Position operator

In quantum mechanics, the position operator is the operator that corresponds to the position observable of a particle. The eigenvalue of the operator is the position vector of the particle.[1]

Introduction

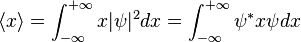

In one dimension, the square modulus of the wave function,  , represents the probability density of finding the particle at position

, represents the probability density of finding the particle at position  . Hence the expected value of a measurement of the position of the particle is

. Hence the expected value of a measurement of the position of the particle is

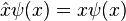

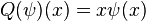

Accordingly, the quantum mechanical operator corresponding to position is  , where

, where

The circumflex over the x on the left side indicates an operator, so that this equation may be read The result of the operator x acting on any function ψ(x) equals x multiplied by ψ(x). Or more simply, the operator x multiplies any function ψ(x) by x.

Eigenstates

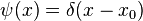

The eigenfunctions of the position operator, represented in position space, are Dirac delta functions.

To show this, suppose that  is an eigenstate of the position operator with eigenvalue

is an eigenstate of the position operator with eigenvalue  . We write the eigenvalue equation in position coordinates,

. We write the eigenvalue equation in position coordinates,

recalling that  simply multiplies the function by

simply multiplies the function by  in the position representation. Since

in the position representation. Since  is a variable while

is a variable while  is a constant,

is a constant,  must be zero everywhere except at

must be zero everywhere except at  . The normalized solution to this is

. The normalized solution to this is

Although such a state is physically unrealizable and, strictly speaking, not a function, it can be thought of as an "ideal state" whose position is known exactly (any measurement of the position always returns the eigenvalue  ). Hence, by the uncertainty principle, nothing is known about the momentum of such a state.

). Hence, by the uncertainty principle, nothing is known about the momentum of such a state.

Three dimensions

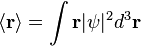

The generalisation to three dimensions is straightforward. The wavefunction is now  and the expectation value of the position is

and the expectation value of the position is

where the integral is taken over all space. The position operator is

Momentum space

In momentum space, the position operator in one dimension is

Formalism

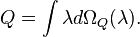

Consider, for example, the case of a spinless particle moving in one spatial dimension (i.e. in a line). The state space for such a particle is L2(R), the Hilbert space of complex-valued and square-integrable (with respect to the Lebesgue measure) functions on the real line. The position operator, Q, is then defined by:[2][3]

with domain

Since all continuous functions with compact support lie in D(Q), Q is densely defined. Q, being simply multiplication by x, is a self adjoint operator, thus satisfying the requirement of a quantum mechanical observable. Immediately from the definition we can deduce that the spectrum consists of the entire real line and that Q has purely continuous spectrum, therefore no discrete eigenvalues. The three-dimensional case is defined analogously. We shall keep the one-dimensional assumption in the following discussion.

Measurement

As with any quantum mechanical observable, in order to discuss measurement, we need to calculate the spectral resolution of Q:

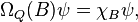

Since Q is just multiplication by x, its spectral resolution is simple. For a Borel subset B of the real line, let  denote the indicator function of B. We see that the projection-valued measure ΩQ is given by

denote the indicator function of B. We see that the projection-valued measure ΩQ is given by

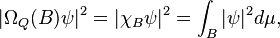

i.e. ΩQ is multiplication by the indicator function of B. Therefore, if the system is prepared in state ψ, then the probability of the measured position of the particle being in a Borel set B is

where μ is the Lebesgue measure. After the measurement, the wave function collapses to either

or

, where

, where  is the Hilbert space norm on L2(R).

is the Hilbert space norm on L2(R).

See also

References

- ↑ Atkins, P.W. (1974). Quanta: A handbook of concepts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855493-1.

- ↑ McMahon, D. (2006). Quantum Mechanics Demystified (2nd ed.). Mc Graw Hill. ISBN 0 07 145546 9.

- ↑ Peleg, Y.; Pnini, R.; Zaarur, E.; Hecht, E. (2010). Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0071623582.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||