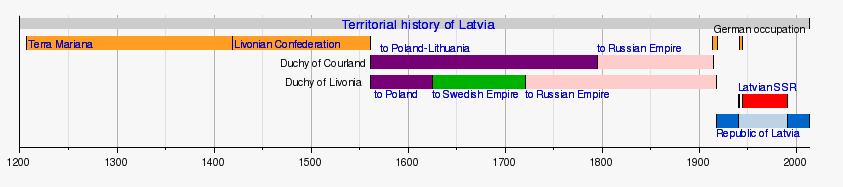

History of Latvia

The History of Latvia began around 9000 BC with the end of the last glacial period in northern Europe. Ancient Baltic peoples appeared during the second millennium BC, and four distinct tribal realms in Latvia's territories were identifiable towards the end of the first millennium AD. Latvia's principal river, the Daugava River, was at the head of an important mainland route from the Baltic region through Russia into southern Europe and the Middle East that was used by the Vikings and later Nordic and German traders.

In the early medieval period, the region's peoples resisted Christianisation and became subject to attack in the Northern Crusades. Today's capital, Riga, founded in 1201 by Teutonic colonists at the mouth of the Daugava, became a strategic base in a papally-sanctioned conquest of the area by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. It was to be the first major city of the southern Baltic and, after 1282, a principal trading centre in the Hanseatic League. By the 16th century, Germanic dominance in the region was increasingly challenged by other powers.

Due to Latvia's strategic location and prosperous city of Riga, its territories were a frequent focal point for conflict and conquest between at least four major powers: the State of the Teutonic Order (later Germany), the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden and Russia. The longest period of external hegemony in the modern period began in 1710, when control over Riga switched from Sweden to Russia during the Great Northern War. Under Russian control, Latvia was in the vanguard of industrialisation and the abolition of serfdom, so that by the end of the 19th century, it had become one of the most developed parts of the Russian Empire. The increasing social problems and rising discontent that this brought meant that Riga also played a leading role in the 1905 Russian Revolution.

A Latvian National Awakening arose in the 1850s and continued to bear fruit after World War I when, after two years of struggle in the Russian Civil War, Latvia finally won sovereign independence, as recognised by Russia in 1920 and by the international community in 1921. Latvia's independent status was interrupted at the outset of World War II in 1940, when the country was forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union, invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany in 1941, then retaken by the Soviets in 1944–45.

From the mid-1940s, the country was subject to Soviet economic control and saw considerable Russification of its peoples. However, Latvian culture and infrastructures survived and, during the period of Soviet liberalisation under Mikhail Gorbachev, Latvia once again took a path towards independence, eventually succeeding in August 1991 to be recognised by Russia the following month. Since then, under restored independence, Latvia has become a member of the United Nations, entered NATO and joined the European Union.

Prehistory

The proto-Baltic forefathers of the Latvian people have lived on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea since the third millennium BCE.[1]

At the beginning of this era, the territory known today as Latvia became famous as a trading crossroads. The renowned "route from the Vikings to the Greeks" mentioned in ancient chronicles stretched from Scandinavia through Latvian territory via the Daugava River to the ancient Kievan Rus' and Byzantine Empire.

The ancient Balts of this time actively participated in the trading network. Across the European continent, Latvia's coast was known in particular as a place for obtaining amber. Up to and into the Middle Ages, amber was more valuable than gold in many places. Latvian amber was known in places as far away as Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, and the Amber Road was intensively used for the transfer of amber to the south of Europe. In the 10th century, the ancient Balts started to form specific tribal realms. Gradually, five individual Baltic tribal cultures developed: Curonians, Livonians, Latgalians, Selonians, Semigallians (Latvian: kurši, līvi, latgaļi, sēļi, zemgaļi). The largest of them was the Latgallian tribe, which was the most advanced in its socio-political development. The main Latgallian principality was Jersika, ruled by Greek Orthodox princes from the Latgallian-Polotsk branch of the Rurik dynasty. The last ruler of Jersika, mentioned in the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia (a document that describes events of the late 12th and early 13th centuries) was prince Visvaldis (Vissewalde, rex de Gercike). When he divided his realm in 1211, part of the country was called "Latvia" (terra, quae Lettia dicitur), probably the first time this name is mentioned in written sources. In contrast, the Couronians maintained a lifestyle of intensive invasions that included looting and pillaging. On the west coast of the Baltic Sea, they became known as the "Baltic Vikings." But Selonians and Semgallians, closely related to Aukštaitians and Samogitians, were known as peace-loving and prosperous farmers. Livonians lived along the shores of the Gulf of Riga and were fishers and traders.

German period (1207–1561)

Latvian territory has frequently been invaded by other larger nations because of its strategic geographic location. This situation has defined the fate of Latvia and its people.

At the end of the 12th century, Latvia was often visited by traders from Western Europe who set out on trading journeys along Latvia's longest river, the Daugava, to Russia. Among them were German traders who came with preachers who attempted to convert the pagan Baltic and Finno-Ugric tribes to the Christian faith. The Livonians did not willingly convert to the new beliefs and practices, and they particularly opposed the ritual of baptism. News of this reached Pope Celestine III in Rome, and it was decided in 1195 that Crusaders would be sent into Latvia to influence the situation.

The Germans founded Riga in 1201, and gradually it became the largest city in the southern part of the Baltic Sea. The Order of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword was founded in 1202 to subjugate the local population. The Livonians were conquered by 1207 and most of the Latgalians by 1214. But the Brothers of the Sword were defeated at the Battle of Saule in 1236, and its remnants accepted incorporation into the Teutonic Order. By the end of the 13th century, the Curonians and Semigallians were also subjugated, and the development of the separate tribal realms of the ancient Latvians came to an end.

In the 13th century, an ecclesiastical state known as Terra Mariana, or Livonia, was established under the Germanic authorities. It consisted of what is now Latvia and Estonia. In 1282, Riga (and later Cēsis, Limbaži, Koknese and Valmiera) were included in the Northern German Trading Organisation, better known as the Hanseatic League (Hansa). From this time, Riga became an important point in west-east trading, and it formed close cultural contacts with Western Europe.

The Reformation reached Livonia in 1521. It was supported in particular in the cities, and by the middle of the 16th century, the majority of the population had already converted to Lutheranism.

In the 15th–16th centuries, the hereditary landed class gradually evolved from vassals of the Order and the bishops. In time, their descendants came to own vast estates over which they exercised absolute rights. At the end of the Middle Ages, this Baltic German minority had established themselves as the governing elite, partly as an urban trading population in the cities, and partly as rural landowners, via a vast manorial network of estates in Latvia. The titled landowners wielded immense economic power; they had a duty to care for the peasants dependent on them, however in practice the latter sank into serfdom.

Lithuanian-Polish and Swedish period (1561–1795)

Livonian War 1558–1583

In September 1557 the Livonian Confederation and the Polish–Lithuanian union signed the Treaty of Pozvol, which created a mutual defensive and offensive alliance. Tsar Ivan the Terrible of Russia regarded this as a provocation, and in January 1558, he reacted with the invasion of Livonia that began the Livonian War of 1558-83. On 2 August 1560, the forces of Ivan the Terrible defeated the united forces of the Livonian Order and the Archibishop of Riga at the Battle of Ērģeme.

The same year, Johannes IV von Münchhausen, the prince-bishop of Ösel-Wiek and Courland, sold his lands to king Frederick II of Denmark for 30,000 thalers. To avoid hereditary partition of his lands, King Frederick II gave that territory to his younger brother Magnus von Lyffland on condition that he renounce his rights to succession in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. In 1560, it seemed that Magnus and his supporters would be able to establish sovereignty in Livonia easily. After all, he had been recognised as sovereign by the Bishop of Ösel-Wiek and Courland and as the prospective ruler of his lands by the authorities of The Bishopric of Dorpat. The Bishopric of Reval with the Harrien-Wierland gentry took his side, and the Livonian Order conditionally recognised his right of ownership of the principality of Estonia. Then, Gotthard Kettler, Master of the Livonian Order, gave Magnus the portions of Livonia he had taken possession of, along with Archbishop Wilhelm von Brandenburg of the Archbishopric of Riga and his coadjutor Christoph von Mecklenburg. They refused to give him any more land, however. Once Eric XIV of Sweden became king, Magnus took quick action to involve himself in the Livonian War. He negotiated a peace with Russia and approached the burghers of Reval with an offer of goods in exchange for submission to his rule, as well as threats if they would not agree. By 6 June 1561, they submitted to him contrary to the urgings of Gotthard Kettler. King Eric's brother Johan, Duke of Finland (and later king John III of Sweden), married the Polish princess Catherine Jagiellon. Wanting to obtain his own land in Livonia, Johan loaned Poland money and then took possession of the castles that were pawned by the Poles instead of helping to support Polish foreign policy. After Johan returned to Finland, Erik XIV forbade him to deal with any foreign countries without his consent. Magnus was upset that he had been tricked out of his inheritance of Holstein. After Sweden occupied Reval, Frederick II of Denmark made a treaty with Erik XIV of Sweden in August 1561. Frederick II then negotiated a treaty with Ivan the Terrible on 7 August 1562 in order to help his brother Magnus obtain more land and stall further Swedish advances. Erik XIV did not accept these actions, and the Northern Seven Years' War among the Free City of Lübeck, Denmark, Poland, and Sweden broke out in 1563.

In 1561, the weakened Livonian Order was dissolved by the Treaty of Vilnius. Its lands were secularised as the Duchy of Livonia and assigned to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania along with the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia as a vassal state. The last Master of the order, Gotthard Kettler, became the first Duke of Courland. By doing so, he converted to Lutheranism.

Losing land and trade, Frederick II and Magnus were not faring well in Livonia. But in 1568, Erik XIV went insane, and his brother Johan III ascended to the throne of Sweden. Due to his friendship with Poland, he initiated a foreign policy in opposition to Russia. He tried to acquire more land in Livonia and attain military superiority over Denmark. After all parties had been financially drained, Frederick II informed his ally, King Sigismund II Augustus of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, that he was ready for peace. On 15 December 1570, the Treaty of Stettin was concluded. It is, however, more difficult to estimate the scope and magnitude of the support Magnus received in Livonian cities. Compared to the Harrien-Wierland gentry, the Reval city council, and hence probably the majority of citizens, demonstrated a much more reserved attitude towards Denmark and King Magnus of Livonia. Nevertheless, there is no reason to speak about any strong pro-Swedish sentiments among the residents of Reval. The citizens who had fled to The Bishopric of Dorpat or had been deported to Muscovy hailed Magnus as their saviour until 1571. The analysis indicates that during the Livonian War a pro-independence wing emerged among the Livonian gentry and townspeople, forming the so-called "Peace Party." Dismissing hostilities, these forces perceived an agreement with Muscovy as a chance to escape the atrocities of war and avoid the division of Livonia. That is why Magnus, who represented Denmark and later struck a deal with Ivan the Terrible, proved a suitable figurehead for this faction.

The Peace Party, however, had its own armed forces: scattered bands of household troops (Hofleute) under diverse command. They were united in action only in 1565 (at the Siege of Pärnu and Siege of Reval); in 1570–1571 (during another Siege of Reval that lasted 30 weeks); and in 1574–1576 in conflicts involving Sweden, Denmark and Russia. In 1575, after Russians attacked Danish claims in Livonia, Frederick II dropped out of the struggle along with Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II. After this, Johan III held off on his pursuit for more land in Livonia as Russia obtained lands that Sweden had controlled. He used the next two years of truce to position himself more advantageously. In 1578, he resumed the fight not only for Livonia, but also other parts of eastern Europe due to an understanding he made with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In 1578 Magnus retired to the Commonwealth, and his brother all but gave up his claim to lands in Livonia.

Kingdom of Livonia 1570–1578

On 10 June 1570, the Danish Duke Magnus of Holstein arrived in Moscow, where he was crowned King of Livonia. Magnus took an oath of allegiance to Ivan the Terrible as his overlord and received from him the corresponding charter for the vassal kingdom of Livonia in what Ivan termed his patrimony. The armies of Ivan the Terrible were initially successful, taking Polotsk in 1563 and Pärnu in 1575 and overrunning much of Grand Duchy of Lithuania up to Vilnius. Eventually, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Kingdom of Poland formed the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569 under the Union of Lublin. Eric XIV of Sweden did not like this and The Northern Seven Years' War between Free City of Lübeck, Denmark, Poland, and Sweden broke out. While only losing land and trade, Frederick II of Denmark and Magnus von Lyffland of Œsel-Wiek were not faring well. But in 1569 Erik XIV became insane and his brother John III of Sweden took his place. After all parties had been financially drained, Frederick II let his ally, King Zygmunt II August, know that he was ready for peace. On December 15, 1570, the Treaty of Stettin was concluded.

In the next phase of the conflict, in 1577 Ivan IV took opportunity of the Commonwealth internal strife (called the war against Gdańsk in Polish historiography), and during the reign of Stefan Batory in Poland invaded Livonia, quickly taking almost the entire territory, with the exception of Riga and Rewel. In 1578 Magnus of Livonia recognized the sovereignty of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (not ratified by the Sejm of Poland-Lithuania, or recognized by Denmark). The Kingdom of Livonia was beaten back by Muscovy on all fronts. In 1578 Magnus of Livonia retired to The Bishopric of Courland and his brother all but gave up the land in Livonia.

Duchy of Livonia 1561–1621

In 1561 during the Livonian War, The Livonian Confederation subjected itself to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania[3][4][5] with vassal dependency of it[5] and became secularized under the Union of Wilno. Eight years later, in 1569, when the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Kingdom of Poland formed the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Livonia became a joint domain administered directly by the king and grand duke.[3][5][6][7][8][9] Having rejected peace proposals from its enemies, Ivan the Terrible found himself in a difficult position by 1579, when Crimean Khanate devastated Muscovian territories and burnt down Moscow (see Russo-Crimean Wars), the drought and epidemics have fatally affected the economy, Oprichnina had thoroughly disrupted the government, while The Grand Principality of Lithuania had united with The Kingdom of Poland (1385–1569) and acquired an energetic leader, Stefan Batory, supported by Ottoman Empire (1576). Stefan Batory replied with a series of three offensives against Russia, trying to cut The Kingdom of Livonia from Russian territories. During his first offensive in 1579 with 22,000 men he retook Polotsk, during the second, in 1580, with 29,000-strong army he took Velikiye Luki, and in 1581 with a 100,000-strong army he started the Siege of Pskov. Frederick II of Denmark and Norway had trouble continuing the fight against Muscovy unlike Sweden and Poland. He came to an agreement with John III in 1580 giving him the titles in Livonia. That war would last from 1577 to 1582. Muscovy recognized Polish–Lithuanian control of Ducatus Ultradunensis only in 1582. After Magnus von Lyffland died in 1583, Poland invaded his territories in The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia and Frederick II decided to sell his rights of inheritance. Except for the island of Œsel, Denmark was out of the Baltic by 1585. As of 1598 Polish Livonia was divided onto:

- Wenden Voivodeship (województwo wendeńskie, Kieś)

- Dorpat Voivodeship (województwo dorpackie, Dorpat)

- Parnawa Voivodeship (województwo parnawskie, Parnawa)

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia 1562–1795

In the 17th century, the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, once a part of Livonia, experienced a notable economic boom. During the reign of the duke Jacob Kettler new copper and iron foundries, gunpowder mills and shipyards were opened. In Ventspils alone 120 ships were built, of which over 40 were warships. The duchy owned large fleet and established two colonies — St. Andrews Island in the estuary of Gambia River (in Africa) and Tobago Island (in the Caribbean Sea). Names from this period still survive today in these places.

Swedish Livonia 1629–1721

During the Polish–Swedish War (1600–1629) Riga and the largest part of Duchy of Livonia came under Swedish rule in 1621. During the Swedish rule Vidzeme was known as the "Swedish Bread Basket" because it supplied the larger part of the Swedish Kingdom with wheat. The rest of Latvia stayed Polish until the second partition of Poland in 1793, when it became Russian.

In 1632 the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus founded Dorpat University which became the intellectual focus for population of Livonia. The translation of the whole Bible into Latvian in 1685 by Johann Ernst Glück was subsidized by the Swedish government. Also the schools for Latvian speaking peasantry were set up in the country parishes.

Riga was the second largest city in the Swedish Empire at the time. Together with other Baltic Sea dominions, Livonia served to secure the Swedish Dominium maris baltici. In contrast to Swedish Estonia, which had submitted to Swedish rule voluntarily in 1561 and where traditional local laws remained largely untouched, the uniformity policy was applied in Swedish Livonia under Karl XI of Sweden: serfdom was abolished in the estates owned by the Swedish crown, peasants were offered education and military, administrative or ecclesiastical careers, and nobles had to transfer domains to the king in the Great Reduction. These reforms were subsequently reversed by Peter I of Russia when he conquered Livonia.

Inflanty Voivodeship 1629–1772

After the Polish–Swedish War (1600–1629) only the Southeastern part of the Duchy of Livonia remained under Polish-Lithuanian rule. Catholicism became the dominant religion in this territory, known as Inflanty or Latgale, as a result of Counter-Reformation.

Russian period (1721–1918)

In 1700, the Great Northern War broke out. The course of this war was directly linked with today's Latvian territory and the territorial claims of the Russian Empire. One of its goals was to secure the famous and rich town of Riga. In 1710, the Russian Tsar, Peter I, managed to secure Vidzeme. Through Vidzeme to Riga, Russia obtained a clear passage to Europe. Following the Third Partition of Poland, all of Latvia's territory was under Russian rule when Kurzeme was obtained by Russia in 1795.

In 1812 Napoleon's troops invaded Russia and the Prussian units under the leadership of the field marshal Yorck occupied Courland and approached Riga. The governor-general of Riga Ivan Essen set the wooden houses of the Riga suburbs on fire to deflect the invaders and thousands of city residents were left homeless. However York did not attack Riga and in December the Napoleon's army retreated.

Serfdom was abolished in Courland Governorate in 1818 and Governorate of Livonia in 1819. However all the land stayed in the hands of the German nobility. Only in 1849, a law granted a legal basis for the creation of peasant-owned farms. Reforms were slower in Latgale which was part of Vitebsk Governorate, where serfdom was only abolished in 1861 after emancipation reform. In the middle of 19th century industry developed quickly and the number of the inhabitants grew. Courland and Vidzeme became one of Russia's most developed provinces.

Religion

Latvia was predominantly Lutheran, but in the first half of the eighteenth century Moravian missionaries made significant headway, despite the opposition of the German landlords who controlled the Lutheran clergy. The Imperial government proscribed the Moravians 1743–1764. Latvian nationalism was strongly supported by a revival of the language, including the translation of many foreign works. The Imperial government sponsored the Russian Orthodox Church, as part of its program of russification, but Lutheranism remained the dominant religion, except Latgale where Catholicism was dominant. Other Protestant missions had some success including the Baptists, Methodists and Seventh Day Adventists.[10]

Latvian National Awakening

In the 19th century, the first Latvian National Awakening began among ethnic Latvian intellectuals, a movement that partly reflected similar nationalist trends elsewhere in Europe. This revival was led by the "Young Latvians" (in Latvian: jaunlatvieši) from the 1850s to the 1880s. Primarily a literary and cultural movement with significant political implications, the Young Latvians soon came into severe conflict with the Baltic Germans.

In the 1880s and 1890s the russification policy began by Alexander III was aimed at reducing the autonomy of Baltic provinces and the introduction of the Russian language in administration, court and education replacing German or Latvian (in regard to schools).

With increasing pauperization in rural areas and growing urbanization, a loose but broad leftist movement called the "New Current" arose in the late 1880s. Led by Rainis and Pēteris Stučka, editors of the newspaper Dienas Lapa, this movement was soon influenced by Marxism and led to the creation of the Latvian Social Democratic Labour Party.

Latvia in the 20th century saw an explosion of popular discontent in the 1905 Revolution.

1905 Revolution

Following the shooting of demonstrators in St. Petersburg on January 9 a wide-scale general strike began in Riga. On January 13 Russian army troops opened fire on demonstrators in Riga killing 73 and injuring 200 people. During the summer of 1905 the main revolutionary events moved to the countryside. 470 new parish administrative bodies were elected in 94% of the parishes in Latvia. The Congress of Parish Representatives was held in Riga in November. Mass meetings and demonstrations took place including violent attacks against Baltic German nobles, burning estate buildings and seizure of estate property including weapons. In the autumn of 1905 armed conflict between the German nobility and the Latvian peasants began in the rural areas of Vidzeme and Courland. In Courland, the peasants seized or surrounded several towns. In Livland the fighters controlled the Rūjiena-Pärnu railway line. Altogether, a thousand armed clashes were registered in Latvia in 1905.[11] Martial law was declared in Courland in August 1905 and in Livland in late November. Special punitive expeditions were dispatched in mid-December to suppress the movement. They executed 1170 people without trial or investigation and burned 300 peasant homes. Thousands were exiled to Siberia. In 1906 the revolutionary movement gradually subsided.

German occupation World War I

On August 1, 1914 Germany declared war on Russia and by 1915, the conflict reached Latvia. On May 7 the Germans captured Liepāja and on May 18, Talsi, Tukums and Ventspils. On June 29 the Russian Supreme Command ordered the whole population of Kurzeme evacuated, and around 400,000 refugees fled to the east. Some of them settled in Vidzeme but most continued their way to Russia. On July 19 the Russian War Minister ordered the factories of Riga evacuated together with their workers. In the summer of 1915, 30,000 railway wagons loaded with machines and equipment from factories were taken away. In August the formation of Latvian battalions known as Latvian Riflemen started. From 1915 to 1917, the Riflemen fought in the Russian army against the Germans in positions along Daugava River. In December 1916 and January 1917, they suffered heavy casualties in month-long Christmas Battles. In February 1917 Revolution broke out in Russia and in the summer the Russian army collapsed. The German offensive was successful and on 3 September 1917 they entered Riga. In November 1917, the Communist Bolsheviks took power in Russia. The Bolshevik government tried to end the war and in March 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed which gave Kurzeme and Vidzeme to the Germans. By February the Germans had occupied all of Latvia. However, after the German Revolution, on 11 November the armistice treaty between the Allies and Germany was signed thus ending World War I.[12] Great Britain declared its de facto recognition of Latvia in writing on that day as well, confirming a prior verbal communication of 23 October to Meierowitz by the British Minister for Foreign Affairs, A. J. Balfour.[13]

Independence

The idea of an independent Latvia became a reality at the beginning of the 20th century. The course of World War I activated the idea of independence. World War I directly involved Latvians and Latvian territory. Latvian riflemen (latviešu strēlnieki) fought on the Russian side during this war, and earned recognition for their bravery far into Europe. During the Russian Civil War (1917–1922), Latvians fought on both sides with a significant group (known as Latvian red riflemen) supporting the Bolsheviks. In the autumn of 1919 the red Latvian division participated in a major battle against the "white" anti-bolshevik army headed by the Russian general Anton Denikin.

Latvia was ostensibly included within the proposed Baltic German-led United Baltic Duchy,[14] but this attempt collapsed after the defeat of the German Empire in November 1918. The post-war confusion was a suitable opportunity for the development of an independent nation. Latvia proclaimed independence shortly after the end of World War I – on November 18, 1918 which is now the Independence Day in Latvia.

A series of conflicts within the territory of Latvia during 1918–1920 is commonly known as the Latvian War of Independence. In December 1918 Soviet Russia invaded the new republic and rapidly conquered almost all the territory of Latvia, Riga itself was captured by the Soviet Army on 4 April 1919, with the exception of a small territory near Liepāja. The Latvian Socialist Soviet Republic was proclaimed on 17 December 1918 with the political, economic, and military backing of the Bolshevik government of Soviet Russia. On March 3, 1919 German and Latvian forces commenced a counterattack against the forces of Soviet Latvia. On 22 May 1919 Riga was recaptured. In June 1919 collisions started between the Baltische Landeswehr on one side and the Estonian 3rd division on the other.[15] The 3rd division defeated the German forces in the Battle of Wenden on June 23. An armistice was signed at Strazdumuiža, under the terms of which the Germans had to leave Latvia.[15] However the German forces instead of leaving, were incorporated into the West Russian Volunteer Army.[15] On October 5 it commenced an offensive on Riga taking the west bank of the Daugava River but on November 11 was defeated by Latvian forces and by the end of the month, driven from Latvia. On January 3, 1920 the united Latvian and Polish forces launched an attack on the Soviet army in Latgalia and took Daugavpils. By the end of January they reached the etnographic border of Latvia. On August 11, 1920 according to the Latvian–Soviet Peace Treaty ("Treaty of Riga") Soviet Russia relinquished authority over the Latvian nation and claims to Latvian territory "once and for all times".

The international community (United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Italy and Japan) recognized Latvia's independence on January 26, 1921, and the recognition from many other countries followed soon. In this year Latvia also became a member of the League of Nations (September 22, 1921).

In April 1920 elections to the Constituent assembly were held. In May 1922 the Constitution of Latvia and in June the new Law on Elections were passed, opening the way to electing the parliament- Saeima. At Constituent Assembly, the law on the land reform was passed, which expropriated the manor lands. Landowners were left with 50 hectares each and their land was distributed to the landless peasants without cost. In 1897, 61.2% of the rural population had been landless; by 1936, that percentage had been reduced to 18%. The extent of cultivated land surpassed the pre-war level already in 1923.[16]

Because of the world economic crisis there was a growing dissatisfaction among the population at the beginning of the 1930s. In Riga on May 15, 1934, Prime Minister Kārlis Ulmanis, one of the fathers of Latvian independence, took power by a bloodless coup d'état: the activities of the parliament (the Saeima) and all the political parties were suspended.

Rapid economic growth took place in the second half of the 1930s, due to which Latvia reached one of the highest living standards in Europe.[17] Because of improving living standards in Latvian society, there was no serious opposition to the authoritarian rule of the Prime Minister Kārlis Ulmanis and no possibility of it arising.

World War II

Soviet Occupation

The Soviet Union guaranteed its interests in the Baltics with the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany on August 23, 1939. Under threat of invasion,[note 1] Latvia (along with Estonia and Lithuania) signed a mutual assistance pact with Soviet Union, providing for the stationing of up to 25,000 Soviet troops on Latvian soil. Following the initiative from Nazi Germany, Latvia on October 30, 1939 concluded an agreement to repatriate ethnic Germans in the wake of the impeding Soviet takeover.

Seven months later, the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov accused the Baltic states of conspiracy against the Soviet Union. On June 16, 1940, threatening an invasion,[note 2] Soviet Union issued an ultimatum demanding that the government be replaced and that an unlimited number of Soviet troops be admitted.[20] Knowing that the Red Army had entered Lithuania a day before, that its troops were massed along the eastern border and mindful of the Soviet military bases in Western Latvia, the government acceded to the demands, and Soviet troops occupied the country on June 17. Staged elections were held July 14–15, 1940, whose results were announced in Moscow 12 hours before the polls closed; Soviet documents show the election results were forged. The newly elected "People's Assembly" declared Latvia a Socialist Soviet Republic and applied for admission into the Soviet Union on July 21. Latvia was incorporated into the Soviet Union on August 5, 1940. The overthrown Latvian government continued to function in exile while the republic was under the Soviet control.

In the spring of 1941, the Soviet central government began planning the mass deportation of anti-Soviet elements from the occupied Baltic states. In preparation, General Ivan Serov, Deputy People's Commissar of Public Security of the Soviet Union, signed the Serov Instructions, "Regarding the Procedure for Carrying out the Deportation of Anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia." During the night of 13–14 June 1941, 15,424 inhabitants of Latvia — including 1,771 Jews and 742 ethnic Russians — were deported to camps and special settlements, mostly in Siberia.[21] 35,000 people were deported in the first year of Soviet occupation (131,500 across the Baltics).

Occupation of Latvia by Nazi Germany

The Nazi invasion, launched a week later, cut short immediate plans to deport several hundred thousand more from the Baltics. Nazi troops occupied Riga on July 1, 1941. Immediately after the installment of German authority, a process of eliminating the Jewish and Gypsy population began, with many killings taking place in Rumbula. The killings were committed by the Einsatzgruppe A, the Wehrmacht and Marines (in Liepāja), as well as by Latvian collaborators, including the 500-1,500 members of the infamous Arajs Commando (which alone killed around 26,000 Jews) and the 2,000 or more Latvian members of the SD.[22][23] By the end of 1941 almost the entire Jewish population was killed or placed in the concentration camps. In addition, some 25,000 Jews were brought from Germany, Austria and the present-day Czech Republic, of whom around 20,000 were killed. The Holocaust claimed approximately 85,000 lives in Latvia,[22] the vast majority of whom were Jews.

A large number of Latvians resisted the German occupation. The resistance movement was divided between the pro-independence units under the Latvian Central Council and the pro-Soviet units under the Latvian Partisan Movement Headquarters (Латвийский штаб партизанского движения) in Moscow. Their Latvian commander was Arturs Sproģis. The Nazis planned to Germanise the Baltics after the war.[22] In 1943 and 1944 two divisions of Waffen-SS were formed from Latvian conscripts and volunteers to help Germany against the Red Army.

Soviet era

In 1944, when the Soviet military advances reached the area heavy fighting took place in Latvia between German and Soviet troops, which ended with another German defeat. Riga was re-captured by the Soviet Red Army on 13 October 1944. During the course of the war, both occupying forces conscripted Latvians into their armies, in this way increasing the loss of the nation's "live resources". In 1944, part of the Latvian territory once more came under Soviet control and Latvian national partisans began their fight against another occupier – the Soviet Union. 160,000 Latvian inhabitants took refuge from the Soviet army by fleeing to Germany and Sweden. The first post-war years were marked by particularly dismal and sombre events in the fate of the Latvian nation. On March 25, 1949, 43,000 rural residents ("kulaks") and Latvian patriots ("nationalists") were deported to Siberia in a sweeping repressive Operation Priboi in all three Baltic States, which was carefully planned and approved in Moscow already on January 29, 1949. All together 120,000 Latvian inhabitants were imprisoned or deported to Soviet concentration camps (the Gulag). Some managed to escape arrest and joined the partisans.

In the post-war period, Latvia was forced to adopt Soviet farming methods and the economic infrastructure developed in the 1920s and 1930s was eradicated. Rural areas were forced into collectivisation. The massive influx of labourers, administrators, military personnel and their dependents from Russia and other Soviet republics started. By 1959 about 400,000 persons arrived from other Soviet republics and the ethnic Latvian population had fallen to 62%.[24] An extensive programme to impose bilingualism was initiated in Latvia, limiting the use of Latvian language in favor of Russian. All of the minority schools (Jewish, Polish, Belarusian, Estonian, Lithuanian) were closed down leaving only two languages of instructions in the schools- Latvian and Russian.[25] The Russian language were taught notably, as well as Russian literature, music and history of Soviet Union (actually- history of Russia).

On 5 March 1953 Joseph Stalin died and his successor became Nikita Khrushchev. The period known as the Khrushchev Thaw began but attempts by the national communists led by Eduards Berklavs to gain a degree of autonomy for the republic and protect the rapidly deteriorating position of the Latvian language were not successful. In 1959 after Krushchev's visit in Latvia national communists were stripped of their posts and Berklavs was deported to Russia.

Because Latvia had still maintained a well-developed infrastructure and educated specialists it was decided in Moscow that some of the Soviet Union's most advanced manufacturing factories were to be based in Latvia. New industry was created in Latvia, including a major machinery factory RAF in Jelgava, electrotechnical factories in Riga, chemical factories in Daugavpils, Valmiera and Olaine, as well as food and oil processing plants.[26] However, there were not enough people to operate the newly built factories. In order to expand industrial production, more immigrants from other Soviet republics were transferred into the country, noticeably decreasing the proportion of ethnic Latvians.

By 1989, the ethnic Latvians comprised about 52% of the population (1,387,757), compared to a pre-war proportion of 77% (1,467,035). In 2005 there were 1,357,099 ethnic Latvians, showing a real decrease in the titular population. Proportionately, however, the titular nation already comprises approximately 60% of the total population of Latvia (2,375,000).

Restoration of independence

Liberalization in the communist regime began in the mid-1980s in the USSR with the perestroika and glasnost instituted by Mikhail Gorbachev. In Latvia, several mass political organizations were constituted that made use of this opportunity – Popular Front of Latvia (Tautas Fronte), Latvian National Independence Movement (Latvijas Nacionālās Neatkarības Kustība) and Citizens' Congress (Pilsoņu kongress). These groups began to agitate for the restoration of national independence.

On the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact (August 23, 1989) to the fate of the Baltic nations, Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians joined hands in a human chain, the Baltic Way, that stretched 600 kilometers from Tallinn, to Riga, to Vilnius. It symbolically represented the united wish of the Baltic States for independence.

Subsequent steps towards full independence were taken on May 4, 1990. The Latvian SSR Supreme Council, elected in the first democratic elections since the 1930s, adopted a declaration restoring independence that included a transition period between autonomy within the Soviet Union and full independence. In January 1991, however, pro-communist political forces attempted to restore Soviet power with the use of force. Latvian demonstrators managed to stop the Soviet troops from re-occupying strategic positions (January 1991 events in Latvia). On August 21, after unsuccessful attempt at a coup d'état in Moscow, parliament voted for an end to the transition period, thus restoring Latvia's pre-war independence. On September 6, 1991 Latvian independence was once again recognized by the Soviet Union.

Modern history

Soon after reinstating independence, Latvia, which had been a member of the League of Nations prior to World War II, became a member of the United Nations. In 1992, Latvia became eligible for the International Monetary Fund and in 1994 took part in the NATO Partnership for Peace program in addition to signing the free trade agreement with the European Union. Latvia became a member of the European Council as well as a candidate for the membership in the European Union and NATO. Latvia was the first of the three Baltic nations to be accepted into the World Trade Organization.

At the end of 1999 in Helsinki, the heads of the European Union governments invited Latvia to begin negotiations regarding accession to the European Union. In 2004, Latvia's most important foreign policy goals, membership of the European Union and NATO, were fulfilled. On April 2, Latvia became a member of NATO and on May 1, Latvia, along with the other two Baltic States, became a member of the European Union. Around 67% had voted in favor of EU membership in a September 2003 referendum with turnout at 72.5 percent.

See also

- Dissolution of the Soviet Union

- History of Estonia

- History of Europe

- History of the European Union

- History of Lithuania

- History of Germany

- History of Russia

- History of Sweden

- Latvian independence movement (1940–1991)

- Latvian diplomatic service (1940–1991)

- List of Presidents of Latvia

- Prime Minister of Latvia

- Livonia

- Politics of Latvia

|

Notes

- ↑ Soviet-Latvian negotiations started on 2 October 1939 and on the following day Latvia's Minister of Foreign Affairs Vilhelms Munters informed his government that Josif Stalin had said that "as for the Germans, [there is no obstacle], we can occupy you" and threatened that the USSR could also seize "territory with a Russian minority."[18]

- ↑ and presenting the ultimatum and accusations of violation by Latvia of the terms of mutual assistance treaty of 1939, Molotov issued an overt threat to "take action" to secure compliance with the terms of ultimatum – see report of Latvian Chargé d'affaires, Fricis Kociņš, regarding the talks with soviet Foreign Commissar Molotov.[19]

References

- ↑ Data: 3000 BC to 1500 BC - The Ethnohistory Project

- ↑ British Museum Collection

- 1 2 Alfredas Bumblauskas (2005). Senosios Lietuvos istorija 1009 - 1795 (in Latvian). Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla. pp. 256–259. ISBN 9986-830-89-3.

- ↑ Robert Auty (1981). D. Obolensky, ed. Companion to Russian Studies: Volume 1 Vol 1 Introduction to Russian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-521-28038-9.

- 1 2 3 Szilvia Rédey, Endre Bojtár (1999). Foreword to the Past: a cultural history of the Baltic People. Central European University Press. p. 172. ISBN 963-9116-42-4.

- ↑ Norman Davies (1996). Europe: a History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 555. ISBN 0-19-820171-0.

- ↑ George Miller (historian) (1832). "Modern History". History, philosophically issustrated, from the fall of the Roman empire to the French revolution. p. 258.

- ↑ Alfrēds Bīlmanis (1945). Baltic Essays. The Latvian Legation. pp. 69–80. OCLC 1535884.

- ↑ Beresford James Kidd (1933). The Counter-reformation, 1550-1600. Society for promoting Christian knowledge. p. 121. ISBN 0-313-22193-6.

- ↑ Kenneth Scott Latourette, Christianity in a Revolutionary Age (1959) 2:199

- ↑ Bleiere, Daina; Ilgvars Butulis; Antonijs Zunda; Aivars Stranga; Inesis Feldmanis (2006). History of Latvia : the 20th century. Riga: Jumava. p. 68. ISBN 9984-38-038-6. OCLC 70240317.

- ↑ Mangulis, Visvaldis. Latvia in the Wars of the 20th Century Princeton Junction: Cognition Books, 1983, xxi, 207p. ISBN 0-912881-00-3

- ↑ Laserson, Max. The Recognition of Latvia, The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 37, No. 2 (April , 1943), pp. 233-247

- ↑ The Story of the Estonian Republic — 1918–1940 Estonica.org

- 1 2 3 Colonel Jaan Maide. Ülevaade Eesti Vabadussõjast (1918–1920) (Overview on Estonian War of Independence) (in Estonian).

- ↑ Bleiere, Daina; Ilgvars Butulis; Antonijs Zunda; Aivars Stranga; Inesis Feldmanis (2006). History of Latvia : the 20th century. Riga: Jumava. p. 195. ISBN 9984-38-038-6. OCLC 70240317.

- ↑ {{Expand section cite web |author =Dr. Raimonds Cerūzis |year =2007-2008 |title =The Fight for Independence and the Republic of Latvia |url =http://www.li.lv/index.php?Itemid=446&id=71&option=com_content&task=view |work =The Latvian Institute |publisher =The University of Latvia |accessdate =2008-08-14 }}

- ↑ Dr. hab.hist. Inesis Feldmanis (2004). "The Occupation of Latvia: Aspects of History and International Law". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Latvia. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ↑ I.Grava-Kreituse, I.Feldmanis, J.Goldmanis, A.Stranga. (1995). Latvijas okupācija un aneksija 1939-1940: Dokumenti un materiāli. (The Occupation and Annexation of Latvia: 1939-1940. Documents and Materials.) (in Latvian). Preses nams. pp. 348–350.

- ↑ see text of ultimatum; text in Latvian: I.Grava-Kreituse, I.Feldmanis, J.Goldmanis, A.Stranga. (1995). Latvijas okupācija un aneksija 1939-1940: Dokumenti un materiāli. (The Occupation and Annexation of Latvia: 1939-1940. Documents and Materials.). Preses nams. pp. 340–342.

- ↑ Elmārs Pelkaus, ed. (2001). Aizvestie: 1941. gada 14. jūnijā (in Latvian, English, and Russian). Riga: Latvijas Valsts arhīvs; Nordik. ISBN 9984-675-55-6. OCLC 52264782.

- 1 2 3 Ezergailis, A. The Holocaust in Latvia, 1996

- ↑ Simon Wiesenthal Center Multimedia Learning Center Online

- ↑ Bleiere, Daina; Ilgvars Butulis; Antonijs Zunda; Aivars Stranga; Inesis Feldmanis (2006). History of Latvia : the 20th century. Riga: Jumava. p. 418. ISBN 9984-38-038-6. OCLC 70240317.

- ↑ Bleiere, Daina; Ilgvars Butulis; Antonijs Zunda; Aivars Stranga; Inesis Feldmanis (2006). History of Latvia : the 20th century. Riga: Jumava. p. 411. ISBN 9984-38-038-6. OCLC 70240317.

- ↑ Bleiere, Daina; Ilgvars Butulis; Antonijs Zunda; Aivars Stranga; Inesis Feldmanis (2006). History of Latvia : the 20th century. Riga: Jumava. p. 379. ISBN 9984-38-038-6. OCLC 70240317.

Further reading

- Bilmanis, Alfreds. A History of Latvia (1970)

- Eglitis, Daina Stukuls. Imagining the Nation: History, Modernity, and Revolution in Latvia (Post-Communist Cultural Studies) (2005)

- Lumans; Valdis O. Latvia in World War II (Fordham University Press, 2006) online edition

- Plakans, Andrejs. Historical Dictionary of Latvia (2008)

- Plakans, Andrejs. The Latvians: A Short History (1995) excerpt and text search

External links

- History of Latvia The Route from the Vikings to the Greeks

External links

- History of Latvia; A Brief Survey (en)

- History of Latvia: Primary Documents

- Issues of the History of Latvia: 1939-1991

- Castle ruins in Latvia

- Myths of Latvian History (en)

- Occupation of Latvia (PDF file 2.85MB)

- Latvia: Year of horror (1940)

- The Story of Latvia, by Arveds Svabe

- Historical maps of Latvia in the 16th, 17th and 18th century

- Medieval Castles of Latvia

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||