Isoelastic utility

In economics, the isoelastic function for utility, also known as the isoelastic utility function, or power utility function is used to express utility in terms of consumption or some other economic variable that a decision-maker is concerned with. The isoelastic utility function is a special case of HARA and at the same time is the only class of utility functions with constant relative risk aversion, which is why it is also called the CRRA utility function.

It is

where  is consumption,

is consumption,  the associated utility, and

the associated utility, and  is a constant.[1] Since additive constant terms in objective functions do not affect optimal decisions, the term –1 in the numerator can be, and usually is, omitted (except when establishing the limiting case of

is a constant.[1] Since additive constant terms in objective functions do not affect optimal decisions, the term –1 in the numerator can be, and usually is, omitted (except when establishing the limiting case of  as below).

as below).

When the context involves risk, the utility function is viewed as a von Neumann-Morgenstern utility function, and the parameter  is a measure of risk aversion.

is a measure of risk aversion.

The isoelastic utility function is a special case of the hyperbolic absolute risk aversion (HARA) utility functions, and is used in analyses that either include or do not include underlying risk.

Empirical parametrization

There is substantial debate in the economics and finance literature with respect to the empirical value of  . While relatively high values of

. While relatively high values of  (as high as 50 in some models) are necessary to explain the behavior of asset prices, some controlled experiments have documented behavior that is more consistent with values of

(as high as 50 in some models) are necessary to explain the behavior of asset prices, some controlled experiments have documented behavior that is more consistent with values of  as low as one.

as low as one.

Risk aversion features

This and only this utility function has the feature of constant relative risk aversion. Mathematically this means that  is a constant, specifically

is a constant, specifically  . In theoretical models this often has the implication that decision-making is unaffected by scale. For instance, in the standard model of one risk-free asset and one risky asset, under constant relative risk aversion the fraction of wealth optimally placed in the risky asset is independent of the level of initial wealth.[2][3]

. In theoretical models this often has the implication that decision-making is unaffected by scale. For instance, in the standard model of one risk-free asset and one risky asset, under constant relative risk aversion the fraction of wealth optimally placed in the risky asset is independent of the level of initial wealth.[2][3]

Special cases

-

: this corresponds to risk neutrality, because utility is linear in c.

: this corresponds to risk neutrality, because utility is linear in c. -

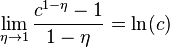

: by virtue of l'Hôpital's rule, the limit of

: by virtue of l'Hôpital's rule, the limit of  is

is  as

as  goes to one:

goes to one:

- which justifies the convention of using the limiting value u(c) = ln c when

.

.

-

→

→  : this is the case of infinite risk aversion.

: this is the case of infinite risk aversion.

See also

References

- ↑ Ljungqvist, Lars; Sargent, Thomas J. (2000). Recursive Macroeconomic Theory. London: MIT Press. p. 451. ISBN 0262194511.

- ↑ Arrow, K. J. (1965). "The theory of risk aversion". Aspects of the Theory of Risk Bearing. Helsinki: Yrjo Jahnssonin Saatio. Reprinted in: Essays in the Theory of Risk Bearing. Chicago: Markham. 1971. pp. 90–109. ISBN 0841020019.

- ↑ Pratt, J. W. (1964). "Risk aversion in the small and in the large". Econometrica 32 (1–2): 122–136. JSTOR 1913738.

External links

- Wakker, P. P. (2008), Explaining the characteristics of the power (CRRA) utility family. Health Economics, 17: 1329–1344.

- Closed form solution of a consumption savings problem with iso-elastic utility