Principality of Lower Pannonia

| Principality of Lower Pannonia | |||||

| |||||

Principality of Lower Pannonia under Koceľ | |||||

| Capital | Mosapurc/Urbs Paludarum/Blatengrad | ||||

| Government | principality | ||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||

| • | Established | 846 | |||

| • | Disestablished | 875 | |||

| Today part of | Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Austria | ||||

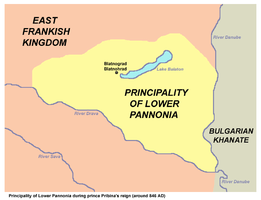

The Principality of Lower Pannonia[1] or Balaton Principality[2] was a Slavic principality, vassal to the Frankish Empire,[2][3] or according to others[4] a comitatus of the Frankish Empire, led initially by a dux (Pribina) and later by a comes (Pribina's son, Kocel). It was one of the early Slavic polities (Kocel's title was "Comes de Sclauis" - Count of the Slavs) [5] and was situated mostly in Transdanubia region of modern Hungary, but also included parts of modern Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia and Austria. Its capital was Mosapurc "Mosapurc regia civitate",[1] present-day Zalavár (in Old-Slavonic Blatengrad, in Latin Urbs Paludarum).

Background

.jpg)

The Slavic settlement of Pannonia started in the late 5th century after the fall of the Hunnic tribal union. In the late 6th century the Slavs in the territory became subjects of the Avar tribal union (Avar Khaganate). Trouble by internal conflicts as well as external attacks by Frankish Empire (led by Charles the Great) and Bulgarian Khanate (led by Khan Krum), the Avar polity collapsed by the early 9th century. Initially, Lower Pannonia lay between the Drava, Danube and Sava rivers, whilst Upper Pannonia lay north of the Drava river. Collectively, the southeastern Slavic marches of the Carolongian empire were called the Eastland (Plaga Orientalis). During the first two decades of the ninth century, Lower Pannonia was ruled by Slavic Prince Ljudevit Posavski, a Frankish vassal. After his rebellion, Louis removed the lands from the Friuliun Duke and placed them under his son's (Louis the German) Bavarian sub-kingdom and the river Raab became the new border between Upper and Lower Pannonia, with the core and the name of Lower Pannonia moving north of the river Drava. The turmoils did not end, as in 827, the Bulgarians invaded much of Lower Pannonia, but were then pushed back by Louis the German the following year.

The Principality of Lower Pannonia

In the course of the creation of Great Moravia in 833 to the north of the Danube, Pribina (Priwina), until then the Prince of the Principality of Nitra, was expelled from his country by Mojmír I of the Moravian principality. After several adventures, he was eventually given the Frankish lands in Lower Pannonia in 846 AD, where he founded the Lower Pannonia Principality (whose Slavic name "Blatno" means "Principality (Duchy) of the Muddy lake (or river)"). This was a calculated move on the part of Louis the German, who aimed to curtail the power of his Prefect, Ratbod, as well as gain an ally (and buffer) against the potential threats of Great Moravia and Bulgaria. Pribina's capital was Blatnograd (Blatnohrad, later called Mosapurc), a city built at the Zala river (Zala in Hungarian, in Slavic languages "Blatna" or similar forms meaning Muddy river), near Keszthely, between the small and large Balaton lakes (Balaton in Hungarian, in Slavic languages Blatno / Blatenské jazero or similar forms meaning Muddy lake). He greatly fortified this city, and surrounded by swamps and dense forests, it lay in a strategically powerful position. Pribina was Louis the German's Dux. His state grew powerful and Pribina ruled for two decades. His state contained a retinue of followers, including Carantanians, Franks and even Slavonized Avars. Pribina allowed the Archbishop of Salzburg to consecrate churches in the area.

After an attack by Carloman (during his rebellion against Louis the German), Pribina's son, Kotsel (Gozil, Koceľ, Kocelj, 861-876), fled to the court of Louis. He was soon re-instated in his father's lands. In the summer of 867, Prince Kocel provided short-term hospitality to brothers Cyril and Methodius on their way from Great Moravia to the pope in Rome to justify the use of the Slavonic language as a liturgical language. They and their disciples turned Blatnograd into one of the centers that spread the knowledge of the new Slavonic script (Glagolitic alphabet) and literature, educating numerous future missionaries in their native language.

Although a Frankish vassal, it later started resisting the influence of German feudal lords and clergy, trying to organize an independent Slavic archdiocese. Eventually, after Kocel's death in 876, Lower Pannonia was again made a direct part of the East Frankish Empire, ruled by Arnulf of Carinthia. During the succession strife in East Frankia, in 884, the area was conquered by Great Moravia, c. 894. After a few years of peace, Arnulf renewed his wars with Moravia, and recaptured Lower Pannonia. After he claimed the Imperial Crown in 896, Arnulf gave Lower Pannonia to another Slavic duke, Braslav, as a fiefdom. Soon afterwards, in 901 it was conquered by the Hungarians, who became the new ruling core, but retained many elements of Slavic political organization. The territory became part of the arising Hungarian state.

|

|

| Southeastern Europe, latter half of 9th century. The principality (Pannonian Duchy) was created out of land granted from Frankish eastern marches | State of Braslav |

Parts of the principality

Pribina's authority stretched from the Rába river to the north, to Pécs to the southeast, and to Ptuj to the West.[5] Temporary, it also included territory in the east of the Danube [6] and in the south of the Drava,[6][7] i.e. parts of present-day central Hungary (between Danube and Tisa), northern Serbia (Bačka, west Syrmia) and eastern Croatia (west Syrmia, east Slavonia).

Rulers

See also

- List of early East Slavic states

- Principality of Nitra

- Principality of Pannonian Croatia

- East Francia

- Great Moravia

- Principality of Hungary

Sources

- Kirilo-Metodievska entsiklopedia (Cyrillo-Methodian Encyclopedia), in 3 volumes, (in Bulgarian), [DR5.K575 1985 RR2S], Sofia 1985

- Welkya - Creation of Slavic Script, .

- Dejiny Slovenska (History of Slovakia) in 6 volumes, Bratislava (volume 1 1986)

- Steinhübel, Ján: Nitrianske kniežatstvo (Principality of Nitra), Bratislava 2004

Notes

- 1 2 Charles R. Bowlus, Franks, Moravians, and Magyars: the struggle for the Middle Danube, 788-907, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995, pp. 204-220

- 1 2 Július Bartl, Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2002, pp. 19-20

- ↑ Anton Špiesz, Duśan Čaplovič, Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2006, p. 20

- ↑ Béla Miklós Szőke, New findings of the excavations in Mosaburg /Zalavár (Western Hungary), In: Joachim Henning (editor), Post-Roman towns, Trade and Settlement in Europe and Byzantinum Vol.1,(The Heirs of the Roman west) , Walter de Gruyter, 2007, p. 411

- 1 2 Oto Luthar, The Land Between: A History of Slovenia, Peter Lang, 2008, p. 105

- 1 2 Dragan Brujić, Vodič kroz svet Vizantije - od Konstantina do pada Carigrada, drugo izdanje, Beograd, 2005.

- ↑ Grad Vukovar - Povijest

External links

- Map - Principality of Lower Pannonia during the reign of Koceľ

- Map - Principality of Lower Pannonia during the reign of Koceľ