Southern Nigeria Protectorate

| Southern Nigeria Protectorate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Protectorate of the British Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem God Save the Queen | ||||||||||||||||||||||

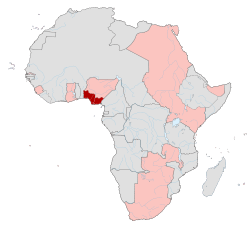

Southern Nigeria (red) British possessions in Africa (pink) 1913 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Lagos (administrative centre from 1906) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | English (official) Yoruba, Igbo, Ibibio, Tiv, Edo, Ijaw languages widely spoken | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity, Odinani, Yoruba religion, Islam, African traditional religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1900–1901 | Victoria | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1901–1910 | Edward VII | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1910–1914 | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||

| High Commissioner | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1900–1904 | Ralph Moor | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1904–1906 | Walter Egerton | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1906–1912 | Walter Egerton | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1912–1914 | Frederick Lugard | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Established | 1 January 1900 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1 January 1914 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1913 | 206,888 km² (79,880 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1911 est. | 7,855,749 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling (1900–13) British West African pound (1913–14) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

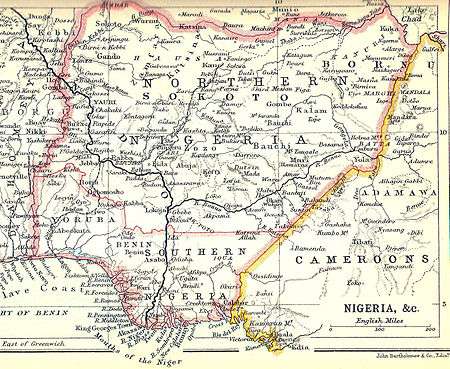

Southern Nigeria was a British protectorate in the coastal areas of modern-day Nigeria formed in 1900 from the union of the Niger Coast Protectorate with territories chartered by the Royal Niger Company below Lokoja on the Niger River.

The Lagos colony was later added in 1906, and the territory was officially renamed the Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria. In 1914, Southern Nigeria was joined with Northern Nigeria Protectorate to form the single colony of Nigeria. The unification was done for economic reasons rather than political—Northern Nigeria Protectorate had a budget deficit; and the colonial administration sought to use the budget surpluses in Southern Nigeria to offset this deficit.[1]

Sir Frederick Lugard, who took office as governor of both protectorates in 1912, was responsible for overseeing the unification, and he became the first governor of the newly united territory. Lugard established several central institutions to anchor the evolving unified structure. A Central Secretariat was instituted at Lagos, which was the seat of government, and the Nigerian Council (later the Legislative Council), was founded to provide a forum for representatives drawn from the provinces. Certain services were integrated across the Northern and Southern Provinces because of their national significance—military, treasury, audit, posts and telegraphs, railways, survey, medical services, judicial and legal departments—and brought under the control of the Central Secretariat in Lagos.[1]

The process of unification was undermined by the persistence of different regional perspectives on governance between the Northern and Southern Provinces, and by Nigerian nationalists in Lagos. While southern colonial administrators welcomed amalgamation as an opportunity for imperial expansion, their counterparts in the Northern Province believed that it was injurious to the interests of the areas they administered because of their relative backwardness and that it was their duty to resist the advance of southern influences and culture into the north. Southerners, on their part, were not eager to embrace the extension of legislation originally meant for the north to the south.[1]

Administration

Governors

From its foundation southern Nigeria was administered by a high commissioner. The first high commissioner was Ralph Moor. When Lagos was amalgamated with the rest of southern Nigeria in 1906, the then high commissioner Walter Egerton was made into Governor of the territory.

When in 1900 the protectorate passed from the Foreign Office to the Colonial Office, Ralph Moor became High Commissioner of Southern Nigeria and laid the foundations of the new administration, his health failing, he retired on pension on 1 October 1903.

Egerton became Governor of Lagos Colony, covering most of the Yoruba lands in the southwest of what is now Nigeria, in 1903. The colonial office wanted to amalgamate the Lagos Colony with the protectorate of Southern Nigeria, and in August 1904 also appointed Egerton as High Commissioner for the Southern Nigeria Protectorate. He held both offices until 28 February 1906.[2] On that date the two territories were formally united and Egerton was appointed Governor of the new Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria, holding office until 1912.[3] In the new Southern Nigeria, the old Lagos Colony became the Western Province, and the former Southern Nigerian Protectorate was split into a Central Province with capital at Warri and an Eastern Province with capital at Calabar.[4]

When his predecessor in Southern Nigeria, Sir Ralph Denham Rayment Moor, resigned, a large part of the southeast of Nigeria was still outside British control. On taking office, Egerton began a policy of sending out annual pacification patrols, which generally obtained submission through the threat of force without being required to actually use force.[5]

When Egerton became Governor of Lagos he enthusiastically endorsed the extension of the Lagos – Ibadan railway onward to Oshogbo, and the project was approved in November 1904. Construction began in January 1905 and the line reached Oshogbo in April 1907.[6] He favored rail over river transport, and pushed to have the railway further extended to Kano by way of Zaria.[7] He also sponsored extensive road construction, building on the legislative foundation laid by his predecessor Moor which enabled use of unpaid local labor.[8] Egerton shared Moor's views on the damage that was being done to the Cross River trade by the combination of indigenous middlemen and traders based in Calabar. The established traders at first got the Colonial Office to pass rules inhibiting competition from traders willing to set up bases further inland, but with some difficulty Egerton persuaded the officials to reverse their ruling.[9]

Egerton was a strong advocate of colonial development. He believed in deficit financing at certain periods of a colony's growth, which was reflected in his budgets from 1906 to 1912. He had a constant struggle to obtain approval for these budgets from the colonial office.[10] As early as 1908, Egerton supported the idea of "a properly organized Agricultural Department with an energetic and experienced head", and the Department of Agriculture came into being in 1910.[11] Egerton endorsed the development of rubber plantations, a concept familiar to him from his time in Malaya, and arranged for land to be leased for this purpose. This was the foundation of a highly successful industry.[12] He also thought there could be great potential in the tin fields near Bauchi, and thought that if proven a branch line to the tin fields would be justified.[13]

Egerton came into conflict with the administration of Northern Nigeria on a number of issues. There was debate over whether Ilorin should be incorporated into Southern Nigeria since the people were Yoruba, or remain in Northern Nigeria since the ruler was Muslim and for some time Ilorin had been subject to the Uthmaniyya Caliphate. There was argument about the administration of duties on goods landed on the coast and carried into Northern Nigeria. And there was dispute over whether railway lines from the north should terminate at Lagos or should take alternative routes to the Niger River and the coast.[14] Egerton had reason on his side in objecting to the proposed line terminating at Baro on the Niger, since navigation southward to the coast was restricted to the high water season, and even then was uncertain.[15]

Egerton's administration imposed policies that tended towards segregation of Europeans and Africans.[16] These included excluding Africans from the West African Medical Service and saying that no European should take orders from an African, which had the effect of ruling out African doctors from serving with the army. Egerton himself did not always approve of these policies, and they were not strictly upheld.[17] The legal relationship between the Lagos government and the Yoruba states of the Lagos Colony was not clear, and it was not until 1908 that Egerton persuaded the Obas to accept the establishment of the Supreme Court in the main towns.[18] In 1912, Egerton was replaced by Frederick Lugard, who was appointed Governor-General of both Southern and Northern Nigeria with the mandate to unite the two. Egerton was appointed Governor of British Guiana as his next posting, clearly a demotion, which may have been connected to his fights with the Colonial Office officials.[19]

Lugard returned to Nigeria as Governor of the two protectorates. His main mission was to complete the amalgamation into one colony. Although controversial in Lagos, where it was opposed by a large section of the political class and the media, the amalgamation did not arouse passion in the rest of the country. From 1914 to 1919, Lugard was made Governor General of the now combined Colony of Nigeria. Throughout his tenure, Lugard sought strenuously to secure the amelioration of the condition of the native people, among other means by the exclusion, wherever possible, of alcoholic liquors, and by the suppression of slave raiding and slavery.

Lugard ran the country with half of each year spent in England, distant from realities in Africa where subordinates had to delay decisions on many matters until he returned, and based his rule on a military system.[20]

| Name | Tenure | Office | Portrait |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sir Ralph Moor | 1900–1903 | High Commissioner of the Southern Nigeria Protectorate |  |

| Sir Walter Egerton | 1903–1912 | High Commissioner of the Southern Nigeria Protectorate 1903–1906 Governor of the Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria 1906–1912 |

|

| Sir Frederick Lugard | 1912–1914 | Governor of the Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria |  |

Economy

Colonial economic policy

The British economic policy for Africa at the time was founded on the belief that if African peoples were brought to embrace European civilisation with its emphasis on law and order their economic resources would be more effectively and thoroughly exploited to the benefit of all. It was optimistically and simplistically believed that the problem of African economic development was largely the problem of law and order; that once the slave trade was suppressed the chaos and anarchy believed to be the bane of life in Africa would disappear and African endeavour would be channeled to the collection of the national produce of the tropical forest for the satisfaction of European needs. The view came to be held that Africans by themselves were incapable of maintaining law and order to the level needed to bring about the much-desired economic revolution, and that only European rule could do it.

It was not enough for the colonial power to impose and maintain law and order though. It was also necessary to promote and develop free movement and natural growth and trade. Also it was the generally accepted assumption that the economic efforts and products of a colony should supplement, rather than compete with or undermine, the economic efforts and products of the metropolitan country. This was a survival of the mercantilist system which had come to grief in the last quarter of the eighteenth century.

| Year | Revenue | Expenditure | Surplus/Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 535,902 | 424,257 | +111,645 |

| 1901 | 606,431 | 564,818 | +41,613 |

| 1902 | 801,737 | 619,687 | +182,050 |

| 1903 | 760,230 | 757,953 | +2,277 |

| 1904 | 888,136 | 863,917 | +24,219 |

| 1905 | 951,748 | 998,564 | -46,816 |

| 1906 | 1,088,717 | 1,056,290 | +32,427 |

| 1907 | 1,459,554 | 1,217,336 | +242,218 |

| 1908 | 1,387,975 | 1,357,763 | +30,212 |

| 1909 | 1,361,891 | 1,648,648 | -286,793 |

| 1910 | 1,933,235 | 1,592,282 | +340,953 |

| 1911 | 1,956,176 | 1,717,259 | +238,917 |

| 1912 | 2,235,412 | 2,110,498 | +124,914 |

| 1913 | 2,668,198 | 2,096,311 | +571,887 |

See also

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Southern Nigeria Protectorate

- Southern Nigeria Government Gazette

References

- 1 2 3 Barkan, Joel D.; Gboyega, Alex; Stevens, Mike (August 2, 2001). "State and Local Governance in Nigeria". Public Sector and Capacity Building Program: Africa Region. The World Bank. p. 1.

March 6, 2011

- ↑ Carland 1985, pp. 82.

- ↑ Worldstatesmen.

- ↑ Afigbo & Falola 2005, pp. 229.

- ↑ Carland 1985, pp. 58.

- ↑ Carland 1985, pp. 148.

- ↑ Carland 1985, pp. 169.

- ↑ Afigbo & Falola 2005, pp. 191.

- ↑ Afigbo & Falola 2005, pp. 177.

- ↑ Carland 1985, pp. 102–104.

- ↑ Falola 2003, pp. 404.

- ↑ Duignan & Gann 1975, pp. 105.

- ↑ Calvert 1910, pp. 37.

- ↑ Afigbo & Falola 2005, pp. 368–369.

- ↑ Geary 1965, pp. 143.

- ↑ Okpewho & Davies 1999, pp. 414.

- ↑ Gann & Duignan 1978, pp. 304.

- ↑ Afigbo & Falola 2005, pp. 280.

- ↑ Carland 1985, pp. 116.

- ↑ The Administration of Nigeria 1900 to 1960, by I. F. Nicholson, Oxford University Press, 1969

- 1 2 Carland 1985, p. 104

- Bibliography

- Carland, John M. (1985). The Colonial Office and Nigeria, 1898-1914. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-8141-9.

- Afigbo, Adiele Eberechukwu; Falola, Toyin (2005). Nigerian history, politics and affairs: the collected essays of Adiele Afigbo. Africa World Press. ISBN 1-59221-324-3.

- Calvert, Albert Frederick (1910). Nigeria and Its Tin Fields. Forgotten Books. ISBN 1-4400-5273-5.

- Carland, John M. (1985). The Colonial Office and Nigeria, 1898–1914. Hoover Press. ISBN 0-8179-8141-1.

- Falola, Toyin (2003). The foundations of Nigeria: essays in honor of Toyin Falola. Africa World Press. ISBN 1-59221-120-8.

- Duignan, Peter; Gann, Lewis H. (1975). Colonialism in Africa, 1870–1960: The economics of colonialism. CUP Archive. ISBN 0-521-08641-8.

- Gann, Lewis H.; Duignan, Peter (1978). The rulers of British Africa, 1870–1914. Routledge. ISBN 0-85664-771-3.

- Geary, William Nevill Montgomerie (1965) [1927]. Nigeria under British rule. Routledge. ISBN 0714616664.

- Okpewho, Isidore; Davies, Carole Boyce (1999). The African diaspora: African origins and New World identities. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33425-X.

- "Nigeria". WorldStatesmen. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

Further reading

- Adiele Afigbo, "Sir Ralph Moor and the Economic Development of Southern Nigeria, 1896–1903", Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, 5/3 (1970), 371–97

- Adiele Afigbo, The Warrant Chiefs: Indirect Rule in Southeastern Nigeria, 1891–1929 (1972)

- Robert Home, City of Blood Revisited: A New Look at the Benin Expedition of 1897 (1982)

- Tekena Tamuno, The Evolution of the Nigerian State: The Southern Phase, 1898–1914 (1972)

- J. C. Anene, Southern Nigeria in Transition, 1885–1906: Theory and Practice in a Colonial Protectorate (1966)

- Obaro Ikime, Merchant Prince of the Niger Delta: The Rise and Fall of Nana Olomu, Last Governor of the Benin River (1968)

Coordinates: 6°27′00″N 3°24′00″E / 6.4500°N 3.4000°E