Premature rupture of membranes

| Premature rupture of membranes | |

|---|---|

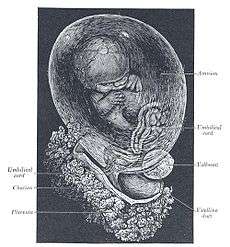

A fetus surrounded by the amniotic sac which is enclosed by fetal membranes. In PROM, these membranes rupture before labor starts. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | obstetrics |

| ICD-10 | O42 |

| ICD-9-CM | 658.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 10600 |

| eMedicine | med/3246 |

| MeSH | D005322 |

Premature rupture of membranes (PROM), or pre-labor rupture of membranes, is a condition that can occur in pregnancy. It is defined as rupture of membranes (breakage of the amniotic sac), commonly called breaking of the mother's water(s),[1] more than 1 hour before the onset of labor.[2] The sac (consisting of 2 membranes, the chorion and amnion) contains amniotic fluid, which surrounds and protects the fetus in the uterus (womb). After rupture, the amniotic fluid leaks out of the uterus through the vagina.

Women with PROM usually experience a painless gush of fluid leaking out from the vagina, but sometimes a slow steady leakage occurs instead.

When premature rupture of membranes occurs at or after 37 weeks completed gestational age (at term), there is minimal risk to the fetus and labor typically starts soon after.

If rupture occurs before 37 weeks, called preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), the fetus and mother are at greater risk for complications. PPROM causes one-third of all preterm births,[3] and babies born preterm (before 37 weeks) can suffer from the complications of prematurity, including death. Open membranes provide a path for bacteria to enter the womb and puts both the mother and fetus at risk for life-threatening infection. Low levels of fluid around the fetus also increase the risk of the umbilical cord compression and can interfere with lung and body formation in early pregnancy.[3]

Women who experience premature rupture of membranes should be evaluated promptly in the hospital to determine if a rupture of membranes has indeed occurred, and to be treated appropriately to avoid infection and other complications.

Classification

- Premature rupture of membranes (PROM): when the fetal membranes rupture early, at least one hour before labor has started.[4]

- Prolonged PROM: a case of premature rupture of membranes in which more than 24 hours has passed between the rupture and the onset of labor.[5]

- Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes (PPROM): premature rupture of membranes that occurs before 37 weeks.

- Midtrimester PPROM or Pre-viable PPROM: premature rupture of membranes that occurs before 24 weeks completed gestational age of the fetus. Before this age, the fetus cannot survive outside of the mother's womb.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Most women will experience a painless gush of fluid that leaks out of the vagina. Sometimes women notice a steady leakage of small amounts of watery fluid rather than a distinct "gush".[4] Other symptoms include a change in color and consistency of fluid coming out of the vagina, flecks of meconium (fetal stool) in the fluid, or a decrease in the size of the uterus.[5]

Risk factors

The cause of premature rupture of membranes (PROM) is not clearly understood, but the following are risk factors that have been shown to increase the chance of it happening. In many cases, however, no risk factor is identified.[7]

- Infections: urinary tract infection, sexually transmitted diseases, lower genital infections (ex: Bacterial Vaginosis)[4]

- Cigarette smoking during pregnancy[7]

- Illicit drug use during pregnancy[2]

- Having had PROM or preterm delivery in previous pregnancies[4]

- Hydramnios: too much amniotic fluid [5]

- Multiple gestation: being pregnant with two or more fetuses at one time[4]

- Having had episodes of bleeding anytime during the pregnancy[4]

- Invasive procedures (ex: amniocentesis)[5]

- Nutritional deficits [7]

- Cervical insufficiency: having a short or prematurely dilated cervix during pregnancy [5]

- Low socioeconomic status[7]

- Being underweight[7]

Pathophysiology

Weakened fetal membranes

Fetal membranes likely break because they become weak and fragile. This weakening is a normal process that typically happens at term as the body prepares for labor and delivery. But, this can be a problem when it occurs pre-term (before 37 weeks). The natural weakening of fetal membranes is thought to be due to one or a combination of the following. In premature rupture of membranes, these processes are activated too early:

- Cell death: when cells undergo programed cell death, they release chemical markers that are detected in higher concentrations in cases of PPROM.

- Poor assembly of collagen: collagen is a molecule that gives fetal membranes their strength. In cases of PPROM, proteins that bind and cross-link collagen to increase its tensile strength are altered.

- Breakdown of collagen: collagen is broken down by enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are found at higher levels in PPROM amniotic fluid. Matrix metalloproteinases are inhibited by tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs) which are found at lower levels in PPROM amniotic fluid.[7]

Infection

Infection and inflammation likely explains why membranes break earlier than they are supposed to. In studies, bacteria have been found in the amniotic fluid from about one-third of cases of PROM. Often, testing of the amniotic fluid is normal, but a subclinical infection (too small to detect) or infection of maternal tissues next to the amniotic fluid, may still be contributing. In response to infection, the body creates inflammation by making chemicals (ex: cytokines) that weaken the fetal membranes and put them at risk for rupture.[7] Premature rupture of membranes is also a risk factor in the development of neonatal infection.

Genetics

Many genes play a role in inflammation and collagen production, therefore inherited genes may play a role in predisposing a person to PROM.[7]

Diagnosis

To know for sure if a woman has experienced premature rupture of membranes (PROM), a health care clinician must prove that (1) the fluid leaking from the vagina is amniotic fluid, and (2) that labor has not yet started. To do this, a health care clinician will take a medical history, do a gynecological exam using a sterile speculum, and ultrasound.[5]

- History: a person with PROM typically recalls a sudden gush of fluid loss from the vagina, or steady loss of small amounts of fluid.[5]

- Sterile speculum exam: a health care clinician will insert a sterile speculum into the vagina in order to see inside and perform the following evaluations. Digital cervical exams, in which gloved fingers are inserted into the vagina to measure the cervix, are avoided until the women is in active labor to reduce the risk of infection.[6]

- Pooling test: Pooling is when a collection of amniotic fluid can be seen in the back of the vagina (vaginal fornix). Sometimes leakage of fluid from the cervical opening can be seen when the person coughs or does a valsalva maneuver.[5]

- Nitrazine test: A sterile cotton swab is used to collect fluid from the vagina and place it on nitrazine (phenaphthazine) paper. Amniotic fluid is mildly basic (pH 7.1 - 7.3) compared to normal vaginal secretions which are acidic (pH 4.5 - 6).[7] Basic fluid, like amniotic fluid, will turn the nitrazine paper from orange to dark blue.[5]

- Ferning test: A sterile cotton swab is used to collect fluid from the vagina and place it on a microscope slide. After drying, amniotic fluid will form a crystallization pattern called arborization[2] which resembles leaves of a fern plant when viewed under a microscope.[4]

Extra tests

The following tests should only be used if the diagnosis is still unclear after the standard tests above.

- Ultrasound: Ultrasound can measure the amount of fluid still in the uterus surrounding the fetus. If the fluid levels are low, PROM is more likely.[4] This is helpful in cases when the diagnosis is not certain, but is not, by itself, definitive.[2]

- Immune-chromatological tests (AmniSure, Actim PROM test): These are commercially available test kits that detect chemicals present in amniotic fluid: placental alpha microglobulin-1 (AmniSure) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (Atim PROM test). These are helpful if negative to rule-out PROM, but are not that helpful if positive because the false-positive rate is 19-30%.[2]

- Indigo carmine dye test: In this test, a needle is used to inject indigo carmine dye (blue) into the amniotic fluid that remains in the uterus through the abdominal wall. In the case of PROM, blue dye can be seen on a stained tampon or pad after about 15–30 minutes.[5] This method can be used to definitively make a diagnosis, but is rarely done because it is invasive and increases risk of infection. But, can be helpful if the diagnosis is still unclear after the above evaluations have been done.[5]

It is unclear if different methods of assessing the fetus in a woman with PPROM affects outcomes.[8]

False positives

Like amniotic fluid, blood, semen, vaginal infections,[5] antiseptics,[7] basic urine, and cervical mucus [4] also have a basic pH and can also turn nitrazine paper blue.[5] Cervical mucus can also make a pattern similar to ferning on a microscope slide, but it is usually patchy [5] and with less branching.[4]

Differential diagnosis

Other things to keep in mind that may present similarly to premature rupture of membranes are the following:[4]

- Urinary incontinence: leakage of small amounts of urine is common in the last part of pregnancy

- Normal vaginal secretions of pregnancy

- Increased sweat or moisture around the perineum

- Increased cervical discharge: this can happen when there is a genital tract infection

- Semen

- Douching

- Vesicovaginal fistula: an abnormal connection between the bladder and the vagina

- Loss of the mucus plug

Prevention

Women who have had premature rupture of membranes (PROM) are more likely to experience it in future pregnancies.[2] There is not enough data to recommend a way to specifically prevent future PROM. However, any woman that has had a history of preterm delivery, because of PROM or not, is recommended to take progesterone supplementation to prevent preterm birth recurrence.[2][5]

Management

|

Fetal age |

Management | |

|---|---|---|

|

Term |

> 37 weeks |

|

|

Late Pre-term |

34–36 weeks |

|

|

Preterm |

24–33 weeks |

|

|

Pre-viable |

< 24 weeks |

|

The management of PROM remains controversial, and depends largely on the gestational age of the fetus and other complicating factors. The risks of quick delivery (induction of labor) vs. watchful waiting in each case is carefully considered before deciding on a course of action.[2]

In all patients with PROM, the age of the fetus, its position in the uterus, and its wellbeing should be evaluated. This can be done with ultrasound, electronic fetal heart rate monitoring, and uterine activity monitoring. This will also show whether or not uterine contractions are happening which may be a sign that labor is starting. Signs and symptoms of infection should be closely monitored, and, if not already done, a group B streptococcus (GBS) culture should be collected.

At any age, if the fetal well-being appears to be compromised, or if intrauterine infection is suspected, the baby should be delivered quickly by artificially stimulating labor (induction of labor).[2][6]

PROM at term

Both expectant management (watchful waiting) and an induction of labor (artificially stimulating labor) are considered in this case. 90% of women start labor on their own within 24 hours, and therefore it is reasonable to wait for 12–24 hours as long as there is no risk of infection.[6] However, if labor does not begin soon after the rupture of membranes, an induction of labor is recommended because it reduces rates of infections, decreases the chances that the baby will require a stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and does not increase the rate of cesarean sections.[2] If a woman strongly does not want to be induced, watchful waiting is an acceptable option as long as there is no sign of infection, the fetus is not in distress, and she is aware and accepts the risks of prolonged PROM.[2] There is not enough data to show that the use of prophylactic antibiotics (to prevent infection) is beneficial for mothers or babies at or near term. Because of the potential side effects and development of antibiotic resistance, the use of antibiotics without the presence of infection is not recommended in this case.[9]

PPROM greater than 34 weeks

When the fetus is premature (< 37 weeks), the risk of being born prematurely must be weighed against the risk of prolonged membrane rupture. As long as the fetus is 34 weeks or greater, delivery is recommended as if the baby was term (see above).[2]

PPROM less than 34 weeks

Before 34 weeks, the fetus is at a much higher risk of the complications of prematurity. Therefore, as long as the fetus is doing well, and there is no signs of infection or placental abruption, watchful waiting (expectant management) is recommended.[2] The younger the fetus, the longer it takes for labor to start on its own,[5] but most women will deliver within a week.[7] Waiting usually requires a woman to stay in the hospital so that health care providers can watch her carefully for infection, placental abruption, umbilical cord compression, or any other fetal emergency that would require quick delivery by induction of labor.[2]

Recommended

- Monitoring for infection: signs of infection include a fever in the mother, fetal tachycardia (fast heart rate of the fetus, > 160 beats per minute), or tachycardia in the mother (> 100 beats per minute). White blood cell (WBC) counts are not helpful in this case because WBC's are normally high in late pregnancy.[2]

- Steroids before birth: corticosteroids (betamethasone) given to the mother of a baby at risk of being born prematurely can speed up fetal lung development and reduce the risk of death of the infant, respiratory distress syndrome, brain bleeds, and bowel death.[2] It is recommended that mothers receive one course of corticosteroids between 24 and 34 weeks when there is a risk of preterm delivery. In cases of PPROM these medications do not increase the risk of infection even though steroids are known to suppress the immune system. More than two courses is not recommended because three or more can lead to small birth weight and small head circumference.[2] In pregnancies between 32 and 34 weeks (right around the time that fetal lungs mature) vaginal fluid can be tested to determine fetal lung maturity using chemical markers which can help to decide if corticosteroids should be given.[5]

- Magnesium sulfate: Intravenous magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) is given to the mother in cases when there is a risk of preterm birth before 32 weeks. This has been shown to protect the fetal brain and reduce the risk of cerebral palsy.[2]

- Latency Antibiotics: As expected, antibiotics given to mothers that experience PPROM protect against infections. Additionally, antibiotics increase the time that babies stay in the womb. Antibiotics don't seem to prevent death or make a difference in the long-term (years after the baby is born). But, because of the short-term benefits, routine use of antibiotics in PPROM is still recommended.[10] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends a seven-day course of intravenous ampicillin and erythromycin followed by oral amoxicillin and erythromycin if watchful waiting is attempted before 34 weeks.[2] Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid increases the risk of fetal bowel death (necrotizing enterocolitis) and should be avoided in pregnancy.[2]

- Prophylactic Antibiotics: If a woman is colonized with group B strep, than the typical use of antibiotics during labor is recommended to prevent transmission of this bacteria to the fetus, regardless of earlier treatments.[2]

Controversial or not recommended

- Preventative tocolysis (medications to prevent contractions): the use of tocolytic medications to prevent labor contractions is controversial. On the one hand, this can delay delivery and allow the fetus more time to develop and benefit from antenatal corticosteroid medication, on the other hand it increases the risk of infection/chorioamnionitis. The use of tocolysis has not shown to benefit mom or baby and currently there is not enough data to recommend or discourage its use in the case of preterm PROM.[2][3]

- Therapeutic tocolysis (medications to stop contractions): Once labor has started, using tocolysis to stop labor has not been shown to help, and is not recommended.[2]

- Amnioinfusion: This treatment attempts to replace the lost amniotic fluid from the uterus by infusing normal saline fluid into the uterine cavity. This can be done through the vagina and cervix (transcervical amnioinfusion) or by passing a needle through the abdominal wall (transabdominal amnioinfusion). Current data suggests that this treatment prevents infection, lung problems, and fetal death. However, there have not been enough trials to recommend its routine use in all cases of PPROM.[11]

- Home care: Typically women with PPROM are managed in the hospital, but, occasionally they opt to go home if watchful waiting is attempted. Since labor usually starts soon after PPROM, and infection, umbilical cord compression, and other fetal emergencies can happen very suddenly, it is recommended that women stay in the hospital in cases of PPROM after 24 weeks.[2] Currently, there is not enough evidence to determine meaningful differences in safety, cost, and women's views between management at home vs. the hospital.[12]

Pre-viable PPROM

Before 24 weeks, a fetus is not viable meaning it cannot live outside the mother. In this case, either watchful waiting at home or an induction of labor done.[2]

- Watchful waiting (expectant management): Waiting is reasonable as long as there is no evidence of infection. Because the risk of infection is so high, the mother should check her temperature often and return to the hospital if she develops any signs or symptoms of infection, labor, or vaginal bleeding. These women are typically admitted to the hospital once their fetus reaches 24 weeks and then managed the same as women with PPROM before 34 weeks (discussed above). Antenatal corticosteroids, latency antibiotics, magnesium sulfate, and tocolytic medications are not recommended until the fetus reaches viability (24 weeks).[2] In cases of pre-viable PPROM, chance of survival of the fetus is between 15-50%, and the risk of chorioamnionitis is about 30%.[5]

- Induction of labor/termination: Because of the high risk of extreme fetal prematurity, severe disability, long NICU stays, and likely fetal death, women who experienced pre-viable PROM often choose to undergo an induction of labor to end the pregnancy.

Chorioamnionitis

Chorioamnionitis is a bacterial infection of the fetal membranes, which can be life-threatening to both mother and fetus. Women with PROM at any age are at high risk of infection because the membranes are open and allow bacteria to enter. Women are checked often (usually every 4 hours) for signs of infection: fever ( > 38 °C/100.5 °F), uterine pain, fast maternal heart rate (>100 beats per minute), fast fetal heart rate (>160 beats per minute), or foul smelling amniotic fluid.[7] Elevated white blood cells are not a good way to predict infection because they are normally high in labor.[5] If infection is suspected, artificial induction of labor is started at any gestational age and broad antibiotics are given. Cesarean section should not be automatically done in cases of infection, and should only be reserved for the usual fetal emergencies.[5]

Outcomes

The consequences of PROM depend on the gestational age of the fetus.[4] When PROM occurs at term (after 37 weeks), it is typically followed soon thereafter by the start of labor and delivery. About half of women will give birth within 5 hours, and 95% will give birth within 28 hours without any intervention.[2] The younger the fetus, the longer the latency period (time between membrane rupture and start of labor). Rarely, in cases of preterm PROM, amniotic fluid will stop leaking and the amniotic fluid volume will return to normal.[2]

Infection (any age)

At any gestational age, an opening in the fetal membranes provides a route for bacteria to enter the womb. This can lead to chorioamnionitis (an infection of the fetal membranes and amniotic fluid) which can be life-threatening to both the mother and fetus.[4] The risk of infection increases the longer the membranes remain open and baby undelivered.[2] Women with preterm PROM will develop an intramniotic infection 15-25% of the time, and the chances of infection increase at earlier gestational ages.[2]

Pre-term birth (before 37 weeks)

PROM occurring before 37 weeks (PPROM) is one of the leading causes of preterm birth. 30-35% of all preterm births are caused by PPROM.[7] This puts the fetus at risk for the many complications associated with prematurity such as respiratory distress, brain bleeds, infection, necrotizing enterocolitis (death of the fetal bowels), brain injury, muscle dysfunction, and death.[4] Prematurity from any cause leads to 75% of perinatal mortality and about 50% of all long-term morbidity.[13] PROM is responsible for 20% of all fetal deaths between 24 and 34 weeks gestation.[7]

Fetal development (before 24 weeks)

Before 24 weeks the fetus is still developing its organs, and the amniotic fluid is important for protecting the fetus against infection, physical impact, and for preventing the umbilical cord from becoming compressed. It also allows for fetal movement and breathing that is necessary for the development of the lungs, chest, and bones.[4] Low levels of amniotic fluid due to mid-trimester or previable PPROM (before 24 weeks) can result in fetal deformity (ex: Potter-like facies), limb contractures, pulmonary hypoplasia (underdeveloped lungs),[2] infection (especially if the mother is colonized by group B streptococcus or bacterial vaginosis), prolapsed umbilical cord or compression, and placental abruption.[5]

PROM after second-trimester amniocentesis

Most cases of PROM occur spontaneously, but the risk of PROM in women undergoing a second trimester amniocentesis for prenatal diagnosis of genetic disorders is 1%. Although, no studies are known to account for all cases of PROM that stem from amniocentesis. This case, the chances of the membranes healing on their own and the amniotic fluid returning to normal levels is much higher than spontaneous PROM. Compared to spontaneous PROM, about 70% of women will have normal amniotic fluid levels within one month, and about 90% of babies will survive.[2]

Epidemiology

PROM occurs in about 10-12% of all births in the United States.[2][4][5] Of all term pregnancies (> 37 weeks) about 8% are complicated by PROM,[7] 20% of these become prolonged PROM.[5] About 30% of all preterm deliveries (before 37 weeks) are complicated by PPROM, and rupture of membranes before viability (before 24 weeks) occurs in less than 1% of all pregnancies.[2] Since there are significantly fewer preterm deliveries than term deliveries, the number of PPROM cases make up only about 5% of all cases of PROM.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Water breaking, Mayo Clinic

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 "Practice Bulletins No. 139". Obstetrics & Gynecology 122 (4): 918–930. October 2013. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000435415.21944.8f. PMID 24084566. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 Mackeen, AD; Seibel-Seamon, J; Muhammad, J; Baxter, JK; Berghella, V (27 February 2014). "Tocolytics for preterm premature rupture of membranes.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2: CD007062. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007062.pub3. PMID 24578236.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Beckmann, Charles (2010). Obstetrics and Gynecology, 6e. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. Chapter 22: Premature Rupture of Membranes, pg 213–216. ISBN 978-0781788076.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 DeCherney, Alan (2013). Current Diagnosis & Treatment : Obstetrics & Gynecology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. Chapter 14: Late Pregnancy Complication, section: premature rupture of membranes. ISBN 978-0071638562.

- 1 2 3 4 Beckmann, Charles (2014). Obstetrics and Gynecology, 7e. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. Chapter 17: Premature Rupture of Membranes, pg 169–173. ISBN 978-1451144314.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Cunningham, F (2014). Williams Obstetrics. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. Chapter 23: Abnormal Labor. ISBN 978-0071798938.

- ↑ Sharp, GC; Stock, SJ; Norman, JE (Oct 3, 2014). "Fetal assessment methods for improving neonatal and maternal outcomes in preterm prelabour rupture of membranes.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 10: CD010209. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010209.pub2. PMID 25279580.

- ↑ Wojcieszek, AM; Stock, OM; Flenady, V (29 October 2014). "Antibiotics for prelabour rupture of membranes at or near term.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 10: CD001807. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001807.pub2. PMID 25352443.

- ↑ Kenyon, S; Boulvain, M; Neilson, JP (2 December 2013). "Antibiotics for preterm rupture of membranes.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 12: CD001058. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001058.pub3. PMID 24297389.

- ↑ Hofmeyr, GJ; Eke, AC; Lawrie, TA (30 March 2014). "Amnioinfusion for third trimester preterm premature rupture of membranes.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 3: CD000942. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000942.pub3. PMID 24683009.

- ↑ Abou El Senoun, G; Dowswell, T; Mousa, HA (14 April 2014). "Planned home versus hospital care for preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes (PPROM) prior to 37 weeks' gestation.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 4: CD008053. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008053.pub3. PMID 24729384.

- ↑ Hösli, Irene (2014). "Tocolysis for preterm labor: expert opinion". Arch Gynecol Obstet 289: 903–9. doi:10.1007/s00404-013-3137-9. PMID 24385286. Retrieved Nov 14, 2015.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||