Proxemics

Proxemics is the study of the spatial requirements of humans and the effects of population density on behavior, communication, and social interaction.[1]

Overview

Proxemics is one of several subcategories of the study of nonverbal communication.

Other prominent subcategories of nonverbal communication include haptics (touch), kinesics (body movement), vocalics (paralanguage), and chronemics (structure of time).[2]

Proxemics can be defined as "the interrelated observations and theories of man's use of space as a specialized elaboration of culture".[3] Edward T. Hall, the cultural anthropologist who coined the term in 1963, emphasized the impact of proxemic behavior (the use of space) on interpersonal communication. Hall believed that the value in studying proxemics comes from its applicability in evaluating not only the way people interact with others in daily life, but also "the organization of space in [their] houses and buildings, and ultimately the layout of [their] towns".[4]

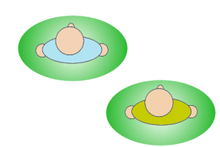

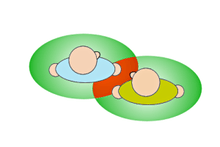

In his work on proxemics, Hall separated his theory into two overarching categories: personal space and territory. Personal space describes the immediate space surrounding a person, while territory refers to the area which a person may "lay claim to" and defend against others.[2]

Personal space

Personal space is the region surrounding a person which they regard as psychologically theirs. Most people value their personal space and feel discomfort, anger, or anxiety when their personal space is encroached.[5] Permitting a person to enter personal space and entering somebody else's personal space are indicators of perception of those people's relationship. An intimate zone is reserved for close friends, lovers, children and close family members. Another zone is used for conversations with friends, to chat with associates, and in group discussions. A further zone is reserved for strangers, newly formed groups, and new acquaintances. A fourth zone is used for speeches, lectures, and theater; essentially, public distance is that range reserved for larger audiences.[6]

Entering somebody's personal space is normally an indication of familiarity and sometimes intimacy. However, in modern society, especially in crowded urban communities, it can be difficult to maintain personal space, for example when in a crowded train, elevator or street. Many people find such physical proximity to be psychologically disturbing and uncomfortable,[5] though it is accepted as a fact of modern life. In an impersonal, crowded situation, eye contact tends to be avoided. Even in a crowded place, preserving personal space is important, and intimate and sexual contact, such as frotteurism and groping, is unacceptable physical contact.

The amygdala is suspected of processing people's strong reactions to personal space violations since these are absent in those in which it is damaged and it is activated when people are physically close.[7] Research links the amygdala with emotional reactions to proximity to other people. First, it is activated by such proximity, and second, in those with complete bilateral damage to their amygdala, such as patient S.M., lack a sense of personal space boundary.[7] As the researchers have noted: "Our findings suggest that the amygdala may mediate the repulsive force that helps to maintain a minimum distance between people. Further, our findings are consistent with those in monkeys with bilateral amygdala lesions, who stay within closer proximity to other monkeys or people, an effect we suggest arises from the absence of strong emotional responses to personal space violation."[7]

A person's personal space is carried with them everywhere they go. It is the most inviolate form of territory.[8] Body spacing and posture, according to Hall, are unintentional reactions to sensory fluctuations or shifts, such as subtle changes in the sound and pitch of a person's voice. Social distance between people is reliably correlated with physical distance, as are intimate and personal distance, according to the delineations below. Hall did not mean for these measurements to be strict guidelines that translate precisely to human behavior, but rather a system for gauging the effect of distance on communication and how the effect varies between cultures and other environmental factors.

- Intimate distance for embracing, touching or whispering

- Close phase – less than 6 inches (15 cm)

- Far phase – 6 to 18 inches (15 to 46 cm)

- Personal distance for interactions among good friends or family

- Close phase – 1.5 to 2.5 feet (46 to 76 cm)

- Far phase – 2.5 to 4 feet (76 to 122 cm)

- Social distance for interactions among acquaintances

- Close phase – 4 to 7 feet (1.2 to 2.1 m)

- Far phase – 7 to 12 feet (2.1 to 3.7 m)

- Public distance used for public speaking

- Close phase – 12 to 25 feet (3.7 to 7.6 m)

- Far phase – 25 feet (7.6 m) or more.

In addition to physical distance, the level of intimacy between conversants can be determined by "socio-petal socio-fugal axis", or the "angle formed by the axis of the conversants' shoulders".[2] Hall has also studied combinations of postures between dyads (two people) including lying prone, sitting, or standing. These variations in positioning are impacted by a variety of nonverbal communicative factors, listed below.

- Kinesthetic factors: This category deals with how closely the participants are to touching, from being completely outside of body-contact distance to being in physical contact, which parts of the body are in contact, and body part positioning.

- Touching code: This behavioural category concerns how participants are touching one another, such as caressing, holding, feeling, prolonged holding, spot touching, pressing against, accidental brushing, or not touching at all.

- Visual code: This category denotes the amount of eye contact between participants. Four sub-categories are defined, ranging from eye-to-eye contact to no eye contact at all.

- Thermal code: This category denotes the amount of body heat that each participant perceives from another. Four sub-categories are defined: conducted heat detected, radiant heat detected, heat probably detected, and no detection of heat.

- Olfactory code: This category deals in the kind and degree of odour detected by each participant from the other.

- Voice loudness: This category deals in the vocal effort used in speech. Seven sub-categories are defined: silent, very soft, soft, normal, normal+, loud, and very loud.

Cultural factors

Hall notes that different cultures maintain different standards of personal space. The Francavilla Model of Cultural Types indicates the variations in personal interactive qualities, indicating three poles: "linear-active" cultures, which are characterized as cool and decisive (Germany, Norway, USA), "reactive" cultures, characterized as accommodating and non-confrontational (Vietnam, China, Japan), and "multi-active" cultures, characterized as warm and impulsive (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Italy).[9] Realizing and recognizing these cultural differences improves cross-cultural understanding, and helps eliminate discomfort people may feel if the interpersonal distance is too large ("stand-offish") or too small (intrusive).

Personal space is highly variable, and can be due to cultural differences and personal experiences. The United States shows considerable similarities to that in northern and central European regions, such as Germany, the Benelux, Scandinavia and the United Kingdom. The main difference is that residents of the United States of America like to keep more open space between themselves and their conversation partners (roughly 4 feet (1.2 m) compared to 2 to 3 feet (0.6–0.9 m) in Europe).[10] Greeting rituals tend to be the same in these regions and in the United States, consisting of minimal body contact which often remains confined to a simple handshake.

Those living in a densely populated places tend to have a lower expectation of personal space. Residents of India or Japan tend to have a smaller personal space than those in the Mongolian steppe, both in regard to home and individual spaces. Difficulties can be created by failures of intercultural communication due to different expectations of personal space.[5] For a more detailed example, see Body contact and personal space in the United States.

In European culture, personal space has changed historically since Roman times, along with the boundaries of public and private space. This topic has been explored in A History of Private Life (2001), under the general editorship of Philippe Ariès and Georges Duby.[11]

Personal space is also affected by a person's position in society, with more affluent individuals expecting a larger personal space.

People make exceptions to and modify their space requirements. A number of relationships may allow for personal space to be modified, including familial ties, romantic partners, friendships and close acquaintances, where there is a greater degree of trust and personal knowledge. In addition, under certain circumstances, when normal space requirements simply cannot be met, such as in public transit or elevators, personal space requirements are modified accordingly.

Adaptation

According to the psychologist Robert Sommer, one method of dealing with violated personal space is dehumanization. He argues that on the subway, crowded people often imagine those intruding on their personal space as inanimate. Behavior is another method: a person attempting to talk to someone can often cause situations where one person steps forward to enter what they perceive as a conversational distance, and the person they are talking to can step back to restore their personal space.

Neuropsychological space

Neuropsychology describes personal space in terms of the kinds of "nearness" to the body.

- Extrapersonal space: The space that occurs outside the reach of an individual.

- Peripersonal space: The space within reach of any limb of an individual. Thus, to be "within arm's length" is to be within one's peripersonal space.

- Pericutaneous space: The space just outside our bodies but which might be near to touching it. Visual-tactile perceptive fields overlap in processing this space. For example, an individual might see a feather as not touching their skin but still experience the sensation of being tickled when it hovers just above their hand. Other examples include the blowing of wind, gusts of air, and the passage of heat.[12]

Previc[13] further subdivides extrapersonal space into focal-extrapersonal space, action-extrapersonal space, and ambient-extrapersonal space. Focal-extrapersonal space is located in the lateral temporo-frontal pathways at the center of our vision, is retinotopically centered and tied to the position of our eyes, and is involved in object search and recognition. Action-extrapersonal-space is located in the medial temporo-frontal pathways, spans the entire space, and is head-centered and involved in orientation and locomotion in topographical space. Action-extrapersonal space provides the "presence" of our world. Ambient-extrapersonal space initially courses through the peripheral parieto-occipital visual pathways before joining up with vestibular and other body senses to control posture and orientation in earth-fixed/gravitational space. Numerous studies involving peripersonal and extrapersonal neglect have shown that peripersonal space is located dorsally in the parietal lobe whereas extrapersonal space is housed ventrally in the temporal lobe.

Territory

There are four forms of human territory in proxemic theory. They are:

- Public territory: a place where one may freely enter. This type of territory is rarely in the constant control of just one person. However, people might come to temporarily own areas of public territory.

- Interactional territory: a place where people congregate informally

- Home territory: a place where people continuously have control over their individual territory

- Body territory: the space immediately surrounding us

These different levels of territory, in addition to factors involving personal space, suggest ways for us to communicate and produce expectations of appropriate behavior.[14]

Applied research

In developing new communication technologies, the theory of proxemics is often considered. While physical proximity cannot be achieved when people are connected virtually, perceived proximity can be attempted, and several studies have shown that it is a crucial indicator in the effectiveness of virtual communication technologies.[15][16][17][18] These studies suggest that various individual and situational factors influence how close we feel to another person, regardless of distance. The mere-exposure effect originally referred to the tendency of a person to positively favor those who they have been physically exposed to most often.[19] However, recent research has extended this effect to virtual communication. This work suggests that the more someone communicates virtually with another person, the more he is able to envision that person's appearance and workspace, therefore fostering a sense of personal connection.[15] Increased communication has also been seen to foster common ground, or the feeling of identification with another, which leads to positive attributions about that person. Some studies emphasize the importance of shared physical territory in achieving common ground,[20] while others find that common ground can be achieved virtually, by communicating often.[15]

Much research in the fields of Communication, Psychology, and Sociology, especially under the category of Organizational Behavior, has shown that physical proximity enhances peoples' ability to work together. Face-to-face interaction is often used as a tool to maintain the culture, authority, and norms of an organization or workplace.[21][22] An extensive body of research has been written about how proximity is affected by the use of new communication technologies. The importance of physical proximity in co-workers is often emphasized.

Cinema

Proxemics is an essential component of cinematic mise-en-scène, the placement of characters, props and scenery within a frame, creating visual weight and movement.[23] There are two aspects to the consideration of proxemics in this context, the first being character proxemics, which addresses such questions as: How much space is there between the characters? What is suggested by characters who are close to (or, conversely, far away from) each other? Do distances change as the film progresses? and, Do distances depend on the film's other content?[24] The other consideration is camera proxemics, which answers the single question: How far away is the camera from the characters/action?[25] Analysis of camera proxemics typically relates Hall's system of proxemic patterns to the camera angle used to create a specific shot, with the long shot or extreme long shot becoming the public proxemic, a full shot (sometimes called a figure shot, complete view, or medium long shot) becoming the social proxemic, the medium shot becoming the personal proxemic, and the close up or extreme close up becoming the intimate proxemic.[26]

-

A long shot—the public proxemic

-

A full shot—the social proxemic

-

A medium shot—the personal proxemic

-

A close-up—the intimate proxemic

Film analyst Louis Giannetti has maintained that, in general, the greater the distance between the camera and the subject (in other words, the public proxemic), the more emotionally neutral the audience remains, whereas the closer the camera is to a character, the greater the audience's emotional attachment to that character.[27] Or, as actor/director Charlie Chaplin put it: “Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long shot.”[28]

Proxemics in debate

Proxemics is an especially prominent tool deployed in competitive speech and debate. In particular, its use is integral to competitive policy debate. The use of proxemics in policy debate was popularized by Matt Struth, a PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota and policy debate icon, in 2015.[29] Struth philosophized that proxemics in the debate space, via strategically adjusting your spacing to accommodate judges and gain an advantage over your opponents, is equally as important as the actual content of your argumentation. Since its diffusion to the debate community, proxemics has become the calling card of advanced debate skills and is something that judges seek out when evaluating persuasiveness.

See also

References

- ↑ "Proxemics". Dictionary.com. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Moore, Nina (2010). Nonverbal Communication:Studies and Applications. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Hall, Edward T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-08476-5.

- ↑ Hall, Edward T. (October 1963). "A System for the Notation of Proxemic Behavior". American Anthropologist 65 (5): 1003–1026. doi:10.1525/aa.1963.65.5.02a00020.

- 1 2 3 Hall, Edward T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-08476-5.

- ↑ Engleberg, Isa N. Working in Groups: Communication Principles and Strategies. My Communication Kit Series, 2006. page 140-141

- 1 2 3 Kennedy DP, Gläscher J, Tyszka JM, Adolphs R. (2009). Personal space regulation by the human amygdala. Nat Neurosci. 12:1226-1227. PMID 19718035 doi:10.1038/nn.2381

- ↑ Richmond, Virginia (2008). Nonverbal Behavior in Interpersonal Relations. Boston: Pearson/A and B. p. 130. ISBN 9780205042302.

- ↑ Lewis, Richard. "Cross-Culture". Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ Histoire de la vie privée (2001), editors Philippe Ariès and Georges Duby; le Grand livre du mois. ISBN 978-2020364171. Published in English as A History of Private Life by the Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674399747.

- ↑ Elias, L.J., M.S., Saucier, (2006) Neuropsychology: Clinical and Experimental Foundations. Boston; MA. Pearson Education Inc. ISBN 0-205-34361-9

- ↑ Previc, F.H. (1998). "The neuropsychology of 3D space". Psychol. Bull. 124 (2): 123–164. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.123. PMID 9747184.

- ↑ Lyman, S.M.; Scott, M.B. (1967). "Territoriality: A Neglected Sociological Dimension". Social Problems 15: 236–249. doi:10.1525/sp.1967.15.2.03a00090.

- 1 2 3 O'Leary, Michael Boyer; Wilson, Jeanne M; Metiu, Anca; Jett, Quintus R (2008). "Perceived Proximity in Virtual Work: Explaining the Paradox of Far-but-Close". Organization Studies 29 (7): 979–1002. doi:10.1177/0170840607083105.

- ↑ Monge, Peter R; Kirste, Kenneth K (1980). "Measuring Proximity in Human Organization". Social Psychology Quarterly 43 (1): 110–115. doi:10.2307/3033753.

- ↑ Monge, Peter R; Rothman, Lynda White; Eisenberg, Eric M; Miller, Katherine I; Kirste, Kenneth K (1985). "The Dynamics of Organizational Proximity". Management Science 31 (9): 1129–1141. doi:10.1287/mnsc.31.9.1129.

- ↑ Olson, Gary M; Olson, Judith S (2000). "Distance Matters". Human Computer Interaction 15: 139–178. doi:10.1207/s15327051hci1523_4.

- ↑ Zajonc, R.B. (1968). "Attitudinal Effect of Mere Exposure". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 9: 2–17. doi:10.1037/h0025848.

- ↑ Hinds, Pamela; Kiesler, Sara (2002). Distributed Work. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ↑ Levitt, B; J.G. March (1988). "Organizational Learning". Annual Review of Sociology 14: 319–340. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.14.1.319.

- ↑ Nelson, R. R. (1982). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- ↑ "Cinematography – Proxemics". Film and Media Studies in ESF. South Island School. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ "Mise en scene" (PDF). Film Studies. University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ "Shot and Camera Proxemics". The Fifteen Points of Mise-en-scene. College of DuPage. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ "Cinematography Part II: MISE-EN-SCENE: Orchestrating the Frame". California State University San Marcos. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ Giannetti, Louis (1990). Understanding Movies, 5th edition. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. p. 64. ISBN 0-13-945585-X.

- ↑ Roud, Richard (28 December 1977). "The Baggy-Trousered Philanthropist". The Guardian: 3.

- ↑ "JudgePhilosophies - Struth, Matt". judgephilosophies.wikispaces.com. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

Further reading

- T. Matthew Ciolek (September 1983). "The Proxemics Lexicon: a first approximation". Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 8 (1): 55–75. doi:10.1007/BF00986330.

- Edward T. Hall (1963). "A System for the Notation of Proxemic Behaviour". American Anthropologist 65 (5): 1003–1026. doi:10.1525/aa.1963.65.5.02a00020.

- Robert Sommer (May 1967). "Sociofugal Space". The American Journal of Sociology 72 (6): 654–660. doi:10.1086/224402.

- Lawson, Bryan (2001). "Sociofugal and sociopetal space". The Language of Space. Architectural Press. pp. 140–144. ISBN 0-7506-5246-2.