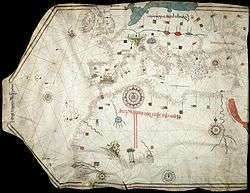

Portolan chart

Portolan or portulan charts are navigational maps based on compass directions and estimated distances observed by the pilots at sea. They were first made in the 13th century in Italy, and later in Spain and Portugal, with later 15th and 16th century charts noted for their cartographic accuracy.[1] With the advent of widespread competition among seagoing nations during the Age of Discovery, Portugal and Spain considered such maps to be state secrets. The English and Dutch relative newcomers found the description of Atlantic and Indian coastlines extremely valuable for their raiding, and later trading, ships. The word portolan comes from the Italian adjective portolano, meaning "related to ports or harbors", or "a collection of sailing directions".[1]

Portolan's rhumblines

Portolan maps all share the characteristic rhumbline networks, which emanate out from compass roses located at various points on the map. These better called "windrose lines" are generated by observation and the compass, and designate lines of bearing (though not to be confused with modern rhumblines and meridians).

To understand that those lines should be better called "windrose lines", one has to know that portolan maps are characterized by the lack of map projection, for cartometric investigation has revealed that no projection was used in portolans, and those straight lines they could be loxodromes only if the chart was drawn on a suitable projection.[2]

As leo Bagrow states:"..the word ("Rhumbline") is wrongly applied to the sea-charts of this period, since a loxodrome gives an accurate course only when the chart is drawn on a suitable projection. Cartometric investigation has revealed that no projection was used in the early charts, for which we therefore retain the name 'portolan'."[2]

Contents and themes

These charts, actually rough maps, were based on accounts by medieval Europeans who sailed the Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts. Such charts were later drafted for coastal resources in the Atlantic and Indian oceans. At the beginning of the Age of Discovery, charts had been made for the coast of Africa, Brazil, India, and past the Strait of Malacca into Japan, knowledge vital for the slow rise to prominence of the English Armada and of Dutch merchants, following in the wake of the Iberian powers. Frequently drawn on sheepskin vellum, portolan charts show coastal features and ports.[1] During that period, smaller ships could use more of the coastline as harbours than in the present era. They might need to seek refuge more often, and crews intentionally beached some ships for maintenance and repairs. Thus, mariners sought to learn of protected bays or flat beaches, not only for safe harbour but also for coastal navigation.

The straight lines shown criss-crossing many portolan charts represent the thirty-two directions (or headings) of the mariner's compass from a given point, with its principal lines oriented to the magnetic north pole.[1] Thus the grid lines varied slightly for charts produced in different eras, due to the natural changes of the Earth's magnetic declination.[1] These lines are similar to the compass rose displayed on later maps and charts. "All portolan charts have wind roses, though not necessarily complete with the full thirty-two points; the compass rose ... seems to have been a Catalan innovation."[3]

The portolan combined the exact notations of the text of the periplus or pilot book with the decorative illustrations of a medieval T and O map. In addition, the charts provided realistic depictions of shores. They were meant for practical use by mariners of the period. Portolans failed to take into account the curvature of the earth; as a result, they were not helpful as navigational tools for crossing the open ocean, being replaced by later Mercator projection charts.[1] Portolans were most useful in close quarters' identification of landmarks.[1] Portolani were also useful for navigation in smaller bodies of water, such as the Mediterranean, Black, or Red Seas.

History

The oldest extant portolan is the Carta Pisana, dating from approximately 1296 and the oldest preserved Majorcan Portolan chart is the one made by Angelino Dulcert who produced a portolan in 1339. This led towards two families of Portolan charts: the ones that are purely nautical and those that are nautical and geographical (with information and details of the inland). The Catalan portolan charts are of this second type, being usually made in Majorca.

Classification by origin

By its origin, Catow distinguishes three families of Portolan charts: Italian, developed mainly in Genoa, Venice and Rome; Catalan, with Palma de Mallorca as a main center of production; and Portuguese derived from the Catalan tradition.[4] (arab portolans added..)

Italian

The copious number of Italian Portolan charts begins in mid-s.XIII, with the oldest called Carta Pisana, which is kept in the National Library in Paris. The next century belong the Carignano Chart, disappeared from the National Archive of Florence where has been conserved for a long time; cartographic work of the Genoese Pietro Vesconte, the illustrator of the work of Marino Sanudo; the chart of Francisco Pizigano (1373), with stylistic influence from Mallorca; and those of Beccario, Canepa and the brothers Benincasa, natives of Ancona.

Catalan

They introduced a novelty in the nautical cartography for they are geographical maps, all with common stylistic representation of certain accidents and geographical areas. The masterpiece of the Majorcan Portolan charts is the Catalan Atlas made by Abraham Cresques in 1375, and kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

Abraham Cresques was a Majorcan Jew who worked at the service of Pedro IV of Aragon. In his "buxolarum" workshop was helped by his son Jafuda. The Atlas is a World Map, that is, world map and regions of the Earth with the various peoples who live there. The work was done at the request of Prince John, son of Pedro IV, desirous of a faithful representation the world from west to east. 12 sheets form the world map on tables, linked to each other by scroll and screen layout. Each table mesures 69 by 49 cm. The first four texts are filled with geographical and astronomical tables and calendars. The newest of the of Cresques World Map is the representation of Asia, from the Caspian sea to Cathay (China), which takes into account information from Marco Polo, and Jordanus .

In the s.XIV also highlights the work of Guillem Soler, which cultivates both styles, the purely nautical and nautical-geographical. To he s.XV corresponds the famous portolan chart from Gabriel Vallseca, (1439), kept in the Maritime Museum of Barcelona, notable for its delicacy of execution and lively picturesque details, masked by a spot of coffee left by Frédéric Chopin and George Sand.

Portuguese

The Portuguese Portolans, as it is known, come from the Majorcan tradition,[5] and although Portolan charts did not fulfill the requirements demanded by the expansion of the geographic horizons attained by Portuguese and Spaniards, they superposed the astronomical lines of the equator and tropics on top of the "winds spider", and they continued being elaborated until the s.XVI and the s.XVII.

The majorcan origin it's proven by Julio Rey Pastor who says in his book.... It's unforgivable, that some scholars, (those that are agains the majorcan origin) dear to wrote on the subject without reading João de Barros, which clearly states: "..mándou vir da ilha de Mallorca um mestre Jacome, hornera mui douto na arte de navegar, que fasia e instrumentos náuticos e que Ihe custou muito pelo trazer a este reino para ensinar sua sciencia aos officiaes portuguezes d'aquella mester.."[6]

Arab

Three medieval Portolan charts written in Arabic are preserved:[7]

- Map of Ahmed ibn Suleiman al-Tangi from 1413 to 1414.

- Map of Ibrahim al-Tabib al-Mursi from 1461

- Map of western Europe, anonymous and undated, preserved in the Ambrosiana Library, dating from early estimates s.XIV [8] or XV.

In addition there is a detailed description of a nautical Arab map of the Mediterranean in the Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Ibn Fadl Allah al-'Umari, written between 1330 and 1348.[7] There are also descriptions limited to smaller geographic regions, in a work of Ibn Sa'id al Maghribi (s.XIII ) and even in the work of Al-Idrisi ( s.XII ).[8]

See also

- Rhumbline network

- Catalan Atlas, 1375

- Catalan chart

- Catalan cartography

- Pietro Vesconte

- La Cartografía Mallorquina

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rehmeyer, Julie. The Mapmaker's Mystery, Discover, June 2014, pp. 44–49 (subscription).

- 1 2 Leo Bagrow (2010). History of Cartography. Transaction Publishers. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-1-4128-2518-4.

- ↑ Tony Campbell, "Portolan Charts from the Late Thirteenth Century to 1500", Chapter 19 of The History of Cartography, Volume I. U. of Chicago Press, 74th edition (May 15, 1987), p. 395.

- ↑ Catow: Die Geschichte der Kartographie / "History of Cartography", Berlin

- ↑ Estudos de História, Volume III. UC Biblioteca Geral 1. pp. 10–. GGKEY:7186FCQBHS5.

- ↑ Bibliografia Henriquina, Vol. I. UC Biblioteca Geral 1. pp. 2–. GGKEY:PGJ4UJDUYAZ.

- 1 2 Ducène (2013-06-01). "Le portulan décrit pair Arabic Al-'Umari" (PDF). Monde des Cartes (216): 81–90.

- 1 2 Vernet Ginés, John (1962). "The Maghreb in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana Chart" 16: 1–16.

Further reading

- Francesco Maria Levanto, Prima Parte dello Specchio del Mare, Genova, G.Marino e B.Celle, 1664. Disponibile anche in ristampa anastatica dell'edizione originale, Galatina, Congedo, 2002. (Italian)

- Konrad Kretschmer, Die italianischen Portolane des Mittelalters, Ein Beitrage zur Geschichte der Kartographie und Nautik, Berlin, Veroffentlichungen des Institut fur Meereskunde und des Geographischen Instituts an der Universitat Berlin, Vol. 13, 1909. (German)

- Bacchisio Raimondo Motzo, Il Compasso da Navigare, Opera italiana della metà del secolo XIII, Cagliari, Annali della facoltà di lettere e filosofia dell'Università di Cagliari, VIII, 1947. (Italian)

- Patrick Gautier Dalché, Carte marine et portulan au XIIe siècle. Le Liber de existencia rivieriarum et forma maris nostri Mediterranei, Pise, circa 1200, Roma, École Française de Rome, 1995. (French)

- Tony Campbell, "Portolan Charts from the Late Thirteenth Century to 1500", Chapter 19 of The History of Cartography, Volume I. U. of Chicago Press, 74th edition (May 15, 1987).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portolan charts. |

- Portolan Charts mini-site, University of Minnesota

- Portolan Charts, Samples of portolan charts illustrating the harbors and trade routes of the Mediterranean, 14th–16th centuries, from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

- Portolan charts from S.XIII to S.XVI - Additions, Corrections, Updates

- J. Rey Pastor & E. Garcia Camarero La cartografía mallorquina (Spanish)

- Portolan Charts butronmaker

- BigThink: Portolan Charts 'Too Accurate' to be Medieval