Probability space

| Part of a series on Statistics |

| Probability theory |

|---|

|

In probability theory, a probability space or a probability triple is a mathematical construct that models a real-world process (or "experiment") consisting of states that occur randomly. A probability space is constructed with a specific kind of situation or experiment in mind. One proposes that each time a situation of that kind arises, the set of possible outcomes is the same and the probabilities are also the same.

A probability space consists of three parts:[1][2]

- A sample space,

, which is the set of all possible outcomes.

, which is the set of all possible outcomes. - A set of events

, where each event is a set containing zero or more outcomes.

, where each event is a set containing zero or more outcomes. - The assignment of probabilities to the events; that is, a function

from events to probabilities.

from events to probabilities.

An outcome is the result of a single execution of the model. Since individual outcomes might be of little practical use, more complex events are used to characterize groups of outcomes. The collection of all such events is a σ-algebra  . Finally, there is a need to specify each event's likelihood of happening. This is done using the probability measure function,

. Finally, there is a need to specify each event's likelihood of happening. This is done using the probability measure function,  .

.

Once the probability space is established, it is assumed that “nature” makes its move and selects a single outcome,  , from the sample space

, from the sample space  . All the events in

. All the events in  that contain the selected outcome

that contain the selected outcome  (recall that each event is a subset of

(recall that each event is a subset of  ) are said to “have occurred”. The selection performed by nature is done in such a way that if the experiment were to be repeated an infinite number of times, the relative frequencies of occurrence of each of the events would coincide with the probabilities prescribed by the function

) are said to “have occurred”. The selection performed by nature is done in such a way that if the experiment were to be repeated an infinite number of times, the relative frequencies of occurrence of each of the events would coincide with the probabilities prescribed by the function  .

.

The Russian mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov introduced the notion of probability space, together with other axioms of probability, in the 1930s. Nowadays alternative approaches for axiomatization of probability theory exist; see “Algebra of random variables”, for example.

This article is concerned with the mathematics of manipulating probabilities. The article probability interpretations outlines several alternative views of what "probability" means and how it should be interpreted. In addition, there have been attempts to construct theories for quantities that are notionally similar to probabilities but do not obey all their rules; see, for example, Free probability, Fuzzy logic, Possibility theory, Negative probability and Quantum probability.

Introduction

A probability space is a mathematical triplet  that

presents a model for a particular class of real-world situations.

As with other models, its author ultimately defines which elements

that

presents a model for a particular class of real-world situations.

As with other models, its author ultimately defines which elements  ,

,  , and

, and  will contain.

will contain.

- The sample space

is a set of outcomes. An outcome is the result of a single execution of the model. Outcomes may be states of nature, possibilities, experimental results and the like. Every instance of the real-world situation (or run of the experiment) must produce exactly one outcome. If outcomes of different runs of an experiment differ in any way that matters, they are distinct outcomes. Which differences matter depends on the kind of analysis we want to do: This leads to different choices of sample space.

is a set of outcomes. An outcome is the result of a single execution of the model. Outcomes may be states of nature, possibilities, experimental results and the like. Every instance of the real-world situation (or run of the experiment) must produce exactly one outcome. If outcomes of different runs of an experiment differ in any way that matters, they are distinct outcomes. Which differences matter depends on the kind of analysis we want to do: This leads to different choices of sample space. - The σ-algebra

is a collection of all the events (not necessarily elementary) we would like to consider. Here, an "event" is a set of zero or more outcomes, i.e., a subset of the sample space. An event is considered to have "happened" during an experiment when the outcome of the latter is an element of the event. Since the same outcome may be a member of many events, it is possible for many events to have happened given a single outcome. For example, when the trial consists of throwing two dice, the set of all outcomes with a sum of 7 pips may constitute an event, whereas outcomes with an odd number of pips may constitute another event. If the outcome is the element of the elementary event of two pips on the first die and five on the second, then both of the events, "7 pips" and "odd number of pips", are said to have happened.

is a collection of all the events (not necessarily elementary) we would like to consider. Here, an "event" is a set of zero or more outcomes, i.e., a subset of the sample space. An event is considered to have "happened" during an experiment when the outcome of the latter is an element of the event. Since the same outcome may be a member of many events, it is possible for many events to have happened given a single outcome. For example, when the trial consists of throwing two dice, the set of all outcomes with a sum of 7 pips may constitute an event, whereas outcomes with an odd number of pips may constitute another event. If the outcome is the element of the elementary event of two pips on the first die and five on the second, then both of the events, "7 pips" and "odd number of pips", are said to have happened. - The probability measure

is a function returning an event's probability. A probability is a real number between zero (impossible events have probability zero, though probability-zero events are not necessarily impossible) and one (the event happens almost surely, with total certainty). Thus

is a function returning an event's probability. A probability is a real number between zero (impossible events have probability zero, though probability-zero events are not necessarily impossible) and one (the event happens almost surely, with total certainty). Thus  is a function

is a function ![P:\mathcal{F} \rightarrow [0,1]](../I/m/f4c42f02e64a2f6f7d8692ea48e53b02.png) . The probability measure function must satisfy two simple requirements: First, the probability of a countable union of mutually exclusive events must be equal to the countable sum of the probabilities of each of these events. For example, the probability of the union of the mutually exclusive events

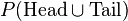

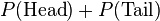

. The probability measure function must satisfy two simple requirements: First, the probability of a countable union of mutually exclusive events must be equal to the countable sum of the probabilities of each of these events. For example, the probability of the union of the mutually exclusive events  and

and  in the random experiment of one coin toss,

in the random experiment of one coin toss,  , is the sum of probability for

, is the sum of probability for  and the probability for

and the probability for  ,

,  . Second, the probability of the sample space

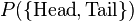

. Second, the probability of the sample space  must be equal to 1 (which accounts for the fact that, given an execution of the model, some outcome must occur). In the previous example the probability of the set of outcomes

must be equal to 1 (which accounts for the fact that, given an execution of the model, some outcome must occur). In the previous example the probability of the set of outcomes  must be equal to one, because it is entirely certain that the outcome will be either

must be equal to one, because it is entirely certain that the outcome will be either  or

or  (the model neglects any other possibility) in a single coin toss.

(the model neglects any other possibility) in a single coin toss.

Not every subset of the sample space  must necessarily be considered an event: some of the subsets are simply not of interest, others cannot be "measured". This is not so obvious in a case like a coin toss. In a different example, one could consider javelin throw lengths, where the events typically are intervals like "between 60 and 65 meters" and unions of such intervals, but not sets like the "irrational numbers between 60 and 65 meters"

must necessarily be considered an event: some of the subsets are simply not of interest, others cannot be "measured". This is not so obvious in a case like a coin toss. In a different example, one could consider javelin throw lengths, where the events typically are intervals like "between 60 and 65 meters" and unions of such intervals, but not sets like the "irrational numbers between 60 and 65 meters"

Definition

In short, a probability space is a measure space such that the measure of the whole space is equal to one.

The expanded definition is the following: a probability space is a triple  consisting of:

consisting of:

- the sample space

— an arbitrary non-empty set,

— an arbitrary non-empty set, - the σ-algebra

(also called σ-field) — a set of subsets of

(also called σ-field) — a set of subsets of  , called events, such that:

, called events, such that:

-

contains the sample space:

contains the sample space:  ,

, -

is closed under complements: if

is closed under complements: if  , then also

, then also  ,

, -

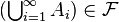

is closed under countable unions: if

is closed under countable unions: if  for

for  , then also

, then also

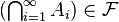

- The corollary from the previous two properties and De Morgan’s law is that

is also closed under countable intersections: if

is also closed under countable intersections: if  for

for  , then also

, then also

- The corollary from the previous two properties and De Morgan’s law is that

-

- the probability measure

![P:\mathcal{F}\to[0,1]](../I/m/112c6c695c6a3a302e265716ea954864.png) — a function on

— a function on  such that:

such that:

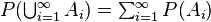

- P is countably additive: if

is a countable collection of pairwise disjoint sets, then

is a countable collection of pairwise disjoint sets, then  ,

, - the measure of entire sample space is equal to one:

.

.

- P is countably additive: if

Discrete case

Discrete probability theory needs only at most countable sample spaces  . Probabilities can be ascribed to points of

. Probabilities can be ascribed to points of  by the probability mass function

by the probability mass function ![p:\Omega\to[0,1]](../I/m/e0d27881aa8b1a5cbd5b53bc0ef16149.png) such that

such that  . All subsets of

. All subsets of  can be treated as events (thus,

can be treated as events (thus,  is the power set). The probability measure takes the simple form

is the power set). The probability measure takes the simple form

The greatest σ-algebra

The greatest σ-algebra  describes the complete information. In general, a σ-algebra

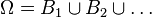

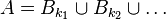

describes the complete information. In general, a σ-algebra  corresponds to a finite or countable partition

corresponds to a finite or countable partition  , the general form of an event

, the general form of an event  being

being  . See also the examples.

. See also the examples.

The case  is permitted by the definition, but rarely used, since such

is permitted by the definition, but rarely used, since such  can safely be excluded from the sample space.

can safely be excluded from the sample space.

General case

If Ω is uncountable, still, it may happen that p(ω) ≠ 0 for some ω; such ω are called atoms. They are an at most countable (maybe empty) set, whose probability is the sum of probabilities of all atoms. If this sum is equal to 1 then all other points can safely be excluded from the sample space, returning us to the discrete case. Otherwise, if the sum of probabilities of all atoms is less than 1 (maybe 0), then the probability space decomposes into a discrete (atomic) part (maybe empty) and a non-atomic part.

Non-atomic case

If p(ω) = 0 for all ω∈Ω (in this case, Ω must be uncountable, because otherwise P(Ω)=1 could not be satisfied), then equation (∗) fails: the probability of a set is not the sum over its elements, as summation is only defined for countable amount of elements. This makes the probability space theory much more technical. A formulation stronger than summation, measure theory is applicable. Initially the probabilities are ascribed to some “generator” sets (see the examples). Then a limiting procedure allows assigning probabilities to sets that are limits of sequences of generator sets, or limits of limits, and so on. All these sets are the σ-algebra  . For technical details see Carathéodory's extension theorem. Sets belonging to

. For technical details see Carathéodory's extension theorem. Sets belonging to  are called measurable. In general they are much more complicated than generator sets, but much better than non-measurable sets.

are called measurable. In general they are much more complicated than generator sets, but much better than non-measurable sets.

Complete probability space

A probability space  is said to be a complete probability space if for all

is said to be a complete probability space if for all  with

with  and all

and all  one has

one has  . Often, the study of probability spaces is restricted to complete probability spaces.

. Often, the study of probability spaces is restricted to complete probability spaces.

Examples

Discrete examples

Example 1

If the experiment consists of just one flip of a perfect coin, then the outcomes are either heads or tails: Ω = {H, T}. The σ-algebra  = 2Ω contains 2² = 4 events, namely: {H} – “heads”, {T} – “tails”, {} – “neither heads nor tails”, and {H,T} – “either heads or tails”. So,

= 2Ω contains 2² = 4 events, namely: {H} – “heads”, {T} – “tails”, {} – “neither heads nor tails”, and {H,T} – “either heads or tails”. So,  = {{}, {H}, {T}, {H,T}}. There is a fifty percent chance of tossing heads, and fifty percent for tails. Thus the probability measure in this example is P({}) = 0, P({H}) = 0.5, P({T}) = 0.5, P({H,T}) = 1.

= {{}, {H}, {T}, {H,T}}. There is a fifty percent chance of tossing heads, and fifty percent for tails. Thus the probability measure in this example is P({}) = 0, P({H}) = 0.5, P({T}) = 0.5, P({H,T}) = 1.

Example 2

The fair coin is tossed three times. There are 8 possible outcomes: Ω = {HHH, HHT, HTH, HTT, THH, THT, TTH, TTT} (here “HTH” for example means that first time the coin landed heads, the second time tails, and the last time heads again). The complete information is described by the σ-algebra  = 2Ω of 28 = 256 events, where each of the events is a subset of Ω.

= 2Ω of 28 = 256 events, where each of the events is a subset of Ω.

Alice knows the outcome of the second toss only. Thus her incomplete information is described by the partition Ω = A1 ⊔ A2 = {HHH, HHT, THH, THT} ⊔ {HTH, HTT, TTH, TTT}, and the corresponding σ-algebra  Alice = {{}, A1, A2, Ω}. Brian knows only the total number of tails. His partition contains four parts: Ω = B0 ⊔ B1 ⊔ B2 ⊔ B3 = {HHH} ⊔ {HHT, HTH, THH} ⊔ {TTH, THT, HTT} ⊔ {TTT}; accordingly, his σ-algebra

Alice = {{}, A1, A2, Ω}. Brian knows only the total number of tails. His partition contains four parts: Ω = B0 ⊔ B1 ⊔ B2 ⊔ B3 = {HHH} ⊔ {HHT, HTH, THH} ⊔ {TTH, THT, HTT} ⊔ {TTT}; accordingly, his σ-algebra  Brian contains 24 = 16 events.

Brian contains 24 = 16 events.

The two σ-algebras are incomparable: neither  Alice ⊆

Alice ⊆  Brian nor

Brian nor  Brian ⊆

Brian ⊆  Alice; both are sub-σ-algebras of 2Ω.

Alice; both are sub-σ-algebras of 2Ω.

Example 3

If 100 voters are to be drawn randomly from among all voters in California and asked whom they will vote for governor, then the set of all sequences of 100 Californian voters would be the sample space Ω. We assume that sampling without replacement is used: only sequences of 100 different voters are allowed. For simplicity an ordered sample is considered, that is a sequence {Alice, Brian} is different from {Brian, Alice}. We also take for granted that each potential voter knows exactly his/her future choice, that is he/she doesn’t choose randomly.

Alice knows only whether or not Arnold Schwarzenegger has received at least 60 votes. Her incomplete information is described by the σ-algebra  Alice that contains: (1) the set of all sequences in Ω where at least 60 people vote for Schwarzenegger; (2) the set of all sequences where fewer than 60 vote for Schwarzenegger; (3) the whole sample space Ω; and (4) the empty set ∅.

Alice that contains: (1) the set of all sequences in Ω where at least 60 people vote for Schwarzenegger; (2) the set of all sequences where fewer than 60 vote for Schwarzenegger; (3) the whole sample space Ω; and (4) the empty set ∅.

Brian knows the exact number of voters who are going to vote for Schwarzenegger. His incomplete information is described by the corresponding partition Ω = B0 ⊔ B1 ... ⊔ B100 (though some of these sets may be empty, depending on the Californian voters...) and the σ-algebra  Brian consists of 2101 events.

Brian consists of 2101 events.

In this case Alice’s σ-algebra is a subset of Brian’s:  Alice ⊂

Alice ⊂  Brian. The Brian’s σ-algebra is in turn the subset of the much larger “complete information” σ-algebra 2Ω consisting of 2n(n−1)...(n−99) events, where n is the number of all potential voters in California.

Brian. The Brian’s σ-algebra is in turn the subset of the much larger “complete information” σ-algebra 2Ω consisting of 2n(n−1)...(n−99) events, where n is the number of all potential voters in California.

Non-atomic examples

Example 4

A number between 0 and 1 is chosen at random, uniformly. Here Ω = [0,1],  is the σ-algebra of Borel sets on Ω, and P is the Lebesgue measure on [0,1].

is the σ-algebra of Borel sets on Ω, and P is the Lebesgue measure on [0,1].

In this case the open intervals of the form (a,b), where 0 < a < b < 1, could be taken as the generator sets. Each such set can be ascribed the probability of P((a,b)) = (b − a), which generates the Lebesgue measure on [0,1], and the Borel σ-algebra on Ω.

Example 5

A fair coin is tossed endlessly. Here one can take Ω = {0,1}∞, the set of all infinite sequences of numbers 0 and 1. Cylinder sets {(x1, x2, ...) ∈ Ω : x1 = a1, ..., xn = an} may be used as the generator sets. Each such set describes an event in which the first n tosses have resulted in a fixed sequence (a1, ..., an), and the rest of the sequence may be arbitrary. Each such event can be naturally given the probability of 2−n.

These two non-atomic examples are closely related: a sequence (x1,x2,...) ∈ {0,1}∞ leads to the number 2−1x1 + 2−2x2 + ... ∈ [0,1]. This is not a one-to-one correspondence between {0,1}∞ and [0,1] however: it is an isomorphism modulo zero, which allows for treating the two probability spaces as two forms of the same probability space. In fact, all non-pathologic non-atomic probability spaces are the same in this sense. They are so-called standard probability spaces. Basic applications of probability spaces are insensitive to standardness. However, non-discrete conditioning is easy and natural on standard probability spaces, otherwise it becomes obscure.

Related concepts

Probability distribution

Any probability distribution defines a probability measure.

Random variables

A random variable X is a measurable function X: Ω→S from the sample space Ω to another measurable space S called the state space.

The notation Pr(X∈A) is a commonly used shorthand for P({ω∈Ω: X(ω)∈A}).

Defining the events in terms of the sample space

If Ω is countable we almost always define  as the power set of Ω, i.e.

as the power set of Ω, i.e.  = 2Ω which is trivially a σ-algebra and the biggest one we can create using Ω. We can therefore omit

= 2Ω which is trivially a σ-algebra and the biggest one we can create using Ω. We can therefore omit  and just write (Ω,P) to define the probability space.

and just write (Ω,P) to define the probability space.

On the other hand, if Ω is uncountable and we use  = 2Ω we get into trouble defining our probability measure P because

= 2Ω we get into trouble defining our probability measure P because  is too “large”, i.e. there will often be sets to which it will be impossible to assign a unique measure. In this case, we have to use a smaller σ-algebra

is too “large”, i.e. there will often be sets to which it will be impossible to assign a unique measure. In this case, we have to use a smaller σ-algebra  , for example the Borel algebra of Ω, which is the smallest σ-algebra that makes all open sets measurable.

, for example the Borel algebra of Ω, which is the smallest σ-algebra that makes all open sets measurable.

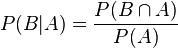

Conditional probability

Kolmogorov’s definition of probability spaces gives rise to the natural concept of conditional probability. Every set A with non-zero probability (that is, P(A) > 0) defines another probability measure

on the space. This is usually pronounced as the “probability of B given A”.

For any event B such that P(B) > 0 the function Q defined by Q(A) = P(A|B) for all events A is itself a probability measure.

Independence

Two events, A and B are said to be independent if P(A∩B)=P(A)P(B).

Two random variables, X and Y, are said to be independent if any event defined in terms of X is independent of any event defined in terms of Y. Formally, they generate independent σ-algebras, where two σ-algebras G and H, which are subsets of F are said to be independent if any element of G is independent of any element of H.

Mutual exclusivity

Two events, A and B are said to be mutually exclusive or disjoint if P(A∩B) = 0. (This is weaker than A∩B = ∅, which is the definition of disjoint for sets).

If A and B are disjoint events, then P(A∪B) = P(A) + P(B). This extends to a (finite or countably infinite) sequence of events. However, the probability of the union of an uncountable set of events is not the sum of their probabilities. For example, if Z is a normally distributed random variable, then P(Z=x) is 0 for any x, but P(Z∈R) = 1.

The event A∩B is referred to as “A and B”, and the event A∪B as “A or B”.

See also

- σ-algebra

- Space (mathematics)

- Measure space

- Fuzzy measure theory

- Filtered probability space

- Talagrand's concentration inequality

References

Bibliography

- Pierre Simon de Laplace (1812) Analytical Theory of Probability

- The first major treatise blending calculus with probability theory, originally in French: Théorie Analytique des Probabilités.

- Andrei Nikolajevich Kolmogorov (1950) Foundations of the Theory of Probability

- The modern measure-theoretic foundation of probability theory; the original German version (Grundbegriffe der Wahrscheinlichkeitrechnung) appeared in 1933.

- Harold Jeffreys (1939) The Theory of Probability

- An empiricist, Bayesian approach to the foundations of probability theory.

- Edward Nelson (1987) Radically Elementary Probability Theory

- Discrete foundations of probability theory, based on nonstandard analysis and internal set theory. downloadable. http://www.math.princeton.edu/~nelson/books.html

- Patrick Billingsley: Probability and Measure, John Wiley and Sons, New York, Toronto, London, 1979.

- Henk Tijms (2004) Understanding Probability

- A lively introduction to probability theory for the beginner, Cambridge Univ. Press.

- David Williams (1991) Probability with martingales

- An undergraduate introduction to measure-theoretic probability, Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Gut, Allan (2005). Probability: A Graduate Course. Springer. ISBN 0-387-22833-0.

External links

- Sazonov, V.V. (2001), "Probability space", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Animation demonstrating probability space of dice

- Virtual Laboratories in Probability and Statistics (principal author Kyle Siegrist), especially, Probability Spaces

- Citizendium

- Complete probability space

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Probability space", MathWorld.