Position and momentum space

In physics and geometry, there are two intertwined vector spaces.

Position space (also real space or coordinate space) is the set of all position vectors r of an object in space (usually 3D). The position vector defines a point in space. If the position vector varies with time it will trace out a path or surface, such as the trajectory of a particle.

Momentum space is the set of all momentum vectors p of an object in space (again usually 3D). The momentum vector corresponds to the motion of the object. The idea transcends all of physics, classical and quantum mechanics. However, in quantum mechanics, the De Broglie relation p = ħk states that momentum and wavevectors for a free particle are proportional to each other. The set of all wavevectors k forms k-space.[1] and when it is unambiguous, the terms "momentum" (symbol p, also a vector) and "wavevector" are used interchangeably. The De Broglie relation is not true in a crystal.

The duality between position and momentum is an example of Pontryagin duality.

The position vector r has dimensions of length, the momentum vector has units of [mass][length][time]−1, and the k-vector has dimensions of reciprocal length, so k is the frequency analogue of r, just as angular frequency ω is the inverse quantity and frequency analogue of time t. Physical phenomena can be described using either the positions of particles, or their momenta, both formulations equivalently provide the same information about the system in consideration. Usually r is more intuitive and simpler than k, though the converse is also true, such as in solid-state physics.

Position and momentum spaces in classical mechanics

Lagrangian mechanics

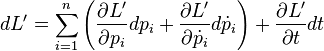

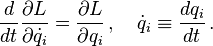

Most often in Lagrangian mechanics, the Lagrangian L(q, dq/dt, t) is in configuration space, where q = (q1, q2,..., qn) is an n-tuple of the generalized coordinates. The Euler–Lagrange equations of motion are

(One overdot indicates one time derivative). Introducing the definition of canonical momentum for each generalized coordinate

the Euler–Lagrange equations take the form

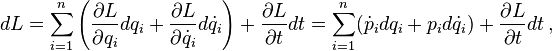

The Lagrangian can be expressed in momentum space also,[2] L′(p, dp/dt, t), where p = (p1, p2,..., pn) is an n-tuple of the generalized momenta. A Legendre transformation is performed to change the variables in the total differential of the generalized coordinate space Lagrangian;

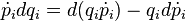

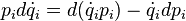

where the definition of generalized momentum and Euler–Lagrange equations have replaced the partial derivatives of L. The product rule for differentials[nb 1] allows the exchange of differentials in the generalized coordinates and velocities for the differentials in generalized momenta and their time derivatives,

which after substitution simplifies and rearranges to

Now, the total differential of the momentum space Lagrangian L′ is

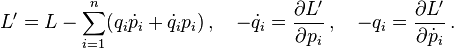

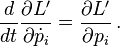

so by comparison of differentials of the Lagrangians, the momenta, and their time derivatives, the momentum space Lagrangian L′ and the generalized coordinates derived from L′ are respectively

Combining the last two equations gives the momentum space Euler–Lagrange equations

The advantage of the Legendre transformation is that the relation between the new and old functions and their variables are obtained in the process. Both the coordinate and momentum forms of the equation are equivalent and contain the same information about the dynamics of the system. This form may be more useful when momentum or angular momentum enters the Lagrangian.

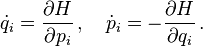

Hamiltonian mechanics

In Hamiltonian mechanics, unlike Lagrangian mechanics which uses either the all the coordinates or the momenta, the Hamiltonian equations of motion place coordinates and momenta on equal footing. For a system with Hamiltonian H(q, p, t), the equations are

Position and momentum spaces in quantum mechanics

In quantum mechanics, a particle is described by a quantum state. This quantum state can be represented as a superposition (i.e. a linear combination as a weighted sum) of basis states. In principle one is free to choose the set of basis states, as long as they span the space. If one chooses the eigenfunctions of the position operator as a set of basis functions, one speaks of a state as a wave function  (r) in position space (our ordinary notion of space in terms of length). The familiar Schrödinger equation in terms of the position r is an example of quantum mechanics in the position representation.[3]

(r) in position space (our ordinary notion of space in terms of length). The familiar Schrödinger equation in terms of the position r is an example of quantum mechanics in the position representation.[3]

By choosing the eigenfunctions of a different operator as a set of basis functions, one can arrive at a number of different representations of the same state. If one picks the eigenfunctions of the momentum operator as a set of basis functions, the resulting wave function  (k) is said to be the wave function in momentum space.[3]

(k) is said to be the wave function in momentum space.[3]

Relation between space and reciprocal space

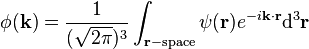

The momentum representation of a wave function is very closely related to the Fourier transform and the concept of frequency domain. Since a quantum mechanical particle has a frequency proportional to the momentum (de Broglie's equation given above), describing the particle as a sum of its momentum components is equivalent to describing it as a sum of frequency components (i.e. a Fourier transform).[4] This becomes clear when we ask ourselves how we can transform from one representation to another.

Functions and operators in position space

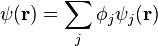

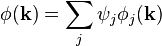

Suppose we have a three-dimensional wave function in position space  (r), then we can write this functions as a weighted sum of orthogonal basis functions

(r), then we can write this functions as a weighted sum of orthogonal basis functions  j(r):

j(r):

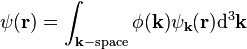

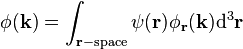

or, in the continuous case, as an integral

It is clear that if we specify the set of functions  j(r), say as the set of eigenfunctions of the momentum operator, the function

j(r), say as the set of eigenfunctions of the momentum operator, the function  (k) holds all the information necessary to reconstruct

(k) holds all the information necessary to reconstruct  (r) and is therefore an alternative description for the state

(r) and is therefore an alternative description for the state  .

.

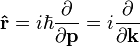

In quantum mechanics, the momentum operator is given by

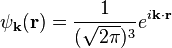

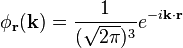

(see matrix calculus for the denominator notation) with appropriate domain. The eigenfunctions are

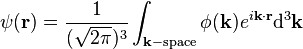

and eigenvalues ħk. So

and we see that the momentum representation is related to the position representation by a Fourier transform.[5]

Functions and operators in momentum space

Conversely, a three-dimensional wave function in momentum space  (k) as a weighted sum of orthogonal basis functions

(k) as a weighted sum of orthogonal basis functions  j(k):

j(k):

or as an integral:

the position operator is given by

with eigenfunctions

and eigenvalues r. So a similar decomposition of  (k) can be made in terms of the eigenfunctions of this operator, which turns out to be the inverse Fourier transform:[5]

(k) can be made in terms of the eigenfunctions of this operator, which turns out to be the inverse Fourier transform:[5]

Unitary equivalence between position and momentum operator

The r and p operators are unitarily equivalent, with the unitary operator being given explicitly by the Fourier transform. Thus they have the same spectrum. In physical language, p acting on momentum space wave functions is the same as r acting on position space wave functions (under the image of the Fourier transform).

Reciprocal space and crystals

For an electron (or other particle) in a crystal, its value of k relates almost always to its crystal momentum, not its normal momentum. Therefore k and p are not simply proportional but play different roles. See k·p perturbation theory for an example. Crystal momentum is like a wave envelope that describes how the wave varies from one unit cell to the next, but does not give any information about how the wave varies within each unit cell.

When k relates to crystal momentum instead of true momentum, the concept of k-space is still meaningful and extremely useful, but it differs in several ways from the non-crystal k-space discussed above. For example, in a crystal's k-space, there is an infinite set of points called the reciprocal lattice which are "equivalent" to k = 0 (this is analogous to aliasing). Likewise, the "first Brillouin zone" is a finite volume of k-space, such that every possible k is "equivalent" to exactly one point in this region.

For more details see reciprocal lattice.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ For two functions u and v, the differential of the product is d(uv) = udv + vdu.

References

- ↑ Eisberg, R.; Resnick, R. (1985). Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei, and Particles (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-873730.

- ↑ Hand & Finch, p.190, Analytical Mechanics, 2008

- 1 2 Peleg, Y.; Pnini, R.; Zaarur, E.; Hecht, E. (2010). Quantum Mechanics (Schaum's Outline Series) (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-071-623582.

- ↑ Abers, E. (2004). Quantum Mechanics. Addison Wesley, Prentice Hall Inc. ISBN 978-0-131-461000.

- 1 2 R. Penrose (2007). The Road to Reality. Vintage books. ISBN 0-679-77631-1.

![d\left[L - \sum_{i=1}^n(q_i\dot{p}_i + \dot{q}_i p_i)\right] = -\sum_{i=1}^n (\dot{q}_i d p_i + q_i d\dot{p}_i ) + \frac{\partial L }{\partial t}dt \,.](../I/m/d98eeef6f5089210c6a0076ddefb9e60.png)