Politeness

"Your eel, I think, Sir?" ---- Cartoon in Punch magazine: 28 July 1920

Politeness is the practical application of good manners or etiquette. It is a culturally defined phenomenon, and therefore what is considered polite in one culture can sometimes be quite rude or simply eccentric in another cultural context.

While the goal of politeness is to make all of the parties relaxed and comfortable with one another, these culturally defined standards at times may be manipulated to inflict shame on a designated party.

Anthropologists Penelope Brown and Stephen Levinson identified two kinds of politeness, deriving from Erving Goffman's concept of face:

- Negative politeness: Making a request less infringing, such as "If you don't mind..." or "If it isn't too much trouble..."; respects a person's right to act freely. In other words, deference. There is a greater use of indirect speech acts.

- Positive politeness: Seeks to establish a positive relationship between parties; respects a person's need to be liked and understood. Direct speech acts, swearing and flouting Grice's maxims can be considered aspects of positive politeness because:

- they show an awareness that the relationship is strong enough to cope with what would normally be considered impolite (in the popular understanding of the term);

- they articulate an awareness of the other person's values, which fulfills the person's desire to be accepted.

Some cultures seem to prefer one of these kinds of politeness over the other. In this way politeness is culturally bound.

History

During the Enlightenment era, a self-conscious process of the imposition of polite norms and behaviours became a symbol of being a genteel member of the upper class. Upwardly mobile middle class bourgeoisie increasingly tried to identify themselves with the elite through their adopted artistic preferences and their standards of behaviour. They became preoccupied with precise rules of etiquette, such as when to show emotion, the art of elegant dress and graceful conversation and how to act courteously, especially with women. Influential in this new discourse was a series of essays on the nature of politeness in a commercial society, penned by the philosopher Lord Shaftesbury in the early 18th century.[1] Shaftesbury defined politeness as the art of being pleasing in company:

- 'Politeness' may be defined a dext'rous management of our words and actions, whereby we make other people have better opinion of us and themselves.[2]

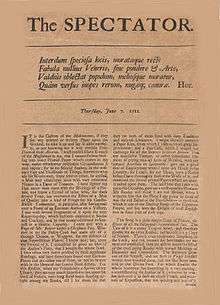

Periodicals, such as The Spectator, founded as a daily publication by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in 1711, gave regular advice to its readers on how to be a polite gentleman. It's stated goal was "to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality...to bring philosophy out of the closets and libraries, schools and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea-tables and coffeehouses" It provided its readers with educated, topical talking points, and advice in how to carry on conversations and social interactions in a polite manner.[3]

The art of polite conversation and debate was particularly cultivated in the coffeehouses of the period. Conversation was supposed to conform to a particular manner, with the language of polite and civil conversation considered to be essential to the conduct of coffeehouse debate and conversation.[4] The concept of 'civility' referred to a desired social interaction which valued sober and reasoned debate on matters of interest.[5] Established rules and procedures for proper behaviour as well as conventions, were outlined by gentleman's clubs, such as Harrington's Rota Club. Periodicals, including The Tatler and The Spectator, infused politeness into English coffeehouse conversation, as their explicit purpose lay in the reformation of English manners and morals.[6]

Techniques

%2C_2009_Amberley_Bus_Day.jpg)

- Expressing uncertainty and ambiguity through hedging and indirectness.

- Polite lying

- Use of euphemisms (which make use of ambiguity as well as connotation)

- Preferring tag questions to direct statements, such as "You were at the store, weren't you?"

- modal tags request information of which the speaker is uncertain. "You didn't go to the store yet, did you?"

- affective tags indicate concern for the listener. "You haven't been here long, have you?"

- softeners reduce the force of what would be a brusque demand. "Hand me that thing, could you?"

- facilitative tags invite the addressee to comment on the request being made. "You can do that, can't you?"

Some studies[7][8] have shown that women are more likely to use politeness formulas than men, though the exact differences are not clear. Most current research has shown that gender differences in politeness use are complex,[9] since there is a clear association between politeness norms and the stereotypical speech of middle class white women, at least in the UK and US. It is therefore unsurprising that women tend to be associated with politeness more and their linguistic behaviour judged in relation to these politeness norms.

Linguistic devices

Besides and additionally to the above, many languages have specific means to show politeness, deference, respect, or a recognition of the social status of the speaker and the hearer. There are two main ways in which a given language shows politeness: in its lexicon (for example, employing certain words in formal occasions, and colloquial forms in informal contexts), and in its morphology (for example, using special verb forms for polite discourse). The T-V distinction is a common example in Western languages.

Criticism of the theory

Brown and Levinson's theory of politeness has been criticised as not being universally valid, by linguists working with East-Asian languages, including Japanese. Matsumoto[10] and Ide[11] claim that Brown and Levinson assume the speaker's volitional use of language, which allows the speaker's creative use of face-maintaining strategies toward the addressee. In East-Asian cultures like Japan, politeness is achieved not so much on the basis of volition as on discernment (wakimae, finding one's place), or prescribed social norms. Wakimae is oriented towards the need for acknowledgment of the positions or roles of all the participants as well as adherence to formality norms appropriate to the particular situation.

Japanese is perhaps the most widely known example of a language that encodes politeness at its very core. Japanese has two main levels of politeness, one for intimate acquaintances, family and friends, and one for other groups, and verb morphology reflects these levels. Besides that, some verbs have special hyper-polite suppletive forms. This happens also with some nouns and interrogative pronouns. Japanese also employs different personal pronouns for each person according to gender, age, rank, degree of acquaintance, and other cultural factors. See Honorific speech in Japanese, for further information.

See also

- Formality

- Intercultural competence

- Polite fiction

- Politeness maxims (Geoffrey Leech)

- Politeness theory

- Social graces

References

- ↑ Lawrence E. Klein (1994). Shaftesbury and the Culture of Politeness: Moral Discourse and Cultural Politics in Early Eighteenth-Century England. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ "The Third Earl of Shaftesbury and the Progress of Politeness". Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ↑ "Information Britain". Information Britain. 2010-03-01. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ Klein, 1996 p 34

- ↑ Cowan, 2005. p 101

- ↑ Mackie, 1998. p 1

- ↑ Lakoff, R. (1975) Language and Woman's Place. New York: Harper & Row.

- ↑ Beeching, K. (2002) Gender, Politeness and Pragmatic Particles in French. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- ↑ Holmes, J. 1995 Women Men and Language, Longman; Mills, Gender and Politeness, Cambridge University Press, 2003

- ↑ Matsumoto, Y. (1988) "Reexamination of the universality of Face: Politeness phenomena in Japanese". Journal of Pragmatics 12: 403–426.

- ↑ Ide, S. (1989) "Formal forms and discernment: two neglected aspects of universals of linguistic politeness". Multilingua 8(2/3): 223–248.

Further reading

- Brown, P. and Levinson, S. (1987) Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Holmes, J. 1995 Women Men and Politeness London: Longman

- Mills, S. (2003) Gender and Politeness, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Watts, R.J. (2003) Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Spencer-Oatey, H. (2000) Culturally Speaking, Continuum.

- Kadar, D. and M. Haugh (2013) "Understanding Politeness". Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Look up politeness in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Politeness. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Politeness |

- Model Citizenship Real-life Examples of Civil Politeness

- Sociolinguistics: Politeness

- Sociolinguistics: Politeness in Spanish

- wiki project in comparative politeness: European Communicative Strategies (ECSTRA) (directed by Joachim Grzega)