Proto-Indo-Europeans

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Archaeology Steppe Europe Steppe Europe South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies

|

|

Religion and mythology |

The Proto-Indo-Europeans were the speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE), a reconstructed prehistoric language of Eurasia.

Knowledge of them comes chiefly from the linguistic reconstruction, along with material evidence from archaeology and archaeogenetics. According to some archaeologists, PIE speakers cannot be assumed to have been a single, identifiable people or tribe, but were a group of loosely related populations ancestral to the later, still partially prehistoric, Bronze Age Indo-Europeans. This view is held especially by those archaeologists who believed it to be an original homeland of vast extent and immense time depth. However, this view is not shared by linguists, as proto-languages, like all languages before modern transport and communication, occupied small geographical areas over a limited time span, and were spoken by a set of close-knit communities—a tribe in the broad sense.

The Proto-Indo-Europeans likely lived during the late Neolithic, or roughly the 4th millennium BC. Mainstream scholarship places them in the forest-steppe zone immediately to the north of the western end of the Pontic-Caspian steppe in Eastern Europe. Some archaeologists would extend the time depth of PIE to the middle Neolithic (5500 to 4500 BCE) or even the early Neolithic (7500 to 5500 BC), and suggest alternative location hypotheses.

By the early second millennium BC, offshoots of the Proto-Indo-Europeans had reached far and wide across Eurasia, including Anatolia (Hittites), the Aegean (Mycenaean Greece), Western Europe (Corded Ware culture), the edges of Central Asia (Yamna culture), and southern Siberia (Afanasevo culture).[1]

The Proto-Indo-Europeans were in the past referred to by many scholars as Aryans.

Culture

The following basic traits of the Proto-Indo-Europeans and their environment are widely agreed upon but still hypothetical due to their reconstructed nature:

- Pastoralism, including domesticated cattle, horses, and dogs[2]

- agriculture and cereal cultivation, including technology commonly ascribed to late-Neolithic farming communities, e.g., the plow[3]

- a climate with winter snow[4]

- transportation by or across water[2]

- the solid wheel,[2] used for wagons, but not yet chariots with spoked wheels[5]

- worship of a sky god,[3] *dyeus ph2tēr (lit. "sky father"; > Ancient Greek Ζεύς (πατήρ) / Zeus (patēr); *dieu-ph2tēr > Latin Jupiter; Illyrian Deipaturos)[6][7]

- oral heroic poetry or song lyrics that used stock phrases such as imperishable fame[2]

- a patrilineal kinship-system based on relationships between men[2]

The Proto-Indo-Europeans had a patrilineal society, relying largely on agriculture, but partly on animal husbandry, notably of cattle and sheep. They had domesticated horses – *eḱwos (cf. Latin equus). The cow (*gwous) played a central role, in religion and mythology as well as in daily life. A man's wealth would have been measured by the number of his animals (small livestock), *peḱu (cf. English fee, Latin pecunia).

They practiced a polytheistic religion centered on sacrificial rites, probably administered by a priestly caste. Burials in barrows or tomb chambers apply to the Kurgan culture, in accordance with the original version of the Kurgan hypothesis, but not to the previous Sredny Stog culture, which is also generally associated with PIE. Important leaders would have been buried with their belongings in kurgans, and possibly also with members of their households or wives (human sacrifice, suttee).

Many Indo-European societies know a threefold division of priests, a warrior class, and a class of peasants or husbandmen. Georges Dumézil has suggested such a division for Proto-Indo-European society.

If there was a separate class of warriors, it probably consisted of single young men. They would have followed a separate warrior code unacceptable in the society outside their peer-group. Traces of initiation rites in several Indo-European societies suggest that this group identified itself with wolves or dogs (see also Berserker, werewolf).

As for technology, reconstruction indicates a culture of the late Neolithic bordering on the early Bronze Age, with tools and weapons very likely composed of "natural bronze" (i.e., made from copper ore naturally rich in silicon or arsenic). Silver and gold were known, but not silver smelting (as PIE has no word for lead, a by-product of silver smelting), thus suggesting that silver was imported. Sheep were kept for wool, and textiles were woven. The wheel was known, certainly for ox-drawn wagons.

History of research

Researchers have made many attempts to identify particular prehistoric cultures with the Proto-Indo-European-speaking peoples, but all such theories remain speculative. Any attempt to identify an actual people with an unattested language depends on a sound reconstruction of that language that allows identification of cultural concepts and environmental factors associated with particular cultures (such as the use of metals, agriculture vs. pastoralism, geographically distinctive plants and animals, etc.).

The scholars of the 19th century who first tackled the question of the Indo-Europeans' original homeland (also called Urheimat, from German), had essentially only linguistic evidence. They attempted a rough localization by reconstructing the names of plants and animals (importantly the beech and the salmon) as well as the culture and technology (a Bronze Age culture centered on animal husbandry and having domesticated the horse). The scholarly opinions became basically divided between a European hypothesis, positing migration from Europe to Asia, and an Asian hypothesis, holding that the migration took place in the opposite direction.

In the early 20th century, the question became associated with the expansion of a supposed "Aryan race".[8] The question remains contentious within some flavours of ethnic nationalism (see also Indigenous Aryans).

A series of major advances occurred in the 1970s due to the convergence of several factors. First, the radiocarbon dating method (invented in 1949) had become sufficiently inexpensive to be applied on a mass scale. Through dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), pre-historians could calibrate radiocarbon dates to a much higher degree of accuracy. And finally, before the 1970s, parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia had been off limits to Western scholars, while non-Western archaeologists did not have access to publication in Western peer-reviewed journals. The pioneering work of Marija Gimbutas, assisted by Colin Renfrew, at least partly addressed this problem by organizing expeditions and arranging for more academic collaboration between Western and non-Western scholars.

The Kurgan hypothesis, as of 2014 the most widely held theory, depends on linguistic and archaeological evidence, but is not universally accepted.[9][10] It suggests PIE origin in the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the Chalcolithic. A minority of scholars prefers the Anatolian hypothesis, suggesting an origin in Anatolia during the Neolithic. Other theories (Armenian hypothesis, Out of India theory, Paleolithic Continuity Theory, Balkan hypothesis) have only marginal scholarly support.

In regard to terminology, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the term Aryan was used to refer to the Proto-Indo-Europeans and their descendants. Though the term more properly applies to the Indo-European branch that settled Persia and India it came to be used for the broader ethnic family. By the early twentieth century this term had come to be widely used in a racist context referring to a hypothesized white master race, culminating with the pogroms of the Nazis in Europe. Subsequently the term Aryan as a general term for Indo-Europeans has been largely abandoned by scholars (though the term Indo-Aryan is still used to refer to the branch that settled in India).[11]

Urheimat hypotheses

Researchers have put forward a great variety of proposed locations for the first speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Few of these hypotheses have survived scrutiny by academic specialists in Indo-European studies sufficiently well to be included in modern academic debate.[13] The three remaining contenders are summarized here.

In 1956 Marija Gimbutas (1921-1994) first proposed the Kurgan hypothesis. The name originates from the kurgans (burial mounds) of the Eurasian steppes. The hypothesis suggests that the Indo-Europeans, a nomadic tribe of the Pontic-Caspian steppe (now Eastern Ukraine and Southern Russia), expanded in several waves during the 3rd millennium BC. Their expansion coincided with the taming of the horse. Leaving archaeological signs of their presence (see battle-axe people), they subjugated the peaceful European neolithic farmers of Gimbutas' Old Europe. As Gimbutas' beliefs evolved, she put increasing emphasis on the patriarchal, patrilinear nature of the invading culture, sharply contrasting it with the supposedly egalitarian, if not matrilinear culture of the invaded, to a point of formulating essentially feminist archaeology. A modified form of this theory by JP Mallory, dating the migrations earlier (to around 3500 BC) and putting less insistence on their violent or quasi-military nature, remains the most widely held view of the Proto-Indo-European expansion.

The Anatolian hypothesis proposes that the Indo-European languages spread peacefully into Europe from Asia Minor from around 7000 BCE with the advance of farming (wave of advance). The leading propagator of the theory is Colin Renfrew. The culture of the Indo-Europeans as inferred by linguistic reconstruction raises difficulties for this theory, since early neolithic cultures had neither the horse, nor the wheel, nor metal, terms for all of which are securely reconstructed for Proto-Indo-European. Renfrew dismisses this argument, comparing such reconstructions to a theory that the presence of the word "café" in all modern Romance languages implies that the ancient Romans had cafés too. The linguistic counter-argument to this might state that whereas there can be no clear Proto-Romance reconstruction of the word "café" according to historical linguistic methodology, words such as "wheel" in the Indo-European languages clearly point to an archaic form of the protolanguage. Another argument against Renfrew is the fact that ancient Anatolia is known to have been inhabited by non-Indo-European Caucasian-speaking peoples, namely the Hattians, the Georgian Chalybes, and the Hurrians.

Using stochastic models of word evolution to study the presence or absence of different words across Indo-European languages, Gray and Atkinson suggested that the origin of Indo-European goes back about 8500 years, the first split being that of Hittite from the rest, supporting the Indo-Hittite hypothesis. They attempt to avoid one problem associated with traditional glottochronology – that of linguistic borrowing. However, they inherit the main problems of glottochronology, including the lack of proof that languages have a steady rate of lexical replacement. Their calculations rely entirely on Swadesh lists, and while the results are quite robust for well-attested branches, their crucial calculation of the age of Hittite rests on a 200–word Swadesh list of a single language.[14] A more recent paper analyzing 24 mostly ancient languages, including three Anatolian languages, produced the same time-estimates and an early Anatolian split.[15] These claims remain controversial, however, and most traditional linguists consider these methods too inaccurate to prove the Anatolian hypothesis.[16]

The Armenian hypothesis, based on the Glottalic theory, suggests that the Proto-Indo-European language was spoken during the 4th millennium BCE in the Armenian Highland. It is an Indo-Hittite model and does not include the Anatolian languages in its scenario. The phonological peculiarities of PIE proposed in the Glottalic theory would be best preserved in the Armenian language and the Germanic languages, the former assuming the role of the dialect which remained in situ, implied to be particularly archaic in spite of its late attestation. Proto-Greek would be practically equivalent to Mycenean Greek and would date to the 17th century BCE, closely associating Greek migration to Greece with the Indo-Aryan migration to India at about the same time (viz., Indo-European expansion at the transition to the Late Bronze Age, including the possibility of Indo-European Kassites). The Armenian hypothesis argues for the latest possible date of Proto-Indo-European (sans Anatolian), a full millennium later than the mainstream Kurgan hypothesis. In this, it figures as an opposite to the Anatolian hypothesis, in spite of the geographical proximity of the respective Urheimaten suggested, diverging from the time-frame suggested there by a full three millennia.[17]

Genetics

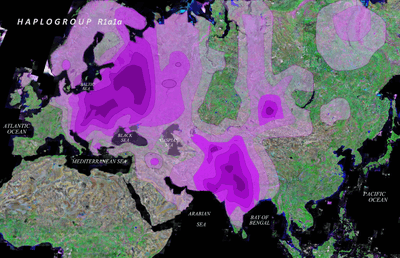

The rise of archaeogenetic evidence which uses genetic analysis to trace migration patterns also added new elements to the origins puzzle. In terms of genetics, the subclade R1a1a (R-M17 or R-M198) is the most commonly associated with Indo-European speakers, although the subclade R1b1a (P-297) has also been linked to the Centum branch of Indo-European.. The subclade's parent Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup R1a1 is thought to have originated in either the Eurasian Steppe (north of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea) or the Indus Valley.[18] The mutations that characterize haplogroup R1a occurred ~10,000 years BP. Its defining mutation (M17) occurred about 10,000 to 14,000 years ago. Ornella Semino et al. propose a postglacial (Holocene) spread of the R1a1 haplogroup from north of the Black Sea during the time of the Late Glacial Maximum, which was subsequently magnified by the expansion of the Kurgan culture into Europe and eastward.[19] Data so far collected indicate that there are two widely separated areas of high frequency, one in Eastern Europe, around Poland and the Russian core, and the other in South Asia, around North India. The historical and prehistoric possible reasons for this are the subject of on-going discussion and attention amongst population geneticists and genetic genealogists, and are considered to be of potential interest to linguists and archaeologists also.

Out of 10 human male remains assigned to the Andronovo horizon from the Krasnoyarsk region, nine possessed the R1a Y-chromosome haplogroup and one C-M130 haplogroup (xC3). mtDNA haplogroups of nine individuals assigned to the same Andronovo horizon and region were as follows: U4 (two individuals), U2e, U5a1, Z, T1, T4, H, and K2b. Furthermore, 90% of the Bronze Age period mtDNA haplogroups were of west Eurasian origin and the study determined that at least 60% of the individuals overall (out of the 26 Bronze and Iron Age human remains' samples of the study that could be tested) had light hair and blue or green eyes.[20]

A 2004 study also established that during the Bronze Age/Iron Age period, the majority of the population of Kazakhstan (part of the Andronovo culture during Bronze Age), was of west Eurasian origin (with mtDNA haplogroups such as U, H, HV, T, I and W), and that prior to the 13th–7th centuries BCE, all samples from Kazakhstan belonged to European lineages.[21]

Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza and Alberto Piazza argue that Renfrew and Gimbutas reinforce rather than contradict each other. Cavalli-Sforza (2000) states that "It is clear that, genetically speaking, peoples of the Kurgan steppe descended at least in part from people of the Middle Eastern Neolithic who immigrated there from Turkey." Piazza & Cavalli-Sforza (2006) state that:

if the expansions began at 9,500 years ago from Anatolia and at 6,000 years ago from the Yamnaya culture region, then a 3,500-year period elapsed during their migration to the Volga-Don region from Anatolia, probably through the Balkans. There a completely new, mostly pastoral culture developed under the stimulus of an environment unfavourable to standard agriculture, but offering new attractive possibilities. Our hypothesis is, therefore, that Indo-European languages derived from a secondary expansion from the Yamnaya culture region after the Neolithic farmers, possibly coming from Anatolia and settled there, developing pastoral nomadism.

A study was published in 2015 of DNA from 94 skeletons from Europe and Russia aged between 3,000 and 8,000 years old.[22] Researchers concluded that about 4,500 years ago there was a major influx into Europe of Yamna culture people originating from the Pontic-Caspian steppe north of the Black Sea and that the DNA of copper-age Europeans matched that of the Yamnaya.[23][24]

The four Corded Ware people could trace an astonishing three-quarters of their ancestry to the Yamnaya, according to the paper. That suggests a massive migration of Yamnaya people from their steppe homeland into eastern Europe about 4500 years ago when the Corded Ware culture began, perhaps carrying an early form of Indo-European language.

Spencer Wells suggests in a (2001) study that the origin, distribution and age of the R1a1 haplotype points to an ancient migration, possibly corresponding to the spread by the Kurgan people in their expansion across the Eurasian steppe around 3000 BCE. About his old teacher Cavalli-Sforza's proposal, Wells (2002) states that "there is nothing to contradict this model, although the genetic patterns do not provide clear support either", and instead argues that the evidence is much stronger for Gimbutas' model:

While we see substantial genetic and archaeological evidence for an Indo-European migration originating in the southern Russian steppes, there is little evidence for a similarly massive Indo-European migration from the Middle East to Europe. One possibility is that, as a much earlier migration (8,000 years old, as opposed to 4,000), the genetic signals carried by Indo-European-speaking farmers may simply have dispersed over the years. There is clearly some genetic evidence for migration from the Middle East, as Cavalli-Sforza and his colleagues showed, but the signal is not strong enough for us to trace the distribution of Neolithic languages throughout the entirety of Indo-European-speaking Europe.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 4 and 6 (Afanasevo), 13 and 16 (Anatolia), 243 (Greece), 127–128 (Corded Ware), and 653 (Yamna). ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Calvert Watkins. "Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. 2000". Archived from the original on 2009-03-01. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- 1 2 The Oxford Companion to Archaeology – Edited by Brian M. Fagan, Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-19-507618-4, p 347 – J.P. Mallory

- ↑ "The Indo-Europeans knew snow in their homeland; the word sneigwh- is nearly ubiquitous." The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. 2000 at the Wayback Machine (archived March 1, 2009)

- ↑ The Oxford introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world – J. P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams, Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-19-929668-5, p249

- ↑ "Yet, for the Indo-European-speaking society, we can reconstruct with certainty the word for “god,” *deiw-os, and the two-word name of the chief deity of the pantheon, *dyeu-pəter- (Latin Iūpiter, Greek Zeus patēr, Sanskrit Dyauṣ pitar, and Luvian Tatis Tiwaz)." The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. 2000 at the Wayback Machine (archived March 1, 2009)

- ↑ Barfield, Owen (1967). "History in English Words". ISBN 9780940262119.

- ↑ Mish, Frederic C., Editor in Chief Webster's Tenth New Collegiate Dictionary Springfield, Massachusetts, U.S.A.:1994--Merriam-Webster See original definition (definition #1) of "Aryan" in English--Page 66

- ↑ Underhill, Peter A.; et al. (2010). "Separating the post-Glacial coancestry of European and Asian Y chromosomes within haplogroup R1a". European Journal of Human Genetics 18 (4): 479–84. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.194. PMC 2987245. PMID 19888303.

- ↑ Sahoo, Sanghamitra; et al. (January 2006). "A prehistory of Indian Y chromosomes: Evaluating demic diffusion scenarios". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (4): 843–48. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507714103. PMC 1347984. PMID 16415161.

- ↑ Pereltsvaig, Asya; Lewis, Martin W. (2015). "1". The Indo-European Controversy: Facts and Fallacies in Historical Linguistics. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Christopher I. Beckwith (2009), Empires of the Silk Road, Oxford University Press, p.30

- ↑ JP Mallory, In Search of the Indo-Europeans, 2nd edn (1991)

- ↑ Gray and Atkinson, Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin, Nature vol. 426 (2003), pp. 435–9.

- ↑ Atkinson, et al., From Words to Dates: Water into wine, mathemagic or phylogenetic inference? Transactions of the Philological Society, vol. 103, no.2 (2005), pp. 193–219.

- ↑ Häkkinen, Jaakko 2012: Problems in the method and interpretations of the computational phylogenetics based on linguistic data - An example of wishful thinking: Bouckaert et al. 2012. http://www.mv.helsinki.fi/home/jphakkin/Problems_of_phylogenetics.pdf

- ↑ T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov, The Early History of Indo-European Languages, Scientific American (March 1990); I.M. Diakonoff, The Prehistory of the Armenian People (1984).

- ↑ "ISOGG 2010 Y-DNA Haplogroup R". Isogg.org. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ↑ http://hpgl.stanford.edu/publications/Science_2000_v290_p1155.pdf

- ↑ Keyser, C.; Bouakaze, C.; Crubézy, E.; Nikolaev, V. G.; Montagnon, D.; Reis, T.; Ludes, B. (2009). "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people". Human Genetics 126 (3): 395–410. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0683-0. PMID 19449030.

- ↑ C. Lalueza-Fox et al. 2004. Unravelling migrations in the steppe: mitochondrial DNA sequences from ancient central Asians

- ↑ Indo-European languages tied to herders, Science 20 February 2015: Vol. 347 no. 6224 pp. 814-815 doi:10.1126/science.347.6224.814

- ↑ Callaway, E. (2015). "European languages linked to migration from the east". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.16919.

- ↑ Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Llamas, B.; Brandt, G.; Nordenfelt, S.; Harney, E.; Stewardson, K.; Fu, Q.; Mittnik, A.; Bánffy, E.; Economou, C.; Francken, M.; Friederich, S.; Pena, R. G.; Hallgren, F.; Khartanovich, V.; Khokhlov, A.; Kunst, M.; Kuznetsov, P.; Meller, H.; Mochalov, O.; Moiseyev, V.; Nicklisch, N.; Pichler, S. L.; Risch, R.; Rojo Guerra, M. A.; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe" (PDF). Nature 522: 207–211. doi:10.1038/nature14317.

Further reading

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05887-3.

- Atkinson, Q. D., Nicholls, G., Welch, D. and Gray, R. D. (2005). From Words to Dates: Water into wine, mathemagic or phylogenetic inference? Transactions of the Philological Society, 103(2), 193–219.

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca (2000). "Genes, Peoples, and Languages". New York: North Point Press..

- Gray, Russell D.; Atkinson, Quentin D. (2003). "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin" (PDF). Nature 426 (6965): 435–439. doi:10.1038/nature02029. PMID 14647380..

- Holm, Hans J. (2007): The new Arboretum of Indo-European "Trees". Can new Algorithms Reveal the Phylogeny and even Prehistory of IE? In: Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 14–2:167–214.

- Mallory, J.P. (1989). "In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth". London: Thames & Hudson..

- Piazza, Alberto; Cavalli Sforza, Luigi (12 – 15 April 2006). "Diffusion of Genes and Languages in Human Evolution". In Cangelosi, Angelo; Smith, Andrew D M; Smith, Kenny. The Evolution of Language: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on the Evolution of Language (EVOLANG6). Rome: World Scientific. pp. 255–266. Retrieved 2007-08-08. Check date values in:

|date=(help). - Renfrew, Colin (1987). Archaeology & Language. The Puzzle of the Indo-European Origins. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-02495-7

- Sykes, Brian. The seven daughters of Eve (London, Corgi Books 2001)

- Watkins, Calvert. (1995) How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wells, Spencer (2002). "The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey". Princeton University Press..

External links

| Look up Appendix:List of Proto-Indo-European roots in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up Appendix:Proto-Indo-European roots in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Indo-European Roots Index at the Wayback Machine (archived 22 January 2009) from The American Heritage Dictionary

- Kurgan culture