Prison literature

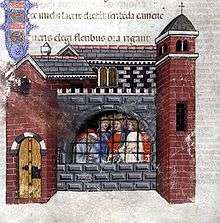

Prison literature is a literary genre characterized by literature that is written while the author is confined in a location against his will, such as a prison, jail or house arrest.[1] The literature can be about prison, informed by it, or simply coincidentally written while in prison. It could be a memoir, nonfiction, or fiction.

History

Some notable historical examples of prison literature include Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy (524 AD) which has been described as “by far the most interesting example of prison literature the world has ever seen.”[2] Hugo Grotius wrote his Commentaries while in prison. Marco Polo found time and inspiration to write his travels to China only after his return and being imprisoned in Genoa.[1] Miguel de Cervantes was held captive as a galley slave between 1575–80 and from this he drew inspiration for his novel Don Quixote (1605). Sir Walter Raleigh compiled his History of the World, Volume 1 in a prison chamber in the Tower of London, but he was only able to complete Volume 1 before he was executed. Raimondo Montecuccoli wrote his aphorisms on the art of war in a Stettin prison (ca 1639-1641).[3] John Bunyan wrote The Pilgrim's Progress (1678) while in jail. Martin Luther translated the New Testament into German while held at Wartburg Castle. Marquis de Sade wrote prolifically during an 11-year period in the Bastille, churning out 11 novels, 16 novellas, 2 volumes of essays, a diary and 20 plays.[1][4]

Napoleon Bonaparte dictated his memoir while imprisoned on St. Helena island; it would become of the best sellers of the 19th century.[1] Fyodor Dostoevsky spent four years of hard labor in a Siberian prison camp for his membership in a liberal intellectual group; the experience changed his outlook and writing style, he began to argue against the Nihilist and Socialist viewpoints, instead championing humility and suffering, and his writing became darker and more complex.[4] Oscar Wilde wrote the philosophical essay "De Profundis" while in Reading Gaol on charges of "unnatural acts" and "gross indecency" with other men.[4]

E. E. Cummings 1922 autobiographical novel The Enormous Room was written while imprisoned by the French during WWI on the charges of expressing anti-war sentiments in private letters home.[4] Adolf Hitler wrote his autobiographical and political ideology book Mein Kampf while he was imprisoned after the Beer Hall Putsch in November 1923. The Italian Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci wrote much of his work while imprisoned by the fascist government of Mussolini during the 1930s; this was later published as Prison Notebooks, and contained his influential theory of cultural hegemony. In 1942 Jean Genet wrote his first novel Our Lady of the Flowers while in prison near Paris, scrawled on scraps of paper.[1][4] O. Henry (William Sidney Porter) wrote 14 stories while in prison for embezzlement, and it was during this time that his pseudonym “O. Henry” began to stick.[4] Nigerian author Ken Saro-Wiwa was executed while in prison, and wrote Sozaboy, about a young naïve imprisoned soldier. Iranian author Mahmoud Dowlatabadi wrote the 500 page Missing Soluch while imprisoned without pen or paper, entirely in his head, then copied it down within 70 days after his release.[5]

A number of postcolonial texts are based on the author's experiences in prison. Nigerian author Chris Abani’s book of poetry Kalakuta Republic is based on his experiences in prison. Pramoedya Ananta Toer wrote the Buru Quartet while in prison in Indonesia. Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o's prison diary titled Detained: A Prisoner's Diary was published in 1981.

Some examples of female prison writers include Madame Roland (Paris, 1793), Krystyna Wituska (Berlin, 1942-44), Nawal El Saadawi (Egypt, 1981), Joan Henry (England, 1951), Caesarina Kona Makhoere (South Africa, 1976-82), Vera Figner (Russia, 1883-1904), Beatrice Saubin (Malaysia, 1890-90), Precious Bedell (New York, 1980-99) and Lady Constance Lytton (England, 1910).

American prison literature

20th century America brought about many pieces of prison literature. Some examples of such pieces are “My Life in Prison” by Donald Lowrie, “Cell Mates” by Agnes Smedley, “Crime and Criminals” by Kate Richards O'Hare, “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” by Malcolm X, “Sing Soft, Sing Loud” by Patricia McConnel, and “AIDS: The View from a Prison Cell” by Dannie Martin. Some other 20th century prison writers include Jim Tully, Ernest Booth, Chester Himes, Nelson Agren, Robert Lowell, George Jackson, Jimmy Santiago Baca, and Kathy Boudin.

At the start of the 21st century, the United States had an incarceration rate of two million people, taking the lead with the highest imprisonment rate worldwide.

Prison literature written in America is of particular interest to some scholars who point out that pieces which reveal the brutality of life behind bars pose an interesting question about American society: “Can these things really happen in prosperous, freedom-loving America?”[6] Since America is globally reputed as being a “democratic haven” and the “land of freedom,” writings that come out of American prisons can potentially present a challenge to everything the nation was founded on. Jack London, a famous American writer who was incarcerated for thirty days in the Erie County Penitentiary, is an example of such a challenger; in his memoir “’Pinched’: A Prison Experience” he recalls how he was automatically sentenced to thirty days in prison with no chance to defend himself or even plead innocent or guilty. While sitting in the courtroom he thought to himself, “Behind me were the many generations of my American ancestry. One of the kinds of liberty those ancestors of mine fought and died for was the right of trial by jury. This was my heritage, stained sacred by their blood…” London’s “sacred heritage” made no difference, however. It is stories such as London’s that make American prison literature a common and popular subtopic of the broader genre of literature.

For readers of American prison memoirs, it means getting a glimpse into a world they would never otherwise experience. As Tom Wicker puts it, “They disclose the nasty, brutish details of the life within – a life the authorities would rather we not know about, a life so far from conventional existence that the accounts of those who experience it exert the fascination of the unknown, sometimes the unbelievable.” He also notes that “what happens inside the walls inevitably reflects the society outside.”[7] So not only do readers acquire a sense of the world inside the walls, gaining insight into the thoughts and feelings of prisoners; they also gain a clearer vision of the society which exists outside the prison walls and how it treats and affects those whom they place within. Tom Wicker described prison literature as a "fascinating glimmer of humanity persisting in circumstances that conspire, with overwhelming force, to obliterate it."[7]

American women's prison literature

In recent years, the population of women in U.S. prisons has increased more quickly than that of men. Women represent almost 10 percent of the U.S. prison population and have limited protection against rape and other sexual violence; many are discriminated against and treated as “sub-human."[8] The works of literature these women write are testament not only to the power of women to overcome the oppression and discrimination they face in their daily lives, but the strength to withstand the defiling experience of prison life and use self-expression as a means of emotional escape and freedom.

Over two-thirds of women prisoners in local, state, and federal institutions in the United States are "women of color," the majority being African American women. Studies have shown that in general, African American women, more so than their Caucasian counterparts, come from impoverished backgrounds and have poor personal health.[9] African American women are also said to be part of a "culture of struggle and resistance."[10] Many believe that these distinctions make this genre worthy of special study within the broader genre of women's prison literature.

See also

- Category:Prison writings

- Category:Memoirs of imprisonment

- Prison blogs

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tony Perrottet. "Serving the Sentence", New York Times Book Review, July 24, 2011.

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia . The quote is commonly seen in a number of sources, but without attribution; the Catholic Encyclopedia article is the oldest “known” citation found.

- ↑ My unrelenting vice, Bora Cosic, sightandsight.com, Sept. 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Emily Temple. "In Black and White: 10 Famed Literary Jailbirds", Flavorwire, Jan 15, 2012.

- ↑ Interview with Mahmoud Dowlatabadi

- ↑ H. Bruce Franklin, ed., Prison Writing in 20th Century America (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1998)

- 1 2 Tom Wicker, “Foreword,” in Prose and Cons: Essays on Prison Literature in the United States, ed. D. Quentin Miller (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005), 280.

- ↑ Tracy Huling, “Foreword,” in Wall Tappings, ed. Judith A. Scheffler, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2002)

- ↑ Paula C. Johnson, Inner Lives: Voices of African American Women in Prison (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2003).

- ↑ Darlene Clark Hine, “The Faces of Our Past: Images of Black Women from Colonial Times to the Present,” in Inner Lives, ed. Paula C. Johnson (New York: New York University Press, 2003).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|