planetary Habitable Zones". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 37: 442. Bibcode:2005AAS...206.0904R.

- ↑ "Barnard's Star and its Perturbations". Spaceflight (British Interplanetary Society). 11–12: 170. 1969.

- ↑ Perepelkin, E. (April 1927). "Einweißer Stern mit bedeutender absoluter Größe". Astronomische Nachrichten (in German) 230 (4): 77. Bibcode:1927AN....230...77P. doi:10.1002/asna.19272300406.

- ↑ Rukl, Antonin (1999). "Constellation Guidebook". Sterling Publishing: 158. ISBN 0-8069-3979-6.

- ↑ http://shiva.uwp.edu/p120/astro_survey.html

- ↑ Barnard, E. E. (1916). "A small star with large proper motion". Astronomical Journal 29 (695): 181. Bibcode:1916AJ.....29..181B. doi:10.1086/104156.

- 1 2 Croswell, Ken (November 2005). "A Flare for Barnard's Star". Astronomy Magazine. Kalmbach Publishing Co. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- 1 2 3 Kürster, M.; Endl, M.; Rouesnel, F.; Els, S.; Kaufer, A.; Brillant, S.; Hatzes, A. P.; Saar, S. H.; Cochran, W. D. (2003). "The low-level radial velocity variability in Barnard's Star". Astronomy and Astrophysics 403 (6): 1077. arXiv:astro-ph/0303528. Bibcode:2003A&A...403.1077K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030396.

- ↑ Kaler, James B. (November 2005). "Barnard's Star (V2500 Ophiuchi)". Stars. James B. Kaler. Archived from the original on 5 September 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2006.

- ↑ Matthews, R. A. J.; Weissman, P. R.; Preston, R. A.; Jones, D. L.; Lestrade, J.-F.; Latham, D. W.; Stefanik, R. P.; Paredes, J. M. (1994). "The Close Approach of Stars in the Solar Neighborhood". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 35: 1–9. Bibcode:1994QJRAS..35....1M.

- ↑ Ochsenbein, F. (March 1982). "A list of stars with large expected angular diameters". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series 47: 523–531. Bibcode:1982A&AS...47..523O.

- 1 2 3 "Barnard's Star". Sol Station. Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved August 10, 2006.

- ↑ "The Barnard's Star Blunder". Astrobiology Magazine. July 2005. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ Van de Kamp, Peter. (1963). "Astrometric study of Barnard's star from plates taken with the 24-inch Sproul refractor". Astronomical Journal 68 (7): 515. Bibcode:1963AJ.....68..515V. doi:10.1086/109001. Archived

- ↑ Van de Kamp, Peter. (1969). "Parallax, proper motion acceleration, and orbital motion of Barnard's Star". Astronomical Journal 74 (2): 238. Bibcode:1969AJ.....74..238V. doi:10.1086/110799.

- ↑ Van de Kamp, Peter. (1969). "Alternate dynamical analysis of Barnard's star". Astronomical Journal 74 (8): 757. Bibcode:1969AJ.....74..757V. doi:10.1086/110852.

- ↑ Gatewood, George, and Eichhorn, H. (1973). "An unsuccessful search for a planetary companion of Barnard's star (BD +4 3561)". Astronomical Journal 78 (10): 769. Bibcode:1973AJ.....78..769G. doi:10.1086/111480.

- ↑ John L. Hershey (1973). "Astrometric analysis of the field of AC +65 6955 from plates taken with the Sproul 24-inch refractor". Astronomical Journal 78 (6): 421. Bibcode:1973AJ.....78..421H. doi:10.1086/111436.

- 1 2 Bell, George H. (April 2001). "The Search for the Extrasolar Planets: A Brief History of the Search, the Findings and the Future Implications, Section 2". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved August 10, 2006. Full description of the Van de Kamp planet controversy. Archived

- ↑ Van de Kamp, Peter. (1982). "The planetary system of Barnard's star". Vistas in Astronomy 26 (2): 141. Bibcode:1982VA.....26..141V. doi:10.1016/0083-6656(82)90004-6.

- ↑ Kent, Bill (2001). "Barnard's Wobble" (PDF). Bulletin. Swarthmore College. Retrieved June 2, 2010. Archived

- 1 2 Benedict, G. Fritz; McArthur, Barbara; Chappell, D. W.; Nelan, E.; Jefferys, W. H.; Van Altena, W.; Lee, J.; Cornell, D.; Shelus, P. J.; Hemenway, P. D.; Franz, Otto G.; Wasserman, L. H.; Duncombe, R. L.; Story, D.; Whipple, A. L.; Fredrick, L. W. (1999). "Interferometric Astrometry of Proxima Centauri and Barnard's Star Using HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE Fine Guidance Sensor 3: Detection Limits for Substellar Companions". The Astronomical Journal 118 (2): 1086–1100. arXiv:astro-ph/9905318. Bibcode:1999AJ....118.1086B. doi:10.1086/300975.

- ↑ Clavin, Whitney; Harrington, J.D. (25 April 2014). "NASA's Spitzer and WISE Telescopes Find Close, Cold Neighbor of Sun". NASA. Archived from the original on 2014-04-25. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ↑ Endl, Michael; Cochran, William D.; Tull, Robert G.; MacQueen, Phillip J. (2003). "A Dedicated M Dwarf Planet Search Using the Hobby-Eberly Telescope". The Astronomical Journal 126 (12): 3099–107. arXiv:astro-ph/0308477. Bibcode:2003AJ....126.3099E. doi:10.1086/379137.

- ↑ George D. Gatewood (1995). "A study of the astrometric motion of Barnard's star". Journal Astrophysics and Space Science 223 (1): 91–98. Bibcode:1995Ap&SS.223...91G. doi:10.1007/BF00989158.

- ↑ "M sin i" means the mass of the planet times the sine of the angle of inclination of its orbit, and hence provides the minimum mass for the planet.

- ↑ Marr, James (8 November 2010). "Updates from the Project Manager". NASA. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Darwin factsheet: Finding Earth-like planets". European Space Agency. October 23, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- 1 2 Bond, A., and Martin, A.R. (1976). "Project Daedalus — The mission profile". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 29 (2): 101. Bibcode:1976JBIS...29..101B. Retrieved August 15, 2006.

- 1 2 Darling, David (July 2005). "Daedalus, Project". The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Archived from the original on 31 August 2006. Retrieved August 10, 2006.

- 1 2 Freitas, Robert A., Jr. (July 1980). "A Self-Reproducing Interstellar Probe". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 33: 251–264. Bibcode:1980JBIS...33..251F. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- 1 2 Paulson, Diane B.; Allred, Joel C.; Anderson, Ryan B.; Hawley, Suzanne L.; Cochran, William D.; Yelda, Sylvana (2006). "Optical Spectroscopy of a Flare on Barnard's Star". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 118 (1): 227. arXiv:astro-ph/0511281. Bibcode:2006PASP..118..227P. doi:10.1086/499497.

- ↑ The Sun's apparent magnitude from Barnard's Star, assuming negligible extinction:

.

.

Notes

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barnard's Star. |

- "Barnard's Star". SolStation.

- Darling, David. "Barnard's Star". The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight.

- Schmidling, Jack. "Barnard's Star". Jack Schmidling Productions, Inc. Amateur work showing Barnard's Star movement over time.

- Johnson, Rick. "Barnard's Star". Animated image with frames approx. one year apart, beginning in 2007, showing the movement of Barnard's Star.

Coordinates: ![]() 17h 57m 48.5s, +04° 41′ 36″

17h 57m 48.5s, +04° 41′ 36″

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||