National Register of Historic Places property types

The U.S. National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) classifies its listings by various types of properties. Listed properties generally fall into one of five categories, though there are special considerations for other types of properties which do not fit into these five broad categories or fit into more specialized subcategories. The five general categories for NRHP properties are: building, structure, object, site, and district.

General categories

Listed properties generally fall into one of five categories, though there are special considerations for other types of properties which do not fit into these five broad categories or fit into more specialized subcategories. The five general categories for NRHP properties are: building, structure, object, site, and district.[1] I When multiple like properties are submitted as a group and listed together, they are known as a Multiple Property Submission.

Building

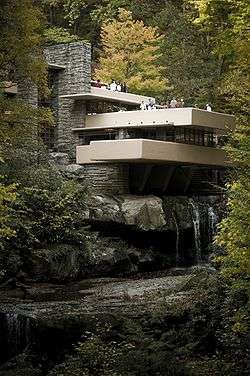

Buildings, as defined by the National Register, are structures intended to shelter some sort of human activity. Examples include a house, barn, hotel, church or similar construction. The term building, as in outbuilding, can be used to refer to historically and functionally related units, such as a courthouse and a jail, or a barn and a house.[1]

Buildings included on the National Register of Historic Places must have all of their basic structural elements as parts of buildings, such as ells and wings; interiors or facades are not independently eligible for the National Register. As such, the whole building is considered during the nomination and its significant features must be identified. If a nominated building has lost any of its basic structural elements, it is considered a ruin and categorized as a site.[1]

Historic districts

The National Register of Historic Places defines a historic district per U.S. federal law, last revised in 2004.[2] According to the Register definition, a historic district is: "a geographically definable area, urban or rural, possessing a significant concentration, linkage, or continuity of sites, buildings, structures, or objects united by past events or aesthetically by plan or physical development. In addition, historic districts consist of contributing and non-contributing properties. Historic districts possess a concentration, linkage or continuity of the other four types of properties. Objects, structures, buildings and sites within a historic district are usually thematically linked by architectural style or designer, date of development, distinctive urban plan, and/or historic associations."[2] For example, the largest collection of houses from 17th and 18th century America are found in the McIntire Historic District in Salem, Massachusetts.[3]

Some NRHP-listed historic districts are further designated as National Historic Landmarks, and termed National Historic Landmark Districts. All National Historic Landmarks are NRHP-listed.

A contributing property is any building, structure, object or site within the boundaries of the district which reflects the significance of the district as a whole, either because of historic associations, historic architectural qualities or archaeological features. Another key aspect of the contributing property is historic integrity. Significant alterations to a property can damage its physical connections with the past, lowering its historic integrity.[4]

Object

Objects are usually artistic in nature, or small in scale when compared to structures and buildings. Though objects may be movable, they are generally associated with a specific setting or environment. Examples of objects include monuments, sculptures and fountains.[1]

Objects considered for inclusion on the NRHP, whether individually or as part of districts, should be designed for a specific location; objects such as transportable sculpture, furniture, and other decorative arts that lack a specific place are discouraged. Fixed outdoor sculpture, an example of public art, is appropriate for inclusion on the Register. The setting of an object is important in relation to the Register. It should be appropriate to its significant historical use, roles, or character. In addition, objects that have been relocated to museums are not considered for inclusion on the Register.[1]

Site

Sites may include discrete areas significant solely for activities in that location in the past, such as battlefields, significant archaeological finds, designed landscapes (parks and gardens), and other locations whose significance is not related to a building or structure.

Sites often possess significance for their potential to yield information in the future, though they are added to the Register under all four of the criteria for inclusion. A sites need not have actual physical remains if it marks the location of a prehistoric or historic event, or if there were no buildings or structures present at the time of the events marked by the site. Site determination requires careful evaluation when the location of prehistoric or historic events cannot be conclusively determined.

Structure

Structures differ from buildings, in that they are functional constructions meant to be used for purposes other than sheltering human activity. Examples include, an aircraft, a ship, a grain elevator, a gazebo and a bridge.

The criteria of significance are applied to nominated structures in much the same fashion as they are for buildings. The basic structural elements must all be intact; no individual parts of the structure are eligible for separate inclusion on the NRHP. An example would be a truss bridge being considered for inclusion. Said truss bridge is composed of metal or wooden truss, abutments and supporting piers; for the property to be considered eligible for the Register, all of these elements must be extant. Structures that have lost their historic configuration or pattern of organization through demolition or deterioration, much like buildings, are considered ruins and classified as sites.[1]

Other categories

There are several other types of properties that do not fall neatly into the categories listed above. The National Park Service publishes a series of bulletins designed to aid in evaluating properties for NRHP eligibility using the criteria for evaluation.[1] Though the criteria for eligibility are always the same, the way they are applied can differ slightly, depending upon the type of property involved. Special Register bulletins cover application of the criteria for evaluation of: aids to navigation, historic battlefields, archaeological sites, aviation properties, cemeteries and burial places, historic designed landscapes, mining sites, post offices, properties associated with significant persons, properties achieving significance within the last 50 years, rural historic landscapes, traditional cultural properties, and vessels and shipwrecks.[1]

Archaeological sites

Archaeological properties are subject to the same four criteria as other properties under consideration for the NRHP. Archaeological sites also must meet at least one of the criteria. Many listed properties which joined the Register under the first, second and fourth criteria contain intact archaeological deposits. Often, these deposits are undocumented, for example a 19th-century farmstead is likely to contain intact, undocumented archaeological deposits.[5]

Maritime sites

By its tenth year, 1976, the National Register listed 46 shipwrecks and vessels.[6] In 1985 Congress mandated that the National Park Service undertake a survey of historic maritime sites, including military sites, in tandem with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the maritime preservation community. The program was known as the National Maritime Initiative.[7] Its goal was to establish priorities for the preservation of maritime resources and recommend roles for the federal government and the private sector in addressing those priorities. The program identified eight categories to which the known maritime resources of the United States would be classified. They included: preserved historic vessels, shipwrecks and hulks (those ships not afloat but not submerged entirely); documentation (logs, journals, charts, photos, etc.); aids to navigation (including coast guard stations and life-saving stations), marine sites and structures (wharves; warehouse, waterfronts, docks, canals, etc.); small craft (less than 40 feet long, less than 20 tons of displacement); artifact collections (fine art, tools, woodwork, parts of vessels, etc.); and intangible cultural resources (shipwright and rigging skills, oral traditions, folklore, etc.).[8]

Traditional cultural properties

1992 amendments to the NHPA allowed for a new designation of property type, that of the traditional cultural property (TCP). The amendments established that properties affiliated with traditional religious and cultural importance to a distinct cultural group, such as a Native American tribe or Native Hawaiian group were eligible for the National Register. TCPs include built or natural locations, areas, or features considered sacred or culturally significant by a group or people. While TCPs are closely associated with Native American Cultures, a site need not be associated with a Native American cultural group to qualify as a TCP for the purposes of the NRHP.[9][10]

The 1992 amendment to the National Historic Preservation Act established "Properties of traditional religious and cultural importance to an Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization" (Section 101(d)(6) of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended in 1992). Thus, Congress established this classification expressly for Native American Tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations. The amendment was clear and explicit, and it did not say anything about any other cultural groups or entities. Also, the term "traditional cultural property" (TCP) is a widely used, but non-legal term coined by agency people - it was never codified or sanctioned by Congress, and it cannot be found in any law or regulation. The agency-invented term traditional cultural property (TCP) is commonly used as a substitute for the actual terminology in the 1992 amendment, but it has also been appropriated for places that have nothing whatsoever to do with Native Americans or Native Hawaiians. Like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, and many other laws and Executive Orders that have been enacted to protect Native American rights specifically, the 1992 amendment to the National Historic Preservation Act was passed expressly on behalf of Native American Tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations, and that is its only legally recognized purpose. See: Advisory Council on Historic Preservation's "Consultation with Indian Tribes in the Section 106 Review Process, a Handbook" (page 19).

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation," (PDF), National Register Bulletins, National Park Service. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- 1 2 Title 36: Section 60.3, Parks Forests and Public Property, Chapter One, Part 60. National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ↑ "McIntire District", Salem Web

- ↑ National Register Historic Districts Q&A, South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ↑ Little, Barbara, Seibert, Erika Martin, et al. "Guidelines for Evaluating and Registering Archaeological Properties", (Section IV - Evaluating the Significance of Archaeological Properties), National Register Bulletin, National Register Publication, National Park Service, 2000. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ↑ Delgado, James P. (1987). "The National Register of Historic Places and Maritime Preservation". APT Bulletin 19 (1): 34–39. JSTOR 1494176.

- ↑ Delgado, James P. "The National Maritime Initiative: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Maritime Preservation (in Preservation Technology)", The Public Historian, Vol. 13, No. 3, Preservation Technology. (Summer, 1991), pp. 75-84. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ↑ Wall, Glennie Murray (1987). "The National Maritime Initiative". APT Bulletin 19 (1): 2–3, 18. JSTOR 1494168.

- ↑ A German critique about the concept of 'Traditional Cultural Properties', see: Michael Falser: Denkmalpflege und nationale Identität in den USA: Vom exklusiven Kulturerbe zum Konzept des ‚Traditional Cultural Property’. In: Köth, A., Krauskopf, K., Schwarting, A.(Eds.) Building America. Vol 2 (Migration der Bilder). Dresden 2007, pp. 299-324.

- ↑ Ferguson, T. J. "Native Americans and the Practice of Archaeology," (JSTOR), Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 25. (1996), pp. 63-79. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||